| Tsodilo | |

|---|---|

Rock art at Tsodilo | |

| Location | Ngamiland District, Botswana |

| Coordinates | 18°45′0″S 21°44′0″E / 18.75000°S 21.73333°E |

| Official name | Tsodilo |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, iv |

| Designated | 2001 (25th session) |

| Reference no. | 1021 |

| Region | List of World Heritage Sites in Africa |

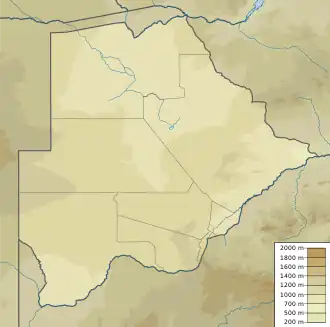

Tsodilo Hills  Tsodilo (Africa) | |

The Tsodilo Hills (Tswana: Lefelo la Tsodilo) are a UNESCO World Heritage Site (WHS), consisting of rock art, rock shelters, depressions, and caves in southern Africa. It gained its WHS listing in 2001 because of its unique religious and spiritual significance to local peoples, as well as its unique record of human settlement over many millennia. UNESCO estimates there are over 4500 rock paintings at the site.[1] The site consists of a few main hills known as the Child Hill, Female Hill, and Male Hill.[2]

Geography

There are four chief hills. The highest is 1,400 metres AMSL, one of the highest points in Botswana. The four hills are commonly described as the "Male" (the highest), "Female", "Child", plus an unnamed knoll.[2] They are about 40 km from Shakawe and can be reached via a good graded dirt road.

There is a managed campsite between the two largest hills, with showers and toilets. It is near the most famous of the San paintings at the site, the Laurens van der Post panel, after the South-African writer who first described the paintings in his 1958 book 'The Lost World of the Kalahari'. There is a small museum and an airstrip near the campsite.

Archaeology

People have used the Tsodilo Hills for painting and ritual for thousands of years. UNESCO estimates that the hills contain 500 individual sites representing thousands of years of human habitation. The hills' rock art has been linked to the local hunter gatherers. It is believed that ancestors of the San created some of the paintings at Tsodilo, and were also the ones to inhabit the caves and rock shelters. There is evidence that Bantu peoples were responsible for some of the artworks at the hills.[3] Some of the paintings have been dated to be as early as 24,000 years before present.[4]

Rhino Cave

Rhino Cave is located at the North end of the Female Hill and has two main walls where paintings are located. The White Rhino painting (for which the cave is named) is located on the north wall, and is split by another painting of a Giraffe.[3] Excavations of the cave floor turned up many lithic materials. This cave lacks ostrich egg shell, bone artifacts, pottery or iron, but there were a few mongongo shell fragments found in Later Stone Age layers.[3]

Charcoal found during excavations has been dated to the African Iron Age, the Later Stone Age (LSA), and the Middle Stone Age (MSA). Mostly stone artifacts from the LSA were made from local materials such as quartz and jasper.[3] MSA artifacts from the cave are mostly prepared projectile points. The points are typically found in various stages of production, some abandoned and some finished.[3]

The paintings of Rhino Cave are mostly located on the North wall, and have been painted in red or red-orange pigment, excepting the rhino which was painted in white. Around the rhino and the giraffe are various paintings, mostly in red, of geometrics.[3] On the opposite wall, the cave is host to grooves and depressions that have been ground into the rock. They may have been created using hammer stones or grindstones from the LSA period, which have been found at Tsodilo.[3]

White Paintings

The white colored rock art at Tsodilo is associated with Bantu peoples.[3] Many of the white paintings are located in the aptly named White Paintings Rock Shelter, located on the Male Hill.[5] (There are red paintings in this shelter, as well.) The white paintings depict animals, both domestic and wild, as well as human like figures.[5] The human figures are usually painted with their hands on their hips. A handful of them are on horseback, suggesting that these were painted no earlier than the mid-1800s, when horses were first introduced to the area.[5]

Dates taken from charcoal, ostrich egg shell, bone samples and the deposits ranged from the MSA to LSA.[5] (There is also evidence that the site was used during the historical period: a nylon button and European glass beads were found in the top layers of excavations at the site.[5]) LSA layers included hammer stones and grindstones, along with bone artifacts and mircolithics. Pottery sherds, ostrich egg shell beads, and mongongo shells were also uncovered.[5] MSA deposits included stone blades as well as other lithic tools.

Red Paintings

The Tsodilo Hills have a myriad of red rock art; it can be found all over the site. In Rhino Cave, some of the red paintings seem to be older than the white rhino. Red paintings here, and around Tsodilo, are attributed to the San people.[3]

Depression Rock Shelter Site

Located on the northwest side of the Female Hill, this site gets its name from the depressions that have been ground into the shelter walls. Accompanying these marks are red paintings of what appear to be cattle, as well as geometrics.[6] The rock shelter site, dated from charcoal samples, had its earliest occupation at least 30,000 years ago.[6] Excavations dug up LSA stone tools and Iron Age artifacts. Pottery found in the deepest layers was dated to the first century, and is affiliated with the oldest stone artifacts found in this area.[6] Mongongo nut shells were also uncovered in the various deposits, including the deepest layers, which makes them the oldest mongongo nuts ever found in archaeological context.[6]

Metallurgy

The Tsodilo Hills are made up of a number archaeological sites. Two of these sites, known as Divuyu and Nqoma, have evidence of Early Iron Age metal artifacts [7] Excavated from the two sites contained fragments of jewelry and metal tools, all made from iron and/or copper. Jewelry pieces were from bangles, beads, chains, earrings, rings, and pendants, while tools included chisels, projectiles and arrow heads, and even blades.[7] These two sites share similar fabrication technology, but have different styles of metal working. Slag and tuyères seem to indicate that Divuyu and Nqoma may have been iron smelting areas, making them one of the few Early Iron Age sites in southern Africa with evidence of metal working.[7]

Cultural significance

These hills are of great cultural and spiritual significance to the San peoples of the Kalahari. They believe the hills are a resting place for the spirits of the deceased and that these spirits will cause misfortune and bad luck if anyone hunts or causes death near the hills. Tsodilo is also an object of debate regarding how the San once lived.[8]

Oral Traditions

Many local peoples around the Tsodilo Hills have stories of times past that deal with the many painted caves and rock shelters at the site. Oral traditions often tell of the Zhu people, a local San group, using rock shelters for protection from the elements or as ritual areas.[5]

One tale claims that hunters would come into the rock shelters to contact ancestors if a hunt was unsuccessful. They would then ask for a good hunt the next time they went out.[9] In thanks, when the hunt was successful, the people would return to the shelter and cook for their ancestors. In some of these alleged campsites, there is little to no evidence of fire remains.[9]

Still, there are areas where rituals, such as rain making prayers, are performed. Older people in the area can still remember using some rock shelters as campsites when they were children. The Whites Paintings rock shelter may have been used as a camp during the rainy season as early as 70 – 80 years ago.[5]

The local San people believe Tsodilo is the birthplace of all life, art there made by the descendants of the first people. Tsodilo's geography, trails and grooves in the earth are known as the trails and footprints of the first animals, making their way to the first watering hole [10]). A natural water spring at Tsodilo, near the Female Hill, is used as both a water collection site and a ritual site. It is seen as sacred, and used by countless peoples to cleanse, heal, and protect.[10]

Claim of earliest known ritual

In 2006 the site known as Rhino Cave became prominent in the media when Sheila Coulson of the University of Oslo stated that 70,000-year-old artifacts and a rock resembling a python's head representing the first known human rituals had been discovered. She also backed her interpretation of the site as a place of ritual based on other animals portrayed: "In the cave, we find only the San people's three most important animals: the python, the elephant, and the giraffe.[11] Since then some of the archaeologists involved in the original investigations of the site in 1995 and 1996 have challenged these interpretations. They point out that the indentations (known by archaeologists as cupules) described by Coulson do not necessarily all date to the same period and that "many of the depressions are very fresh while others are covered by a heavy patina." Other sites nearby (over 20) also have depressions and do not represent animals. The Middle Stone Age radiocarbon and thermoluminescence dating for this site does not support the 70,000 year figure, suggesting much more recent dates.

Discussing the painting, the archaeologists say that the painting described as an elephant is actually a rhino, that the red painting of a giraffe is no older than 400 AD and that the white painting of the rhino is more recent, and that experts in rock art believe the red and white paintings are by different groups. They refer to Coulson's interpretation as a projection of modern beliefs on to the past and call Coulson's interpretation a composite story that is "flatout misleading". They respond to Coulson's statement that these are the only paintings in the cave by saying that she has ignored red geometric paintings found on the cave wall.

They also discuss the burned Middle Stone Age points, saying that there is nothing unusual in using nonlocal materials. They dismiss the claim that no ordinary tools were found at the site, noting that the many scrapers that are found are ordinary tools and that there is evidence of tool making at the site. Discussing the 'secret chamber', they point to the lack of evidence for San shamans using chambers in caves or for this one to have been used in such a way.[12]

Notes

- ↑ Thebe, Phenyo. "Intangible Heritage at Tsodilo Hills".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Staurset, Sigrid. "Ritualized Behavior in the Middle Stone Age: Evidence from Rhino Cave, Tsodilo Hills, Botswana".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Robbins, Lawrence; Murphy, Michael; Campbell, Alec; Brook, George (1996). "Excavations at the Tsodilo Hills Rhino Cave". Botswana Notes and Records. 28: 23–45. JSTOR 40980131.

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan. 2008

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Robbins, L.H.; Murphy, M.L.; Brook, G.A.; Ivester, A.H.; Campbell, A.C; Klein, R.G.; Milo, R.G.; Stewart, K.M.; Downey, W.S.; Stevens, N.J. (2000). "Archaeology, Palaeoenvironment, and Chronology of the Tsodilo Hills White Paintings Rock Shelter, Northwest Kalahari Deser, Botswana". Journal of Archaeological Science. 27 (11): 1085–1113. doi:10.1006/jasc.2000.0597.

- 1 2 3 4 Robbins, L.H.; Campbell, A.C. (1989). "The Depression Rock Shelter Site, Tsodilo Hills". Botswana Notes and Records: 1–3.

- 1 2 3 Miller, Duncan; van der Merwe, Nikolaas (1994). "Early Iron Age Metal Working at the Tsodilo Hills, Northwestern Botswana". Journal of Archaeological Science. 21: 101–115. doi:10.1006/jasc.1994.1011.

- ↑ Sadr, Karim (1997). "Kalahari archaeology and the Bushman debate". Current Anthropology. 38 (1): 104–112. doi:10.1086/204590. JSTOR 2744444. S2CID 144203689.

- 1 2 Campbell, A.C.; Robbins, L.H.; Murphy, M.L. (1994). "Oral Traditions and Archaeology of the Tsodilo Hills Male Hill Cave". Botswana Notes and Records. 26: 37–54. JSTOR 40959180.

- 1 2 Segadika, Phillip (2006). "Managing Intangible Heritage at Tsodilo". Museum International. 58 (1–2): 31–40. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0033.2006.00548.x. S2CID 54755278.

- ↑ "World's Oldest Ritual Discovered -- Worshipped The Python 70,000 Years Ago". ScienceDaily.com.

- ↑ Robbins, Lawrence H.; AlecC. Campbell; George A. Brook; Michael L. Murphy (June 2007). "World's Oldest Ritual Site? The "Python Cave" at Tsodilo Hills World Heritage Site, Botswana" (PDF). NYAME AKUMA, the Bulletin of the Society of Africanist Archaeologists (67). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

References

- Ursula Erasmus (1992) Bushman Culture, published by Excalibur, 315 pp ISBN 1-85634-191-7

- C. Michael Hogan (2008) Makgadikgadi, The Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham

- Luis Pancorbo (2000) "Al fin las colinas de Tsodilo" en "Tiempo de África". pp. 280–286. Laertes, Barcelona. ISBN 84-7584-438-3

- Sheila Coulson, Sigrid Staurset, and Nick Walker (2011) "Ritualized Behavior in the Middle Stone Age: Evidence from Rhino Cave, Tsodilo Hills, Botswana" PaleoAnthropology 2011:18-61