Surface weather analysis of the hurricane over Charleston on July 14 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | July 11, 1916 |

| Dissipated | July 15, 1916 |

| Category 3 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 115 mph (185 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 960 mbar (hPa); 28.35 inHg (Lowest analyzed[nb 1]) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | ≥84 total |

| Damage | $22 million (1916 USD) |

| Areas affected | |

Part of the 1916 Atlantic hurricane season | |

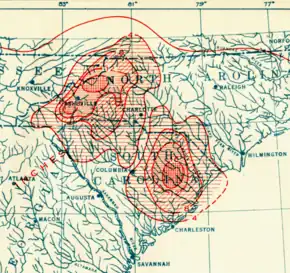

The 1916 Charleston hurricane was a tropical cyclone that impacted parts of the Southeastern United States in July 1916. Torrential rainfall associated with the storm as it moved inland led to the Great Flood of 1916: a prolific and destructive flood event affecting portions of the southern Blue Ridge Mountains. This flood accounted for most of the damage and fatalities associated with the hurricane; most of these occurred in North Carolina The hurricane was first detected as a tropical storm 560 mi (900 km) east of Miami, Florida on July 11. It took an unusually straightforward path towards the Carolinas and strengthened into a hurricane on July 12. The storm's peak sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h)—equivalent to a modern-day Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale—were attained on July 13. It made landfall near Charleston, South Carolina, the next morning, and weakened as it continued inland before losing its tropical cyclone status on July 15 over western North Carolina.

The swath of the hurricane's wind impacts in South Carolina was tightly concentrated around the hurricane's center due to its small size at landfall. The damage in Charleston was widespread but not severe, with most of the damage limited to the downed trees, minor roof and water damage to homes, and shipping damage. Crop damage was severe elsewhere along the coast and farther inland, with a 75–90 percent loss of crops reported north of Charleston along the Santee River. Although the hurricane's winds had tapered off by the time the storm reached North Carolina, the combination of orographic lift and saturated soils induced by an earlier hurricane led to copious rainfall and record-breaking river flooding that began in the southern Blue Ridge Mountains and continued downstream on both sides of the Appalachians. The French Broad River nearly doubled its previous stage record at Asheville, North Carolina, where the floods destroyed numerous buildings. Widespread damage was also wrought to crops, railways, and other infrastructure in the region by the flood-widened rivers. The flooding killed at least 80 people and caused approximately $21 million in damage.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The 1916 Charleston hurricane was the fourth tropical cyclone of the 1916 Atlantic hurricane season.[1] The Weather Bureau noted that it was the first July hurricane on record to originate from near the Bahamas and strike the South Atlantic U.S. coast.[2] While most storms in this region tend to curve towards the northeast upon tracking into higher latitudes, the hurricane took a direct path into the Appalachian Mountains where it would ultimately dissipate. This unusual track was the result of a high pressure area over the Northeastern United States preventing the storm from progressing poleward.[3] The first point entry for the system in HURDAT lists the cyclone as beginning as a tropical storm on July 11, centered approximately 560 mi (900 km) east of Miami, Florida.[nb 2][1] Although the Weather Bureau was cognizant of the tropical cyclone's nature, there were no observations of gale-force winds or low corresponding air pressures at the time. A vessel on July 12 near 27°00′N 72°30′W / 27°N 72.5°W, approximately 50 mi (80 km) south of Charleston, South Carolina, provided the first direct report attesting to the tropical cyclone's presence with observed winds reaching gale-force for the first time.[6] The storm's maximum sustained winds increased as it moved northwest; the storm had intensified into a hurricane by 18:00 UTC on July 12. Intensification continued the next day as the hurricane took a more northward trajectory towards the coast of South Carolina.[1]

At 18:00 UTC on July 13, the hurricane attained its peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h), making it equivalent to a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale.[1] These winds were estimated by a reanalysis of the storm conducted by the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) conducted in 2008, which used a peripheral observed pressure of 961 mbar (hPa; 28.38 inHg) from the ship Hector; the highest maritime winds observed contemporaneously reached only 80 mph (130 km/h).[6] The hurricane held its peak intensity for at least six hours before weakening slightly on its final approach to the South Carolina coast. The hurricane made landfall on Bulls Bay between Charleston, South Carolina, and McClellanville, South Carolina, at around 08:00 UTC on July 14 with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (180 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of approximately 960 mbar (960 hPa; 28 inHg);[1][2] this made the storm the equivalent of a high-end Category 2 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale at landfall.[2][6] The 2008 reanalysis noted that the hurricane may have been stronger than their estimates at landfall. The radius of maximum winds spanned an estimated 23 mi (37 km). At Charleston, the air pressure bottomed out at 983 mbar (29.0 inHg) as the center of the hurricane moved nearby.[6] After moving inland, the storm's winds diminished; they fell below hurricane-force by 18:00 UTC on July 14. The next day, the center of the weakening system crossed into North Carolina. The system was last noted in HURDAT as a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on July 15 within southwestern North Carolina,[1] after which its remnants diffused over the mountainous region.[7]

Preparations, impact, and aftermath

Landfall area

The Weather Bureau described the hurricane as having "unusual severity, though its path of destructiveness was comparatively narrow." There were few clear indications of the storm's approach up to the afternoon prior to the hurricane's landfall on July 13, with tides ahead of the storm only slightly exceeding predicted heights.[2] Warnings were first issued by the bureau on July 12 upon notice of low air pressures from vessels off the Southeastern U.S.[7] The coverage of warnings extended towards the north from their initial issuance as pressures continued to fall along the coast.[7] At their final extents, a hurricane warning ultimately encompassed the U.S. Atlantic coast between Tybee Island, Georgia and Georgetown, South Carolina, while storm warnings were in effect for other coastal stretches between Jacksonville, Florida, and Fort Monroe, Virginia.[8][nb 3] Within these areas, ships were secured in their harbors and ships at sea were forced to divert to safety.[11][12][13] A bulletin issued by the bureau described the storm as possessing "considerable intensity" near the South Carolina coast with peak winds of 64 mph (103 km/h).[8] Most people on Tybee Island evacuated to Savannah once strong winds and high waves began battering the exposed community; parts of the island became submerged as the storm passed nearby on the night of July 13, though the resulting damage was insignificant.[11][10] Trains departing Tybee Island for the mainland traversed miles-long stretches of floodwaters roughly 1 ft (0.30 m) deep.[10] Hundreds of people evacuated to Charleston, South Carolina, from nearby coastal resorts. The buoy tender Cypress evacuated 450 people from Sullivan's Island to Charleston.[12] Ferry and trolley service connecting Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, with nearby islands was stopped on July 13 after wire-bearing poles were brought down by the hurricane.[2] Downed communications lines in McClellanville and Yonges Island in South Carolina prevented dissemination of the hurricane warnings to those locales; couriers dispatched in lieu of telecommunications were unable to deliver the warning information as a result of deteriorating conditions.[2]

The hurricane buffeted Savannah, Georgia, with gale-force winds as it approached the coast.[11] A pilot boat was driven ashore and heavily damaged at Tybee Island. A fisherman off the island was carried out to sea and later drowned after the ship sank. Another four people were rescued in Tybee Inlet after their boat sank.[10] The rough surf kicked up by the storm disrupted communications with Sullivan's Island.[12] The trestle of the railway connecting the island to the mainland sustained enough damage to halt service, but the hurricane's impacts on the island were otherwise light. The damage on the Isle of Palms, South Carolina, was also minor.[14] Fringe effects from the storm were also felt in parts of southeastern North Carolina and inland South Carolina as the storm made landfall.[15][16] In Charlotte, North Carolina, winds from the storm topped out at 56 mph (90 km/h).[7] The high tide at Wilmington, North Carolina, rose to near record levels as a result of the nearby hurricane. Off Beaufort, North Carolina, the loss of two barges prompted a search-and-rescue operation.[17]

The city of Charleston sustained damage from the storm and early reports indicated three deaths in the city and its environs, though the overall damage was described in media reports as not being particularly severe;[18][19] the damage in the city and surrounding areas amounted to less than $100,000.[2] Roadways in the Charleston Battery were first inundated by storm surge on the night of July 13 as waves began to overtop the surrounding seawalls.[20] Tides ultimately rose to 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) higher than normal, placing parts of the Battery under up to 2 ft (0.61 m) of water. Five fires were also sparked during the morning of the hurricane's landfall.[14] Moderate gales continued in Charleston until the night of July 14–15.[7] Damage to shipping was reported in the Charleston area;[21] some small boats sank at their wharves, though most took minor damage.[2] Barges in the Charleston Harbor were set adrift. Offshore, the collier Hector was dealt a heavy blow by the hurricane, prompting the transmission of distress signals; all of her crew were rescued by the Cypress and a tug.[2] The highest observed wind in the city was 64 mph (103 km/h) sustained over a five-minute period.[22] A peak gust of 76 mph (122 km/h) was also recorded on the night of July 13–14, and rainfall accumulation associated with the hurricane reached 4.33 in (110 mm).[2] However, gusts up to 106 mph (171 km/h) were estimated to have battered the area.[14] Most homes in Charleston sustained minor roof and water damage. The high winds also brought down signs and broke plateglass windows.[2] Electric power was shut down during the storm before being restored on the afternoon of July 14;[19][14] one person was electrocuted by a live electric wire.[23] Telegraph and telephone service in Charleston was knocked out of commission with the storm's winds bringing down communications wires connecting the city with surrounding areas, including the loss of service to some 1,500 telephones;[14][18] communications were reestablished after a few hours.[2] The principal markers of the hurricane's impacts in Charleston were the hundreds of trees downed by strong winds.[14] The city's streetcars were brought to a halt by the obstructing debris.[19]

Crop damage characterized most of the impacts between Charleston and the Edisto River. Along the coast of South Carolina north of Charleston, the damage was more severe. An estimated 75–90 percent of crops were lost in the areas north of Charleston around McClellanville and the Santee River; the Weather Bureau estimated that storm surge inundation resulted in millions of dollars in damage to standing timber and crops. Flooding rendered large tracts of crops a total loss around McClellanville. Within the town, the inundation was 4–5 ft (1.2–1.5 m) deep and left behind dead animals and sedge. Poorly-constructed homes were toppled and nearly all trees in McClellanville were uprooted. The destruction of barns led to high livestock casualties. In Georgetown, South Carolina, damage was most marked to trees and shacks; the damage toll there was approximately $25,000. A yacht and several smaller ships at the city sank. Five people were presumed dead following the loss of a barge south of Cape Romain; three bodies later washed ashore. The barge was accompanied by a second barge that also wrecked, though the crew survived. In total, the wreckage of the Hector and the two barges—the only three incidents at sea—represented over $500,000 in damage.[2] There was significant property damage in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, where windows were shattered and beach outhouses were razed. Near-total losses to corn, fruit, and tobacco were reported between Myrtle Beach and Conway, South Carolina, in Horry County. Damage from the hurricane's winds and rain continued into inland South Carolina.[24] High winds fully or partially unroofed homes and felled fences and trees in and around Sumter, South Carolina. One person was killed by a falling tree in Lynchburg, South Carolina. Most of the damage in Sumter County, South Carolina, was dealt to corn and tobacco crops beaten down by the wind; both crops were at critical junctures in their respective agricultural cycles. Cotton also sustained heavy losses. The Sumter Daily Item, a local newspaper, was unable to publish a daily issue for the first time since its establishment.[25] Downed trees and wires were numerous in the Florence, South Carolina, area, including nearby Dartlington where the hurricane was the most severe in years.[26][27]

Great Flood of 1916

A prolific and highly damaging flood event—known locally as the Great Flood of 1916—commenced in the southern Blue Ridge Mountains and Piedmont as the storm moved and decayed inland. The floods inflicted $21 million in damage and claimed an unknown number of lives, though several dozens of fatalities are estimated to have occurred in the Asheville, North Carolina, area;[28] this scale of the devastation was unmatched by prior events.[29][30] The Weather Bureau noted that the precise number of fatalities would never be known, but compiled a death toll of 80 people.[31] The severity of the floods was supported by the atypical track taken by the hurricane directly into the mountainous region and preceding heavy rainfall in the region caused by the remnants of a hurricane earlier in the month. This antecedent rainfall saturated the fertile Appalachian soils, priming the region for intense surface runoff and landslides.[3] The unusual track brought moisture towards the mountain slopes, where they condensed and precipitated upon the saturated grounds.[32] An estimated 80–90 percent of rainfall was not absorbed and became surface runoff, serving as the catalyst for unprecedented river flooding.[31]

North Carolina

Rainfall accumulations between 10–24 in (250–610 mm) were recorded in the watersheds of the Broad and Catawba rivers along the slopes of the Appalachian Mountains between July 14–18.[22] A peak rainfall accumulation of 23.22 in (590 mm) was recorded near Altapass, North Carolina; of this total, 22.22 in (564 mm) fell in a 24-hour period between July 15–16, setting a national record-high 24-hour rainfall total.[3] This measurement remains the state record for 24-hour rainfall.[28] Another station in McDowell County measured 19 in (480 mm) of rain on July 16.[22] The rains in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina and across western and southern sections of the state between July 15–16 was unprecedented. The Weather Bureau remarked that "In some respects it was the most extraordinary rainfall of which there is any authentic record in this country." Numerous streams greatly exceeded previous record high water marks; the French Broad River at Asheville more than doubled the height of its previous flood stage record while the Catawba River at Mount Holly nearly doubled it. Extensive destruction occurred as the rivers expanded past their banks.[3] The Weather Bureau designated areas in three classes based on the extent of damage; Burke, Caldwell, McDowell, Polk, Rutherford, Transylvania, and Wilkes counties in North Carolina comprised Class A, which described the most seriously impacted counties.[3]

Charlotte, North Carolina, recorded 5.04 in (128 mm) of rain in 24 hours, setting an all-time 24-hour rainfall record.[32] Gusty winds and heavy rain began to affect the city on July 13, with gusts above 50 mph (80 km/h) damaging storefronts, uprooting trees, and tearing away awnings and signage. The rain continued for two more days, causing a flood that inundated homes and stores. However, it was surge of water from the excessive rains upstream along the Catawba River that ultimately brought the greatest impacts to the Charlotte area.[33] The Catawba River crested at a record 45.5 ft (13.9 m), some 22.5 ft (6.9 m) above the previous record set in 1908; the 1908 flood had previously been considered the most severe flood in the South Atlantic states. The margin between the water levels reached in 1916 compared to the previous 1908 record diminished downstream but remained record-setting. The high volume of water caused the river to expand; following the 1916 flood, the Catawba River would be 50 ft (15 m) wider at moderate stage than prior to the flood.[31] The floods destroyed bridges, mills, crops, railways, and roads; the flooding of roads disrupted traffic for several weeks.[3] Farms in Burke, Caldwell, Catawba, and McDowell counties were swept bare. Hydroelectric power plants and concrete dams along the river sustained thousands of dollars in damage. While most cotton mills remained standing, they were nonetheless ruined by intruding floodwaters; the destruction of cotton warehouses cemented the significant blow to the cotton industry.[33] Railroads sustained particularly heavy losses due to the floods.[30] Near Mount Holly, thousands of people gathered on two railway bridges to observe the river's rise. These bridges later succumbed to the force of the floodwaters, forcing the onlookers to flee to safety. All bridges along the Southern Railway between Statesville, North Carolina, and Asheville collapsed, which in addition to numerous washouts left passengers marooned for days. Eighteen people were killed in Mayesworth, North Carolina, after a Southern Railway bridge collapsed.[33]

Over 10 in (250 mm) of rain fell throughout the upper French Broad River watershed, with much of that rain falling within 24 hours. The river rapidly rose to an estimated crest of 23.1 ft (7.0 m), accompanied by a flow rate nearly seven times the average annual peak. The nearby Swannanoa River reached a crest of 20.7 ft (6.3 m) with a flow rate over six times the average annual peak.[28] The Asheville area, crossed by the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers, was heavily impacted by flooding.[28] The French Broad River near Asheville had remained at high levels throughout the week preceding the hurricane-fueled rains. Asheville itself was located outside of the heaviest rainfall but was subject to river flooding induced by the upstream rainfall. The first news reports of the city's impending flood came on the afternoon of July 15, when the headwaters of the Swannanoa River rose to flood stage. The flooding reached Asheville by the morning of July 16, destroying buildings, disrupting electric and gas distribution, and placing much of the city underwater.[34] The French Broad River rose rapidly after July 16, and at Asheville the estimated crest was 21 ft (6.4 m). While the banks of the river were ordinarily 381 ft (116 m) across at Asheville (associated with a 4.4 ft (1.3 m) flood stage, the floods bloated the river to about 1,300 ft (400 m) across.[31] The rise of the French Broad River razed hundreds of homes and destroyed other adjacent establishments.[28] In some cases, the floodwaters reached the second stories of buildings. All riverside industrial plants took on major flooding.[31] Riverside Park—once a popular amusement park along the river's banks—was destroyed. All three bridges crossing the river in Asheville were also destroyed. At the entrance of the Biltmore Estate, floodwaters stood 9 ft (2.7 m) deep. Floods upstream of the city destroyed dams, wiping out Asheville's hydropower supply.[28] The dam failures also precipitated the flash flood event that impacted the city.[35]

Elsewhere

The freshet of the excessive North Carolina rains was primarily directed toward South Carolina- and Tennessee-bound rivers while rivers draining into the Atlantic through North Carolina did not experience significant floods.[31] The Santee River and its tributaries experienced one of the most destructive and prolonged floods in its history.[nb 4] Several river gauges measured water levels far exceeding previous records, and a continuous supply of upstream runoff prolonged the elevated water levels. The downstream surge of excess waters blew apart steel railroad and highway bridges within the Santee River system. At its maximum width, the inundation spanned 3–5 mi (4.8–8.0 km). Floods also occurred in the basins of the Black, Lynches, and Pee Dee rivers. The torrential rains and saturated soils ruined crops and resulted in widespread agricultural losses. Roughly 700,000 acres (280,000 hectares) of crops were affected. Many cattle and horses were also swept away.[22] Rivers flowing west into Tennessee from the Blue Ridge Mountains flooded severely. The Tennessee River briefly rose into flood stage at Knoxville, Tennessee, and Chattanooga, Tennessee, as a result of the rains in the river's upper tributaries; at Knoxville the river rose 18 ft (5.5 m) above flood stage.[31] Floods in Newport, Tennessee, forced people to evacuate their homes.[36] The Weather Bureau in 1916 conservatively estimated a $10.3 million damage toll attributable to the floods in the Santee and Pee Dee River basins, with an additional $400,000 in property damage mitigated by the agency's warnings.[22] Of the damage toll, $3.2 million was inflicted in South Carolina and $2 million was inflicted in Tennessee.[36] The New River also carried a surge of floodwaters into Virginia; at Radford, Virginia, the river crested at an estimated 32 ft (9.8 m), some 18 ft (5.5 m) above flood stage, after washing away the flood gauge.[31]

Notes

- ↑ This was the lowest pressure officially listed in connection with the hurricane. The official hurricane database for the Atlantic (HURDAT) indicates the hurricane had this central pressure at 06:00 UTC and 08:00 UTC on July 14, 1916. However, no official pressure is listed for when the hurricane attained its peak sustained winds.[1]

- ↑ HURricane DATa (HURDAT) is the official track database for tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic Ocean and contains information on the positions and intensities of storms dating back to 1851.[4][5]

- ↑ A Weather Bureau storm warning signified the expected approach of a "storm of marked violence" and was further divided into four categories specifying the wind direction. A Weather Bureau hurricane warning signified the expected approach of a hurricane or similarly strong storm. These warnings were signaled using a system of hoisted pennants and flags.[9] Rockets were also used to signal the inclement conditions.[10]

- ↑ Reliable recordkeeping of floods in the Santee River system extend back to 1840.[22]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Scott, J. H. (July 1916). "South Carolina Hurricane of July 13–14, 1916". Monthly Weather Review. Weather Bureau. 44 (7): 404–407. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..404S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<404:SCHOJ>2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Denson, Lee A. (July 1916). "North Carolina Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Columbia, South Carolina: United States Weather Bureau. 19 (7): 51–56. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2021 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Activity" (PDF) (Technical Documentation). Environmental Protection Agency. August 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone History for Southeast South Carolina and Northern Portions of Southeast Georgia". National Weather Service Charleston, South Carolina. North Charleston, South Carolina: National Weather Service. January 9, 2021. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Landsea, Chris; Anderson, Craig; Bredemeyer, William; Carrasco, Cristina; Charles, Noel; Chenoweth, Michael; Clark, Gil; Delgado, Sandy; Dunion, Jason; Ellis, Ryan; Fernandez-Partagas, Jose; Feuer, Steve; Gamanche, John; Glenn, David; Hagen, Andrew; Hufstetler, Lyle; Mock, Cary; Neumann, Charlie; Perez Suarez, Ramon; Prieto, Ricardo; Sanchez-Sesma, Jorge; Santiago, Adrian; Sims, Jamese; Thomas, Donna; Lenworth, Woolcock; Zimmer, Mark (May 2015). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Metadata). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1916/04 - 2008 Revision. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Frankenfield, H. C. (July 1916). "Forecasts and Warnings For July, 1916". Monthly Weather Review. Weather Bureau. 44 (7): 396–399. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..396F. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<396:FAWFJ>2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 "Storm Warnings Displayed". Greenville Daily News. Vol. 42, no. 196. Greenville, South Carolina. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Kenealy, James (1903). "Weather Bureau Stations and Their Duties". Yearbook of the Department of Agriculture. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture. OCLC 12121421.

- 1 2 3 4 "Hurricane Headed For Georgia Coast". The Atlanta Constitution. Vol. 49, no. 29. Atlanta, Georgia. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 "Savannah Shipping Tied Up". Greenville Daily News. Vol. 42, no. 196. Greenville, South Carolina. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 "Charleston Is In Grip Of Hurricane". Greenville Daily News. Vol. 42, no. 196. Greenville, South Carolina. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Shipping Is Tied Up At Charleston". The News and Observer. Vol. 104, no. 14. Raleigh, North Carolina. July 14, 1916. Retrieved February 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Charleston Suffers Little". The Sumter Daily Item. Vol. 44, no. 77. Sumter, South Carolina. July 15, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Reaches Into South Carolina". The Charlotte News. Charlotte, North Carolina. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Felt At Newbern". The Charlotte News. Charlotte, North Carolina. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Wilmington Has High Tides". Salisbury Evening Post. Vol. 12, no. 162. Salisbury, North Carolina. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Strikes Charleston, S.C." Staunton Daily Leader. Vol. 24, no. 180. Staunton, Virginia. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 "Tropical Storm Breaks Over Coast Region Of Georgia And South Carolina With Severity". The Charlotte News. Charlotte, North Carolina. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Sea High at Charleston". The Atlanta Constitution. Vol. 49, no. 29. Atlanta, Georgia. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Two Men Killed At Charleston". Twin City Daily Sentinel. Winston-Salem, North Carolina. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sullivan, Richard H. (July 1916). "South Carolina Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Columbia, South Carolina: United States Weather Bureau. 19 (7): 51–56. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2021 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- ↑ "One Man Killed By Live Wire". The Evening Telegram. Vol. 9, no. 36. Rocky Mount, North Carolina. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Horry County Loss Heavy". The Sumter Daily Item. Vol. 44, no. 77. Sumter, South Carolina. July 15, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Property Loss From Storm Is Very Heavy". The Sumter Daily Item. Vol. 44, no. 77. Sumter, South Carolina. July 15, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Pee Dee Feels Storm's Force". The Sumter Daily Item. Vol. 44, no. 77. Sumter, South Carolina. July 15, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Heavy Storm Hits Darlington". The Sumter Daily Item. Vol. 44, no. 77. Sumter, South Carolina. July 15, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Investigating the Great Flood of 1916". National Centers for Environmental Information. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ↑ Henry, Alfred J. (July 1916). "Rivers and Floods, July, 1916". Monthly Weather Review. Weather Bureau. 44 (7): 407. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..407H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<407a:RAFJ>2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 Day, P. C. (July 1916). "The Weather of the Month". Monthly Weather Review. Weather Bureau. 44 (7): 417–418. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..417D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<417:TWOTM>2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Henry, Alfred J. (August 1916). "Floods in the East Gulf and South Atlantic States, July, 1916". Monthly Weather Review. Weather Bureau. 44 (8): 466–476. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..466H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<466:FITEGA>2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 Atto, O. O. (1916). "The Storm Which Caused The Flood". The North Carolina Flood (PDF). Charlotte, North Carolina: W. M. Bell. pp. 6–8. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2021 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- 1 2 3 Bell, W. M. (1916). "Storm And Flood Viewed From Charlotte". The North Carolina Flood (PDF). Charlotte, North Carolina: W. M. Bell. pp. 9–14. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2021 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ Blankenship, Helen C. (1916). "Asheville, Biltmore and Nearby Points". The North Carolina Flood (PDF). Charlotte, North Carolina: W. M. Bell. pp. 15–36. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ "The Great Flood 1916" (PDF). Asheville, North Caorlina: National Centers for Environmental Information. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- 1 2 Nunn, Roscoe (July 1916). "Tennessee Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Columbia, South Carolina: United States Weather Bureau. 19 (7): 51–54. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2021 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.