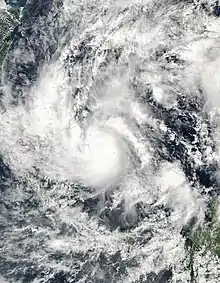

Beta at peak intensity prior to landfall in Nicaragua early on October 30 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 26, 2005 |

| Dissipated | October 31, 2005 |

| Category 3 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 115 mph (185 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 962 mbar (hPa); 28.41 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 9 |

| Damage | $15.5 million (2005 USD) |

| Areas affected | Panama, San Andrés and Providencia, Nicaragua, Honduras |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Beta was a compact and intense tropical cyclone that impacted the southwestern Caribbean in late October 2005. Beta was the twenty-fourth tropical storm, fourteenth hurricane, and seventh and final major hurricane of the record-breaking 2005 Atlantic hurricane season. On October 21, a developing tropical wave entered the eastern Caribbean Sea and spawned Tropical Storm Alpha the following day. As the wave entered the southwestern Caribbean, convection redeveloped and on October 26, the system spawned another low-pressure area which developed into Tropical Depression Twenty-six. The depression intensified into a tropical storm the next morning and was named Beta. By the morning of October 28, the storm intensified into a hurricane, the fourteenth of the season. Beta underwent rapid intensification for several hours to attain its peak intensity with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) on October 30. The storm began to deteriorate before landfall, weakening to Category 2 status as it crossed the Nicaraguan coastline. Rapid weakening followed landfall, and the storm dissipated early the next morning.

Due to the storm's proximity to Central America, several countries were placed on alert and began allocating supplies for a potential disaster. Several hurricane watches and warnings were raised for the small Colombian island of Providencia as well as the Nicaragua and Honduras coastlines. An estimated 150,000 people were evacuated from dangerous regions in Nicaragua and more than 125,000 more were evacuated in Honduras.

As a tropical storm, Beta produced heavy rains over northern Panama, amounting up to 3 inches (76 mm), which caused several mudslides as well as three fatalities. On October 29, the storm passed over Providencia Island, caused significant damage to structures, and injured 30 people. In Honduras and Nicaragua, over 1,000 structures were damaged by the storm, hundreds of which were destroyed. Ten people were initially feared dead after their boat went adrift during the storm. However, a Panamanian vessel rescued the men after drifting in the water for several hours. Rains in Honduras totaled to 21.82 and 6.39 in (554 and 162 mm) in Nicaragua. Six people were killed in Nicaragua as a result of the storm and the cost to repair damages exceeded 300 million córdoba (US$14.5 million). Overall, Beta was responsible for nine fatalities and more than $15.5 million in damage across four countries.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On October 21, a westward-moving tropical wave entered the Caribbean.[1] The wave quickly developed organized convection, indicating that a possible low-pressure area had developed along the wave.[2] Continued development led to the formation of Tropical Depression Twenty-Five (which would later be named Alpha).[3] The wave continued to move towards the west, producing minimal shower and thunderstorm activity.[4] Once in the southwestern Caribbean, the wave slowed, and convection gradually redeveloped on October 25.[5] The next day, with continued organization, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) stated that a tropical depression could develop in the following day or two.[6] At around 18:00 UTC, the NHC determined that Tropical Depression Twenty-Six had developed about 105 miles (169 km) north of the central cost of Panama.[4]

Located within an area of weak vertical wind shear and warm sea surface temperatures, the depression intensified. By 06:00 UTC the next morning, the depression was upgraded to a tropical storm and given the name Beta by the NHC.[4] Beta was slowly moving towards the north-northwest in response to a mid-tropospheric shortwave trough over the Gulf of Mexico and mid-tropospheric ridge to the northeast of the storm. Deep convection developed near the center of circulation, signifying a developing system. With favorable conditions for development, Beta was forecast to intensify into a hurricane before making landfall in central Nicaragua.[7] An eyewall rapidly developed around the center of circulation, fuelling further intensification. With the formation of an eyewall and the compact size of the storm, rapid intensification was anticipated.[8] By the end of October 27, maximum sustained winds around the center of Beta were estimated at 60 mph (97 km/h). An increase in wind shear caused a minor disruption of the storm's structure, briefly preventing strengthening.[4]

After maintaining its intensity for 30 hours, the shear weakened, and Beta began to intensify again.[4] Around 00:00 UTC on October 29, the storm passed near Providencia Island with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h), just below hurricane-status. At this time, the cyclone began to turn towards the west.[4][9] Beta intensified into a hurricane several hours later, with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h), as an eye became pronounced on infrared satellite images. Located south of a weakness within the subtropical ridge, the hurricane's motion slowed to a westward drift.[10] With the formation of an eye, the chances of rapid intensification reached 62%, and the storm could possibly become a major hurricane—a hurricane with winds of 111 mph (179 km/h) or higher—before landfall.[11] Beta continued to intensify as convection deepened around the 11.5 mi (18.5 km) wide eye,[12] strengthening into a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 105 mph (169 km/h).[4]

After undergoing a brief period of rapid intensification from 18:00 UTC on October 29 – 06:00 UTC on October 30, the hurricane reached its peak intensity as a Category 3 hurricane with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 962 mbar (hPa; 28.42 inHg). The storm also began to turn towards the south-southwest as it reached its peak intensity and its maximum size, with tropical storm-force winds extending out 60 mi (97 km) from the center.[4] However, as it neared the coast, cloud tops around the eye began to warm, signifying weakening.[13] Around 12:00 UTC on October 30, Beta made landfall in central Nicaragua near La Barra del Rio Grande with winds of 105 mph (169 km/h).[4] After making landfall, the hurricane weakened to a tropical storm, with winds decreasing to 65 mph (105 km/h), as the structure of the storm began to deteriorate.[14][15] Early on October 31, Beta weakened to a tropical depression and dissipated a few hours later over the mountains of central Nicaragua.[4]

Preparations

Panama, Costa Rica and El Salvador

Although Panama and Costa Rica were not in the direct path of Hurricane Beta,[4] storm warnings were issued for the two countries on October 27 as heavy rains, up to 20 in (510 mm), from the outer bands of Beta were possible.[16] The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Panama alerted officials in Nicaragua, Honduras, Costa Rica, El Salvador and Guatemala about the possible impacts from Beta.[17] Civil defence officials in El Salvador declared a pre-emptive alert due to the possibility of rain-triggered mudslides from the outer bands of Beta.[18]

Colombia

Early on the morning of October 27 the Colombian Government issued a tropical storm warning for the islands of San Andrés and Providencia.[19] Hours later, a hurricane watch was issued.[20] By late morning, both advisories were replaced by a hurricane warning.[21] The island did not have much time to prepare for Hurricane Beta, being struck only three days after its formation. Of its 5,000 residents all stayed to weather the storm but, about 300 of them evacuated wooden homes on the beach for sturdier brick shelters inland on the island's mountains.[22] The neighbouring island of San Andrés initiated a moratorium on all outdoor activities as the storm's outer bands reached the island on October 29.[22] Officials evacuated about 700 people, 500 tourists and 200 residents on San Andrés to temporary shelters. The Colombian Government provided 8 tons (7.2 tonnes) of food and emergency supplies, including 1,100 sheets, 300 hammocks, and 350 cooking kits to the island.[23]

Nicaragua

Immediately upon the storm's formation on October 26, the Government of Nicaragua issued a tropical storm warning for its entire eastern coast.[24] The next day the tropical storm warning was supplemented by a hurricane watch.[21] On October 29, Nicaraguan President Enrique Bolaños declared a maximum "red alert" for the country's eastern coast.[18] Despite the governments efforts, only 10,000 people were evacuated from the Caribbean-side coast[18][22] and the majority secured themselves in their homes.[18] However, the national army reported that 150,000 people were evacuated prior to the storm's arrival.[25] The government pre-positioned food, medicines, clothing, emergency supplies, and army rescue specialists in the most vulnerable areas to provide relief immediately after the storm passed.[18][22] Classes were canceled in all of the country's schools and businesses experienced surging demand for hurricane supplies.[22]

In the city of Puerto Cabezas, population 60,000,[26] meteorologists expected a direct hit.[27] Local authorities announced a curfew to prevent looting.[28] The government also cut off electricity throughout the small coastal city to prevent injuries.[28] Evacuations were limited, and the most vulnerable of the population weathered the storm in poorly constructed shelters.[27] To be able to respond to an emergency following Beta, the government of Nicaragua requested relief supplies for 41,866 families which would last 15 days. These supplies consisted of 98,000 pounds (44,000 kg) of cereals, 628,600 pounds (285,100 kg) of beans, 628,600 pounds (285,100 kg) of corn, 1,257,200 pounds (570,300 kg) of rice, 44,500 pounds (20,200 kg) of sugar, 171,600 pounds (77,800 kg) of salt, 4,929 gal (18,658 L) of cooking oil, 324,900 pounds (147,400 kg) of milk and 21,264 blankets.[29]

Honduras

On October 29, Honduras President Ricardo Maduro declared a State of National Emergency as Beta was forecast to bring heavy rains up to 12 in (300 mm). Three departments, Gracias a Dios, Colon, Olancho and El Paraiso, were placed under Red Alert and mandatory evacuations were put in place. The departments of Atlántida, Yoro, Comayagua, Francisco Morazán and Choluteca were placed under Yellow Alert and a Green Alert was in place for the rest of the country. The Local Emergency Management Agency opened its regional and municipal offices to conduct preparative activities. An emergency radio network was set up to alert the public of any emergencies. The government designated several public schools as shelters for the affected population. In the Francisco Morazán Department, the Tegucigalpa Municipal Emergency Committee opened 73 shelters. Extensive cleaning and garbage disposal was conducted, especially around creeks, rivers, and sewers. The National Armed Forces were placed in strategic areas and were on stand-by for search and rescue operations once the storm passed. About 3,306 tons (3,000 tonnes) of food was reported to be available and local travels in the country were suspended.[30][31] In Tegucigalpa, the emergency committee called for the evacuation of 125,000 people from the most vulnerable areas of the capital.[32] About 8,000 others were evacuated from 50 communities along the Nicaragua border due to the threat of flooding.[33] A hurricane alert was put in place for areas north of the Nicaragua border but was cancelled on October 30 after Beta turned towards the southeast.[34]

Impact

| Country | Persons evacuated | Fatalities | Maximum rainfall | Damage (in USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panama | None | 3 | ~3 in (76 mm) | Unknown |

| Colombia | ~1,000 | 0 | >12 in (300 mm) | Unknown |

| Nicaragua | ~150,000 | 6 | 6.39 in (162 mm) | $6.5 million |

| Honduras | ~133,000 | 0 | 21.82 in (554 mm) | $9 million |

| Total | ~284,000 | 9 | - | >$15.5 million |

Hurricane Beta was responsible for nine fatalities and roughly $15.5 million (2005 USD) in damage across four countries.

Panama

Heavy rains for the outer bands of Hurricane Beta, amounting up to 3 in (76 mm),[35] caused flooding and landslides in Panama. At least 256 people were affected by the storm and 52 homes were damaged; however, the cost of the damages is unknown.[36] At least 50 hectares (120 acres) of rice fields were flooded across the country.[37] One person, a young girl, was killed after the boat she was on sank amid rough seas. Both her parents escaped the sinking ship.[38] Two other people drowned after being swept away by the swollen Chagres River and two others were reported missing.[39]

Providencia Island

Hurricane Beta reached Providencia Island, on October 29, 2005.[4] Rainfall from the storm were estimated over 12 in (300 mm).[35] Roofs were damaged all over the island,[4] and the island's main communications tower was knocked over.[22] A total of 1,660 homes were damaged by the storm throughout the island, leaving 1.4 million Colombian peso (2005 COP; US$681) in repair costs.[40] This disrupted fixed-line telephone service and as the island has no cellular telephone service, it caused a total cessation of communication with the mainland. Beta's arrival on the island was accompanied by a seven-foot storm surge, which damaged beaches, coastal houses and roads, and washed out a tourist footbridge.[22] Coral reefs around the island were, for the most part, untouched, as only 1 percent of the coral sustained minor damage. Minor effects were also found around areas of sea grass. Beaches all around the island lost an average of 9.8 ft (3.0 m) of sand due to erosion.[41] Thirty people were injured[42] and 913 families, a total of 3,074 people, were affected during Hurricane Beta's passage over the island.[43]

Nicaragua

Heavy rains from Hurricane Beta, amounting up to 6.39 in (162 mm), and strong winds caused extensive property damage in Nicaragua.[4] Six people were confirmed to have been killed by Beta in Nicaragua, one of which was caused by a heart attack.[44][45] It was initially feared that ten others, who were listed as missing, were killed when their vessel disappeared during the storm,[46] but they were later rescued by a Panamanian vessel after drifting in the waters for several hours.[47] Throughout the country, a total of 376 latrines, 215 homes, two schools, two community children centres, two community water tanks and five solar panels were destroyed. An additional 852 homes, 21 schools, and three health centres were damaged. The cost to repair damages caused by the hurricane were estimated at $2.1 million (2006 USD).[48] A total of 2,668 people were left homeless as a result of the storm.[49]

Two communities of Miskitos, with a total population of 3,200, were isolated during the storm.[50] Nearly 80 percent of the homes in four communities along the Caribbean coast near Bluefields were destroyed by the storm.[51] The strong winds from Beta levelled 1,200,000 acres (4,900 km2) of forested land.[52] Agricultural damage from the storm in Nicaragua amounted to 67 million córdoba (US$4 million).[53] Structural damage amounted to 35 million córdoba (US$1.6 million).[54] Damage to roadways throughout the country left over 20 million córdoba (US$979,000) in damages.[55] Offshore, the damage to algae, mangroves, and other aquatic life was severe. Hundreds of dead fish washed up along the coastline in the days following Beta.[56]

Honduras

Torrential rains, peaking at 21.82 in (554 mm),[4] caused numerous mudslides which isolated several communities. Widespread damage occurred to structures, with numerous roofs being torn off.[4] Signs, trees, power poles, and telephone poles were knocked down due to the wind. Four rivers overflowed and communications were disrupted across areas near the Nicaragua border.[33] An estimated 60,483 people were affected by the storm in the country. A total of 954 homes and 11 bridges were destroyed while another 237 homes, 30 roads, 30 bridges and 66 drinking water systems were damaged. A total of 7,692.1 acres (3,112.9 ha) of farmland was destroyed.[57] At least 11,000 people were left stranded by the storm.[58] Throughout the country, damage was estimated at 170 million lempira (US$9 million).[59]

Aftermath

Colombia

On Providencia Island, two teams of aid personnel, consisting of a total of 800 people, from National Intervention Teams were mobilized in response to Beta. The Colombian Red Cross Society and the National Disaster Response and Preparedness System (SNPAD) provided assistance to 600 families with non-food relief, pre-hospital care, first aid, temporary shelter and psychosocial support, and carried out a preventative health campaign on the island.[43] On October 29, Diego Palacio, the Minister of Social Protection, flew to Providencia to assess the damage caused by Beta.[60] A frigate was also deployed to the island, carrying two tons of relief items along with 130 search and rescue workers.[61] Reconstruction on the island took place shortly after the storm dissipated and 60 percent of the structures were repaired by January 20, 2006. The completion date for repairs was set at the third week of February.[62]

Nicaragua

The SNPAD in Nicaragua distributed food to 1,500 victims and reported that food was needed for an additional 35,000 people.[63] Roughly 300 million córdoba was required to repair roadways throughout the affected region.[55] On November 1, the government of Nicaragua announced that it would assist in the reconstruction and repair of 334 for the Miskito Indians.[64] By November 7, airlifts from Managua were able to bring roughly 60 tons (54 tonnes) of supplies to natives living along the Coco River. Additionally, plans for a four-month operation to supply the Miskito Indians with food were implemented. In attempts to lessen the effects of disease and famine, 5,000 tons (4,536 tonnes) of food was planned to be distributed in the region during this time.[65]

Ahead of Hurricane Beta, the U.S. ambassador to Nicaragua signed a disaster declaration on October 28, prompting the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) to send aid. Before the storm hit, $200,000 was sent to the country for emergency relief supply distribution and helicopter fuel. On November 1, USAID and OFDA airlifted 200 rolls of plastic sheeting, 5,020 ten-litre water containers, and 2,736 hygiene kits, valued at $120,877. Another $22,000 was used to supply an aircraft and Bell 204/205 helicopter to assist affected areas. On November 10, another $100,000 was sent for sanitation and health activities.[66] The United Nations sent $10,000 to the South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region to cover emergency needs. Forty-five tents were sent to communities in need.[63] The Spanish Government also sent $377,188 in aid and to Nicaragua.[67]

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement sent 300 food packages, 300 kitchen kits, 200 mattresses, 300 hygiene kits, 150 hammocks, plastic sheeting, and 26.4 tons (24 tonnes) of construction materials and tools to Nicaragua. As a precaution, about 2.2 tons (2 tonnes) of food was also sent to the National Society's warehouse in Bogotá. A total of $116,367 was also allocated from disaster relief funds.[33] The Justice, Global & Ecumenical Relations Unit in Canada also provided $6,500 in relief funds to Nicaragua.[68] Two shipments of relief supplies were sent to the hardest hit areas by Direct Relief. The first shipment arrived on November 9; it contained 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) of antibiotics valued at $237,241. The second shipment arrived on November 22; it contained numerous supplies, valued at $139,283, which would be delivered to the hardest hit areas.[69] The governments of Sweden and France sent $37,191 and $36,058 in funds respectively.[67]

Honduras

On October 31, a disaster declaration was signed for Honduras due to the effects from Beta. USAID sent $50,000 in funds for the purchase of relief items such as blankets, foam mattresses, and hygiene kits. Two Fokker F27 aircraft were also supplied to help assist the transportation of relief supplies at a cost of $40,000. The United States Department of Defense sent military personnel to the affected areas from November 4–8. During that time, more than 155,000 pounds (70,000 kg) of relief supplies were airlifted to the affected communities. The United States embassy in Honduras also provided a C-12 Huron aircraft to transport 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) to Puerto Lempira.[66] A total of $500,000 was sent in the form of relief supplies and transport to Honduras from USAID.[70] The Spanish Government offered a C-130 Hercules containing emergency supplies to Honduras. The World Food Programme pre-positioned 509 tons (461.7 tonnes) of food to be used in temporary shelters and recovery activities. The government of Great Britain offered humanitarian assistance, consisting of 1,500 plastic bags, 1,800 jerrycans, one helicopter, five boats, 250 military personnel, and five medical assistants.[71]

Naming and records

- When Tropical Depression Twenty-six developed into a tropical storm, it marked the first time that the second letter of the Greek alphabet was used as the name of an Atlantic storm. The next one to be so named was Tropical Storm Beta in 2020.[72]

- Beta's record-setting formation date as the season's 24th tropical or subtropical storm would stand until 2020, when broken by Hurricane Gamma, which formed on October 3.[73]

- Operationally, Beta was the record-breaking 13th hurricane, surpassing the 12 hurricanes produced in 1969.[74] In the post-season analysis by the National Hurricane Center, Tropical Storm Cindy was upgraded to a hurricane, thus making Beta the 14th hurricane of 2005.[75]

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2005

- Timeline of the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season

- List of Category 3 Atlantic hurricanes

- Hurricane Cesar–Douglas (1996) – Made landfall in nearly the same location.

- Hurricane Rina (2011) – Similarly slow-moving storm that affected similar areas.

- Hurricane Otto (2016) – Storm of a similar track and intensity that struck Nicaragua in 2016.

- Hurricane Eta (2020) – A Category 4 hurricane that impacted similar areas

References

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (October 21, 2005). "Tropical Weather Outlook: October 21, 2005 08Z". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 28, 2008.

- ↑ Knabb, Richard (October 21, 2005). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Weather Service Raw Text Product. Miami, Florida: Iowa State University. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ↑ Knabb, Richard; Mainelli, Michelle (October 22, 2005). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Weather Service Raw Text Product. Miami, Florida: Iowa State University. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Richard J. Pasch; David P. Roberts (March 28, 2006). "Tropical Cyclone Report, Hurricane Beta, 26–31 October 2005" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- ↑ Beven, Jack (October 22, 2005). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Weather Service Raw Text Product. Miami, Florida: Iowa State University. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ↑ Beven, Jack (October 22, 2005). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Weather Service Raw Text Product. Miami, Florida: Iowa State University. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ↑ Richard Knabb (October 27, 2005). "Tropical Storm Beta Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Jack Beven (October 27, 2005). "Tropical Storm Beta Discussion Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (October 29, 2005). "Tropical Storm Beta Discussion Nine". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Stacy Stewart (October 20, 2005). "Hurricane Beta Discussion Ten". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Jack Beven (October 29, 2005). "Hurricane Beta Discussion Eleven". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Jack Beven (October 30, 2005). "Hurricane Beta Discussion Twelve". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Richard Knabb (October 30, 2005). "Hurricane Beta Discussion Fourteen". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ James Franklin (October 30, 2005). "Hurricane Beta Discussion Fifteen". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ James Franklin (October 30, 2005). "Tropical Storm Beta Discussion Sixteen". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Ivan Castro (October 27, 2005). "Tropical Storm Beta bears down on Central America". redOrbit.com. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ↑ United Nations (October 27, 2005). "Tropical Storm Beta Becomes 23rd Named Storm in 2005". Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Archived from the original on July 27, 2007. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Staff Writer (October 30, 2005). "Nicaragua evacuates thousands as Hurricane Beta approaches". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ Richard Knabb (October 27, 2005). "Tropical Depression Twenty-Six Intermediate Advisory One-A". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ↑ Richard Knabb (October 27, 2005). "Tropical Storm Beta Public Advisory Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- 1 2 Jack Beven (October 27, 2005). "Tropical Storm Beta Public Advisory Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Staff Writer (October 29, 2005). "Beta hits island of Providencia". CNN. Archived from the original on February 2, 2006. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ↑ "Island Evacuates Before Beta Strikes". Fox News. Associated Press. October 27, 2005. Retrieved December 28, 2008.

- ↑ Avila (October 26, 2005). "Tropical Depression Twenty-Six Public Advisory One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ↑ Carlos Salinas (October 27, 2005). "Prevén 150,000 evacuados por "Beta"" (in Spanish). El Nuevo Diario. Archived from the original on November 13, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Nicaragua orders evacuations as hurricane looms". ABC News Online. AFP. October 30, 2005. Retrieved October 4, 2005.

- 1 2 Staff Writer (October 30, 2005). "Hurricane Beta reaches Category 3 intensity". CNN. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- 1 2 AFX News (October 30, 2005). "Hurricane Beta Hits Nicaragua, Falters - latimes". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 3, 2005.

- ↑ "Nicaragua – Tropical Storm Beta". Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. October 28, 2005. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ↑ Office of the United Nations Resident Coordinator in Honduras (October 28, 2005). "Tropical Storm "Beta" Situation Report No.2". United Nations. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- ↑ Government of Honduras (October 29, 2005). "Honduras: Presidente Maduro y alcalde capitalino supervisan dragado de ríos" (in Spanish). ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Hurricane Beta strengthens". The Age. Australia. Reuters. October 30, 2005. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Colombia and Nicaragua: Hurricane Beta" (PDF). International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. October 31, 2005. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ↑ Bayardo Mendoza (October 30, 2005). "Hurricane Beta Pounds Nicaragua Coast". redOrbit.com. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- 1 2 Hal Pierce and Steve Lang (2005). "2005 Atlantic Hurricane Season Marches On With Alpha and Beta". Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (NASA). Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ↑ Patricia Ramírez y Eladio Zárate (2006). "2005 Año de récords hidrometeorológicos en Centroamérica" (in Spanish). Comité Regional de Recursos Hidráulicos del Istmo Centroamericano. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved December 28, 2008.

- ↑ Wilder Pérez R. (October 28, 2005). "Beta apunta a Nicaragua" (in Spanish). La Prensa. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ↑ Pérez R. Wilder (October 28, 2005). "Beta apunta a Nicaragua". La Prensa (in Spanish). Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ↑ Staff Writer (October 29, 2005). "Perecen dos panameños por la tormenta tropical "Beta"" (in Spanish). El Siglo De Durango. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ↑ Government of Colombia (April 10, 2006). "Colombia: $ 1.409 millones costó recuperación de Providencia" (in Spanish). ReliefWeb. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- ↑ Alberto Rodríguez-Ramírez y María Catalina Reyes-Nivia (April 3, 2008). "Evaluación Rápida de los Effectos del Huracán Beta en la Isla Providencia" (PDF) (in Spanish). José Benito Vives de Andréis Marine and Coastal Research Institute. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ↑ "Beta Drenches Central America". Fox News. Associated Press. October 30, 2005. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- 1 2 "Colombia: Floods" (PDF). Colombia Red Cross Society. November 18, 2005. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ↑ Martin Parry, and Osvaldo Canziani (2008). "Climate Change 2007" (PDF). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 24, 2008. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ↑ Plan (November 2, 2005). "Nicaragua: Current issues facing communities". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ↑ "Hurricane Beta hits Nicaragua, triggers heavy rains in Honduras, Costa Rica". People's Daily Online. Xinhua News. October 31, 2005. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ↑ Gustavo Álvarez Y Valeria Imhof (October 31, 2005). ""Beta" se ensañó en tres municipios" (in Spanish). El Nuevo Diario. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ↑ Hannah GivenWilson (November 14, 2005). "US$2.1 million required to repair infrastructure damage from Beta". Nicaragua News Service. Archived from the original on September 21, 2006. Retrieved December 28, 2008.

- ↑ Agence-France-Presse (November 2, 2005). "Beta empeoró pobreza de indígenas del Caribe". La Prensa (in Spanish). Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ↑ Deutsche Presse-Agentur (October 31, 2005). "Hurricane Beta dissipating over Nicaragua". Monsters and Critics. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved December 28, 2008.

- ↑ "Hurricane Beta hits Nicaragua, triggers heavy rains in Honduras, Costa Rica". People's Daily Online. Xinhua News. October 31, 2005. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ↑ Action by Churches Together International (November 18, 2005). "ACT Appeal Nicaragua – Hurricane Beta – LACE 53". Reliefweb. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ↑ Giorgio Trucchi (November 16, 2005). "Nicaragua: Abandono y desesperación en la Costa Caribe después del Huracán "Beta"" (in Spanish). UITA. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ↑ Sergio León C. (November 8, 2005). "Costa necesita 35 millones de córdobas a causa de Beta" (in Spanish). La Prensa. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2010.

- 1 2 Carlos Salinas (November 1, 2005). "Reconstrucción costará 300 millones". El Nuevo Diario (in Spanish). Archived from the original on July 6, 2009. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ↑ Sergio León C. (November 3, 2005). "Beta contaminó zonas en RAAS". La Prensa. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ↑ Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (November 30, 2005). "ACT Appeal Central America – Hurricane Beta – LACE 53 (Revision 1)" (PDF). ReliefWeb. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ↑ "Hundreds evacuated as more rain drenches Honduras". ReliefWeb. Reuters. November 2, 2005. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ↑ EFE (November 4, 2005). "Calculan en unos nueve millones de dólares las pérdidas causadas por lluvias en Honduras" (in Spanish). 7dias. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ↑ Staff Writer (October 29, 2005). "Clima.- 'Beta' no deja víctimas mortales en San Andrés y Providencia, a su paso por Colombia" (in Spanish). Lexur. Archived from the original on June 23, 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- ↑ Staff Writer (October 29, 2005). "El Huracán 'Beta' comienza retiro de Providencia" (in Spanish). Caracol Radio. Archived from the original on April 19, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- ↑ Ministry of Foreign Affairs (November 18, 2005). "Colombia, A Positive Country". Coordination of Internal and External Communication Affairs. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- 1 2 "OCHA Situation Report No. 4 Nicaragua:Hurricane Beta". Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. November 3, 2005. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ↑ Julia Ríos (November 1, 2005). "Gobierno promete reconstruir zona afectada por Beta". Agence-France-Presse (in Spanish). La Prensa. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ↑ EFE (November 7, 2005). "Mal clima impide llevar ayuda al Caribe" (in Spanish). La Prensa. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- 1 2 "Latin America and the Caribbean –Hurricane Season 2005" (PDF). United States Agency for International Development. November 10, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2008. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- 1 2 "Nicaragua (Caribbean) – Hurricane Beta – October 2005" (PDF). Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. December 12, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ↑ "Emergency Responses and Relief 2005 Disbursements". The United Church of Canada. September 3, 2008. Archived from the original on June 29, 2007. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ↑ Direct Relief International (November 30, 2005). "Nicaragua: Direct Relief's programme activities update Nov 2005". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ↑ Bureau of International Information Programs, U.S. Department of State (January 16, 2006). "The United States Gives Latin America $21 Million in Disaster Relief". FindLaw. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ↑ Office of the United Nations Resident Coordinator in Honduras (October 30, 2005). "Tropical Storm "Beta" Situation Report No.2". United Nations. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ↑ Morales, Christina; Waller, Allyson; Hauser, Christine (September 20, 2020). "Tropical Storm Beta Draws Warnings in Gulf Coast States". The New York Times. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ↑ Discher, Emma (October 2, 2020). "Tropical Storm Gamma develops over Caribbean Sea; here's the latest forecast". nola.com. New Orleans, Louisiana. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ↑ Gutro, Rob (October 27, 2005). "2005 Hurricane Season Marches on with Alpha and Beta". nasa.gov. Greenbelt, Maryland: Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (February 14, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Cindy (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

External links

- The National Hurricane Center's Tropical Cyclone Report on Hurricane Beta

- The National Hurricane Center's Advisory Archive for Hurricane Beta