| West Kill | |

|---|---|

West Kill from Shoemaker Road | |

Location of the mouth of the West Kill  West Kill (the United States) | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| Region | Catskills |

| County | Greene |

| Towns | Hunter, Lexington |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | W slope of Hunter Mountain |

| • coordinates | 42°10′24″N 74°14′15″W / 42.17333°N 74.23750°W[1] |

| • elevation | 3,100 ft (940 m) |

| Mouth | Schoharie Creek |

• location | Lexington, New York |

• coordinates | 42°14′45″N 74°22′36″W / 42.24583°N 74.37667°W[1] |

• elevation | 1,299 ft (396 m) |

| Length | 11 mi (18 km), E-W |

| Basin size | 31.2 sq mi (81 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | E of Spruceton |

| • average | 10.1 cu ft/s (0.29 m3/s) |

| • minimum | .45 cu ft/s (0.013 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 4,320 cu ft/s (122 m3/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | N of West Kill |

| • average | 41.7 cu ft/s (1.18 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 1.3 cu ft/s (0.037 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 19,100 cu ft/s (540 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Progression | West Kill → Schoharie Creek → Mohawk River → Hudson River → Upper New York Bay |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Pettit Brook, Styles Brook, Hagadone Brook, Bennett Brook, Newton Brook, Beech Ridge Brook, Roarback Brook |

| • right | Hunter Brook, Herdman Brook, Schoolhouse Brook |

| Waterfalls | Diamond Notch Falls |

The West Kill, an 11-mile-long (18 km)[2] tributary of Schoharie Creek, flows through the town of Lexington, New York, United States, from its source on Hunter Mountain, the second-highest peak of the Catskill Mountains.[3] Ultimately its waters reach the Hudson River via the Mohawk. Since it drains into the Schoharie upstream of Schoharie Reservoir, it is part of the New York City water supply system. It lends its name to both a mountain to its south and a small town midway along its length.

The West Kill's 31.2-square-mile (81 km2)[4] watershed accounts for 10 percent of the reservoir's basin. It has the highest elevations[5] and steepest slopes[6] of any of the Schoharie's subwatersheds, with runoff from seven of the 35 Catskill High Peaks draining into the stream. Due to limited development and extensive land protection in the stream's watershed, its water is relatively clean, supporting a habitat for both wild and stocked trout; historically it has drawn fly fishers and other anglers. However, the West Kill has contributed to turbidity issues with the Schoharie creek and reservoir due to recent floods; several government agencies have worked together to develop a management plan that will mitigate the floods and the turbidity.

Course

The upper 8 miles (13 km) of the West Kill flows west through the Spruceton Valley to the hamlet of West Kill. From there it turns to a more northerly course to the Schoharie at Lexington.

Spruceton Valley

Two streams that later join rise in the cirque between Hunter and Southwest Hunter mountains, amidst the dense forests of the West Kill Wilderness Area, part of the Catskill Park. The source of the northern stream is at 3,100 feet (940 m),[lower-alpha 1] the higher of the two. It flows through a narrow groove down the steep upper slopes of the cirque for its first quarter-mile (400 m).[7]

Just under 2,700 feet (820 m) in elevation, the terrain becomes gentler. At the town line between Hunter and Lexington, the two streams join.[7] The West Kill flows steadily downhill for its next half-mile (800 m) as the Devil's Path hiking trail, itself descending the mountain, gradually comes closer to the stream and follows it along its north side.[8]

At Diamond Notch Falls, the Devil's Path merges briefly with the Diamond Notch Trail coming in from the west. The two cross the West Kill on a wooden bridge, the uppermost crossing of the stream. Just south of the stream, the trails again diverge, with the Devil's Path following the stream for a short distance on that side before beginning its ascent of West Kill Mountain to the southwest. The Diamond Notch Trail runs parallel to the kill for another 0.7 miles (1.1 km) to the trailhead parking lot, the eastern end of Greene County Route 6, known locally as Spruceton Road, at 2,220 feet (680 m) elevation.[8]

Shortly after that, the valley begins to widen slightly. The West Kill receives its first tributary, an unnamed stream that flows into it from the slopes of the eponymous mountain to its south. West of that confluence the kill begins to pass some cleared areas and structures. As Spruceton Road bends to the north away from the stream, its first named tributary, Hunter Brook, flows in from the north just 500 feet (150 m) east of where Spruceton Road crosses. After receiving Pettit Brook from the south, Spruceton Road returns to the north side of West Kill.[9]

Privately owned Wolff Road crosses the West Kill 2,500 feet (760 m) beyond.[10] A half-mile further west, a short local street, Ad Van Road, crosses.[11] Just below, at the former hamlet of Spruceton, Herdman Brook flows into the West Kill from the slopes of Evergreen Mountain to the north.[12] Styles Brook follows shortly, draining the cirque below West Kill Mountain's summit, from the south, just west of where Baker Road crosses to provide access to several farms on that side. Cleared fields and structures are now found on both sides of the stream.[13]

Another 1,200 feet (370 m) further west, the kill again crosses under Spruceton Road.[12] The road and stream meander west another mile (1.6 km), never getting very far from each other, as the West Kill receives more unnamed tributaries from the mountains to the north and south.[14] Auffarth and Tumbleweed Ranch roads cross the kill along this stretch.[15]

After returning to the south side of Spruceton Road, the West Kill receives Hagadone Brook from the valley on its south, between the two ridges on the north face of North Dome. Schoolhouse Brook flows in from the north 1,500 feet (460 m) further west.[16] Shoemaker Road, providing access to several properties on the stream's south side, crosses 250 feet (76 m) east of where Bennett Brook flows in from the south.[17]

Long Road crosses over the West Kill 0.6 mile (1 km) downstream,[18] just above where Newton Brook flows down from a valley on the slopes of Mount Sherrill to the south. After following Spruceton Road closely for an equivalent distance, the stream crosses under it for the last time. As the West Kill reaches the similarly named hamlet, it descends under 1,500 feet (460 m) in elevation.[19]

Below West Kill hamlet

As the West Kill passes north of West Kill, at first flowing right behind some of the hamlet's houses, it begins to turn toward the northwest as it widens briefly through an area with several bars.[20] After the stream narrows again, it returns more to the west-northwest to flow under New York State Route 42. About 150 feet (46 m) beyond the bridge, it veers back to north-northeast, then north-northwest again, paralleling the highway. Through this stretch it receives three unnamed tributaries from the west, all rising from the slopes of the unnamed mountains northwest of Deep Notch.[19]

At a bend in the stream a mile (1.6 km) north of West Kill, where the Shandaken Tunnel's visible surface right-of-way, along with a power line, cross the kill twice, Beech Ridge Brook flows in from the west.[21] Immediately north of the bend, the West Kill crosses under Route 42, entering a section where both banks are shored up with riprap for the next 800 feet (240 m) as the stream and road again follow a north-northeasterly course. The natural banks return where Roarback Brook, the lowest tributary of the West Kill, flows in from slopes of Vly Mountain to the west.[22]

After a mile (1.6 km), the West Kill crosses under Route 42 for the last time just west of the hamlet of Lexington. Shortly afterwards, it turns east then slightly east-southeast to its mouth at Schoharie Creek. At this point it has descended to just above 1,300 feet (400 m) in elevation.[21]

Watershed

The West Kill's 31.2-square-mile (81 km2)[6] watershed, accounting for 10 percent of the total Schoharie Reservoir watershed,[23] is, like the stream itself, predominantly in the town of Lexington. Its eastern area, where the stream rises, is in Hunter, and some of the uppermost areas where its lower western tributaries arise are in another neighboring town, Halcott. Ridgelines between the mountains on either side form the watershed's boundaries except for the area around its mouth at Lexington.[6]

On the north side Rusk Mountain and the peaks to its west form the boundary between the West Kill watershed and the Schoharie's. South of the range from Southwest Hunter Mountain to Mount Sherrill drainage flows into Esopus Creek, another Hudson tributary in Ulster County. The unnamed peaks over 3,000 feet (910 m) in elevation between Halcott and Vly mountains on the southwestern boundary are part of the Catskill Divide, since the Vly Creek basin on the opposite side is part of the Delaware River watershed. On the northwest is the smaller watershed of the Little West Kill, another Schoharie tributary.[24]

The highest point in the West Kill watershed is the approximately 4,040-foot (1,230 m) summit of Hunter Mountain, also the highest point in the Schoharie and Mohawk watersheds. As a whole the watershed has the highest overall elevation of any subwatershed within the Schoharie basin.[5] It also boasts the steepest average slope, at 29 percent, with a drainage density of 0.0013 m/m2,[6] lower than average for the Catskills.[4]

Within the watershed, the predominant land use is open space. Almost two-thirds of the land,[25] 16,182 acres (65.49 km2), is deliberately undeveloped, much of it in forested lands on the mountains, most of which are protected area managed by the state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). Most of the watershed is within New York's Catskill Park, where the state constitution requires that land owned by the state be kept "forever wild" as part of New York's Forest Preserve.[26]

Most of the forest in the watershed is deciduous, accounting for nearly three-quarters of the watershed's total land cover. These woodlands are mostly the beech-birch-maple northern hardwood forest that covers much of the Catskills. The next largest amount is coniferous forest at 14 percent, most of it in the montane spruce-fir boreal forest that grows on the higher-elevation mountain summits and the ridges between them, with some remaining Eastern hemlock stands and reforested areas of Norway spruce also included. Mixed forests, including areas where the deciduous forest is transitioning to coniferous on mountain slopes, accounts for another 11 percent of cover, and grass in open fields is 2 percent of the total.[25]

Water covers 21 acres (8.5 ha);[25] the National Wetlands Inventory maintained by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has identified 79 separate wetlands within the West Kill watershed, totaling 128.7 acres (52.1 ha), including all open water. While the largest portion is the stream itself, about 54 percent of the total acreage is palustrine wetlands such as marshes and swamps.[27] Only 7 acres (2.8 ha) of the basin is covered with impervious surfaces like road pavement[25] (the watershed has a road density of 0.004 kilometres (0.0025 mi) of road per 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi) of land area).[6]

After open space, low-density and vacant residential use accounts for most of the remaining land in the watershed, at 33.3 percent. Agriculture, most of it the raising of livestock, accounts for 2.6 percent. Hotels come in at 0.7 percent.[25]

History

Before European colonization, it is possible that the Iroquois and other Native American peoples who lived in the Catskill region might have explored the West Kill valley. But there is no evidence that they did, and they did not settle in the mountains due to their low-quality farmland, preferring the richer soils closer to the rivers. If they did venture into the Catskills, it was to travel across them, hunt or practice religious rituals.[28]

Even when Europeans came, settlers did not go to the West Kill valley. It was surveyed, and lot lines were drawn up as part of the 1708 Hardenburgh Patent, the land grant that marks the formal beginning of European land ownership in the Catskills. There is no record of anyone living in the current boundaries of the town of Lexington before independence. Robert R. Livingston, whose family had traded shares of the patent and eventually came to own half of its two million acres (8,100 km2), leased one lot in the town in 1777, but it is not known whether the lessee chose to live there.[29]

The earliest known settler in Lexington was a man named Dryer, who used the West Kill's waterpower to operate a woolen factory in 1780. Some other settlers, the first inhabitants of the hamlet of West Kill, were also reported as having moved in around the same time. Others followed quickly, drawn by the promise of abundant furs and timber on land that was still cheap. In 1813 Lexington was separated from Woodstock into the present town.[29]

How much of this early growth took place along the West Kill is uncertain. In his 1813 gazetteer of the state as it was at the time, Horatio Gates Spafford (who described Lexington under Windham) describes the Schoharie and the Batavia Kill, which empties into it upstream from Lexington, as already supporting many rapidly-built mills. He does not mention the West Kill, which, while some other accounts also report similar milling operations along it, may also indeed have been comparatively undeveloped at that time.[30]: 18–19

Within a decade that changed. The Catskills became home to many small tanneries, who found the bark of the range's many stands of Eastern hemlock to be an excellent source of tannin. Hides from all over the Americas were shipped to Greene County to be tanned. In 1821 one tannery was opened on the West Kill at the site of today's hamlet, spurring that community's growth. It made up for its remote location with access to the stream's water and the vast supply of bark in the surrounding forests.[30]

Another tannery on the West Kill opened in 1830, about two miles (3.2 km) above the hamlet. The same year there was a schism among the Baptist congregation in Lexington over whether to replace their elderly pastor, and the dissenting group left to form their own church in West Kill. Three years later, a post office was established in the hamlet, showing how the upper West Kill valley had gained population in three decades.[30]: 20–21

By the mid-19th century, tanneries had begun to close as supplies of usable hemlock bark dwindled. In the years after the American Civil War, few were left, and the operators of the boarding houses built or converted from farmhouses to provide housing for tannery workers began reopening them as summer resorts. They promoted them as offering a quieter, more relaxed vacation experience than more popular, more accessible resorts like the Catskill Mountain House to the east.[30]: 26–27

In 1867, records showed several of these resorts existed, as far up the West Kill as Spruceton. Despite their economic success, during the latter half of the century the area's population declined, due not only to the loss of the tanning jobs but the difficulty of farming the land. Dairy farming had the most potential, but without a railroad in reach farmers could not get their products, even butter and cheese, to larger markets.[30]: 26–27

With that loss of population, the infrastructure along the West Kill was also neglected. Old millraces and dams were no longer recorded on maps, and the road up the valley went unmaintained past the Hunter town line since fewer people lived that far up the valley. Another road that had once provided an outlet for the valley other than through West Kill, to Peck Hollow past North Dome, also fell into disrepair.[30]: 26–27

Just before the end of the century, Article 14 of the 1894 state constitution, retained ever since, established the Forest Preserve, under which all state land in the Catskill Park (established in 1904) was to remain forever wild, constraining development in the West Kill watershed. The protection this provided the watershed led New York City to construct Schoharie Reservoir in the mid-1920s to supply its growing population. During the same time, the advent of the automobile gave Americans more control over where and how long they vacationed, leading many New Yorkers to go places other than the Catskills, while those who still came generally spent less time there. Some motels were built along the West Kill in the Spruceton Valley to capture this traffic, but farming began to play an even larger role in the area's economy.[30]: 28–29

This state of affairs changed slightly in the later 20th century. Hikers began regularly visiting Diamond Notch Falls and climbing the mountains (both with and without trails) around the valley. As some older farmers on the gentler northern slopes of the Spruceton Valley got out of the business, the former farms and some of the privately owned forests around them were subdivided to create large lots for weekend and summer residences[30]: 31–32 In 2017 West Kill Brewing, a microbrewery, was established near the head of the Spruceton Valley, using locally sourced yeast, thyme, maple syrup, and other ingredients along with the waters of the nearby streams.[31]

Geology

While the Catskills originated during the Devonian period, around 375 million years ago, as a former river delta uplifted and became a dissected plateau, the Spruceton Valley evinces the comparatively recent effects of the Wisconsin glaciation, which ended 12,000 years ago. Cirques, the U-shaped valleys including the one in which the West Kill rises, abound, and other mountain valleys from which the stream's tributaries descend were formed by alpine glaciers that remained as the large ice sheets retreated to the north in the face of the warming climate. Meltwater fed many streams, which eventually became today's West Kill.[5]

Most of the watershed's bedrock is the combination of shale, sandstone and siltstone that underlies the Catskills. The upper Spruceton Valley is underlain by rocks of the Lower Walton Formation; puddingstones and other conglomerates are found in the Upper Walton Formation at high elevations. From just above the hamlet of West Kill to its mouth, the West Kill flows over rocks of the Oneonta Formation.[5]

The superficial deposits within the watershed also reflect its glacial origins. While the high elevations are covered with rock, glacial till dominates further down, including in much of the West Kill's upper reaches. Alluvium begins to be seen about midway down the Spruceton Valley, with outwash visible as the stream bends towards the north at the hamlet of West Kill. Closer to Lexington and the stream's mouth there are some kame areas along the banks.[5]

Most of the eroded bedrock that has reached the West Kill's streambed is, in its upper reaches, imbricated, worn into small plate-shaped rocks that nest with each other in a scale-like pattern. There are also areas where the bedrock forms lateral and vertical grade controls, Diamond Notch Falls being the most prominent example. Areas of the streambed where bedrock is not exposed and no imbricated rocks have settled are generally covered in a fine red lacustrine silty clay.[5]

Hydrology

The West Kill's watershed receives an average 45.2 inches (1,150 mm) of precipitation annually, making it one of the wettest areas of the Catskills. Most of it is concentrated in seasonal events such as summer thunderstorms or remnants of hurricanes later in the year. Rain-on-snow events in springtime are another large contributor; the northern-facing slopes of West Kill, North Dome, Sherrill and the other mountains on the south side of the Spruceton Valley receive little direct sunlight during the year, thus retaining large areas of snowpack late into the spring.[4]

This pattern of precipitation, combined with the West Kill watershed's slopes, the steepest in the Schoharie Basin, and low drainage density, results in flashiness, as the stream and its tributaries rise and fall quickly in response to storm events. The forests that cover much of the watershed tend to mitigate this somewhat, but not so much on the north side of the valley since the limited sunlight makes for less dense vegetation.[4]

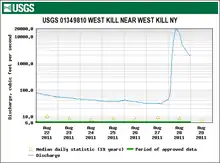

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) maintains two stream gauges along the West Kill. One, in operation since the 1950s but not reporting continuous data until 1997,[4] is located on the lower stream, roughly 1.4 miles (2.3 km) north of the hamlet of West Kill, just downstream from the Beech Ridge Brook confluence.[32] The other, established in 1997 and reporting continuously since then, is located near the kill's headwaters, at the last crossing of Spruceton Road, just below the Hunter Brook confluence.[33]

In 2016, the lower gauge reported an average discharge of 41.7 cubic feet (1.18 m3) per second;[34] at Spruceton the mean flow was 10.1 cubic feet (0.29 m3) per second.[35] Both stations recorded their highest discharges ever on the same day: August 28, 2011, as Hurricane Irene passed through the area. At the West Kill station the stream was flowing at 19,100 cubic feet (540 m3) per second,[32][lower-alpha 2] and Spruceton's discharge was 4,320 cubic feet (122 m3).[33] Minimums for both stations are 1.3 cubic feet (0.037 m3)[32] and 0.45 cubic feet (0.013 m3)[33] per second respectively, with West Kill's low coming over a period of several days in August 2002[32] and Spruceton's on several occasions in September 1998 and October 1999.[33]

DEC rates the West Kill's water quality at Class C, suitable for fishing and non-contact human recreation. The agency also adds a "(TS)", indicating that the stream's waters are ideal for trout spawning.[36] The kill's waters are pure enough to be part of the New York City water supply system; after draining into the Schoharie they are impounded at Schoharie Reservoir downstream, where they can be delivered through the Shandaken Tunnel back under the hamlet of West Kill to Esopus Creek at Shandaken. From there they go to Ashokan Reservoir, which supplies 10 percent of the city's water, and then, via the Catskill Aqueduct, to customers, without requiring filtration.[26]

Water quality

Because of the West Kill's role in the city's water system, the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has monitored the stream's overall quality. That began in 1994 with a station one-eighth of a mile (201 m) above the stream's mouth; in 2002, a second station was established near the USGS stream gauge above Spruceton. Both have generally reported consistent high quality, better than the nearby subwatersheds of the East and Batavia kills.[23]

Metrics important to aquatic life habitat have remained above levels legally mandated or recommended. The West Kill has reported dissolved oxygen at 10 mg/L, safely above the 7 mg/L level DEC considers safe for trout spawning. Fecal coliform levels have never exceeded 10 CFU/100 ml, less than 5 percent of the state legal maximum to be considered safe for drinking. Phosphorus and sulfate levels are low, specific conductivity is also low, suggesting a low degree of chloride contamination,[lower-alpha 3] and the stream's overall pH has remained within the same 6.6–7.9 range as other streams in the upper Schoharie basin. The West Kill's water temperature is in a 6–10 °C (43–50 °F) annual range, reflecting the considerable shade provided by forest cover around its headwaters.[23]

However, the West Kill's turbidity levels, while not abnormal, have been seen as sufficiently high to contribute to turbidity problems downstream of its mouth at the reservoir. Readings have generally been around 2 Nephelometric Turbidity Units, which by itself is not a problem, but is similar to that of the Batavia Kill, a longer tributary with a more developed watershed that drains into the Schoharie downstream from the West Kill. This may be the result of disturbances to the streambed and the loss of riparian cover upstream; the lower stretches, particularly the channelized reach along Route 42, are showing signs of incision. More of the silts and clays on the streambed could thus be stirred up and become suspended sediment.[23]

Flood control

Before Hurricane Irene, which exceeded the 100-year flood levels as mapped by the Federal Emergency Management Agency's flood insurance rate map[37] and came close to 500-year levels,[38]: 32 [lower-alpha 4] there had been some major floods of the West Kill; a 1927 event that washed away every bridge in the valley and the flooding that followed the rapid melting of snow that fell in the January 1996 blizzard are often cited as notable past floods of the stream.[39] But since streamflow has only been regularly monitored since the 1990s, there is not enough data yet to make estimates of flood frequency below the 100-year level and thus map the West Kill's floodplain more accurately. In the mid-2000s, DEC began developing newer maps of the floodplains using aerial Lidar mapping;[27] they were finished in 2006.[40]: 13

In 2005, a combined effort of the Greene County Soil and Water Conservation District and the DEP resulted in a management plan for the West Kill. The stream was subdivided into 21 sections from where it leaves Forest Preserve land to its mouth and inventoried in great detail. Issues of concern for habitat and flood management were identified and recommendations made.[39]

The areas of greatest concern for flooding were the reach of the stream around the hamlet of West Kill and further downstream around the Beech Ridge Brook confluence. In both the stream channel widens, having shown considerable aggradation over the years, and floods have changed its course considerably in the past, leaving wide bars on both banks and in the middle of the channel. As a result, the 100-year-floodplain is wider than elsewhere along the stream in both areas.[40]: 13 [41]: 13

While the Beech Ridge unit's floodplain boundary does not include any houses, there are three within it along Route 42 just north of West Kill, making effective flood control here important. The authors of the stream management plan speculate that the kill's lower than expected sinuosity as it flows out of the Spruceton Valley may be the result not of flooding but of an attempt to divert the stream further north and make more of the alluvial land to its south available for farming. While this has not increased the flood risk there, it has made the stream compensate with increased sinuosity further downstream.[40]: 4

The plan notes that, while a comparatively large portion (for the West Kill) of the stream banks have had some sort of revetment installed,[40]: 4 the riparian vegetation along the stream is in many areas lacking. Some mowed areas from adjacent properties in the hamlet come right up to the stream's banks. Japanese knotweed, an invasive species which can displace more appropriate riparian vegetation, was found in several spots; the plan recommends an effort to eradicate the species throughout the entire watershed.[40]: 6

Around Beech Ridge, by contrast, the many channels, resulting in braiding when the stream is at bankfull levels, are the result of past floods. Even modest ones can easily reconfigure the channel, as has happened several times over the late 20th century. The inventory found less stabilization and more erosion on the banks as a result.[41]: 7–10

There was even more knotweed in this section. The erosion on the banks, the plan noted, had the potential to threaten sections of Route 42 alongside. At the bottom of the section the narrowing of the channel just above a private bridge (since destroyed) was causing severe aggradation, possibly worsening any flooding that might occur upstream from it.[41]: 7–10

Six years after that plan was released, that lower portion of the stream saw the most serious flooding from Irene and other events. In 2014, the town's Flood Commission hired Milone & MacBroom, a New Paltz engineering firm, to evaluate various options related to the stream course between the hamlets of West Kill and Lexington. Two years later, after having run computer simulations of flood events at all frequency levels up to 500-year, the firm concluded that the only option which provided benefit worth the cost was to replace the lowest bridge over the West Kill on Route 42, just below where Loucks Road forks off to the west.[38]: 36

Milone & MacBroom explained that the former bridge, due to both the 45-degree angle at which it crossed the West Kill and its height over the stream, constricted the stream flow during 100-year floods. The firm indicated it was consulting with the state Department of Transportation on the design for a new bridge. It called for the bridge's lower chord to be raised a foot; the additional freeboard would allow more water to flow downstream during floods, thus lowering their levels upstream, away from homes and businesses along the road.[38]: 36 In 2017 the bridge was replaced at a cost of $4.1 million, part of a larger ongoing project to replace bridges all over the state; a temporary bridge over the West Kill allowed traffic to continue using the route during construction.[42]

Fishery

Art Flick, author of the influential fly fishing Streamside Guide, published in 1947, lived in Lexington and ran the West Kill Tavern, a short distance up the stream, until his death in 1985. He hosted many visiting anglers, including some celebrities, at his family's West Kill Tavern, a short distance upstream from the Schoharie. When he was not fishing, writing or running the hotel, he was advocating for conservation of the streams.[43]

While trout fishermen today have been advised to avoid the lower West Kill due to the turbidity issues,[44] DEC nevertheless stocks those waters with 700 brown trout yearlings annually, supplementing the stream's native population. Wild rainbow trout are also present, closer to the Schoharie, and brook trout become more common in the Spruceton Valley.[2]

To provide access, DEC has acquired public fishing rights from local landowners in addition to those short stretches where it already owns land adjoining the creek. On the lower stream, these include both sides of the reach that runs alongside Route 42 between the highway's last bridge over the kill to roughly the Roarback Brook confluence and the braided areas from above Beech Ridge Brook to just upstream from the Route 42 bridge at the hamlet of West Kill. Upstream of the hamlet, there is a mile of access on both sides between the state land east of Deyoe Road and the Bennett Brook confluence. A small parking lot at the Spruceton Road bridge upstream from Hagadone Brook is available for anglers, and in the vicinity of Spruceton itself much of the stream is publicly accessible to the unnamed tributary on the south between Styles and Pettit brooks.[2]

See also

Notes

- ↑ This is the elevation that is shown rising at on the U.S. Geological Survey map[7]

- ↑ The floods after Irene reconfigured the site of the station such that its recorded elevation has subsequently been lowered by 5 feet (1.5 m)[32]

- ↑ It is considered likely that most of the chlorides present in the West Kill come from road salt used in the winter to keep Spruceton Road and Route 42 clear[23]

- ↑ The floods washed away the bridge carrying Van Valkenburgh Road, just above the stream's mouth; as of 2018 it has not been replaced and does not look likely to be.[38]: 30

References

- 1 2 "West Kill". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- 1 2 3 "Public Fishing Rights Maps – West Kill" (PDF). New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ "West Kill". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Hydrology and Flood History" (PDF). Catskill Streams. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Geology of the West Kill Watershed" (PDF). Catskill Streams. p. 4. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "2.2 Physiography" (PDF). Catskill Streams. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- 1 2 3 U.S. Geological Survey — Hunter quadrangle — New York (Greene Co.) (Map). 1:24,000. USGS 7 1/2-minute quadrangle maps. Cartography by U.S. Geological Survey. TopoQuest.com. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- 1 2 Northeastern Catskill Trails (Map) (9th ed.). 1:63,3600. NY/NJTC Catskill Trails. Cartography by NY/NJTC. New York–New Jersey Trail Conference. 2010. §§ L5–M5.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey — Lexington quadrangle — New York (Greene Co.) (Map). 1:24,000. USGS 7 1/2-minute quadrangle maps. Cartography by U.S. Geological Survey. TopoQuest.com. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey — Lexington quadrangle — New York (Greene Co.) (Map). 1:24,000. USGS 7 1/2-minute quadrangle maps. Cartography by U.S. Geological Survey. TopoQuest.com. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey — Lexington quadrangle — New York (Greene Co.) (Map). USGS 7 1/2-minute quadrangle maps. Cartography by U.S. Geological Survey. TopoQuest.com. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey — Lexington quadrangle — New York (Greene Co.) (Map). USGS 7 1/2-minute quadrangle maps. Cartography by U.S. Geological Survey. TopoQuest.com. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey — West Kill quadrangle — New York (Greene Co.) (Map). USGS 7 1/2-minute quadrangle maps. Cartography by U.S. Geological Survey. TopoQuest.com. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey — West Kill quadrangle — New York (Greene Co.) (Map). USGS 7 1/2-minute quadrangle maps. Cartography by U.S. Geological Survey. TopoQuest.com. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ↑ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Water Quality" (PDF). Catskill Streams. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ The National Map (Map). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Land Use/Land Cover" (PDF). Catskill Streams. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- 1 2 "Regional Setting" (PDF). Catskill Streams. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- 1 2 "Wetlands & Floodplains" (PDF). Catskill Streams. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ Evers, Alf (1972). The Catskills: From Wilderness to Woodstock. Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0879511623.

The lower slopes of the outer Catskills were hunting grounds and not year-round residences through a thousand years and more of Indian life ... The Indian's physical connection with the Catskills was never great ... Indians were animists—they believed that all parts of the universe and everything in it possessed souls ... they lived at a stage of human development where a mountain may be a kindly mother or a relentless enemy—while still remaining a mountain ... No record remains of how the Catskills looked to the Indians or what part they played in the Indian understanding of life ... But we know beyond doubt of certain roles which the mountains played in the world of the Indians around them. One of them was as a barrier first between groups of Indians differing in language and customs

- 1 2 Ravage, Jessie A. (December 1, 2015). "Historic Resources Survey: Town of Lexington, Greene County, New York" (PDF). p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 12, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ravage, pp. 18–38; accessed June 10, 2020

- ↑ "West Kill Brewing". West Kill Brewing. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "USGS 01349810 West Kill near West Kill NY". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "USGS 01349711 West Kill below Hunter Brook Spruceton NY". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ "USGS Surface-Water Annual Statistics for New York: USGS 01349810 West Kill near West Kill NY". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ "USGS Surface-Water Annual Statistics for New York: USGS 01349711 West Kill below Hunter Brook Spruceton NY". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Stream-related Activities and Permit Requirements" (PDF). Catskill Streams. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ FEMA's National Flood Hazard Layer (Official) (Map). Cartography by Federal Emergency Management Agency. ArcGIS. November 28, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Milone & MacBroom, Inc. (May 2016). "Local Flood Analysis: Town of Lexington Along the Schoharie Creek and the West Kill In the Hamlets of Lexington and West Kill, Greene County, New York" (PDF). Town of Lexington, New York. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- 1 2 "West Kill Stream Management Plan". Catskill Streams. December 31, 2005. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "West Kill Management Unit 15" (PDF). Catskill Streams. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "West Kill Management Unit 17" (PDF). Catskill Streams. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ↑ "Governor Cuomo Announces $13 Million Bridge Replacement Project in Greene County is Underway" (Press release). Albany, New York. New York Governor's office. May 5, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ↑ "Arthur B. Flick Dies; Wrote on Fly Fishing". The New York Times. September 3, 1985. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ↑ Newman, Eric (2010). Flyfisher's Guide to New York. Wilderness Adventures Press. p. 80. ISBN 9781932098792. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

Further reading

Scientific papers with data collected from the West Kill:

- Ernst, Anne G.; Warren, Dana; Baldigo, Barry (July 2012). "Natural-Channel-Design Restorations That Changed Geomorphology Have Little Effect on Macroinvertebrate Communities in Headwater Streams" (PDF). Restoration Ecology. 20 (4): 532–540. doi:10.1111/j.1526-100X.2011.00790.x.

- Ernst, Anne G.; Baldigo, Barry; Warren, Dana R.; Miller, Sarah J. (2010). "Variable Responses of Fish Assemblages, Habitat, and Stability to Natural-Channel-Design Restoration in Catskill Mountain Streams". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 139 (2): 449–467. doi:10.1577/T08-152.1.

- Ernst, Anne G.; Baldigo, Barry; Mulvihill, Christiane I.; Vian, Mark (2010). "Effects of Natural-Channel-Design Restoration on Habitat Quality in Catskill Mountain Streams, New York". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 139 (2): 468–482. doi:10.1577/T08-153.1.

- George, Scott D.; Baldigo, Barry; Smith, Martyn J.; McKeown, Donald M.; Faulring, Jason M. (2016). "Variations in water temperature and implications for trout populations in the Upper Schoharie Creek and West Kill, New York, USA". Journal of Freshwater Ecology. 31 (1): 93–108. doi:10.1080/02705060.2015.1033769.

- Nagle, Peter; Fahey, Timothy J.; Ritchie, Jerry C.; Woodbury, Peter B. (March 15, 2007). "Variations in sediment sources and yields in the Finger Lakes and Catskills regions of New York" (PDF). Hydrological Processes. 21 (6): 828–838. doi:10.1002/hyp.6611. hdl:1813/7661.

- Raymond, Peter A.; Saiers, James E. (September 2010). "Event controlled DOC export from forested watersheds" (PDF). Biogeochemistry. 100 (1–3): 197–209. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1016.2917. doi:10.1007/s10533-010-9416-7.

- Stoddard, John L. (November 1991). "Trends in Catskill Stream Water Quality: Evidence From Historical Data". Water Resources Research. 27 (11): 2855–2864. doi:10.1029/91WR02009.