| Battle of Cedar Creek (Battle of Belle Grove) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Battle of Cedar Creek, by Kurz & Allison (1890) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 31,610 | 21,102 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

5,665

|

2,910

| ||||||

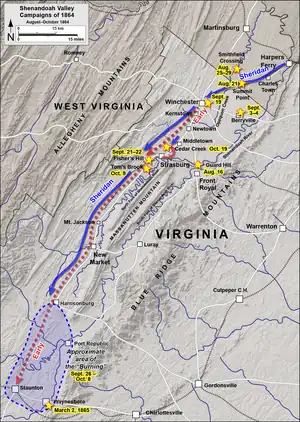

The Battle of Cedar Creek, or Battle of Belle Grove, was fought on October 19, 1864, during the American Civil War. The fighting took place in the Shenandoah Valley of Northern Virginia, near Cedar Creek, Middletown, and the Valley Pike. During the morning, Lieutenant General Jubal Early appeared to have a victory for his Confederate army, as he captured over 1,000 prisoners and over 20 artillery pieces while forcing 7 enemy infantry divisions to fall back. The Union army, led by Major General Philip Sheridan, rallied in late afternoon and drove away Early's men. In addition to recapturing all of their own artillery seized in the morning, Sheridan's forces captured most of Early's artillery and wagons.

In heavy fog, Early attacked before dawn and completely surprised many of the sleeping Union soldiers. His smaller army attacked segments of the Union army from multiple sides, giving him temporary numerical advantages in addition to the element of surprise. At about 10:00 am, Early paused his attack to reorganize his forces. Sheridan, who was returning from a meeting in Washington, D.C. when the battle started, hurried to the battlefield and arrived around 10:30 am. His arrival calmed and revitalized his retreating army. At 4:00 pm his army counterattacked, making use of its superior cavalry force. Early's army was routed and fled south.

The battle ruined the Confederate army in the Shenandoah Valley, and it was never again able to maneuver down the valley to threaten the Union capital city of Washington, D.C. or northern states. Additionally, the Shenandoah Valley had been a key producer of supplies for the Confederate army, and Early could no longer protect it. The Union victory aided the reelection of Abraham Lincoln, and along with earlier victories at Winchester and Fisher's Hill, won Sheridan lasting fame.

Background

Union and Confederate strategies for Virginia in 1864

In March 1864, Major General Ulysses S. Grant was summoned from the Western Theater, promoted to lieutenant general, and given command of all Union armies.[1] Grant's strategy, different from his predecessors, was for the Union armies to fight together with the objective of destroying Confederate armies instead of conquering territory. He would use multiple Union forces at the same time, making it difficult for the Confederates to transfer forces from one battlefront to another.[2] In Virginia, General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was a target. Not only would Lee's army be pursued, but steps would be taken to cut off its supplies that came from Virginia's Shenandoah Valley.[3] Those supplies often moved on the Virginia Central Railroad, Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, and other railroads—which also became targets.[4]

The Confederate Army of the Valley was created by Lee in June 1864 as a detachment of the Army of Northern Virginia's Second Corps and was commanded by Lieutenant General Jubal Early.[5] Its purpose was to protect the Shenandoah Valley, which was a major source of food for Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Another objective was to threaten the Union's capital of Washington, forcing the Union to divert resources and relieve some of the pressure on the Army of Northern Virginia near the Confederate capital of Richmond.[6] In June, Early beat Union forces in the Battle of Lynchburg and Second Battle of Kernstown.[7][8] On July 9, he won the Battle of Monocacy in Maryland.[9] Two days later, Early threatened Washington in the Battle of Fort Stevens, but was repelled by reinforcements rushed to the battlefield.[10] Early then sent cavalry commanded by Brigadier General John McCausland on a northern raid in late July that resulted in the burning of the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.[11]

Sheridan's campaign

After the cavalry raid that burned Chambersburg, Grant decided that Early's threat had to be eliminated.[12] In early August, Grant consolidated four military organizations into the Middle Military Division, and Major General Philip Sheridan assumed command on August 7—calling his force of cavalry and infantry the Army of the Shenandoah.[13] At its creation, the army had three objectives. First was to drive Early's army away from the Potomac River region and lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley, and pursue it southward. Second was to destroy the valley's capacity to provide Lee's army with food and supplies. Third was to disrupt the Virginia Central Railroad.[14]

Sheridan was cautious in August because of a concern that any military disaster could hamper the re–election of President Abraham Lincoln.[15] In September Sheridan had decisive victories over Early at the Third Battle of Winchester and at Fisher's Hill.[16] Sheridan took possession of the Shenandoah Valley as far south as Staunton, Virginia, and considered Early's army cleared from the valley.[17]

With Early much less of a threat, Sheridan could focus on denying the Confederacy the means of supplying its armies in Virginia. Sheridan's army (mostly cavalry) did this aggressively, burning crops, barns, mills, and factories. The operation, conducted primarily from September 26 to October 8, has been known to locals ever since as "the Burning" or "Red October".[18] It encompassed the area of Harrisonburg, Port Republic, Staunton and Waynesboro.[19] Sheridan claimed that when the destruction was completed, "the Valley, from Winchester up to Staunton, ninety-two miles [148 km], will have but little in it for man or beast."[20][Note 1] While this action achieved one of Grant's goals, Grant preferred attacks on the railroads that supplied Lee's army in Richmond.[22][Note 2]

Early reinforced

After Early's September 22 defeat at Fisher's Hill, he retreated up the valley (south) to Mount Jackson.[23] On September 26, he was reinforced by the infantry division of Major General Joseph B. Kershaw, who also brought a battalion of artillery.[24] More reinforcements arrived on October 5, when the Laurel Brigade of Brigadier General Thomas L. Rosser also joined Early and was combined with two other cavalry brigades to form a division commanded by Rosser.[25] Early believed that the addition of Kershaw's Division (2,700 fighters), Rosser's Laurel Brigade (600 men), the artillery battalion, and the return of stragglers from the September battles almost made up for his losses at Winchester and Fisher's Hill.[25][26]

After much of "The Burning" was conducted, Sheridan's cavalry began moving north down the valley. The Confederate cavalries of Major General Lunsford L. Lomax and Rosser harassed Sheridan's rear guard. By October 8, Rosser's men were near the Union cavalry division commanded by Brigadier General George Custer, while Lomax was near the division commanded by Brigadier General Wesley Merritt. On that evening, an annoyed Sheridan told his cavalry commander, Brigadier General Alfred Torbert, to "whip the rebel cavalry or get whipped".[26] On October 9, in the Battle of Tom's Brook, Custer and Merritt routed the Confederate cavalry in a battle that was described by Torbert as "the most decisive the country had every witnessed".[27]

Opposing forces

Union

.jpg.webp)

In mid-October, the Army of the Shenandoah had 11 divisions plus artillery units, totaling about 31,610 effectives with 90 artillery pieces.[28][Note 3] A few days before the battle, Sheridan attended a meeting in Washington, and Major General Horatio Wright commanded the army in Sheridan's absence.[30] The Union forces were divided into the following:

- VI Corps had three infantry divisions and an artillery brigade, and was commanded by Major General Horatio Wright.[31] When Wright temporarily commanded the army during Sheridan's initial absence from the battle, the corps was commanded by Brigadier General James B. Ricketts.[32] At least one historian says Wright's fighters had a reputation for "steadfastness and reliability".[33] The VI Corps consisted of 8,506 infantry effectives. In addition, they had 600 men operating 24 artillery pieces.[34][Note 4]

- XIX Corps, consisting of two infantry divisions, was commanded by Brigadier General William H. Emory.[34][Note 5] It consisted of 8,748 infantry effectives.[Note 6] In addition, it had 414 men operating 20 artillery pieces.[34] The XIX Corps was considered far behind the VI Corps in discipline and efficiency.[37]

- The Cavalry Corps, consisting of three divisions and a section of horse artillery, was commanded by Major General Alfred Torbert.[38] It had 7,500 effectives plus 642 artillerists operating 30 artillery pieces.[34] The three division commanders were Merritt, Colonel William H. Powell, and Custer.[39] Fifteen regiments were completely armed, and three more were partially armed, with the carbine version of the seven-shot Spencer repeating rifle.[40]

- The Army of West Virginia functioned as an infantry corps in Sheridan's Army of the Shenandoah, and is sometimes incorrectly identified as the VIII Corps.[Note 7] It was commanded by Brigadier General George Crook, and had two divisions plus an artillery brigade.[44][Note 8] Crook's effectives for the battle consisted of only 4,000 infantry men plus 200 artillerists manning 16 artillery pieces.[34][Note 9] To bolster Crook's small force, a Provisional Division of 1,000 men was attached.[28][Note 10] The Provisional Division's "reliability in combat was suspect".[47]

Confederate

Early's Confederate Army of the Valley had an estimated 21,102 effectives.[Note 11] In addition to his troops originally from Army of Northern Virginia's Second Corps, this figure includes over 3,000 men from Kershaw's infantry division, 2,206 men from Rosser's cavalry division after the addition of the Laurel Brigade, and 1,101 artillerists.[48] The Confederate forces were divided into the following:

- Infantry consisted of five divisions. Early's division commanders were Major General Stephen Dodson Ramseur, Brigadier General John Pegram, Major General John Brown Gordon, and Brigadier General Gabriel C. Wharton.[48] Kershaw commanded a fifth division, which was attached from Lieutenant General James Longstreet's First Corps.[24] The remainder of Longstreet's First Corps, which was an elite Confederate fighting unit, was not present.[51][52] Gordon was Early's second–in–command.[53]

- Cavalry consisted of two divisions. Major General Lomax commanded his own division, and it consisted of four brigades.[54] His men were armed with rifles and had no pistols or sabers, making the division more like mounted infantry which could not fight on horseback.[55] Rosser commanded Fitzhugh Lee's Division, which was composed of three brigades including Rosser's Laurel Brigade.[56] Rosser had a reputation as one of the most aggressive and successful cavalry commanders in the Army of Northern Virginia, but had never commanded anything larger than a brigade of four regiments.[57] The Laurel Brigade was composed of confident veterans with many victories over Union cavalry.[26]

Disposition of forces and movement to battle

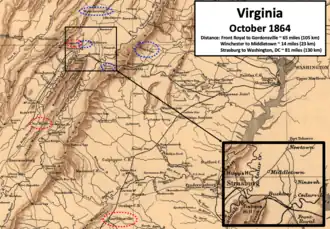

Sheridan ready to leave the valley

After the decisive victory at Tom's Brook, Sheridan and many in the Union Army believed that Early's Confederate army was no longer a threat. The Union army began moving down the valley (northeast) and believed that it would fight elsewhere.[58] While Crook's Army of West Virginia, and the XIX Corps, camped near Cedar Creek and Middletown, the VI Corps was further away on the road to Front Royal. The cavalry divisions of Merritt and Custer were near Fisher's Hill, while Powell's 2nd Cavalry Division occupied Front Royal.[59]

Because Grant still wanted the Confederate Virginia Central Railroad disabled, two brigades of cavalry from Powell's Division were sent south to attack the railroad lines at Gordonsville and Charlottesville.[59][Note 12] In an order written October 12, Wright's VI Corps were ordered to depart on the next day through Ashby's Gap for Alexandria, Virginia.[62] From Alexandria, Sheridan planned to send the VI Corps to reinforce Grant and the Army of the Potomac.[63]

Hupp's Hill and Sheridan goes to Washington

Concealed from Sheridan's army, Early's troops arrived at Hupp's Hill, just north of Strasburg, on October 13.[64] They deployed in battle formation, and began shelling the camp of the XIX Corps.[65] Early's attack was a surprise for the Union infantry, and Crook originally believed the Confederates had sent a small reconnaissance force for the purpose of causing the Union soldiers to reveal their strength and location.[66] Colonel Joseph Thoburn's division from the Army of West Virginia moved forward to silence the guns and fought with Kershaw's division at the Abram Stickley farm, which resulted in 209 Union and 182 Confederate casualties.[67][Note 13] The Confederates withdrew through Strasburg to Fisher's Hill in the late afternoon. Sheridan recalled Wright's VI Corps that evening as a precaution, and they started back to Middletown on October 14.[67] The engagement was a mistake for Early, as the 9,000 veterans from the VI Corps made a big difference in the battle that would take place six days later.[64]

On October 13, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton requested that Sheridan come to Washington to discuss the next objective for Sheridan's army.[68] Grant and Stanton still wanted Sheridan to move his army toward Gordonsville and Charlottesville to threaten Confederate railroad operations. Sheridan continued to argue that the logistics would be difficult.[22] With the skirmish at Hupp's Hill over and Early removed to Fisher's Hill, Sheridan departed for a meeting in Washington on October 15, leaving Wright in command.[63] Sheridan ordered all three divisions of cavalry to accompany him to Front Royal, intending to send them to destroy a Virginia Central Railroad bridge. They arrived near Front Royal on October 16.[69] At that time, Sheridan was notified that Early was sending wig-wag signals implying that Longstreet's First Corps might join him (Early) from Petersburg. This was disinformation on Early's part, hoping that it would induce the Federals to withdraw down the Valley, but instead, Sheridan sent his cavalry back to the infantry camps along Cedar Creek.[70] Sheridan and his staff arrived in Washington on the morning of October 17.[71]

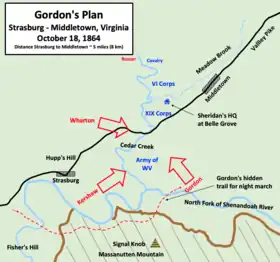

Gordon makes a plan

On October 17, Gordon climbed Massanutten Mountain and determined that the Union left was vulnerable, as the Union forces appeared to be relying on the mountain and rivers for defense.[63][72][Note 14] Gordon persuaded Early to approve an attack on the Union left flank, and believed they could destroy Sheridan's army.[74] Early's approval was contingent on Gordon finding a concealed route that would enable the Confederate troops to get around the Union left. On the next day, Gordon scouted along the Shenandoah River (North Fork), and found a narrow trail. He presented his findings to Early, and Early approved an attack that would begin on the morning of October 19.[75]

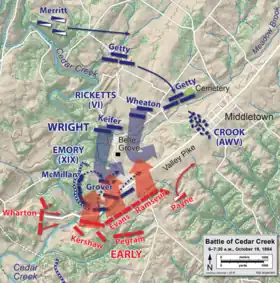

The attack would be made before dawn, and would take advantage of the morning fog that normally occurred in the valley. Gordon would lead three divisions in a rear attack on the Union left while Kershaw's Division would attack the front. Wharton's Division and the artillery would attack down the pike, northwest of Kershaw, waiting until the Union artillery was turned toward Gordon and Kershaw. Rosser would move north along Cedar Creek, hoping to keep Union cavalry located on the Union right from coming to assistance on the Union left.[76] Gordon's force would use the narrow mountain trail to get behind the Union left, which required an evening (October 18) departure time in order to be in position before dawn. A small brigade of cavalry commanded by Colonel William H. F. Payne would move with Gordon with the mission of capturing Sheridan at his headquarters at the Belle Grove Plantation house near Middletown.[77] Lomax would move via Front Royal to Newtown (later named Stephens City), where he could cut off a Union retreat down the Valley Pike.[78] During the time Gordon had command of the column of three divisions, Brigadier General Clement A. Evans would command Gordon's Division.[79] On October 18, the Confederate leaders synchronized their timepieces.[80] They planned to be in position for the attack at 5:00 am.[77]

Battle

Confederate attacks

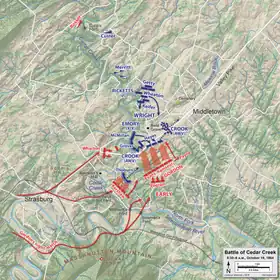

Early's infantry began to form into three columns on the evening of October 18. Gordon's column consisted of the divisions of Gordon (commanded by Evans), Pegram, and Ramseur, plus Payne's Cavalry Brigade. It had the farthest to march, and departed about 8:00 pm, just after it became dark.[77] The men left behind anything that might rattle, and followed the narrow trail in single file. The other two Confederate columns, commanded by Wharton and Kershaw, departed at about 1:00 am on October 19, and Early rode with Kershaw to Cedar Creek.[81] As they hoped, the Confederates' quiet approach was aided by the presence of heavy fog. All three columns were in position by 3:30 am.[81] The two Confederate cavalries were also in position. Rosser's dismounted cavalry (less Payne's Brigade), was near the ford at Cupp's Mill.[82] His men skirmished briefly with Custer around 4:00 am.[81] Lomax's cavalry was east near Cedarville and Front Royal. His command was as far as 27 miles (43 km) from Early's infantry, making cooperation difficult.[83] Early joined Wharton around 5:15 am.[84]

Army of West Virginia

"Men, shoeless and hatless, went flying like mad to the rear, some with and some without their guns."

Captain D. A. Dickert

3rd South Carolina Infantry Regiment (Kershaw's Division)[85]

Kershaw's Division attacked the trenches of Thoburn's Union 1st Division around 5:00 am.[81][Note 15] Surprise was virtually complete and most of the Army of West Virginia troops were caught unprepared in their camps—many were asleep in their tents.[80] The Union 1st Division lost most of its organization as most of its men fled—if they could.[85] Its First Brigade, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Wildes, kept two of its three regiments organized.[Note 16] The partial brigade conducted a fighting withdrawal to the Valley Pike that took over 30 minutes.[81] Union Captain Henry A. du Pont, chief of Colonel Crook's artillery, saved nine of his sixteen artillery pieces while he kept them in action as he withdrew toward Middletown.[88] Du Pont's efforts and Wildes' two regiments were only thing (other than fog) slowing the initial Confederate thrust by Kershaw's Division.[87][Note 17] The Union 1st Division commander, Colonel Thoburn, was mortally wounded by Confederate cavalry while trying to rally his troops near Middletown.[90]

Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, commander of the Union 2nd Division, learned of the attack on Thoburn's division only a few minutes before his own division was attacked by a line of seven brigades from Gordon's column.[86] Evan's (Gordon's) Division was on the Confederate left, and Ramseur's Division was on the right.[91] Hayes had two brigades, and only his First Brigade was in formation to receive Gordon's attackers. His Second Brigade, located on his right (southwest), was still in their tents—and then had Thoburn's retreating men racing through their camp. Soon, Hayes' division was also retreating.[86] Most of Hayes' men retreated toward Belle Grove, while most of Thoburn's men retreated northeast down the pike.[92] During the retreat, Hayes' horse was killed and he was briefly knocked unconscious. Although injured and almost captured, he escaped.[93] Further north, Union Colonel J. Howard Kitching's Provisional Division of raw recruits fled after showing little resistance. On horseback, Kitching was wounded in the foot, but continued trying to rally his men.[94][Note 18] Kitching's 6th New York Heavy Artillery Regiment, coming in from camp near the wagons, supported one of du Pont's batteries.[93] Although the Confederate attacking force from Ramseur's Division suffered minimal casualties, Brigade Commander Cullen A. Battle was seriously wounded. Crook, Hayes, and Kitching regrouped fragments of the two Union divisions near Belle Grove.[95]

XIX Corps

Unlike Crook's men, the Union XIX Corps was not caught totally unprepared. Its 2nd Division, commanded by Brigadier General Cuvier Grover, was planning to undertake a reconnaissance mission at 5:30 am south toward Strasburg.[96] Around 5:15 am they could hear musket fire near the Army of West Virginia's position, and Grover positioned his men defensively—with the bulk of his men behind fortifications.[96][Note 19] The XIX Corps began receiving artillery fire from the south and east, and was attacked from those directions by Confederate troops, commanded by Kershaw and Evans, less than one hour after the start of the battle.[97]

XIX Corps Commander Emory received unexpected assistance from Wildes' partial brigade from Crook's Army of West Virginia. In the confusion of battle, Wildes' two regiments had been unable to reunite with Crook and the retreating men from the Army of West Virginia—so they offered assistance to Emory and Wright. When the partial brigade reported, Emory ordered it to attack—which would enable his men to have more time for reorienting the Union lines. Wright led a bayonet charge by Wildes' men and received a bloody wound to his face.[98]

The small group of Crook's men at Belle Grove, fortified by some of Emory's men, held its position for about 40 minutes until it was flanked. Their action enabled most of the Union headquarters units and supply trains to withdraw to safety.[99] In roughly two hours, Early had driven back five Union divisions, captured over 1,300 prisoners, and taken possession of 18 artillery pieces.[100] With many of Crook's men from the Army of West Virginia and the XIX Corps fleeing in disorder, the Union's VI Corps prepared a defense on a series of ridges further north of the Belle Grove plantation on the north side of Meadow Brook.[101]

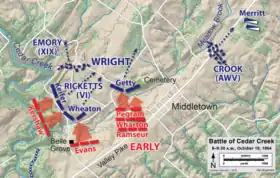

Early, Gordon, and the VI Corps

Sometime between 7:00 and 7:30 am, Early met Gordon on the east side of the Valley Pike near the road that leads to Belle Grove.[102] At that time, Kershaw and Evans were driving toward the camps of the Union VI Corps, and the Confederate divisions of Pegram and Ramseur were aligned along the west side of the pike north of Early and Gordon's meeting place.[103] Early later wrote that at the time of the meeting, "...the 19th and Crook's corps were in complete rout, and their camps, with a number of pieces of artillery and a considerable quantity of small arms, abandoned."[104] He also noted that the position of the Union VI Corps on a ridge west of Middletown was "a strong one", and Wharton's division had been driven back.[105] Early and Gordon had conflicting versions of their meeting, but Early took over command and Gordon returned to his division that had been temporarily commanded by Evans. From Gordon's point of view, he wanted to concentrate an attack on the VI Corps while Early was satisfied with the day's accomplishments.[102] From Early's point of view, he "rode forward on the Pike to ascertain the position of the enemy, in order to continue the attack."[104] Wharton's Division, plus artillery, followed Early down (northeast) the pike.[103]

Acting Union VI Corps Commander Ricketts had his men moving to position within 20 minutes of the start of the Confederate offensive.[32] His 3rd Division of Colonel J. Warren Keifer was on the Union right with the 1st Division of Brigadier General Frank Wheaton on its left. Further northeast, the 2nd Division of Brigadier General George W. Getty had marched close to the south side of Middletown.[106] All three Union divisions were eventually pulled back to a defensive position on the northwest side of Meadow Brook. Some cohesion was lost for this withdrawal, as Ricketts was wounded.[32] The Confederates attacked around 7:30 am, with Kershaw attacking Keifer, and Evans attacking Wheaton.[Note 20] Although initially repulsed, Kershaw and Evans drove the two Union divisions northwest by 8:00 am.[110] This put two Confederate divisions, Kershaw and Evans, beyond Getty's right. At that time, Getty's 2nd Division became the only organized Union infantry south of Middletown. With no support on his right, Getty moved his division back about 300 yards (270 m) to a stronger defensive position at the town cemetery on a partially wooded hill west of Middletown.[111] For over an hour, Getty's division defended this position against Confederate frontal assaults from the divisions of Ramseur, Pegram, and Wharton.[112][Note 21] During this time, Getty assumed command of the VI Corps because of the wounding of Ricketts, and Brigadier General Lewis A. Grant assumed command of the division.[113] After 30 minutes of artillery fire, Grant finally moved back and rested for 20 minutes. He then moved the division back about one mile (1.6 km), unopposed, where he found support from Union cavalry on his east side.[108]

Union cavalry and Sheridan's ride

Custer and Merritt's Union cavalry divisions were north of the infantry when the Confederate attack began. Although Rosser had skirmished with Custer's men, he appeared tentative and did not press an attack. While waiting for orders, both Merritt and Custer sent their escort companies to the Valley Pike to attempt to stop Union infantry men from fleeing toward Winchester.[114] Between 9:00 am and 10:00 am, Wright ordered Torbert to move the cavalry from the Union right to the Union left. Leaving three companies from Custer's Division to face Rosser, Custer and Merritt moved to the west side of the Valley Turnpike, about three quarters of a mile (1.21 km) northeast of Middletown. Although they faced strong artillery fire, they prevented Early from getting to the rear of the Union army.[114]

On his return trip from the Washington conference, Sheridan spent the night in Winchester on October 18.[115] At 6:00 am on October 19, pickets south of Winchester reported to him that they heard the distant sounds of artillery. Sheridan assumed the noise was from Grover's reconnaissance mission, and dismissed the report.[116] As additional reports arrived, he ordered the horses to be saddled and ate a quick breakfast.[117] By 9:00 am he was riding south to the Valley Pike.[118] Sheridan noticed that the sounds of battle were increasing in volume quickly, so he inferred that his army was retreating in his direction.[119] He encountered retreating men and wagons less than two miles (3.2 km) south of Winchester.[120] Hearing stories from panic stricken men that all was lost, he ordered a line set up to intercept stragglers.[121] Wright had already begun to organize a defensive line between Newtown and Middletown. Sheridan arrived around 10:30 am and began to rally the men to complete the line.[122] His presence inspired his soldiers, and one soldier described it as like an "electric shock".[123]

Early's halt

By 10:00 am, Early believed he had a Confederate victory, after capturing 1,300 Union prisoners and 24 artillery pieces, and driving seven infantry divisions off the field.[124] When Early rode into Middletown, he found that the Confederate attack had been stalled by Union artillery and cavalry. Ironically, the main reason two of the Union cavalry divisions were present for the battle was Early's Longstreet ruse from a few days earlier.[125] Instead of exploiting his victory, Early ordered a halt in his offensive to reorganize, a decision for which he later received criticism from subordinates such as Gordon.[126]

In a second meeting with Early, Gordon wanted to press the attack against the VI Corps immediately, and later wrote that the "fatal halting...converted the brilliant victory of the morning into disastrous defeat in the evening".[127][Note 22] Early's main reason for caution was concern over the Union cavalry, which had repeating rifles, on the Confederate flanks.[Note 23] Another problem was that many of the hungry Confederate troops had stopped to plunder the Union camps abandoned in the early morning attack.[128] By 11:30 am, the Confederate line was ready to continue the advance, and Early attacked with Gordon's, Kershaw's, and Ramseur's divisions. After an advance of about one–half mile (0.80 km), the Confederate attack stopped at 1:00 pm.[128] Early's reasons for the ending the attack were the same issues causing his caution a few hours earlier: Union cavalry, missing troops that were plundering the Union camps, and exhausted and hungry soldiers.[128]

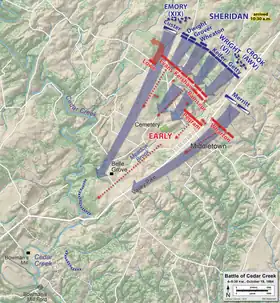

Union counterattack

When Sheridan arrived at the scene of the battle at 10:30 am, he assumed that Early's Longstreet ruse from a few days earlier was true. After interrogating prisoners, he learned that only Kershaw's Division from Longstreet's corps was present. Sheridan also feared that Longstreet was approaching from Front Royal to trap the Union army between Longstreet and Early. Once Sheridan received confirmation (around 3:30 pm) that Longstreet was not near Front Royal, he ordered an attack.[130]

The Union counterattack began just before 4:00 pm.[51] Custer's Division was back on the Union far right, further northwest from the main infantry line, facing Rosser. Merritt's Division was on the Union left on the southeast side of the pike.[131] The XIX Corps, with Brigadier General William Dwight now commanding the 1st Division and Grover returning to command the 2nd Division, was on the right of the main Union line.[Note 24] The VI Corps was to the left of Grover. Crook's Army of West Virginia was held in reserve close to the turnpike, as support for the VI Corps.[51] Sheridan's plan was for his cavalry to contain the Confederate flanks while the XIX Corps turned the Confederate left flank and drove them east of the pike, which would prevent Early's army from using the Valley Pike's bridge across Cedar Creek to escape.[133]

The Union infantry attack stalled. Dwight was able to overlap Gordon's left flank, but could not push Gordon's Division toward the pike. On Gordon's right, the divisions of Kershaw and Ramseur were positioned behind stone walls and assisted by artillery. Grover's Division and Wright's VI Corps had little success against them, and Grover was again wounded.[134] On the Union left, Merritt's cavalry made two charges only to be repulsed by Confederate artillery and enfilading fire from enemy infantry that had resisted the advance of the VI Corps.[131] On Merritt's third charge, bolstered by the VI Corps moving forward, Confederate troops gave way in disorder.[131] Moments before the Confederate troops fled, Union Colonel Charles Russell Lowell, commander of Merritt's Reserve Brigade located at the Union cavalry's left flank, was mortally wounded at Thorndale Farm.[135]

Custer joins the attack

On the extreme Union right, Custer's First Brigade was engaged in halfhearted fire with Rosser. Custer left his brigade commander with three of his regiments, and took the remaining men from his division toward the infantry attack on his left. He planned to get to the rear of Early's men and secure the Valley Pike at the bridge over Cedar Creek—which would cut off the main Confederate route of retreat.[136] As many of the Confederate soldiers saw Union cavalry moving toward their escape route, they began to panic and retreat.[137] The appearance of Custer riding toward the creek was a signal for Dwight to resume his infantry attack. The remnants of Gordon's Division, already panicked from Custer's appearance, now had a renewed attack from Dwight and more Union infantry on the Confederate right. Soon most of Gordon's men fled toward the pike, and it caused a domino effect that spread to Kershaw's Division and then Ramseur's.[138] During this time, Ramseur, who was already wounded, tried to rally his men. His horse was shot dead, and he was mortally wounded.[139]

While Custer was on the Union right, Merritt's Division was on the Union left. Colonel Thomas Devin's Second Brigade from Merritt's Division took possession of the Cedar Creek bridge before Custer got there, so Custer took his two lead regiments (5th New York and 1st Vermont) to the right of the bridge where they forded the creek and continued chasing the fleeing enemy up (south) the Valley Pike.[137] Near 5:30 pm, the divisions of Wharton, Pegram, and Wofford's Brigade (from Kershaw's Division) were the last Confederate units to across Cedar Creek.[Note 25] The fields between Cedar Creek and Fisher's Hill were filled with fleeing men, wagons, ambulances, and artillery—all being chased by Union cavalry using sabers.[142] The situation worsened for the Confederates when a small bridge on the Valley Pike south of Strasburg collapsed, making it impossible to cross with wagons or artillery. Early's army was forced to abandon all of the captured Union guns and wagons from the morning attack, as well as most of its own. Sheridan's pursuit ended at nightfall. The retreating Confederate soldiers gathered temporarily on Fisher's Hill, and moved further south before dawn on the next day.[143]

Casualties

The official report for the Union listed 644 officers and men killed, 3,430 wounded, and 1,591 captured or missing—a total of 5,665 casualties for the Union side of the battle.[144] Both the VI Corps and XIX Corps had over 2,000 casualties, but the VI Corps had more killed and wounded. As the principal victims of the surprise attack, the Army of West Virginia had 540 men captured or missing, and 790 of the XIX Corps' 2,383 casualties were captured or missing.[144] Crook's Army of West Virginia had two division commanders killed or mortally wounded, colonels Thoburn and Kitching.[145][146] Two Union brigade commanders were killed: Brigadier General Daniel D. Bidwell from the VI Corps, and Colonel Charles Russell Lowell from the Cavalry Corps.[145]

Confederate casualties, which are less certain, are estimated to be 320 killed, 1,540 wounded, and 1,050 missing (or captured).[147] This totals to 2,910, which is far less than the Union casualties. The Confederates also lost 300 wagons and ambulances, and 43 artillery pieces (including 20 Union pieces captured in the morning).[147][Note 26] The highest ranking Confederate casualty was Major General Ramseur, an infantry division commander, who was mortally wounded and captured by the 1st Vermont Cavalry Regiment.[150] The Union army captured many more soldiers than the 1,591 count, including some soldiers multiple times, but many prisoners escaped in the darkness while their captors searched for more men.[148] Among those that escaped was Early's artillery chief, Colonel Thomas H. Carter.[142]

Aftermath

Performance and impact

Three factors contributed to the initial success by the Confederate army. First, many of the soldiers in the Union army believed the campaign against Early's army was over, which caused a lack of vigilance. Second, the terrain and poor placement of the Union infantry units created a vulnerability that allowed the Confederates to surprise, flank, and outnumber segments of the Union army. Third, Union cavalry was misplaced, leaving open the left flank.[151] Once the Union cavalry was utilized, it had a crucial role in the Union victory.[126] Cavalry accounted for nearly half (ten of twenty-one) of the medal of honor winners at Cedar Creek, even though it had only about one fourth of the men present.[152] Two days after the battle, Sheridan sought promotions for two cavalry commanders, Merritt and Custer, and one infantry commander, Getty.[153]

Many people gave Sheridan credit for the Union victory, and he was featured on the cover of Harper's Weekly.[154] [155] It is "beyond dispute" that Sheridan had an electrifying effect on his men when he arrived at the battlefield.[154][156] Others believe that Wright deserves much of the credit, as his VI Corps stopped the Confederate attack, and Wright's tactical judgements made it possible for Sheridan to successfully rally his men.[154] Some credit for the Union victory can be given to Confederate leader Jubal Early. Although the early morning Confederate infantry and artillery attack was well-planned and attained total surprise, Early's cavalry was divided and awkwardly placed.[157] The Confederate army's relative inactivity after 10:00 am, one of Gordon's complaints, allowed the Union army to reorganize and eventually win the battle.[154] Gordon, the architect of the early morning attack and a critic of Early, received blame from Early for the stalling of the attack. Early claimed that excessive plundering by Gordon's Division depleted his force, and the depletion plus the threat of Union cavalry on his right flank caused the pause in the attack.[158]

Sheridan's victories in the Shenandoah Valley helped boost President Lincoln's re-election campaign to victory in November.[159] Earlier in August, Lincoln was being advised that his reelection was in doubt.[160] The Union army's numerical superiority was in trouble, and the country was tired of the war.[161][Note 27] Lincoln was overjoyed with the victory at Cedar Creek, as it came three weeks before the presidential election.[163] Sheridan enjoyed instant acclaim, and poet Thomas Buchanan Read wrote a popular poem, Sheridan's Ride, that added to the general's fame.[164] Sheridan's success propelled him to status only eclipsed by Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman, and he would eventually become Commanding General of the United States Army.[165] An equestrian statue of Sheridan rallying his men at Cedar Creek, sculpted by Gutzon Borglum, was dedicated in 1908 and stands in Washington, D.C.'s Sheridan Circle. [166] Contrasting Sheridan's fame, Early's status declined considerably. He was accused of incompetence and mismanagement, and no longer had the confidence of his subordinates.[167] Portions of his army were recalled to Richmond.[168] On March 2, 1865, Early and the remnants of his army were defeated by Custer in the Battle of Waynesboro, and the Army of the Valley ceased to exist. Although Early escaped, his artillery, wagons, and headquarters equipment were captured—and his men were captured, killed, or scattered to the countryside.[169][170]

Battlefield preservation

Portions of the Cedar Creek battlefield are preserved as part of Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park, established in 2002.[171] The park encompasses about 3,700 acres (1,500 ha) across three counties, and has trails, exhibits, and the Belle Grove Plantation Manor House.[172] Belle Grove, built in the 1790s by the brother-in-law of future President James Madison, was listed in the Virginia Landmarks Register on November 5, 1968. It was also listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and as a National Historic Landmark, on August 11, 1969.[173] The American Battlefield Trust and its partners have preserved more than 729 acres of the Cedar Creek battlefield in 19 different transactions since 1996.[174]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ On November 24, Sheridan's report for August 10 through November 16 listed the capture or killing of over 41,000 animals, and over 500,000 bushels of wheat and corn. He destroyed 81 mills and 1,200 barns.[21]

- ↑ Grant preferred that Sheridan destroy the railroad lines near Charlottesville and disable the James River and Kanawha Canal that led to Richmond.[22] Sheridan believed that the logistics involved with taking his army to Charlottesville would be difficult, and worked on the goal to make the Valley unable to support Lee's army.[22]

- ↑ The National Park Service says 31,945 Union forces were engaged for the Union in the battle.[29]

- ↑ The Third Brigade of the 1st Division did not engage because it was in Winchester at the time of the battle.[35]

- ↑ Emory is also listed as a Brevet Major General in the Official Records.[36]

- ↑ The Third Brigade of the 1st Division was not engaged in the battle because it was guarding wagon trains.[36]

- ↑ Major portions of Crook's command came from what had been the VIII Corps, causing his command to be labeled as such for simplicity.[41] However, Army of West Virginia was the correct name, and both Sheridan and Crook used that name in their reports.[42][43]

- ↑ Crook is listed as a brevet major general in the official records for the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864.[45] However, he was not promoted to major general until October 21, 1864.[46]

- ↑ The Second Brigade of Crook's 1st Division was in Winchester at the time of the battle, and therefore did not engage.[45]

- ↑ Despite the title used by Crook and Sheridan, Crook's force was only the size of a typical division of the time.[41] Its two divisions, led by colonels instead of brigadier generals, were the size of brigades.[41]

- ↑ The source for Early's 21,102 effectives uses a 10/31/1864 field inspection for infantry, adds Cedar Creek losses, and adds cavalry and artillery.[48] The American Battlefield Trust says 21,000 Confederate forces were engaged.[49] The National Park Service says 15,265 Confederate men engaged.[29] Another study believes Early had about 14,000 effectives.[50]

- ↑ Powell's raid lasted from October 11 through October 14. Powell moved through Chester Gap and as far south as Sperryville before returning. This was 35 miles (56 km) short of Gordonsville. He captured a member of Mosby's Rangers, who was hanged, and destroyed property.[60][61]

- ↑ The Battle of Hupp's Hill is considered a Confederate victory.[64] Casualties included Confederate Brigadier General James Conner (severely wounded) and Union Colonel William D. Wells (mortally wounded).[65]

- ↑ Temporary Union commander Wright had failed to follow Sheridan's suggestion that he move Powell's cavalry from Front Royal to Crook's left, leaving the Union left unprotected.[73]

- ↑ Sources vary on the exact time the attacks began. Historian Jeffry Wert wrote that Kershaw attacked around 5:40 am, and Gordon attacked shortly afterwards.[86]

- ↑ Of the nine full infantry regiments present in Thoburn's Division, all were "wrecked beyond temporary repair" except the 116th Ohio and 123rd Ohio.[87]

- ↑ Du Pont later received the Medal of Honor and a brevet promotion to lieutenant colonel in the regular army for his efforts at Cedar Creek.[87][89]

- ↑ Colonel Kitching's wound would cause his death in January 1865.[94]

- ↑ The fortification described by the report of Brigadier General Henry W. Birge was called an earthworks.[96] Historian Thomas A. Lewis called the fortification a "formidable breastworks".[92]

- ↑ Historian Jeffry Wert uses 7:30 am for the attack time, but notes that descriptions of this portion of the battle reflect uncertainty—and few Confederate accounts exist.[107] Joseph Whitehorne uses 7:15 am for Kershaw's attack.[108] Keifer's report does not list an attack time.[109]

- ↑ One historian, noted that "Getty was one of the best commanders in the army and his men were some of the finest soldiers."[111] The historian also noted that Ramseur made a mistake by using piecemeal attacks against an entrenched opponent.[113]

- ↑ Whitehorne describes the halt as before 10:30 am.[108] Wert states that the pause started close to 10:30 am, but that facts destroy the assertion of a fatal halt.[127] Bohanan says the fatal halt was the afternoon lull that lasted from 1:00 pm until 4:00 pm.[128]

- ↑ With the exception of very-long range fighting, the seven-shot Spencer carbine used by the Union cavalry was a considerable advantage over the single-shot firearms used by the Confederate army.[129]

- ↑ Although Dwight had been under arrest, Sheridan reinstated him during the afternoon.[51] Grover, who had been wounded earlier, returned to command for the attack.[132]

- ↑ Wofford was not at the battle because he was recovering from a fall from his horse. Whitehorne identifies the commander of Wofford's Brigade as Colonel Henry P. Sanders.[140] The Official Records identify the commander, as of October 31, 1864, as Colonel C. C. Sanders.[141]

- ↑ Another source says Early lost "nearly all his transport", 18 Union artillery pieces were recaptured, and 25 to 30 Confederate artillery pieces were captured.[148] The American Battlefield Trust lists casualty totals of 5,764 for the Union and 3,060 for the Confederates.[149]

- ↑ Many of the Union's soldiers were on three-year enlistments that expired during 1864.[161] Replacing casualties and those that did not reenlist was difficult, and deserters were a problem. In addition, many soldiers were needed simply to guard conquered territory.[161] The political party of Lincoln's opponent in the election, George B. McClellan, wanted to negotiate an end to the war.[160] Confederate leaders were aware of these issues, and believed that if the Confederate army could perform well until McClellen was elected, they might be able to negotiate independence.[162] Historian Mark E. Neely Jr. believes that if McClellan won, slavery would have continued after the war.[160]

Citations

- ↑ Chernow 2017, pp. 335–336

- ↑ Chernow 2017, p. 356

- ↑ Chernow 2017, p. 357

- ↑ Whisonant 2015, p. 157

- ↑ Gallagher 2006, p. ix

- ↑ Gallagher 2006, p. 16

- ↑ "Lynchburg Campaign- June 14 - June 22, 1864". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- ↑ "Battle Detail - Kernstown II". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- ↑ "Battle of Monocacy, July 9, 1864". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- ↑ "Fort Stevens". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- ↑ Gallagher 2006, p. xii

- ↑ Chernow 2017, p. 431

- ↑ "Sheridan Takes Command in the Shenandoah Valley". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- ↑ Gallagher 2006, p. 14

- ↑ "Again into the Valley of Fire". American Battlefield Trust. 17 September 2014. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ↑ Lewis 1997, pp. 50–51

- ↑ Lewis 1997, p. 51

- ↑ Lowe & United States National Park Service, Interagency Resources Division 1992, p. 40

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 30

- ↑ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893b, pp. 307–308

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 37

- 1 2 3 4 Lewis 1997, pp. 51–52

- ↑ Early & Early 1912, p. 432

- 1 2 Early & Early 1912, p. 433

- 1 2 Early & Early 1912, p. 435

- 1 2 3 Wert 2010, p. 161

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 164

- 1 2 Whitehorne & Center of Military History, United States Army 1992, pp. 11–12

- 1 2 "Battle Detail - Cedar Creek". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ↑ Whitehorne & Center of Military History, United States Army 1992, pp. 7–8

- ↑ Wert 2010, pp. 308–309

- 1 2 3 Wert 2010, p. 198

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 18

- 1 2 3 4 5 Whitehorne & Center of Military History, United States Army 1992, p. 12

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 125

- 1 2 Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 127

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 20

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, pp. 129–130

- ↑ Whitehorne & Center of Military History, United States Army 1992, pp. 12–13

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 22

- 1 2 3 Lewis 1997, p. 95

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 115

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 360

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, pp. 128–129

- 1 2 Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 128

- ↑ "George Crook". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 171

- 1 2 3 Whitehorne & Center of Military History, United States Army 1992, p. 15

- ↑ "Cedar Creek - Belle Grove". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 2021-12-28.

- ↑ Gallagher 2006, p. 9

- 1 2 3 4 Wert 2010, p. 230

- ↑ "The Best Staff Officers in the Army - James Longstreet and His Staff of the First Corps" (PDF). National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ↑ Lewis 1997, p. 103

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 566

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 559

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 567

- ↑ Miller 2006, p. 135

- ↑ Wert 2010, pp. 165–166

- 1 2 Wert 2010, p. 166

- ↑ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893b, pp. 345–346

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 167

- ↑ Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1893b, pp. 346–347

- 1 2 3 Starr 2007, p. 304

- 1 2 3 "Battle of Hupp's Hill". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- 1 2 Wert 2010, p. 168

- ↑ Lewis 1997, p. 96

- 1 2 Wert 2010, p. 169

- ↑ Sheridan 1888, p. 60

- ↑ Sheridan 1888, p. 62

- ↑ Sheridan 1888, pp. 63–64

- ↑ Sheridan 1888, p. 66

- ↑ Lewis 1997, p. 106

- ↑ Starr 2007, p. 305

- ↑ Starr 2007, pp. 306–307

- ↑ Lewis 1997, p. 107

- ↑ Starr 2007, p. 307

- 1 2 3 Wert 2010, p. 175

- ↑ Starr 2007, pp. 307–308

- ↑ Lewis 1997, p. 172

- 1 2 Starr 2007, p. 308

- 1 2 3 4 5 Whitehorne & Center of Military History, United States Army 1992, p. 16

- ↑ Lewis 1997, p. 161

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 613

- ↑ Whitehorne & Center of Military History, United States Army 1992, p. 17

- 1 2 Lewis 1997, p. 169

- 1 2 3 Wert 2010, p. 185

- 1 2 3 Wert 2010, p. 183

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, pp. 413–416

- ↑ "U.S. Civil War - U.S. Army - Henry Algernon du Pont". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 374

- ↑ Wert 2010, pp. 185–186

- 1 2 Lewis 1997, p. 175

- 1 2 Wert 2010, p. 186

- 1 2 Lewis 1997, p. 174

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 187

- 1 2 3 Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 322

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 192

- ↑ Lewis 1997, p. 173

- ↑ Whitehorne & Center of Military History, United States Army 1992, p. 18

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 195

- ↑ Bohannon 2006, pp. 62–63

- 1 2 Bohannon 2006, p. 64

- 1 2 Wert 2010, p. 197

- 1 2 Early & Early 1912, p. 444

- ↑ Early & Early 1912, p. 445

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 196

- ↑ Wert 2010, pp. 203–204

- 1 2 3 Whitehorne & Center of Military History, United States Army 1992, p. 20

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, pp. 225–230

- ↑ Wert 2010, pp. 204–205

- 1 2 Wert 2010, p. 205

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 211

- 1 2 Wert 2010, p. 208

- 1 2 Starr 2007, p. 311

- ↑ Sheridan 1888, pp. 66–67

- ↑ Sheridan 1888, pp. 68–69

- ↑ Sheridan 1888, pp. 70–71

- ↑ Sheridan 1888, pp. 71–72

- ↑ Sheridan 1888, pp. 74–75

- ↑ Starr 2007, p. 312

- ↑ Sheridan 1888, pp. 76–77

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 223

- ↑ Whitehorne & Center of Military History, United States Army 1992, p. 21

- ↑ Lewis 1997, p. 204

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 212

- 1 2 Starr 2007, p. 310

- 1 2 Wert 2010, p. 216

- 1 2 3 4 Bohannon 2006, p. 66

- ↑ "CivilWar@Smithsonian - Weapons - Spencer Carbine". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2022-04-02.

- ↑ Lewis 1997, p. 223

- 1 2 3 Starr 2007, p. 316

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 231

- ↑ Starr 2007, p. 315

- ↑ Wert 2010, pp. 231–232

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 235; "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form - Thorndale Farm". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved January 4, 2024.; "034-0081 Thorndale Farm". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ↑ Starr 2007, pp. 316–317

- 1 2 Starr 2007, p. 317

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 234

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 235

- ↑ Whitehorne & Center of Military History, United States Army 1992, p. 13

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 913

- 1 2 Wert 2010, p. 236

- ↑ Whitehorne & Center of Military History, United States Army 1992, pp. 21–23

- 1 2 Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 137

- 1 2 Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 54

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 55

- 1 2 Wert 2010, p. 246

- 1 2 Starr 2007, p. 318

- ↑ "Cedar Creek Battlefield". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ↑ Starr 2007, p. 321

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 242

- ↑ "Medal of Honor at Cedar Creek". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

- ↑ Starr 2007, p. 320

- 1 2 3 4 Starr 2007, p. 313

- ↑ "Phil Sheridan's Ride to the Front, October 19, 1864 [See Next Page]". Harper's Weekly. New York, New York: Harper and Brothers. November 5, 1864. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ↑ Gallagher 2006, pp. 23–24

- ↑ Lewis 1997, p. 162

- ↑ Bohannon 2006, p. 77

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 249

- 1 2 3 "Lincoln, Grant, and the 1864 Election". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- 1 2 3 McPherson 1988, pp. 719–720

- ↑ McPherson 1988, p. 721

- ↑ Starr 2007, pp. 319–320

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 248

- ↑ Gallagher 2006, p. 28

- ↑ "General Phillip H. Sheridan Statue". DC Preservation League. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 247

- ↑ Wert 2010, p. 250

- ↑ Wert 2010, pp. 250–251

- ↑ "Waynesboro". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- ↑ "Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park Virginia". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- ↑ "Shenandoah Velley - Cedar Creek & Belle Grove National Historical Park". Virginia is for Lovers. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ↑ "034-0002 Cedar Creek Battlefield and Belle Grove". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ↑ "Cedar Creek Battlefield". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

References

- Ainsworth, Fred C.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1902). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies – Series I Volume XLIII Part I – Additions and Corrections, Chapter LV. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 427057. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- Bohannon, Keith S. (2006). ""The Fatal Halt" vs. "Bad Conduct": John B. Gordon, Jubal A. Early, and the Battle of Cedar Creek". In Gallagher, Gary W. (ed.). The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 56–84. ISBN 978-0-80783-005-5. OCLC 62281619.

- Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-0-52552-195-2. OCLC 989726874.

- Davis, George B.; Perry, Leslie J.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1893b). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies – Series I Volume XLIII Part II – Correspondence, Etc. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 427057. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- Du Pont, Henry A. (1925). The Campaign of 1864 in the Valley of Virginia and the Expedition to Lynchburg. New York: National Americana Society. OCLC 1667090. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- Early, Jubal A.; Early, Ruth H. (1912). Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early, C.S.A. Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War Between the States. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co. ISBN 978-1-46819-215-5. OCLC 1370161. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- Gallagher, Gary W. (2006). "Two Generals and a Valley: Philip H. Sheridan and Jubal A. Early in the Shenandoah". In Gallagher, Gary W. (ed.). The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 3–33. ISBN 978-0-80783-005-5. OCLC 62281619.

- Lewis, Thomas A. (1997). The Guns of Cedar Creek. Strasburg, Virginia: Heritage Associates. OCLC 42688338.

- Lowe, David W.; United States National Park Service, Interagency Resources Division (1992). Study of Civil War Sites in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia: Pursuant to Public Law 101-628. Washington, DC: United States National Park Service, Interagency Resources Division. OCLC 1225730136. Retrieved 2021-12-23.

- McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19503-863-7. OCLC 805415782.

- Miller, William J. (2006). "Never has There Been a More Complete Victory". In Gallagher, Gary W. (ed.). The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 134–160. ISBN 978-0-80783-005-5. OCLC 62281619.

- Sheridan, Philip Henry (1888). Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan, General, United States Army – Volume II. New York: Charles L. Webster & Company. OCLC 703942811. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- Starr, Stephen Z. (2007). Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071329-1-3. OCLC 153582839.

- Wert, Jeffry D. (2010). From Winchester to Cedar Creek: The Shenandoah Campaign of 1864. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-80932-972-4. OCLC 463454602.

- Whisonant, Robert C. (2015). Arming the Confederacy : How Virginia's Minerals Forged the Rebel War Machine. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-14508-2. OCLC 903929889.

- Whitehorne, Joseph W.A.; Center of Military History, United States Army (1992). The Battle of Cedar Creek: Self-Guided tour. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. ISBN 978-0-16026-854-0. OCLC 22861511. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

External links

- Cedar Creek – Belle Grove – American Battlefield Trust

- Animated map of the Battle of Cedar Creek – American Battlefield Trust

- Battle of Cedar Creek – National Park Service

- Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park – National Park Service