Augusto Boal | |

|---|---|

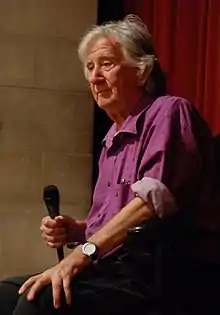

Boal presenting a workshop on the Riverside Church in New York, 13 May 2008. | |

| Born | 16 March 1931 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Died | 2 May 2009 (aged 78) Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Occupation | Theatre practitioner |

| Genre | Theatre of the Oppressed |

Augusto Boal (16 March 1931 – 2 May 2009) was a Brazilian theatre practitioner, drama theorist, and political activist. He was the founder of Theatre of the Oppressed, a theatrical form originally used in radical left popular education movements. Boal served one term as a Vereador (the Brazilian equivalent of a city councillor) in Rio de Janeiro from 1993 to 1997, where he developed legislative theatre.[1]

Biography

Early life

Augusto Boal studied at Columbia University in New York with the critic John Gassner. Gassner introduced Boal to the techniques of both Bertolt Brecht and Konstantin Stanislavski, and encouraged Boal to form links with theatre groups like the Black Experimental Theatre. In 1955 Boal staged productions of two of his own plays, The Horse and the Saint and The House Across the Street.[2] In 1956, shortly after graduating, Boal was asked to work with the Arena Theatre in São Paulo, southeast Brazil.[3] Boal was in charge of directing plays along with other dramaturgs such as José Renato, who was also the founder of the Arena Theatre. It was here that he began to experiment with new forms of theatre never before seen in Brazil, such as Stanislavski's 'system' for actors, with which he became familiar during his time at Columbia and when involved with the Actors Studio in New York. Boal adapted these methods to social conditions in Brazil, taking a leftist approach on issues concerning nationalism, which were very much in vogue at that time period since the country had just undergone a long period of military dictatorship.[4][5]

Work at the Arena Theatre of São Paulo

While working at the Arena Theatre in São Paulo, Boal directed a number of classical dramas, which he transformed to make them more pertinent to Brazilian society and its economy. Among these plays was John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men, known in Brazil as Ratos e Homens. This was Boal's first performance as a director at the Arena Theatre of São Paulo. Critics acclaimed this piece and Boal won the Prêmio de Revelação de Direção (Direction Revelation Award) from the Association of Art Critics of São Paulo, in 1956. In the early sixties, the ratings at the Arena Theatre of São Paulo started to drop, almost causing the theatre to go bankrupt. Consequently, the company decided to start investing in national theatre (pieces written by Brazilian dramaturgs) as a move that could possibly save it from bankruptcy. The new investment proved to be a success, opening up the path for a national theatre scene. Boal then suggested the creation of a Seminar in Dramaturgy at the Arena Theatre, which was quickly implemented and soon became a national platform for many young playwrights. Many successful productions were born from this Seminar and now form part of the Arena Theatre of São Paulo's nationalist phase repertoire. One of these productions was Chapetuba Futebol Clube, written by Oduvaldo Vianna Filho in 1959 and directed by Augusto Boal.[6]

Exile

A new military regime started in Brazil in 1964 with a coup d'état supported by the Brazilian elite, the industrialists, the military, as well as by the United States,[7] Boal's teachings were controversial, and as a cultural activist he was seen as a threat by the Brazilian military regime. In 1971, Boal was kidnapped off the street, arrested, tortured, and eventually exiled to Argentina,[1] where he stayed for five years. During those five years, Boal published two books: Torquemada (1971) and his much acclaimed Theatre of the Oppressed (1973). Torquemada is about the Brazilian military regime's systematic use of torture in prison.[8] Boal takes the name of the leading figure of the Spanish Inquisition, Tomas de Torquemada, as an example of historical forms of systematic torture. In Theatre of the Oppressed Boal develops a theatrical method based on Pedagogy of the Oppressed, a book by the Brazilian educator and writer Paulo Freire (who was also a good friend of Boal).[9]

Boal's method (which has been implemented in various communities around the world) seeks to transform audiences into active participants in the theatrical experience. Boal argues that traditional theatre is oppressive since spectators usually do not get a chance to express themselves and that a collaboration between both parties, in contrast, allows spectators to perform actions that are socially liberating. The method, as Boal liked to explain, seeks to transform spectators into "spect-actors."[10] When the political climate in Brazil forced Boal into exile in 1971, he initially went to Peru and then Argentina, where he completed and published his seminal theoretical work The Theatre of the Oppressed and consolidated his conscientização (consciousness-raising) theatre work based on the idea of Brazilian educationalist Paulo Freire.[3] Freire's methods were a revolt against the elitist "top-down" approach to education and he advocated critical-awareness-based education models. Boal's work in Peru with the ALFIN project, a movement which sought to use a range of languages including "artistic languages" to eradicate illiteracy, developed his ideas and methodology away from the agit-prop of his Brazilian Arena Theatre days and sought to engage theatre as a pedagogical tool. Crucial to this time was Boal's attempts to break down the divisions between spectator and actor. It is around this time that invented the term "spect-actor", a term that he saw as establishing the frameworks within which he wished to work.[2] He saw that the passivity of the spectator could be broken down by the following steps by which the spectator becomes the spect-actor:

- Knowing the body (by body he means both the individual "body" and the collective "body" in a Marxist sense)

- Making the body expressive

- Using theatre as a language

- Using theatre as discourse

After living in Argentina, Boal travelled to other countries in South America such as Peru and Ecuador, where he worked with people in small and usually poor communities that dealt with conflicts such as civil wars and lack of government attention. Boal was of the opinion that only the oppressed are able to free the oppressed. In Peru, Boal practiced his Forum theatre method, in which spectator replaces actor to determine the solution to a given problem presented by the actor, which can also be a real problem someone in the community is facing. Boal also lived in Paris, France, for a number of years, where he created several Centers for the Theatre of the Oppressed, directed plays, and also taught classes at the Sorbonne University. Boal created the first International Festival for the Theatre of the Oppressed in 1981.[8]

While Boal was in exile, his very close friend and Brazilian musician Chico Buarque wrote him a letter that would later result in the Chorinho hit called "Meu Caro Amigo" or "My Dear Friend" (1976). In this song, Buarque tells his friend about the situation in Brazil at the time, addressing the military dictatorship in a very subtle but clever way (due to censorship issues, many artists could not express themselves freely).[11] The melody of the song is very happy and upbeat while the lyrics explain:

My dear friend, please forgive me, if I can’t pay you a visit, but since I found someone to carry a message, I’m sending you news on this tape. Here we play football, there’s lots of samba, lots of choro and rock’n'roll. Some days it rains, some days it’s sunny but I want to tell you that things here are pretty dark. Here, we’re wheeling and dealing for survival, and we’re only surviving because we’re stubborn. And everyone’s drinking because without cachaça, nobody survives this squeeze.[12]

Center for the Theatre of the Oppressed-CTO-Brazil

After the fall of the military dictatorship, Boal returned to Brazil after 14 years of exile in 1986. He established a major Center for the Theatre of the Oppressed in Rio de Janeiro (CTO), whose objective was to study, discuss and express issues concerning citizenship, culture and various forms of oppression using theatrical language. Boal's work in the CTO made way for the approval of a new law that protects crime victims and witnesses in Brazil.[13] Boal's group has worked next to numerous organizations that fight for human rights. In 1992, Boal ran for city councillor in Rio de Janeiro as a theatrical act, and he was elected. Boal's support staff was his theatre group, with whom he quickly developed various legislative proposals. His objective was to work out issues citizens might be facing in their communities through theatre and also to discuss the laws of the city of Rio with people on the streets. After having worked to transform spectator into author in Theatre of the Oppressed, Boal initiates the legislative theatre movement process, in which voter becomes legislator. Boal is known to say that he did not create laws arbitrarily while he was city councillor. Instead, he asked people what they wanted. Other politicians were not very fond of this. Out of 40 of Boal's proposed laws, only 13 got approved during his term as councillor of Rio de Janeiro. His term ended in 1996, but he continued performing legislative theatre acts with different groups in Brasília, where four more laws got approved even after Boal had left. Boal also worked with prisoners in Rio and São Paulo. Boal argued that people in prison are not free in space, but that they are in time, and that the Theatre of the Oppressed strives to create different types of freedom so that people are able to imagine and think about the past, the present, and invent the future instead of having to wait for it. All this was in order for prisoners to have "a healthier and more creative lifestyle." People in the Movimento sem Terra or Landless Workers Movement of Brazil also experienced working with Boal's theatre methods. Boal's son Julián worked along with his father and now continues to take the Theatre of the Oppressed to various communities in Brazil and around the world. In March 2009, he received the title of "World Theatre Ambassador" from UNESCO.[14]

Death

Augusto Boal died on 2 May 2009 at the age of 78 in Rio de Janeiro. Critic Yan Michalski argues that Augusto Boal is the best-known and most respected Brazilian theatre practitioner abroad.[4]

Influences

Most of Augusto Boal's techniques were created after he realized the limitations of didactic, politically motivated theatre in the poor areas where he worked. He found that his attempts to inspire the people living in poor or "slum" areas to rise up against racial and class inequality were inhibited by his own racial and class background, since he was white and comparatively financially comfortable, as well as his and his colleagues' inhibitions to perform violence themselves. His new techniques allowed the idea of rebellion and the impetus for change to come from within the target group. Much of his early work and teaching was inspired by Marxist philosophy, although much of his work now falls within the boundaries of a center-left ideology.

Paulo Freire was a major influence on Boal's teachings. He and Freire became close in later years. When Freire died, Boal said: "I am very sad. I have lost my last father. Now all I have are brothers and sisters".[1]

Boal was also known to quote William Shakespeare's Hamlet, in which Hamlet argues that theatre is like a mirror that reflects our virtues and defects equally. Although Boal found this quote beautiful, he liked to think of theatre as a mirror in which one can reach in to change reality and to transform it.[15]

Published works

Theatre of the Oppressed (London: Pluto Press, 1979)

Arguably Augusto Boal's most academically influential work[16][17][18] is the Theatre of the Oppressed, in which the reader follows Boal's detailed analysis of the Poetics of Aristotle and the early history of Western theatre. Boal contends that the Aristotelian ethic means oppressing the masses, the people, the workers and the spectators in favour of stability and the continued dominance of a privileged few. He argues that the Tragi-drama, a formulaic drama style that today could be considered similar to that of soap operas, helps the State promote its continued existence. He sees the Brazilian government as an example of an oppressive state using theatre to propagate its oppressive system. He then outlines his early theories and practices for attempting to reverse the paradigm. It also talks about Newspaper Theatre, attempting to talk about local problems and present it to the audiences, Forum Theatre, currently used in over 70 countries, Invisible Theatre, used to discuss political activity and Image Theatre. Theatre of the Oppressed has been translated to more than 25 languages over the years. Boal also talks about Invisible theatre in which an event is planned and scripted but does not allow the spectators to know that the event is happening. Actors perform out of the ordinary roles which invite spectators to join in or sit back and watch. One example was in a restaurant at the Chiclayo hotel, actors sat at separate tables and informed the waiters in loud voices that they could not eat the food. The actor stated that the food was not good. The waiter says the diner could pick something else to eat. So the actor chose a rather expensive item off the menu and says he will be able to pay for it. The actor mentions he has no money and he would be willing to work for it. This display made other diners start discussing the price and treatment of workers at this hotel. This act allowed spectators to think about issues that were going on but was brushed over because the issue did not directly involve them.[19] Analytical theatre is when a participant tells a story and the actors improvise it. Each character is broken down into all the social roles they could follow and the participants choose an object to symbolize the role. This aspect of theatre allows the participants to see how there are multiple roles a person could follow.[19]

Games For Actors and Non-Actors (London: Routledge, 1992; Second Edition 2002)

This is probably Augusto Boal's most practically influential book, in which he sets down a brief explanation of his theories, mostly through stories and examples of his work in Europe, and then explains every drama exercise that he has found useful in his practice. In contrast to Theatre of the Oppressed, it contains little academic theory and many practical examples for drama practitioners to use even if not practising theatre that is related to Boal's academic or political ideas. Boal refers to many of these as "gamesercises", as they combine the training and "introversion" of exercises with the fun and "extroversion" of games. It has been influential in the development of Community Theatre and Theatre in Education (T.I.E.) practices worldwide, especially in Europe and South America. These games include Carnival in Rio and Your Friend is Dead.

The Rainbow of Desire: The Boal Method of Theatre and Therapy. (London: Routledge, 1995)

This book re-evaluates the practices commonly associated with the Theatre of the Oppressed for a new purpose. It has been argued that Boal contradicts himself with this take on his work,[20] as it mostly concerns itself with creating harmony within society, whereas his early work was concerned with rebellion and upheaval. Boal states that, "Theatre is the passionate combat of two human beings on a platform."[20] However, Boal's works can be seen as a progression and exploration of a Left Wing world view rather than a unified theory. In the context of those under-represented in a society, his methodology can be used as a weapon against oppressors. In the context of those in a society who are in need of catharsis for the sake of their own integration into it, it can be switched round to empower that individual to break down internal oppressions that separate that individual from society. Through his work at French institutions for the mentally ill and elsewhere in Europe, where he discovered concepts such as the "Cop in the Head", the theories presented in this book have been useful in the pioneering field of drama therapy and have been applied by drama practitioners. Boal states in his work that there are three properties of the aesthetic space. First, is plasticity. He says that one can be without being. Objects can acquire different meaning such as an old chair representing a king's throne. He states that only duration counts and location can be changed. Second, is that the aesthetic space is dichotomic and it creates dichotomy. This idea suggests that there is a space within a space. The stage is in front of the audience and the actor is creating his own space. Third, is telemicroscopic. This idea creates the idea that it is impossible to hide on stage. Every aspect of the space is seen and it makes the far away close-up.[20]

Other books

- Legislative Theatre: Using Performance to Make Politics. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Hamlet and the Baker's Son: My Life in Theatre and Politics. London: Routledge, 2001.tate

- The Aesthetics of the Oppressed. London: Routledge, 2006.

Recognition

In 1994, Boal won the UNESCO Pablo Picasso Medal,[21] and in August 1997, he was awarded the "Career Achievement Award" by the Association of Theatre in Higher Education at their national conference in Chicago, Illinois. Boal is also seen as the inspiration behind 21st-century forms of performance-activism, such as the "Optative Theatrical Laboratories".

Boal received The Cross Border Award for Peace and Democracy by Dundalk Institute of Technology in 2008.[22][23] Boal has in many ways influenced many artists in new media with his participatory modes of expression, especially as the World Wide Web has become such a powerful tool for participation and communication. Notable examples include Learning to Love You More, happenings, and Steve Lambert's Why They Hate US.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Paterson, Doug. A Brief Biography of Augusto Boal. ptoweb.or

- 1 2 Eckersley, M. (1995). "A Matter of Style – The Theatre of Augusto Boal". Mask Magazine. Vol. 18 No. 3. Drama Victoria. Melbourne.

- 1 2 Babbage, Frances (2004). Augusto Boal. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-27325-1.

- 1 2 Enciclopedia Itau Cultural- Teatro- Augusto Boal's Biography (In Portuguese)

- ↑ O Palco. Biographical info Augusto Boal (In Portuguese). Archived November 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Directly translated from the Augusto Boal Wiki page in Portuguese.

- ↑ Skidmore, Thomas (1999). Brazil: Five Centuries of Change. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-19-505810-0.

- 1 2 "murio augusto boal, creador del teatro del oprimido". Cafemoiru.blogspot.com (May 2009). Retrieved on 2019-09-06.

- ↑ "Theater of the oppressed". Spunk.org. Retrieved on 2019-09-06.

- ↑ es:Teatro del Oprimido

- ↑ Augusto Boal: candidato a Premio Nobel de la Paz, mandioca.lelê. Mandioca.wordpress.com (2008-02-14). Retrieved on 2019-09-06.

- ↑ My dear friends. lidous.net (2008-09-24)

- ↑ da Silveira, José Braz (2005). A proteção à testemunha & o crime organizado no Brasil. Jurua Editora. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-85-362-0763-6.

- ↑ Entrevista al brasileño Augusto Boal Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 38- Entrevista com Augusto Boal | Arquivo68. Josekuller.wordpress.com. Retrieved on 2019-09-06.

- ↑ The Theatre of the Oppressed: The Philosophy of Augusto Boal, by Kevin A. Harris Archived March 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The theatre of the oppressed, by Augusto Boal. UNESCO Courier, Nov, 1997.. Archive.today (2012-07-09). Retrieved on 2019-09-06.

- ↑ "Empowering the oppressed through participatory theatre, by Arvind Singhal" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- 1 2 Wardrip-Fruin, Noah, and Nick Montfort (2003). "From Theatre of the Oppressed." The New Media Reader. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT, 2003. pp. 339–52.

- 1 2 3 Boal, Augusto (1995). The Rainbow of Desire: the Boal Method of Theatre and Therapy. London: Routledge.

- ↑ UNESCO. World Theatre Day. Events.unesco.org. Retrieved on 2019-09-06.

- ↑ Denis Cummins to make presentation to Augusto Boal. Ww2.dkit.ie. Retrieved on 2019-09-06.

- ↑ "Augusto Boal unplugged at the Abbey". Archived from the original on 2008-12-13. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

External links

Media related to Augusto Boal at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Augusto Boal at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Augusto Boal at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Augusto Boal at Wikiquote- International Theatre Institute – Author of the World Theatre Day Message 2009 Augusto Boal

- International Theatre of the Oppressed Organisation.

- Theatre of the Oppressed Laboratory – New York City worked with Boal from 1991

- Augusto Boal Interview on Democracy Now! in 2005

- Augusto Boal, Founder of the Theatre of the Oppressed, Dies at 78 Interview on Democracy Now! in 2007

- Guardian Obituary, May 6, 2009

- New York Times Obituary, May 9, 2009

- A Tribute to a Brazilian Writer Who Made Theater into a Weapon for the Oppressed June 28, 2009

- Giolli, an Italian cooperative that works with his method August 11, 2009

- Cardboard Citizens – The UK's Theatre of the Oppressed Practitioners

- Centre for Community Dialogue and Change, India: Breaking Patterns, Creating Change – Conducting Theatre of the Oppressed Workshops and Research especially in Education and Healthcare

- Center for Theatre of the Oppressed