Aage Bohr | |

|---|---|

Bohr in 1955 | |

| Born | 19 June 1922 Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Died | 8 September 2009 (aged 87) Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Alma mater | University of Copenhagen |

| Known for | Geometry of atomic nuclei |

| Parent(s) | Niels Bohr, Margrethe Nørlund |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Nuclear physics |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Rotational States of Atomic Nuclei (1954) |

Aage Niels Bohr (Danish: [ˈɔːwə ˈne̝ls ˈpoɐ̯ˀ] ⓘ; 19 June 1922 – 8 September 2009) was a Danish nuclear physicist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1975 with Ben Roy Mottelson and James Rainwater "for the discovery of the connection between collective motion and particle motion in atomic nuclei and the development of the theory of the structure of the atomic nucleus based on this connection".[1] His father was Niels Bohr.

Starting from Rainwater's concept of an irregular-shaped liquid drop model of the nucleus, Bohr and Mottelson developed a detailed theory that was in close agreement with experiments.

Since his father, Niels Bohr, had won the prize in 1922, he and his father are one of the six pairs of fathers and sons who have both won the Nobel Prize and one of the four pairs who have both won the Nobel Prize in Physics.[2][3]

Early life and education

Bohr was born in Copenhagen on 19 June 1922, the fourth of six sons of the physicist Niels Bohr and his wife Margrethe Bohr (née Nørlund).[4] His oldest brother, Christian, died in a boating accident in 1934,[5] and his youngest, Harald, was severely disabled and placed away from the home in Copenhagen at the age of four.[6] He would later die from childhood meningitis.[7] Of the others, Hans became a physician; Erik, a chemical engineer; and Ernest, a lawyer and Olympic athlete who played field hockey for Denmark at the 1948 Summer Olympics in London.[8][9] The family lived at the Institute of Theoretical Physics at the University of Copenhagen, now known as the Niels Bohr Institute, where he grew up surrounded by physicists who were working with his father, such as Hans Kramers, Oskar Klein, Yoshio Nishina, Wolfgang Pauli and Werner Heisenberg.[4] In 1932, the family moved to the Carlsberg Æresbolig, a mansion donated by Carl Jacobsen, the heir to Carlsberg breweries, to be used as an honorary residence by the Dane who had made the most prominent contribution to science, literature, or the arts.[10]

Bohr went to high school at Sortedam Gymnasium in Copenhagen. In 1940, shortly after the German occupation of Denmark in April, he entered the University of Copenhagen, where he studied physics. He assisted his father, helping draft correspondence and articles related to epistemology and physics.[4] In September 1943, word reached his family that the Nazis considered them to be Jewish, because Bohr's grandmother, Ellen Adler Bohr, had been Jewish, and that they therefore were in danger of being arrested. The Danish resistance helped the family escape by sea to Sweden.[11] Bohr arrived there in October 1943, and then flew to Britain on a de Havilland Mosquito operated by British Overseas Airways Corporation. The Mosquitoes were unarmed high-speed bomber aircraft that had been converted to carry small, valuable cargoes or important passengers. By flying at high speed and high altitude, they could cross German-occupied Norway, and yet avoid German fighters. Bohr, equipped with parachute, flying suit and oxygen mask, spent the three-hour flight lying on a mattress in the aircraft's bomb bay.[12]

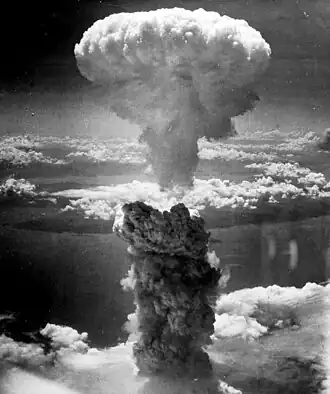

On arrival in London, Bohr rejoined his father, who had flown to Britain the week before.[12] He officially became a junior researcher at the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, but actually served as personal assistant and secretary to his father. The two worked on Tube Alloys, the British atomic bomb project. On 30 December 1943, they made the first of a number of visits to the United States, where his father was a consultant to the Manhattan Project.[13] Due to his father's fame, they were given false names; Bohr became James Baker, and his father, Nicholas Baker.[14] In 1945, the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, J. Robert Oppenheimer, asked them to review the design of the modulated neutron initiator. They reported that it would work. That they had reached this conclusion put Enrico Fermi's concerns about the viability of the design to rest.[14] The initiators performed flawlessly in the bombs used in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.[15]

Career

In August 1945, with the war ended, Bohr returned to Denmark, where he resumed his university education, graduating with a master's degree in 1946, with a thesis concerned with some aspects of atomic stopping power problems.[4] In early 1948, Bohr became a member of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey.[16] While paying a visit to Columbia University, he met Isidor Isaac Rabi, who sparked in him an interest in recent discoveries related to the hyperfine structure of deuterium. This led to Bohr becoming a visiting fellow at Columbia from January 1949 to August 1950.[4][17] While in the United States, Bohr married Marietta Soffer on 11 March 1950. They had three children: Vilhelm, Tomas and Margrethe.[17][18]

By the late 1940s it was known that the properties of atomic nuclei could not be explained by then-current models such as the liquid drop model developed by Niels Bohr amongst others. The shell model, developed in 1949 by Maria Goeppert Mayer and others, allowed some additional features to be explained, in particular the so-called magic numbers. However, there were also properties that could not be explained, including the non-spherical distribution of charge in certain nuclei.[19] In a 1950 paper, James Rainwater of Columbia University suggested a variant of the drop model of the nucleus that could explain a non-spherical charge distribution.[20] Rainwater's model postulated a nucleus like a balloon with balls inside that distort the surface as they move about. He discussed the idea with Bohr, who was visiting Columbia at the time, and had independently conceived the same idea, and had, about a month after Rainwater's submission, submitted for publication a paper that discussed the same problem, but along more general lines. Bohr imagined a rotating, irregular-shaped nucleus with a form of surface tension.[21] Bohr developed the idea further, in 1951 publishing a paper that comprehensively treated the relationship between oscillations of the surface of the nucleus and the movement of the individual nucleons.[22]

Upon his return to Copenhagen in 1950, Bohr began working with Ben Roy Mottelson to compare the theoretical work with experimental data. In three papers, that were published in 1952 and 1953, Bohr and Mottelson demonstrated close agreement between theory and experiment; for example, showing that the energy levels of certain nuclei could be described by a rotation spectrum.[23][24][25] They were thereby able to reconcile the shell model with Rainwater's concept.[21] This work stimulated many new theoretical and experimental studies.[19] Bohr, Mottelson and Rainwater were jointly awarded the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physics "for the discovery of the connection between collective motion and particle motion in atomic nuclei and the development of the theory of the structure of the atomic nucleus based on this connection".[1] Because his father had been awarded the prize in 1922, Bohr became one of only four pairs of fathers and sons to win the Nobel Prize in Physics.[26]

Only after doing his Nobel Prize-winning research did Bohr receive his doctorate from the University of Copenhagen, in 1954, writing his thesis on "Rotational States of Atomic Nuclei".[27] Bohr became a professor at the University of Copenhagen in 1956, and, following his father's death in 1962, succeeded him as director of the Niels Bohr Institute, a position he held until 1970. He remained active there until he retired in 1992.[28] He was also a member of the board of the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics from its inception in 1957, and was its director from 1975 to 1981.[29] In addition to the Nobel Prize, he won the Dannie Heineman Prize for Mathematical Physics in 1960, the Atoms for Peace Award in 1969, H. C. Ørsted Medal in 1970, Rutherford Medal and Prize in 1972, John Price Wetherill Medal in 1974, and the Ole Rømer medal in 1976.[16][30][31] Bohr and Mottelson continued to work together, publishing a two-volume monograph, Nuclear Structure. The first volume, Single-Particle Motion, appeared in 1969; the second, Nuclear Deformations, in 1975.[4]

In 1972 Bohr was awarded an honorary degree, doctor philos. honoris causa, at the Norwegian Institute of Technology, later part of Norwegian University of Science and Technology.[32] He was a member of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters from 1980.[33] Bohr was also an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences,[34] the American Philosophical Society,[35] and the United States National Academy of Sciences.[36]

In 1981, Bohr became a founding member of the World Cultural Council.[37]

Bohr's wife Marietta died on 2 October 1978.[18] In 1981, he married Bente Scharff Meyer (1926–2011).[38] His son, Tomas Bohr, is a professor of physics at the Technical University of Denmark, working in the area of fluid dynamics.[39] Aage Bohr died in Copenhagen on 9 September 2009.[28] He was survived by his second wife and children.[38]

Bohr's Nobel Prize medal was sold at auction in November 2011. It was subsequently sold at auction in April 2019 for $90,000.[40]

Notes

- 1 2 "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1975". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ "Nobel Prize FAQ". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ↑ "Facts on the Nobel Prize in Physics". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Aage N. Bohr – Biographical". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Stuewer 1985, p. 204.

- ↑ "Udstilling om Brejnings historie hitter i Vejle". ugeavisen.dk (in Danish). 11 April 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ↑ Pais 1991, pp. 226, 249.

- ↑ "Niels Bohr – Biography". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ Evans, Hilary; Gjerde, Arild; Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill; et al. "Ernest Bohr". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Pais 1991, pp. 322–333.

- ↑ Rhodes 1986, pp. 483–484.

- 1 2 Jones 1985, p. 280.

- ↑ Gowing 1964, pp. 248–249.

- 1 2 Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 95.

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 264–265, 308–309, 390–397.

- 1 2 "Bohr, Aage Niels". Institute for Advanced Study. Archived from the original on 7 January 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- 1 2 Chang, Kenneth (10 September 2009). "Aage Bohr, Physicist's Son Who Won Nobel, Dies at 87". The New York Times.

- 1 2 "Marietta Bohr (Soffer) (1922–1978)". Geni.com. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- 1 2 Bohr, Aage (11 December 1975). "Rotational Motion in Nuclei Nobel Lecture" (PDF). Copenhagen: The Niels Bohr Institute and Nordita. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ Rainwater, James (August 1950). "Nuclear Energy Level Argument for a Spheroidal Nuclear Model". Physical Review. American Physical Society. 79 (3): 432–434. Bibcode:1950PhRv...79..432R. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.79.432.

- 1 2 Lewin, Roger; Sherwood, Martin; Walgate, Robert (23 October 1975). "Nobel Prizes 1975: Medicine, Chemistry and Physics … and fifty years ago". New Scientist. 68 (972). ISSN 0262-4079.

- ↑ Bohr, Aage (January 1951). "On the Quantization of Angular Momenta in Heavy Nuclei". Physical Review. American Physical Society. 81 (1): 134–138. Bibcode:1951PhRv...81..134B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.81.134.

- ↑ Bohr, Aage; Mottelson, Ben R. (1953). "Collective and Individual-Particle Aspects of Nuclear Structure" (PDF). Matematisk-fysiske Meddelelser, Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. 27 (16). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ↑ Bohr, Aage; Mottelson, Ben R. (January 1953). "Interpretation of Isomeric Transitions of Electric Quadrupole Type". Physical Review. American Physical Society. 89 (1): 316–317. Bibcode:1953PhRv...89..316B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.89.316.

- ↑ Bohr, Aage; Mottelson, Ben R. (May 1953). "Rotational States in Even-Even Nuclei". Physical Review. American Physical Society. 90 (4): 717–719. Bibcode:1953PhRv...90..717B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.90.717.2.

- ↑ "Facts on the Nobel Prizes in Physics". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 12 May 2015. The others: William Henry Bragg (1915) and William Lawrence Bragg (1915); J. J. Thomson (1906) and George Paget Thomson (1937); and Manne Siegbahn (1924) and Kai M. Siegbahn (1981). Two pairs of fathers and sons have won Nobel Prizes in other fields: Hans von Euler-Chelpin (chemistry, 1929) and Ulf von Euler (medicine, 1970); and Arthur Kornberg (medicine, 1969) and Roger D. Kornberg (chemistry, 2006).

- ↑ "Rotational States of Atomic Nuclei". Columbia University. 1954. OCLC 04312983. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- 1 2 Anderson, Morten Garly (10 September 2009). "Nobelprisvinderen Aage Bohr er død ("Nobel Prize winner Aage Bohr has died")". Viden (in Danish). Archived from the original on 13 September 2009.

- ↑ "Nobel Laureate Aage Bohr has died". Niels Bohr Institute. 10 September 2009. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ Zichichi, Antonino. "Aage Bohr". Pontifical Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ↑ "Rutherford medal recipients". Institute of Physics. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ "Honorary doctors at NTNU". Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

- ↑ "Utenlandske medlemmer" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ↑ "Aage Niels Bohr". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ↑ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ↑ "Aage Bohr". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ↑ "About Us". World Cultural Council. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- 1 2 Close, Frank (14 September 2009). "Aage Bohr". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ↑ "Tomas Bohr". Technical University of Denmark. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ "Nobel Prize in Physics Awarded To Aage Niels Bohr 1975 UNC". Numis Bids. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

References

- Gowing, Margaret (1964). Britain and Atomic Energy, 1935–1945. London: Macmillan Publishing. OCLC 3195209.

- Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A.; Westfall, Catherine L. (1993). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44132-3. OCLC 26764320.

- Jones, R. V. (1985). "Meetings in Wartime and After". In French, A. P.; Kennedy, P. J. (eds.). Niels Bohr: A Centenary Volume. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 278–287. ISBN 978-0-674-62415-3.

- Pais, Abraham (1991). Niels Bohr's Times, In Physics, Philosophy and Polity. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852049-8.

- Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-44133-3.

- Stuewer, Roger H. (1985). "Niels Bohr and Nuclear Physics". In French, A. P.; Kennedy, P. J. (eds.). Niels Bohr: A Centenary Volume. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 197–220. ISBN 978-0-674-62415-3.

External links

- Aage Bohr on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture, 11 December 1975 Rotational Motion in Nuclei

- Oral History interview transcript with Aage Bohr 23 & 30 January 1963, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives