| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 7,000–45,000[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Warsaw and other major population centers | |

| Languages | |

| Armenian and Polish | |

| Religion | |

| Armenian Apostolic Church, Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Armenians in Slovakia, Armenians in the Czech Republic |

| Part of a series on |

| Armenians |

|---|

|

| Armenian culture |

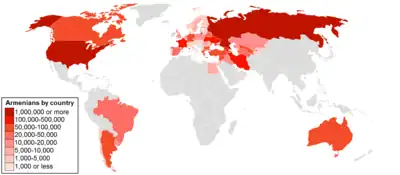

| By country or region |

Armenian diaspora Russia |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

|

| Persecution |

Armenians in Poland (Armenian: Հայերը Լեհաստանում, romanized: Hayery Lehastanum; Polish: Ormianie w Polsce) have an important and historical presence going back to the 14th century.[3] According to the Polish census of 2021 there are 6,772 ethnic Armenians in Poland.[1]

History

Origins

About the beginning of the Armenian presence in Poland, Adolf Nowaczyński, a Polish writer, gives us the following sketch of the Armenians of Poland:

Long before the fall of the (Armenian) Kingdom of Cilicia in 1375, the Armenians appeared in Poland, having been invited here by David Igorevich, the Prince of Galicia.

The first dismemberment of their country brought about a great emigration. The Armenian emigrants, taking with them a handful of native soil in a piece of cloth, were scattered in southern Russia, into the Caucasus, in the land of the Cossacks, while 50,000 from among them came to Poland. From then on, new streams of Armenian emigration periodically proceeded from the shores of Pontus towards the hospitable country of the Sarmatians, and it must be said that these guests, coming from such a distance, proved themselves really 'the salt of the earth,' an exceedingly useful and desirable element. They settled mostly in the cities, and in many places they became the nucleus of the Polish bourgeois class.

Ties to Lwów

The city of Lwów, (now Lviv), the most patriotic center of Poland, then the theater of so many historic turmoils, owes its luster in large degree to Armenian immigrants. Kamieniec-Podolski (Kamianets-Podilskyi), that crown of Polish old fortresses, received its fame from the Armenians who settled there. Fleeing from Crimea, they were invited to settle in Jazłowiec, where they founded the church of the Holy Mother of God, now dedicated to Saint Nicholas of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.[4] In Bukowina and in all Galicia, the Armenian element plays a role of the first order in political and social life, in industry and in intellectual movement. Finally, in Poland proper and its capital, Warsaw, the descendants of those who once were the great nation on the Arax, rendered themselves illustrious in all careers. In the battles of Grunwald and Varna, the forebears of the Alexandrovics, the Augustinovics, the Agopsovics and Apakanovics took part. Also from their ranks came forth later renowned Poles, such as the Malowski, Missasowicz, Piramowicz, Pernatowicz, Jachowicz, Mrozianowski, Grigorowicz, Barowicz, Teodorowicz, among others.

The growth of Poland's Armenian community

.jpg.webp)

Through successive immigrations, the Armenians of Poland gradually formed a colony, comprising 5,000.[5] They were welcomed by the Kings of Poland and were granted not only religious liberty, but also political privileges. Casimir III (1333–1370) gave to the Armenians of Kamieniec Podolski in 1344 and those of Lwów in 1356 the right of setting up a national council, exclusively Armenian, known as the "Voit." This council, composed of twelve judges, administered Armenian affairs in full independence. All acts and official deliberations were conducted in the Armenian language and in accordance with the laws of that nation. The Armenians of Lwów had built a wooden church in 1183; in 1363 it was replaced by a stone edifice which became the seat of the Armenian prelates of Poland and Moldavia.

In 1516 King Sigismund I authorized the installation in the wealthy and aristocratic center of Lwów an Armenian tribunal called the Ermeni tora in Armeno-Kipchak (Datastan in Armenian). The peaceful life of the colony was troubled in 1626. An abbot named Mikołaj Torosowicz was ordained a bishop in 1626 by Melchisedek, a former coadjutor-Katholikos of Etchmiadzin who supported restoring unity with the Roman Catholic Church. Despite the ensuing rift between the majority of the Armenian community and the few followers of Torosowicz the Armenian community finally reentered into communion with the Holy See forming the Armenian Catholic Church which retained a separate hierarchy and used the Armenian Rite.

Ties to the Armenian community in the Romanian lands

Armenians in Moldavia were under the jurisdiction of the Armenian Diocese of L'viv since 1365, shortly after the principality was founded. As merchants, the Armenians mere present in many of the important commercial centers in the various polities which now make up Romania and Moldova. The oldest architectural monument built by Armenians on these lands and preserved to this day is the church of St. Mary of Botosani, built in 1350. Nicolae Șuțu writes in Notion statistiques sur la Moldavie (published in Iași, 1849): "From the 11th century, the Armenians, leaving their settlements invaded by the Persians, took refuge in Poland and Moldova. Subsequent emigrations took place in 1342 and 1606. The Armenian churches in Moldavia, the oldest of which is in Botoșani and founded in 1350, while the other is in Iași which dates from 1395." The fact that two Armenian Bibles from Caffa dating to 1351 and 1354 were preserved in this church is a testament to the antiquity and importance of the Armenian colony in Botoșani. During the short-lived persecution of the Armenian community under the reign of Moldavian Hospodar Ștefan VI Rareș, many Armenians fled across the border into Poland.

Around 10,000 of the L'viv Armenian community who had settled in Moldavia moved from there during the Turko-Polish war in 1671 to Bucovina and Transylvania. In Bucovina, they lived in the city of Suceava and its vicinity. In Transylvania they founded two new cities, Erszebetvaros (Elisabethstadt, Dumbrăveni) and Szamos-ujvar (Armenierstadt, Gherla), which, as a special favor, were declared free cities by Charles VI, Emperor of Austria (1711–1740).

When James Louis Sobieski attempted to ascend to the Moldavian throne, his base of operations was the 15th century Armenian monastery of Suceava. Beginning in 1690, the Monastery became the headquarters of the Polish Army for all of their operations in Moldova related to Poland's participation in the War of the Holy League against the Ottoman Empire. Staying at the monastery for several years, the Poles built an extensive network of bastion fortifications which are well preserved to this day. The popular name of the monastery, "Zamca" likely comes from this period and is derived from zamek, the Polish word for castle.

Intermarriage and assimilation

The Armenian origins of many Polish families can be traced to before World War II, the result of intermarriage. The Armenian cathedral of Lwów, modelled on the Cathedral of Ani, was an important site for religious pilgrimages. The last Armenian Archbishop in Poland, Józef Teodorowicz, as the head of the community, was a member of the Austro-Hungarian Senate, together with Roman Catholic and Greek Catholic colleagues.

Malyi Virmeny which translates to "Little Armenia" in Ukrainian is a historic old town once near the Smotrych River which was founded during the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Polish-Armenians in the 20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were about 6,000 Armenians in Poland living mostly in Eastern Galicia (today Western Ukraine), with centers in Lwów (Lviv), Stanisławów (Ivano-Frankivsk), Brzeżany (Berezhany), Kuty, Łysiec (Lysets), Horodenka, Tłumacz (Tlumach) and Śniatyn (Sniatyn). Polish-Armenians were an integral part of the movement to restore Poland's independence during World War I.

After suffering heavy losses along with the rest of Poland's population in World War II, the Polish Armenian community suffered a second loss. The regions of Poland where Armenians were concentrated such as Eastern Galicia were annexed into the Soviet Union as part of the agreements reached at the Yalta conference. As a result, the Polish Armenian community became dispersed all over Poland. Many of them were resettled in cities in northern and western Poland such as Kraków, Gliwice, Opole, Wrocław, Poznań, Gdańsk, and Warsaw.

To combat this dispersion they began to form Armenian Cultural Associations. Additionally, the Catholic Church opened two Armenian Catholic parishes with one in Gdańsk and the other in Gliwice, while Roman Catholic churches in other cities such as St. Giles in Kraków would from time to time also hold Armenian Rite services for the local Armenian community.

A number of cultural and artifacts of Armenian culture can still be found within Poland's present-day borders, particularly in the vicinity of Zamość and Rzeszów. Additionally, a number of Khachkars have been erected in front of several churches in Wrocław, Kraków, and Elbląg as memorials to commemorate victims of the Armenian genocide. It is unknown whether the Polish-Armenians were specific targets of Nazi Germany during World War II, though the Armenians were not scapegoated by the Nazis unlike Jews, Romani people and other minorities during the Nazi occupation of Poland.

Armenians today

Most Armenians living in Poland today origins are from the post-Soviet emigration rather than the older Armenian community. After the Soviet Union's collapse, thousands of Armenians came to Poland to look for the opportunity to better their life. It is estimated that between 40,000 and 80,000 Armenians came to Poland in the 1990s, (many of them returned to Armenia or went further West, but up to 10,000 stayed in Poland), with only about 3,000–8,000 from the so-called 'old emigration'.

The Foundation of Culture and Heritage of Polish Armenians was established by the Ordinary of the Armenian-Catholic rite in Poland, Cardinal Józef Glemp, the Primate of Poland, on April 7, 2006 to care for the books, paintings, religious remnants which were saved from perishing when carried away from Armenian churches situated in the Eastern former parts of Poland captured by the Soviets during World War II.[6]

The Armenian Rite Catholic Church which had been historically centered in Galicia as well as in the pre-1939 Polish borderlands in the east, now has three parishes; one in Gdańsk, one in Warsaw and the other in Gliwice.

There are also now schools in Poland that have recently opened or added on courses that teach Armenian language and culture either on a regular or supplementary basis in Warsaw and Kraków.

Notable Poles of Armenian descent

- Simeon of Poland (1584–1639), traveler and writer

- Kajetan Abgarowicz (1856–1909) — writer

- Fr. Karol Antoniewicz (1807–1852) — Catholic priest, Jesuit and poet

- Teodor Axentowicz (1853–1938) — painter

- Anna Dymna (b. 1951), actress

- Zbigniew Herbert (1924–1998) — poet and essayist

- Fr. Tadeusz Isakowicz-Zaleski (1956–2024) — Catholic priest, shepherd of the Armenian Rite faithful in southern Poland, historian, charity worker and independence activist during communist rule

- Jerzy Kawalerowicz (1922–2007) — film director

- Robert Maklowicz (b. 1963) — journalist

- Krzysztof Penderecki (1933–2020) — composer

- Fr. Grzegorz Piramowicz (1753–1801) — Catholic priest, educator and philosopher

- Juliusz Słowacki (1809–1849) — poet

- Szymon Szymonowic (1558–1629) — poet

- Abp. Józef Teodorowicz (1864–1938) — Armenian Catholic Archbishop of Lviv, renowned for his religious and social work.

- Sonia Bohosiewicz (b. 1975) — actress

See also

References

- 1 2 GUS. "Tablice z ostatecznymi danymi w zakresie przynależności narodowo-etnicznej, języka używanego w domu oraz przynależności do wyznania religijnego". stat.gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-10-07.

- ↑ "Poland's Armenian community is outstanding manifestation of Diaspora, says Ambassador". armenpress.am. Retrieved 2023-10-07.

- ↑ The First Large Emigration of the Armenians – History of Armenia

- ↑ Jakubowski, Melchior; Walczyn, Filip; Sas, Maksymilian (2016). "Jazłowiec". Miasta wielu religii. Topografia sakralna ziem wschodnich dawnej Rzeczypospolitej (PDF) (in Polish). Warsaw: Muzeum Historii Polski. p. 68-73. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ↑ Krzysztof Stopka, Ormianie w Polsce dawnej i dzisiejszej, Kraków 2000

- ↑ Website of the Foundation of Culture and Heritage of Polish Armenians

_2010-07-15_160.jpg.webp)