| One World Trade Center | |

|---|---|

| |

.jpg.webp) One World Trade Center in June 2021 | |

| Alternative names |

|

| Record height | |

| Tallest in North America and the Western Hemisphere since 2013[I] | |

| Preceded by | Willis Tower |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Type |

|

| Architectural style | Contemporary modern |

| Location | 285 Fulton Street Manhattan, New York City, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°42′47″N 74°00′48″W / 40.71306°N 74.01333°W |

| Construction started | April 27, 2006 |

| Topped-out | May 10, 2013[2] |

| Opened | November 3, 2014[3][4] May 29, 2015 (One World Observatory)[5] |

| Cost | US$3.9 billiona[6][7] |

| Height | |

| Architectural | 1,776 ft (541.3 m)[8][9] |

| Tip | 1,792 ft (546.2 m)[8] |

| Antenna spire | 407.9 ft (124.3 m) |

| Roof | 1,368 ft (417.0 m)[10] |

| Top floor | 1,268 ft (386.5 m)[8] |

| Observatory | 1,268 ft (386.5 m)[8] |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 94 (+5 below ground) (28 mechanical)[8][11] |

| Floor area | 3,501,274 sq ft (325,279 m2)[8] |

| Lifts/elevators | 73[8] made by ThyssenKrupp[12] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | |

| Developer | Port Authority of New York and New Jersey[8] |

| Engineer | Jaros, Baum & Bolles (MEP)[8] |

| Structural engineer | WSP Cantor Seinuk |

| Other designers | Hill International, The Louis Berger Group[14] |

| Main contractor | Tishman Construction |

| Website | |

| onewtc | |

| References | |

| [8][15] | |

|

| |

One World Trade Center, also known as One World Trade, One WTC, and formerly called the Freedom Tower during initial planning stages,[note 1] is the main building of the rebuilt World Trade Center complex in Lower Manhattan, New York City. Designed by David Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, One World Trade Center is the tallest building in the United States, the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere, and the seventh-tallest in the world. The supertall structure has the same name as the North Tower of the original World Trade Center, which was destroyed in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The new skyscraper stands on the northwest corner of the 16-acre (6.5 ha) World Trade Center site, on the site of the original 6 World Trade Center. It is bounded by West Street to the west, Vesey Street to the north, Fulton Street to the south, and Washington Street to the east.

The construction of below-ground utility relocations, footings, and foundations for the new building began on April 27, 2006. One World Trade Center became the tallest structure in New York City on April 30, 2012, when it surpassed the height of the Empire State Building. The tower's steel structure was topped out on August 30, 2012. On May 10, 2013, the final component of the skyscraper's spire was installed, making the building, including its spire, reach a total height of 1,776 feet (541 m). Its height in feet is a deliberate reference to the year when the United States Declaration of Independence was signed. The building opened on November 3, 2014;[4] the One World Observatory opened on May 29, 2015.[5]

On March 26, 2009, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) confirmed that the building would be officially known by its legal name of "One World Trade Center", rather than its colloquial name of "Freedom Tower".[16][17][18] The building has 94 stories, with the top floor numbered 104.

The new World Trade Center complex will eventually include five high-rise office buildings built along Greenwich Street, as well as the National September 11 Memorial & Museum, located just south of One World Trade Center where the original Twin Towers stood. The construction of the new building is part of an effort to memorialize and rebuild following the destruction of the original World Trade Center complex.

History

Original building (1971–2001)

The construction of the original World Trade Center was conceived as an urban renewal project and spearheaded by David Rockefeller. The project was intended to help revitalize Lower Manhattan.[19] The project was planned by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which hired architect Minoru Yamasaki.[20] The twin towers at 1 and 2 World Trade Center were designed as framed tube structures, giving tenants open floor plans, unobstructed by columns or walls.[21][22] One World Trade Center was the North Tower, and Two World Trade Center was the South Tower.[23] Each tower was over 1,350 feet (410 m) high, and occupied about 1 acre (0.40 ha) of the total 16 acres (6.5 ha) of the site's land.[24] Of the 110 stories in each tower, 8 were set aside as mechanical floors. All the remaining floors were open for tenants. Each floor of the tower had 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2) of available space. The North and South tower had 3,800,000 square feet (350,000 m2) of total office space.[25]

Construction of the North Tower began in August 1966; extensive use of prefabricated components sped up the construction process. The first tenants moved into the North Tower in October 1971.[26][27] At the time, the original One World Trade Center became the tallest building in the world, at 1,368 feet (417 m) tall. After a 360-foot (110 m)-tall antenna was installed in 1978, the highest point of the North Tower reached 1,728 ft (527 m).[28] In the 1970s, four other low-level buildings were built as part of the World Trade Center complex.[29][30] A seventh building was built in the mid-1980s.[31][32] The entire complex of seven buildings had a combined total of 13,400,000 square feet (1,240,000 m2) of office space.[29][30][33]

Destruction

At 8:46 a.m. (EDT) on September 11, 2001, five hijackers affiliated with al-Qaeda crashed American Airlines Flight 11 into the northern facade of the North Tower between the 93rd and 99th floors.[34][35] Seventeen minutes later, at 9:03 a.m. (EDT), a second group of five terrorists crashed the hijacked United Airlines Flight 175 into the southern facade of the South Tower, striking between the 77th and 85th floors.[36]

By 9:59 a.m. (EDT), the South Tower collapsed after burning for approximately 56 minutes. After burning for 102 minutes, the North Tower collapsed due to structural failure at 10:28 a.m. (EDT).[37] When the North Tower collapsed, debris fell on the nearby 7 World Trade Center, damaging it and starting fires. The fires burned for hours, compromising the building's structural integrity. Seven World Trade Center collapsed at 5:21 p.m. (EDT).[38][39]

Together with a simultaneous attack on the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, and a failed plane hijacking that resulted in a plane crash in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, the attacks resulted in the deaths of 2,996 people (2,507 civilians, 343 firefighters, 72 law enforcement officers, 55 military personnel, and the 19 hijackers).[40][41][42] More than 90% of the workers and visitors who died in the towers had been at or above the points of impact.[43] In the North Tower, 1,355 people at or above the point of impact were trapped, and died of smoke inhalation, fell, jumped from the tower to escape the smoke and flames, or were killed when the building eventually collapsed. One stairwell in the South Tower, Stairwell A, somehow avoided complete destruction, unlike the rest of the building.[44] When Flight 11 hit, all three staircases in the North Tower above the impact zone were destroyed, making it impossible for anyone above the impact zone to escape. 107 people below the point of impact also died.[43]

Current building (2013–present)

| World Trade Center |

|---|

| Towers |

| Other elements |

| Artwork |

| History |

Planning

Following the destruction of the original World Trade Center, there was debate regarding the future of the World Trade Center site. There were proposals for its reconstruction almost immediately, and by 2002, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation had organized a competition to determine how to use the site.[45] The proposals were part of a larger plan to memorialize the September 11 attacks and rebuild the complex.[46][47] Already the site was becoming a tourist attraction; in the year following the attacks the Ground Zero site became the most visited place in the United States. On September 10, 2002, the Viewing Wall, a temporary display containing information about the attacks and listing the names of the dead, opened to the public.[48]

When the public rejected the first round of designs, a second, more open competition took place in December 2002, in which a design by Daniel Libeskind was selected as the winner in February 2003. Other designs were submitted by Richard Meier, Peter Eisenman, Charles Gwathmey, and Steven Holl; William Pedersen; and Foster and Partners.[48] This design underwent many revisions, mainly because of disagreements with developer Larry Silverstein, who held the lease to the World Trade Center site at that time.[49] Peter Walker and Michael Arad's "Reflecting Absence" proposal was selected as the site's 9/11 Memorial in January 2004.[48]

There was criticism concerning the limited number of floors that were designated for office space and other amenities in an early plan. Only 82 floors would have been habitable, and the total office space of the rebuilt World Trade Center complex would have been reduced by more than 3,000,000 square feet (280,000 m2) in comparison with the original complex.[9] The floor limit was imposed by Silverstein, who expressed concern that higher floors would be a liability in the event of a future terrorist attack or other incident. Much of the building's height would have consisted of a large, open-air steel lattice structure on the roof of the tower, containing wind turbines and "sky gardens".[9]

In a subsequent design, the highest occupiable floor became comparable to the original World Trade Center, and the open-air lattice was removed from the plans.[9] In 2002, former New York Governor George Pataki faced accusations of cronyism for supposedly using his influence to get the winning architect's design picked as a personal favor for his friend and campaign contributor, Ronald Lauder.[50]

A final design for the "Freedom Tower" was formally unveiled on June 28, 2005. To address security issues raised by the New York City Police Department, a 187-foot (57 m) concrete base was added to the design in April of that year. The design originally included plans to clad the base in glass prisms in order to address criticism that the building might have looked uninviting and resembled a "concrete bunker". However, the prisms were later found to be unworkable, as preliminary testing revealed that the prismatic glass easily shattered into large and dangerous shards. As a result, it was replaced by a simpler facade consisting of stainless steel panels and blast-resistant glass.[51]

Contrasting with Libeskind's original plan, the tower's final design tapers octagonally as it rises. Its designers stated that the tower would be a "monolithic glass structure reflecting the sky and topped by a sculpted antenna." In 2006, Larry Silverstein commented on a planned completion date: "By 2012 we should have a completely rebuilt World Trade Center, more magnificent, more spectacular than it ever was."[52] On April 26, 2006, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey approved a conceptual framework that allowed foundation construction to begin. A formal agreement was drafted the following day, the 75th anniversary of the 1931 opening of the Empire State Building. Construction began in May; a formal groundbreaking ceremony took place when the first construction team arrived.[53]

Construction

The symbolic cornerstone of One World Trade Center was laid in a ceremony on July 4, 2004.[54] The stone had an inscription supposedly written by Arthur J. Finkelstein.[55] Construction was delayed until 2006 due to disputes over money, security, and design.[54] The last major issues were resolved on April 26, 2006, when a deal was made between developer Larry Silverstein and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, so the cornerstone was temporarily removed from the site on June 23, 2006.[56] Soon after, explosives were detonated at the construction site for two months to clear bedrock for the building's foundation, onto which 400 cubic yards (310 cubic meters) of concrete was poured by November 2007.[57] In a December 18, 2006, ceremony held in nearby Battery Park City, members of the public were invited to sign the first 30-foot (9.1 m) steel beam installed onto the building's base.[58][59] It was welded onto the building's base on December 19, 2006.[60] Foundation and steel installation began shortly afterward, so the tower's footings and foundation were nearly complete within a year.[61] An estimate in February 2007 placed the initial construction cost of One World Trade Center at about $3 billion, or $1,150 per square foot ($12,400/m2).[62]

In January 2008, two cranes were moved onto the site. Construction of the tower's concrete core, which began after the cranes arrived,[61] reached street level by May 17. The base was not finished until two years later, after which construction of the office floors began and the first glass windows were installed; during 2010, floors were constructed at a rate of about one per week.[63] An advanced "cocoon" scaffolding system was installed to protect workers from falling, and was the first such safety system installed on a steel structure in the city.[64] The tower reached 52 floors and was over 600 feet (180 m) tall by December 2010. The tower's steel frame was halfway complete by then,[65] but grew to 80 floors by the tenth anniversary of the September 11 attacks, at which time its concrete flooring had reached 68 floors and the glass cladding had reached 54 floors.[66]

In 2009, the Port Authority changed the official name of the building from "Freedom Tower" to "One World Trade Center", stating that this name was the "easiest for people to identify with."[1][67] The "Freedom Tower" name had also been subject to ridicule on programs like Saturday Night Live. The name change also served a practical purpose: real estate agents believed that it would be easier to lease space in a building with a traditional street address.[48] The change came after board members of the Port Authority voted to sign a 21-year lease deal with Vantone Industrial Co., a Chinese real estate company, which would become the building's first commercial tenant to sign a lease. Vantone planned to create the China Center, a trade and cultural facility, covering 191,000 square feet (17,700 m2) on floors 64 through 69.[68]

Mass media company Condé Nast became One WTC's anchor tenant in May 2011, leasing 1 million square feet (93,000 m2) and relocating from 4 Times Square.[69][70] While under construction, the tower was specially illuminated on several occasions. For example, it was lit in red, white, and blue for Independence Day and the anniversary of the September 11 attacks, and it was illuminated in pink for Breast Cancer Awareness Month.[71] The tower's loading dock could not be finished in time to move equipment into the completed building, so five temporary loading bays were added at a cost of millions of dollars. The temporary PATH station was not to be removed until its official replacement, the World Trade Center Transportation Hub, was completed, blocking access to the planned loading area.[72] Chadbourne & Parke, a Midtown Manhattan-based law firm, was supposed to lease 300,000 square feet (30,000 m2) in January 2012,[73] but the deal was abruptly canceled that March.[74]

Topping-out and completion

.jpg.webp)

By March 2012, One WTC's steel structure had reached 93 stories,[75] growing to the 94th story (labeled as floor 100[76]) and 1,240 feet (380 m) by the end of the month.[76] The tower's estimated cost had risen to $3.9 billion by April 2012, making it the most expensive building in the world at the time.[6][7] The tower's construction was partly funded by approximately $1 billion of insurance money that Silverstein received for his losses in the September 11 attacks.[62] The State of New York provided an additional $250 million, and the Port Authority agreed to give $1 billion, which would be obtained through the sale of bonds.[77] The Port Authority raised prices for bridge and tunnel tolls to raise funds, with a 56 percent toll increase scheduled between 2011 and 2015; however, the proceeds of these increases were not used to pay for the tower's construction.[7][78]

The still-incomplete tower became New York City's tallest building by roof height in April 2012, passing the 1,250-foot (380 m) roof height of the Empire State Building.[79][80] President Barack Obama visited the construction site two months later and wrote, on a steel beam that would be hoisted to the top of the tower, the sentence "We remember, we rebuild, we come back stronger!"[81] That same month, with the tower's structure nearing completion, the owners of the building began a public marketing campaign for the building, seeking to attract visitors and tenants.[82]

One World Trade Center's steel structure topped out at the 94th physical story (numbered as floor 104), with a total height of the roof top at 1,368 feet (417 m), in August 2012.[51][83] The tower's spire was then shipped from Quebec to New York in November 2012,[84][85] following a series of delays.[85] The first section of the spire was hoisted to the top of the tower on December 12, 2012,[84][86] and was installed on January 15, 2013.[87] By March 2013, two sections of the spire had been installed. Bad weather delayed the delivery of the final pieces.[88][89]

On May 10, 2013, the final piece of the spire was lifted to the top of One WTC, bringing the tower to its full height of 1,776 feet (541 m), and making it the fourth-tallest building in the world at the time.[90][91] In subsequent months, the exterior elevator shaft was removed; the podium glass, interior decorations, and other finishes were being installed; and installation of concrete flooring and steel fittings was completed.[75] On November 12, 2013, the Height Committee of the Chicago-based Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) made the controversial[92] announcement that One World Trade Center was the tallest building in the United States, declaring that the mast on top of the building is a spire since it is a permanent part of the building's architecture.[93][94] By the same reasoning, the building was also the tallest in the Western Hemisphere.[95]

A report in September 2013 revealed that, at the time of the report, the World Trade Center Association (WTCA) was negotiating with regard to the "World Trade Center" name, as the WTCA had purchased the rights to the name in 1986. The WTCA sought $500,000 worth of free office space in the tower in exchange for the use of "World Trade Center" in the tower's name and associated souvenirs.[96]

Opening and early years

On November 1, 2014, moving trucks started moving items for Condé Nast. The New York Times noted that the area around the World Trade Center had transitioned from a financial area to one with technology firms, residences, and luxury shops, coincident with the building of the new tower.[97] The building opened on November 3, 2014, and Condé Nast employees moved into 24 floors.[98][99][3][100] Condé Nast occupied floors 20 to 44, having completed its move in early 2015.[97] It was expected that the company would attract new tenants to occupy the remaining 40% of unleased space in the tower,[97] as Condé Nast had revitalized Times Square after moving there in 1999.[101] Only about 170 of 3,400 total employees moved into One WTC on the first day. At the time, future tenants included Kids Creative, Legends Hospitality, the BMB Group, Servcorp,[102] and GQ.[101] On November 12, 2014, shortly after the building opened supporting wire rope cables of a suspended working platform slacked, trapping a two-man window washing team.[103][104][105] During the late 2010s, the Durst Organization leased most of the remaining vacant space. The tower reached 92 percent occupancy just before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City in 2020.[106]

By August 2020, Condé Nast indicated it wanted to leave One World Trade Center.[107] This led Advance Publications, parent company of Conde Nast, to start withholding rent payments in January 2021.[108][109] By March 2021, Condé Nast had filed plans to reduce the amount of office space that it leased.[110] After a prolonged impasse, Condé Nast agreed in late 2021 to pay almost $10 million in back rent.[111][112] In December 2021, the New York Liberty Development Corporation announced that it would refinance 1 WTC with a $700 million bond issue. The money from this bond issue would be used to retire the debt from the building's last refinancing in 2012.[113][114] By March 2022, the building was 95 percent leased, a higher percentage than before the COVID-19 pandemic.[115][116] One WTC's vacancy rate was half that of the city as a whole;[117] its high occupancy rate contrasted with that of the original Twin Towers, which had never reached full occupancy until just before the September 11 attacks.[106]

Architecture

Many of Daniel Libeskind's original concepts from the 2002 competition were discarded from the tower's final design. One World Trade Center's final design consisted of simple symmetries and a more traditional profile, intended to compare with selected elements of the contemporary New York skyline. The tower's central spire draws from previous buildings, such as the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building. It also visually resembles the original Twin Towers, rather than being an off-center spire similar to the Statue of Liberty.[118][119][120][121][122] One World Trade Center is considered the first major building whose construction is based upon a three-dimensional Building Information Model.[123]

Just south of the new One World Trade Center is the National September 11 Memorial & Museum, which is located where the original Twin Towers stood. Immediately to the east is World Trade Center Transportation Hub and the new Two World Trade Center site. To the north is 7 World Trade Center, and to the west is Brookfield Place.[124][125][126]

Form and facade

The building occupies a 200-foot (61 m) square, with an area of 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2), nearly identical to the footprints of the original Twin Towers. The tower is built upon a 185-foot (56 m) tall windowless concrete base, designed to protect it from truck bombs and other ground-level attacks.[127] From the 20th floor upwards, the square edges of the tower's cubic base are chamfered back, shaping the building into eight tall isosceles triangles, or an elongated square antiprism.[128] Near its middle, the tower forms a perfect octagon, and then culminates in a glass parapet, whose shape is a square oriented 45 degrees from the base. A 407.9-foot (124.3 m) sculpted mast containing the broadcasting antenna – designed in a collaboration between Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM), artist Kenneth Snelson (who invented the tensegrity structure), lighting designers, and engineers – is secured by a system of cables, and rises from a circular support ring, which contains additional broadcasting and maintenance equipment. At night, an intense beam of light is projected vertically from the spire[13] and shines over 1,000 feet (300 m) above the tower.[129]

David Childs of SOM, the architect of One World Trade Center, said the following regarding the tower's design:[130]

We really wanted our design to be grounded in something that was very real, not just in sculptural sketches. We explored the infrastructural challenges because the proper solution would have to be compelling, not just beautiful. The design does have great sculptural implications, and we fully understand the iconic importance of the tower, but it also has to be a highly efficient building. The discourse about Freedom Tower has often been limited to the symbolic, formal and aesthetic aspects but we recognize that if this building doesn't function well, if people don't want to work and visit there, then we will have failed as architects.[130]

Originally, the base was to be covered in decorative prismatic glass, but a simpler glass-and-steel façade was adopted when the prisms proved unworkable.[51] The current base cladding consists of angled glass fins protruding from stainless steel panels, similar to those on 7 World Trade Center. LED lights behind the panels illuminate the base at night.[131] There are cable-net glass facade panels on all elevations of the building, designed by Schlaich Bergermann, will be consistent with the other buildings in the complex. The facade panels are 60 feet (18 m) high, and range in width from 30 feet (9.1 m) on the east and west sides, 50 feet (15 m) on the north side, and 70 feet (21 m) on the south side.[15] The curtain wall was manufactured and assembled by Benson Industries in Portland, Oregon, using glass made in Minnesota by Viracon.[132]

WSP Group was the lead structural engineer; Jaros, Baum & Bolles (JBB) provided MEP engineering; and Tishman Construction was the main contractor.[133]

Features

One World Trade Center's top floor is officially designated as floor 104,[8] despite the fact that the tower only contains 94 actual stories.[99] The building has 86 usable above-ground floors, of which 78 are intended for office purposes (approximately 2,600,000 square feet (240,000 m2)).[13][134][135] The base consists of floors 1–19, including a 65-foot-high (20 m) public lobby, featuring the 90-foot (27 m) mural ONE: Union of the Senses by American artist José Parlá.[136][137] The lobby also contains two paintings by Donald Martiny, called Lenape and Unami;[138] two paintings by Fritz Bultman, Gravity of Nightfall and Blue Triptych-Intrusion Into the Blue;[139] and two paintings by Doug Argue, Randomly Placed Exact Percentages and Isotropic.[139]

The office floors begin at floor 20 and go up to floor 63.[15] There is a sky lobby on floor 64; designed by Gensler, the sky lobby covers 25,000 square feet (2,300 m2).[140] The space has seating areas, a game room, a meeting room with capacity for 180 people, a cafe, and yoga and fitness classes.[141][140] Seven oil on canvas paintings by artist Greg Goldberg are displayed in the 64th floor sky lobby,[142][143] and Bryan Hunt created a sculpture named Prana, which means "life force" in Sanskrit, on the east side of the 64th floor sky lobby.[139] Office floors resume on floor 65 and stop at floor 90. Floors 91–99 and 103–104 are mechanical floors.[15]

The tenants have access to below-ground parking, storage, and shopping; access to PATH, New York City Subway trains, and the World Financial Center is also provided at the World Trade Center Transportation Hub; Fulton Street/Fulton Center; and Chambers Street–World Trade Center/Park Place/Cortlandt Street stations.[144] The building allows direct access to West Street, Vesey Street, and Fulton Street at ground level.[144] The building has an approximate underground footprint of 42,000 square feet (3,900 m2).[144]

One World Observatory

The tower has a three-story observation deck, located on floors 100–102, in addition to existing broadcast and antenna facilities.[15] Its height is 1,268 feet (386 m), making it the highest vantage point in New York City.[48] Similar to the Empire State Building, visitors to the observation deck and tenants have their own separate entrances; one entrance is on the West Street side of the building, and the other is from within the shopping mall, descending down to a below-ground security screening area.[145] On the observation deck, the actual viewing space is on the 100th floor, but there is a food court on the 101st floor and a space for events for the 102nd floor.[146]

To show visitors the city, and give them information and stories about New York, an interactive tool called City Pulse is used by Tour Ambassadors. The admission fee is $32 per person,[147][148] but admission discounts are available for children and seniors, and the deck is free for 9/11 responders and families of 9/11 victims.[146] When it opened, the deck was expected to have about 3.5 million visitors per year.[149] Tickets went on sale starting on April 8, 2015.[150] The Manhattan District Attorney investigated whether Legends Hospitality had received the contract for the observation deck's operation based on inappropriate political dealings.[151] It officially opened on May 28, 2015,[152][153] one day ahead of schedule.[154]

A plan to build a restaurant near the top of the tower, similar to the original One World Trade Center's Windows on the World, was abandoned as logistically impractical. The tower's window-washing tracks are located on a 16-square-foot area, which is designated as floor 110 as a symbolic reference to the 110 floors of the original tower.[155] There are three eating venues at the top of the building: a café (called One Café); a bar and "small plates" grill (One Mix); and a fine dining restaurant (One Dining). Some commentators, including those for the New York Post and Curbed, have criticized the food prices; the need of a full observatory ticket purchase to enter; and their reputations compared to Windows on the World, the top-floor restaurant in the original One World Trade Center.[156][157]

Sustainability

Like other buildings in the new World Trade Center complex, One World Trade Center includes sustainable architecture features. Much of the building's structure and interior is built from recycled materials, including gypsum boards and ceiling tiles; around 80 percent of the tower's waste products are recycled.[158] Although the roof area of any tower is limited, the building implements a rainwater collection and recycling scheme for its cooling systems. The building's PureCell phosphoric acid fuel cells generate 4.8 megawatts (MW) of power, and its waste steam generates electricity.[159] The New York Power Authority selected UTC Power to provide the tower's fuel cell system, which was one of the largest fuel cell installations in the world once completed.[160] The tower also makes use of off-site hydroelectric and wind power.[161] The windows are made of an ultra-clear glass, which allows maximum sunlight to pass through; the interior lighting is equipped with dimmers that automatically dim the lights on sunny days, reducing energy costs.[129] Like all of the new facilities at the World Trade Center site, One World Trade Center is heated by steam, with limited oil or natural gas utilities on-site.[162] One World Trade Center received a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Gold Certification, making it one of the most environmentally sustainable skyscrapers in the world.[163]

Security features

Along with the protection provided by the reinforced concrete base, a number of other safety features were included in the building's design, so that it would be prepared for a major accident or terrorist attack. Like 7 World Trade Center, the building has 3-foot (91 cm) thick reinforced concrete walls in all stairwells, elevator shafts, risers, and sprinkler systems. There are also extra-wide, pressurized stairwells, along with a dedicated set of stairwells exclusively for the use of firefighters, and biological and chemical filters throughout the ventilation system.[129][164] In comparison, the original Twin Towers used a purely steel central core to house utility functions, protected only by lightweight drywall panels.[165]

The building is no longer 25 feet (8 m) away from West Street, as the Twin Towers were; at its closest point, West Street is 65 feet (20 m) away.[129] The Port Authority has stated: "Its structure is designed around a strong, redundant steel moment frame consisting of beams and columns connected by a combination of welding and bolting. Paired with a concrete-core shear wall, the moment frame lends substantial rigidity and redundancy to the overall building structure while providing column-free interior spans for maximum flexibility."[164]

In addition to safety design, new security measures were implemented. All vehicles will be screened for radioactive materials and other potentially dangerous objects before they enter the site through the underground road. Four hundred closed-circuit surveillance cameras will be placed in and around the site, with live camera feeds being continuously monitored by the NYPD. A computer system will use video-analytic computer software, designed to detect potential threats, such as unattended bags, and retrieve images based on descriptions of terrorists or other criminal suspects. New York City and Port Authority police will patrol the site.[166]

Before the World Trade Center site was fully completed, the plaza was not completely opened to the public, as the original World Trade Center plaza was.[167] The initial stage of the opening process began on Thursday, May 15, 2014, when the "Interim Operating Period" of the National September 11 Memorial ended. During this period, all visitors were required to undergo airport style security screening as part of the "Interim Operating Period", which was expected to end on December 31, 2013.[168] Screening did not fully end until the official dedication and opening of the museum[169][170] on May 21, 2014, after which visitors were allowed to use the plaza without needing passes.[167]

Design evolution

.jpg.webp)

The original design went through significant changes after the Durst Organization joined the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey as the project's co-developer in 2010.[118]

The 185-foot (56 m) tall base corners were originally designed to gently slope upward and have prismatic glass.[118][121] The corners were later squared. In addition, the base's walls are now covered in "hundreds of pairs of 13-foot [4.0 m] vertical glass fins set against horizontal bands of eight-inch-wide [20 cm] stainless-steel slats."[118][121]

The spire was originally to be enclosed with a protective radome, described as a "sculptural sheath of interlocking fiberglass panels".[118][119][120] The radome-enclosed spire was then changed to a plain antenna.[118] Douglas Durst, the chairman of the Durst Organization, stated that the design change would save $20 million.[120][171] SOM strongly criticized the change, and Childs said: "Eliminating this integral part of the building's design and leaving an exposed antenna and equipment is unfortunate ... We stand ready to work with the Port on an alternate design."[120] After joining the project in 2010, the Durst Organization had suggested eliminating the radome to reduce costs, but the proposal was rejected by the Port Authority's then-executive director, Christopher O. Ward.[120] Ward was replaced by Patrick Foye in September 2011.[119] Foye changed the Port Authority's position, and the radome was removed from the plans. In 2012, Douglas Durst gave a statement regarding the final decision: "(the antenna) is going to be mounted on the building over the summer. There's no way to do anything at this point."[120]

The large triangular plaza on the west side of One World Trade Center was originally planned to have stainless steel steps descending to West Street, but the steps were changed to a terrace in the final design. The terrace can be accessed through a staircase on Vesey Street. The terrace is paved in granite, and has 12 sweetgum trees, in addition to a block-long planter/bench.[118]

Durst also removed a skylight from the plaza's plans; the skylight was designed to allow natural light to enter the below-ground observation deck lobby.[118] The plaza is 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m) higher than the adjacent sidewalk.[118]

The Port Authority formally approved all these revisions, and the revisions were first reported by the New York Post.[172] Patrick Foye, the executive director of the Port Authority, said that he thought that the changes were "few and minor" in a telephone interview.[118]

A contract negotiated between the Port Authority and the Durst Organization states that the Durst Organization will receive a $15 million fee and a percentage of "base building changes that result in net economic benefit to the project." The specifics of the signed contract give Durst 75% of the savings (up to $24 million) with further returns going down to 50%; 25%; and 15% as the savings increase.[118]

Height

_April_2016_(27509488345).jpg.webp)

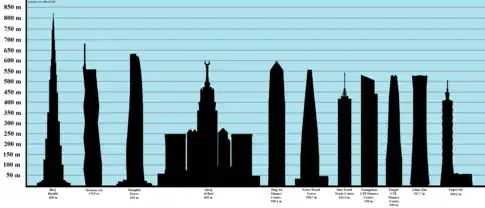

The top floor of One World Trade Center is 1,368 feet (417 m) above ground level, along with a 33 ft 4 in (10.16 m) parapet; this is identical to the roof height of the original One World Trade Center.[173] The tower's spire brings it to a pinnacle height of 1,776 feet (541 m),[8][174] a figure intended to symbolize the year 1776, when the United States Declaration of Independence was signed.[13][175][176][177] When the spire is included in the building's height, as stated by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH), One World Trade Center surpasses the height of Taipei 101 (1,671-foot (509 m)), is the world's tallest all-office building, and the seventh-tallest skyscraper in the world as of May 2023, behind the Burj Khalifa,[178] Merdeka 118, Shanghai Tower,[179] Abraj Al Bait,[180] Ping An Finance Centre and Lotte World Tower.[181]

One World Trade Center is the second-tallest freestanding structure in the Western Hemisphere, as the CN Tower in Toronto exceeds One World Trade Center's pinnacle height by approximately 40 ft (12.2 m).[182] The Chicago Spire, with a planned height of 2,000 feet (610 m), was expected to exceed the height of One World Trade Center, but its construction was canceled due to financial difficulties in 2009.[183]

After design changes for One World Trade Center's spire were revealed in May 2012, there were questions as to whether the 407.9-foot (124.3 m)-tall structure would still qualify as a spire, and thus be included in the building's height.[184][185] Since the tower's spire is not enclosed in a radome as originally planned, it could be classified as a simple antenna, which is not included in a building's height, according to the CTBUH.[185] Without the spire, One World Trade Center would be 1,368 feet (417 m) tall, making it the seventh-tallest building in the United States, behind the Trump International Hotel & Tower in Chicago.[186][187]

Upon completion, the building became the tallest in New York City with the antenna, but its roof was surpassed in 2015 by 432 Park Avenue, which topped out at 1,396 feet (426 m) high.[188][189][190] One World Trade Center's developers had disputed the claim that the spire should be reclassified as an antenna following the redesign,[191] with Port Authority spokesman Steve Coleman reiterating that "One World Trade Center will be the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere."[184]

In 2012, the CTBUH announced that it would wait to make its final decision as to whether or not the redesigned spire would count towards the building's height.[184] On November 12, 2013, the CTBUH announced that One World Trade Center's spire would count as part of the building's recognized height, giving it a final height of 1,776 feet (541 m), and making it the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere.[93]

Incidents

In September 2013, three BASE jumpers parachuted off the then-under-construction tower. The three men and one accomplice on the ground surrendered to authorities in March 2014.[192] They were convicted of several misdemeanors in June 2015[193] and sentenced to community service and a fine.[194][195]

In March 2014, tower security was breached by 16-year-old Weehawken, New Jersey resident Justin Casquejo, who entered the site through a hole in a fence. He was arrested on trespassing charges.[196] He allegedly dressed like a construction worker, sneaked in, and convinced an elevator operator to lift him to the tower's 88th floor, according to news sources. He then used stairways to get to the 104th floor, walked past a sleeping security guard, and climbed up a ladder to get to the antenna, where he took pictures for two hours.[197] The elevator operator was reassigned, and the guard was fired.[198][199] It was then revealed that officials had failed to install security cameras in the tower, which facilitated Casquejo's entry to the site.[200][201] Casquejo was sentenced to 23 days of community service as a result.[202]

Reception

The social center of the previous One World Trade Center included a restaurant on the 107th floor, called Windows on the World, and The Greatest Bar on Earth; these were tourist attractions in their own right, and a gathering spot for people who worked in the towers.[203][204] This restaurant also housed one of the most prestigious wine schools in the United States, called "Windows on the World Wine School", run by wine personality Kevin Zraly.[205] Despite numerous assurances that these attractions would be rebuilt,[206] the Port Authority scrapped plans to rebuild them, which has outraged some observers.[207]

The fortified base of the tower has also been a source of controversy. Some critics, including Deroy Murdock of the National Review,[208] have said that it is alienating and dull, and reflects a sense of fear rather than freedom, leading them to dub the building "the Fear Tower".[209] Nicolai Ouroussoff, the architecture critic for The New York Times, calls the tower base a "grotesque attempt to disguise its underlying paranoia".[210]

Owners and tenants

One World Trade Center is principally owned by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Around 5 percent equity of the building was sold to the Durst Organization, a private real estate company, in exchange for an investment of at least $100 million. The Durst Organization assisted in supervising the building's construction, and manages the building for the Port Authority, having responsibility for leasing, property management, and tenant installations.[211][212] By September 2012, around 55 percent of the building's floor space had been leased,[213] but no new leases were signed for three years until May 2014;[214] the amount of space leased had gone up to 62.8 percent by November 2014.[215]

In 2006, the State of New York agreed to a 15-year 415,000 square feet (38,600 m2) lease, with an option to extend the lease's term and occupy up to 1,000,000 square feet (90,000 m2).[216] The General Services Administration (GSA) initially agreed to a lease of around 645,000 square feet (59,900 m2),[162][216] and New York State's Office of General Services (OGS) planned to occupy around 412,000 square feet (38,300 m2). However, the GSA ceded most of its floor space to the Port Authority in July 2011, and the OGS withdrew from the lease contract.[217] In April 2008, the Port Authority announced that it was seeking a bidder to operate the 18,000 sq ft (1,700 m2) observation deck on the tower's 102nd floor;[218] in 2013, Legends Hospitality Management agreed to operate the observatory in a 15-year, $875 million contract.[219]

The building's first lease, a joint project between the Port Authority and Beijing-based Vantone Industrial, was announced on March 28, 2009. A 190,810 sq ft (17,727 m2) "China Center", combining business and cultural facilities, that would be planned between floors 64 and 69; it is intended to represent Chinese business and cultural links to the United States, and to serve American companies that wish to conduct business in China.[213] Vantone Industrial's lease is for 20 years and 9 months.[220] In April 2011, a new interior design for the China Center was unveiled, featuring a vertical "Folding Garden", based on a proposal by the Chinese artist Zhou Wei.[221] In September 2015, China Center agreed to reduce the leased space to a single floor.[222]

On August 3, 2010, Condé Nast Publications signed a tentative agreement to move the headquarters and offices for its magazines into One World Trade Center, occupying up to 1,000,000 square feet (90,000 m2) of floor space.[223] On May 17, 2011, Condé Nast reached a final agreement with the Port Authority, securing a 25-year lease with an estimated value of $2 billion.[69][224] On May 25, 2011, Condé Nast finalized the lease contract, obtaining 1,008,012 square feet (93,647.4 m2) of office space between floors 20–41 and 30,000 square feet (2,800 m2) of usable space in the podium and below grade floors.[70] Condé Nast leased 133,000 square feet (10,000 m2) of space on floors 42 to 44 in January 2012.[225] In the late 2010s and early 2020s, Condé Nast subleased some of its space to other companies. This included Ambac Financial Group in March 2019;[226][227] Ennead Architects in April 2019;[228][229] and Constellation Agency and Reddit in 2021.[230][231]

In August 2014, it was announced Servcorp signed a 15-year lease for 34,775 square feet (3,230.7 m2), taking the entire 85th floor.[232] Servcorp subsequently subleased all of its space on the 85th floor as private offices, boardrooms and co-working space to numerous medium-sized businesses such as ThinkCode, D100 Radio, and Chérie L'Atelier des Fleurs.[233][234]

Key figures

Developer

Larry Silverstein of Silverstein Properties, the leaseholder and developer of the complex, retains control of the surrounding buildings, while the Port Authority has full control of the tower itself. Silverstein signed a 99-year lease for the World Trade Center site in July 2001, and remains actively involved in most aspects of the site's redevelopment process.[235]

Before construction of the new tower began, Silverstein was involved in an insurance dispute regarding the tower. The terms of the lease agreement signed in 2001, for which Silverstein paid $14 million,[236] gave Silverstein, as leaseholder, the right and obligation to rebuild the structures if they were destroyed.[237] After the September 11 attacks, there were a series of disputes between Silverstein and insurance companies concerning the insurance policies that covered the original towers; this resulted in the construction of One World Trade Center being delayed. After a trial, a verdict was rendered on April 29, 2004. The verdict was that ten of the insurers involved in the dispute were subject to the "one occurrence" interpretation, so their liability was limited to the face value of those policies. Three insurers were added to the second trial group.[238][239] At that time, the jury was unable to reach a verdict on one insurer, Swiss Reinsurance, but it did so several days later on May 3, 2004, finding that this company was also subject to the "one occurrence" interpretation.[240] Silverstein appealed the Swiss Reinsurance decision, but the appeal failed on October 19, 2006.[241] The second trial resulted in a verdict on December 6, 2004. The jury determined that nine insurers were subject to the "two occurrences" interpretation, referring to the fact that two different planes had destroyed the towers during the September 11 attacks. They were therefore liable for a maximum of double the face value of those particular policies ($2.2 billion).[242] The highest potential payout was $4.577 billion, for buildings 1, 2, 4, and 5.[243]

In March 2007, Silverstein appeared at a rally of construction workers and public officials outside an insurance industry conference. He highlighted what he described as the failures of insurers Allianz and Royal & Sun Alliance to pay $800 million in claims related to the attacks. Insurers state that an agreement to split payments between Silverstein and the Port Authority is a cause for concern.[244]

Key project coordinators

David Childs, one of Silverstein's favorite architects, joined the project after being urged by him. Childs developed a design for One World Trade Center, initially collaborating with Daniel Libeskind. In May 2005, Childs revised the design to address security concerns. He is the architect of the tower, and is responsible for overseeing its day-to-day design and development.[245]

Architect Daniel Libeskind won the invitational competition to develop a plan for the new tower in 2002. He gave a proposal, which he called "Memory Foundations", for the design of One World Trade Center. His design included aerial gardens, windmills, and off-center spire.[122] Libeskind later denied a request to place the tower in a more rentable location next to the PATH station. He instead placed it another block west, as it would then line up with, and resemble, the Statue of Liberty.[246] Most of Libeskind's original designs were later scrapped, and other architects were chosen to design the other WTC buildings.[note 2] However, one element of Libeskind's initial plan was included in the final design – the tower's symbolic height of 1,776 feet (541 m).[247]

Daniel R. Tishman – along with his father John Tishman, builder of the original World Trade Center – led the construction team from Tishman Realty & Construction, the selected builder for One World Trade Center.[248][249]

Douglas and Jody Durst, the co-presidents of the Durst Organization, a real estate development company, won the right to invest at least $100 million in the project on July 7, 2010.[250]

In August 2010, Condé Nast, a long-time Durst tenant, confirmed a tentative deal to move into One World Trade Center,[251][252][253] and finalized the deal on May 26, 2011.[254] The contract negotiated between the Port Authority and the Durst Organization specifies that the Durst Organization will receive a $15 million fee, and a percentage of "base building changes that result in net economic benefit to the project". The specifics of the signed contract give Durst 75 percent of savings up to $24 million, stepping down to 50, 25, and 15 percent as savings increase.[118] Since Durst joined the project, significant changes have been made to the building, including the 185-foot (56 m) base of the tower, the spire, and the plaza to the west of the building, facing the Hudson River. The Port Authority has approved all the revisions.[118]

Port Authority construction workers

A WoodSearch Films short-subject documentary entitled How does it feel to work on One World Trade Center? was uploaded to YouTube on August 31, 2010. It depicted construction workers who were satisfied with the working conditions at the construction site.[255] However, further analysis of the work site showed that dozens of construction-related injuries had occurred at the site during the construction of One World Trade Center, including 34 not reported to the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.[256]

Workers left post-9/11-related graffiti at the site, which are meant to symbolize rebirth and resilience.[257]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The older name still is used in popular culture.

- ↑ Foster and Partners was chosen for 2 WTC, Richard Rogers was chosen for 3 WTC, Fumihiko Maki and associates was chosen for 4 WTC, Kohn Pedersen Fox was chosen for 5 WTC.

References

- 1 2 Westfeldt, Amy (March 26, 2009). "Freedom Tower has a new preferred name". Silverstein Properties. Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 31, 2009. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ↑ Stanglin, Doug (May 10, 2013). "Spire permanently installed on WTC tower". USA Today. Gannett Company. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- 1 2 Moore, Jack (November 3, 2014). "World Trade Center Re-opens as Tallest Building in America". International Business Times. One World Trade Center. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- 1 2 Smith, Aaron (November 3, 2014). "One World Trade Center, the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere, is open for business". money.cnn.com. CNN Money. Archived from the original on January 18, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- 1 2 "One World Trade Center Observatory Opens to Public". usnews.com. U.S. News. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- 1 2 Brennan, Morgan (April 30, 2012). "1 World Trade Center Officially New York's New Tallest Building". Forbes. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Brown, Eliot (January 30, 2012). "Tower Rises, And So Does Its Price Tag". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "One World Trade Center – The Skyscraper Center". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. September 11, 2015. Archived from the original on May 7, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "One World Trade Center". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ↑ "One World Trade Center to retake title of NYC's tallest building". Fox News. Associated Press. April 29, 2012. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Office Leasing". One World Trade Center. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Elevating One World Trade Center". ThyssenKrupp Elevator. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "One World Trade Center". WTC.com. Silverstein Properties. September 16, 2015. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "The Louis Berger Group and Hill International to Provide Program Management Services for Downtown Restoration Program and WTC Transportation Hub". Hill International, Inc. August 13, 2004. Archived from the original on March 31, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "One World Trade Center". SkyscraperPage.. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- ↑ "Port Authority And Vantone Industrial Sign First Lease For One World Trade Center (The Freedom Tower)". PANYNJ.gov (Press release). March 26, 2009. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ↑ "Freedom Tower Will Be Called One World Trade Center". FoxNews.com. March 26, 2009. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ↑ Feiden, Douglas (March 27, 2009). "'Freedom' out at WTC: Port Authority says The Freedom Tower is now 1 World Trade Center". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ↑ Gillespie, Angus K. (1999). "Chapter 1". Twin Towers: The Life of New York City's World Trade Center. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-7838-9785-5.

- ↑ Wright, George Cable (January 23, 1962). "2 States Agree on Hudson Tubes and Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times.

- ↑ National Construction Safety Team (September 2005). "Chapter 1" (PDF). Final Report on the Collapse of the World Trade Center Towers. NIST. pp. 5–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 28, 2005.

- ↑ Taylor, R. E. (December 1966). "Computers and the Design of the World Trade Center". Journal of the Structural Division. 92 (ST–6): 75–91. doi:10.1061/JSDEAG.0001571.

- ↑ "Timeline: World Trade Center chronology". PBS – American Experience. Archived from the original on August 25, 2003. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- ↑ "1973: World Trade Center Is Dynamic Duo of Height". Engineering News-Record. August 16, 1999. Archived from the original on June 11, 2002.

- ↑ Ruchelman, Leonard I. (1977). The World Trade Center: Politics and Policies of Skyscraper Development. Syracuse University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-81562-180-5.

- ↑ Lew, H.S.; Bukowski, Richard W.; Carino, Nicholas J. (September 2005). Design, Construction, and Maintenance of Structural and Life Safety Systems (NCSTAR 1-1). National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. xxxvi. Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ↑ Darton, Eric (1999) Divided We Stand: A Biography of New York's World Trade Center, Chapter 6, Basic Books.

- ↑ Mcdowell, Edwin (April 11, 1997). "At Trade Center Deck, Views Are Lofty, as Are the Prices". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- 1 2 Holusha, John (January 6, 2002). "Commercial Property; In Office Market, a Time of Uncertainty". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- 1 2 "Ford recounts details of Sept. 11". Real Estate Weekly. BNET. February 27, 2002. Archived from the original on March 26, 2010. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ↑ Lew, H.S.; Bukowski, Richard W.; Carino, Nicholas J. (September 2005). Design, Construction, and Maintenance of Structural and Life Safety Systems (NCSTAR 1-1). National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). p. 13. Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ↑ "Seven World Trade Center (pre-9/11)". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2006. Retrieved May 7, 2006.

- ↑ Yoneda, Yuka (September 11, 2011). "6 Important Facts You May Not Know About One World Trade Center". Inhabitat. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Flight Path Study – American Airlines Flight 11" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. February 19, 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 14, 2007. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Flight Path Study – United Airlines Flight 175" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. February 19, 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 17, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ↑ "9/11 Commission Report". The National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ↑ Miller, Bill (May 1, 2002). "Skyscraper Protection Might Not Be Feasible, Federal Engineers Say". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ↑ World Trade Center Building Performance Study, Ch. 5 WTC 7 – section 5.5.4

- ↑ Final Report on the Collapse of World Trade Center Building 7, p. xxxvii.

- ↑ "How much did the September 11 terrorist attack cost America?". 2004. Institute for the Analysis of Global Security. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Winnipegger heads to NY for 9/11 memorial". CBC News. September 9, 2011. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

A total of 2,996 people died: 19 hijackers and 2,977 victims.

- ↑ Stone, Andrea (August 20, 2002). "Military's aid and comfort ease 9/11 survivors' burden". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 27, 2012. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- 1 2 Sunder (2005), p. 48.

- ↑ Westfeldt, Amy (March 23, 2007). "Debate over staircase slows WTC project". Times Union. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Lower Manhattan Development Corporation Announces Design Study for World Trade Center Site and Surrounding Areas" (Press release). RenewNYC.org. August 14, 2002. Archived from the original on August 25, 2008. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ↑ Walsh, Edward (September 15, 2001). "Bush Encourages N.Y. Rescuers" (PDF). The Washington Post. pp. A10. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 24, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ↑ "Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People". The White House. September 20, 2001. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dupré, Judith (2016). One World Trade Center: Biography of the Building (1st ed.). New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-33631-4. OCLC 871319123. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ↑ "Freedom Tower's Evolution". The New York Times. January 3, 2006. Archived from the original on October 29, 2011. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ↑ "America's Freedom Tower?". NBC News. February 17, 2005. Archived from the original on October 1, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Prismatic glass façade for WTC tower scrapped" Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The Huffington Post. May 12, 2011. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ↑ "Final design for Freedom Tower is unveiled". Civil + Structural Engineer. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Trucks roll to begin Freedom Tower construction". Daily News. New York. April 27, 2006. Archived from the original on May 3, 2006.

- 1 2 Cooper, Michael (March 16, 2006). "Stalled Talks Are More Bad News for Pataki". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Governor Pataki, Governor Mcgreevey, Mayor Bloomberg Lay Cornerstone for Freedom Tower". PANYNJ.gov (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. July 4, 2004. Archived from the original on September 27, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Cornerstone of Freedom Tower removed". CBS News. June 25, 2006. Archived from the original on January 8, 2007.

- ↑ "One World Trade Center". FRASER: Building His District, Brick by Brick. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Building of N.Y. Freedom Tower begins". USA Today. Associated Press. April 28, 2006. Archived from the original on March 31, 2009. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ↑ Chan, Sewell (December 18, 2006). "Messages of Love and Hope on a Freedom Tower Beam". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ↑ "First Freedom Tower Beam Rises At Ground Zero". WCBS-TV. December 19, 2006. Archived from the original on December 20, 2006. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- 1 2 "Statement by Port Authority Regarding Preparation of Towers 3 and 4 Bathtub at WTC Site to Allow Silverstein Properties to Begin Construction in January" (Press release). Port Authority of New York & New Jersey. December 31, 2007. Archived from the original on September 16, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- 1 2 Nordenson, Guy (February 16, 2007). "Freedom From Fear". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 5, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ↑ "World Trade Center project has begun to take shape". The Star-Ledger. May 6, 2010. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Strunsky, Steve (May 18, 2010). "Port Authority installs cocoon safety system around World Trade Center steel structure". The Star-Ledger. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ "1 WTC, aka Freedom Tower, reaches halfway mark". The Wall Street Journal. Associated Press. December 16, 2010. Archived from the original on December 21, 2010.

- ↑ "World Trade Center Growing This Summer". PANYNJ.gov. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. 2011. Archived from the original on October 23, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ↑ "The World Trade Centre Slow building". The Economist. April 23, 2009. Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- ↑ "'Freedom' out at WTC: Port Authority says The Freedom Tower is now 1 World Trade Center". Daily News. New York. March 27, 2009. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- 1 2 Bagli, Charles V. (May 17, 2011). "Condé Nast Will Be Anchor of 1 World Trade Center". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- 1 2 "One World Trade Center lands lease with Conde Nast". Reuters. May 25, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ↑ "One World Trade Center". PANYNJ.gov. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ "World Trade Center design flaw could cost millions". The Wall Street Journal. Associated Press. February 1, 2012. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ↑ "1 World Trade Center Adds Another Prime Tenant, A Law Firm". The New York Times. January 27, 2012. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ↑ "Chadbourne & Parke Will Not Lease at One World Trade" Archived November 5, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. The Real Deal. March 20, 2012. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- 1 2 "One World Trade Center construction updates". Lower Manhattan.info. February 14, 2014. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- 1 2 Brown, Eliot (March 30, 2012). "One World Trade Center Hits 100 Stories, Helped by Funny Math". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ↑ Bagli, Charles V. (February 13, 2007). "Spitzer, in Reversal, Is Expected to Approve Freedom Tower, Officials Say". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 23, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Critics blast Port Authority for changing position on how toll hike money will be spent". The Star-Ledger. November 30, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2012

- ↑ "It's official: 1 WTC is New York's new tallest building". Daily News. New York. April 30, 2012. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- ↑ "One World Trade Center On Top As Tallest Building In New York City". International Business Times. April 30, 2012. Archived from the original on June 26, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Poppy Harlow; George Lerner; Jason Hanna (June 15, 2012). "Obama signs beam of One World Trade Center". CNN. Archived from the original on June 15, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ↑ Brown, Eliot (April 11, 2012). "With New Logo, 1 WTC Begins Marketing Push". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Higgs, Larry (August 30, 2012). "One World Trade Center steel skeleton completed". Asbury Park Press. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- 1 2 "Steel spire rises atop New York's One World Trade Center". Reuters. December 12, 2012. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- 1 2 Edmiston, Jake (May 2, 2013). "'A historic milestone': 125-metre spire from Quebec crowns World Trade Centre in N.Y.C after dispute solved". National Post. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ↑ Mathias, Christopher (December 12, 2012). "One World Trade Center Spire: Workers Begin To Hoist Spire Atop City's Tallest Building". The Huffington Post. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ↑ "First section of spire installed at One World Trade Center" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. January 15, 2013. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- ↑ "1 World Trade Center to top out Monday as tallest building in hemisphere". CNN. April 28, 2013. Archived from the original on April 28, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Weather postpones trade center's ascent to tallest". The Plain Dealer. April 29, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ "Crews Permanently Install Spire On Top Of One World Trade Center". CBS News. May 10, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ "Final pieces hoisted atop One World Trade Center". CNN. May 3, 2013. Archived from the original on May 3, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ↑ "Tallest building ruling: Willis Tower loses to One World Trade Center". Chicago Tribune. November 12, 2013. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- 1 2 "Architects rule 1 World Trade Center tallest building in US". MyFoxNY. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ↑ "CTBUH Affirms One World Trade Center Height". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. November 12, 2013. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ↑ DeGregory, Priscilla (November 3, 2014). "1 World Trade Center is open for business". New York Post. Archived from the original on November 13, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ↑ Simone Foxman (September 13, 2013). "The puzzling non-profit behind the "World Trade Center" name makes a surprising amount of money". Quartz. Archived from the original on September 13, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Bagli, Charles V. (November 2, 2014). "Condé Nast Moves Into the World Trade Center as Lower Manhattan Is Remade". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ Dawsey, Josh (October 23, 2014). "One World Trade to Open Nov. 3, But Ceremony is TBD". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- 1 2 Margolin, Josh (November 3, 2014). "1 World Trade Center Opening Highlights Rebirth, Renewal Following 9/11 Attacks". ABC News. Archived from the original on August 25, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2018.

- ↑ "One World Trade Center to become NYC's tallest building". WJLA-TV. Associated Press. April 30, 2012. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- 1 2 Morris, Keiko (November 2, 2014). "Finally, Tenants at One World Trade Center". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ "World Trade Center opens for business". USA Today. Associated Press. November 3, 2014. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ "They train for this: Crews rescue World Trade Center window washers". CNN. November 12, 2014. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ "2 workers rescued from 69th-floor scaffold at One WTC". USA Today. November 12, 2014. Archived from the original on November 13, 2014. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ Santoro, Marc (November 12, 2014). "Peril, and Daring, at 1 World Trade Center as Window Washers Are Trapped". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 13, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- 1 2 "Shared amenities and public space may help usher the World Trade Center office complex into a brighter future". The Architect's Newspaper. September 9, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ↑ "Condé Nast Facing Pushback As It Tries To Exit 1WTC". The Real Deal New York. August 6, 2020. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ↑ "Condé Nast Withholding Rent At One World Trade Center". The Real Deal New York. February 9, 2021. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ↑ Berger, Paul (February 9, 2021). "Condé Nast Withholds $2.4 Million in Rent at One World Trade". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ↑ Coen, Andrew (March 10, 2021). "The Future of 1 World Trade Center Is Up in the Air". Commercial Observer. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ↑ Young, Celia (August 5, 2021). "Durst Settles 1 WTC Rent With Condé Nast, Targets Landmark Theatres". Commercial Observer. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ↑ "Conde Nast settles its overdue rent at 1 WTC". Real Estate Weekly. August 3, 2021. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ↑ "1 WTC Set for Refi New York Liberty Development Corporation". The Real Deal New York. December 3, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ↑ Young, Celia (December 3, 2021). "State Agency Planning $700M Refinance of 1 WTC". Commercial Observer. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ↑ Hallum, Mark (March 29, 2022). "One World Trade Center 95 Percent Leased With Latest Deal: Durst". Commercial Observer. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ↑ "One World Trade Center now 95% leased". Real Estate Weekly. March 30, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ↑ Hu, Winnie (December 13, 2022). "Why One World Trade Is Winning R.T.O." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 David W. Dunlap (June 12, 2012). "1 World Trade Center Is a Growing Presence, and a Changed One". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Transportation Nation: "Patrick Foye Named New Executive Director of NY-NJ Port Authority" By Jim O'Grady Archived April 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. October 19, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Eliot Brown (May 10, 2012). "Pointed Spat Over World Trade Spire". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Steve Cuozzo (May 24, 2012). "World Trade Center offers warm welcome". New York Post. Archived from the original on March 17, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- 1 2 "Refined Master Site Plan for the World Trade Center Site". Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ Frangos, Alex (July 7, 2004). "New Dimensions in Design". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Design Overview". 9/11 Memorial. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ↑ Handwerker, Haim (November 20, 2007). "The politics of remembering Ground Zero – Haaretz – Israel News". Haaretz. Archived from the original on November 22, 2007.

- ↑ Herzenberg, Michael (September 7, 2011). "Mayor, WTC Developer Say Trade Center Site Has New Lease On Life". NY1. Archived from the original on September 21, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ "New York beefs up World Trade Center site security for September 11 10th anniversary" Archived April 15, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The Telegraph. August 8, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- ↑ "The Freedom Tower: World Trade Center, New York". Glass Steel and Stone. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "SOM Freedom Tower Fact Sheet" (PDF) (Press release). Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. June 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 3, 2005.

- 1 2 Interview with David Childs (cont'd). Retrieved October 12, 2007

- ↑ "New glass design for One World Trade Center base wins approval" Archived February 28, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. WTC.com, November 15, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Curtain Wall Installation Begins at One World Trade Center" (Press release). Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP. November 16, 2010. Archived from the original on December 14, 2010. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- ↑ "One World Trade Center - The Skyscraper Center". www.skyscrapercenter.com. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ↑ "World Trade Centre Behind Schedule And Over Budget Says New York Governor". Sky News. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ↑ Barrionuevo, Alexei (July 26, 2005). "In Chicago, Plans for a High-Rise Raise Interest and Post-9/11 Security Concerns". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Art fit for a skyscraper". The Economist. New York. November 6, 2014. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ↑ Munro, Cait (November 21, 2014). "Is José Parlá's Mural at One World Trade Center the World's Largest Welcome Mat?". Artnet News. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ↑ "A Chapel Hill Artist Paints His Way Into The World Trade Center". WUNC. October 30, 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- 1 2 3 "New York's 1 World Trade Center tower boasts large-scale, bold art". New York Daily News. Associated Press. December 11, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- 1 2 Cullen, Terence (October 19, 2016). "A Look Inside 1 WTC's 'Piazza' in the Sky". Commercial Observer. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- ↑ Plitt, Amy (October 21, 2016). "One World Trade Center will get a 'sky lobby' designed by Gensler". Curbed NY. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- ↑ Duray, Dan (March 17, 2015). "Greg Goldberg on His Sky Lobby Paintings at One World Trade Center". artnews.com. Art News. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ↑ "Unity Through Abstraction: One World Trade Center's Inaugural Art Collection". artsy.net. Artsy. February 24, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "One World Trade Center – Fact Sheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- ↑ "The World Trade Center Retail Floor Plans (Part 2)". Tribeca Citizen. January 16, 2014. Archived from the original on January 17, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- 1 2 "Observatory at 1 World Trade Center opens to public May 29". Crain's New York. Associated Press. April 8, 2015. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ↑ Chung, Jen (October 28, 2014). "One World Trade Center Observatory Sets Admission At $32". gothamist. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ↑ "One World Observatory". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on May 22, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ↑ Gelfand, Eric (February 25, 2014). "One World Observatory Launches". Legends.net. Archived from the original on May 22, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ↑ "One WTC observation deck tickets go on sale, will open in May". NY Business Journal. April 8, 2015. Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Prosecutors subpoenas NY-NJ agency records on World Trade Center deal". Reuters. April 9, 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- ↑ "New World Trade Centre observatory opens, banishing memories of the Twin Towers". The Telegraph. May 28, 2015. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ↑ "Observatory At One World Trade Center Opens To Public Friday". CBS Local. May 28, 2015. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ↑ Corky Siemaszko (April 7, 2015). "Observation deck at World Trade Center's Freedom Tower to open May 29". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ↑ Blaszczak, Karl (September 19, 2013). "The Technology Behind One World Trade Center". Scribol. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ↑ "WTF 1 WTC! It's $32 just to walk into your restaurant?". New York Post. April 15, 2015. Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ↑ Alberts, Hana R. (July 1, 2015). "Don't Eat at One World Trade Center's Sky-High Restaurants". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on August 13, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2015.