43°39′09″N 79°22′54″W / 43.65250°N 79.38167°W

| Battle of York | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

Battle of York by Owen Staples, 1914. The American fleet before the capture of York. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Ojibwe |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

300 regulars 300 militia 40–50 Natives |

1,700 regulars[2] 14 armed vessels | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

82 killed 112 wounded (including 69 wounded prisoners) 274 captured 7 missing[3] |

55 killed 265 wounded[1] | ||||||

The Battle of York was a War of 1812 battle fought in York, Upper Canada (today's Toronto, Ontario, Canada) on April 27, 1813. An American force, supported by a naval flotilla, landed on the western lakeshore and captured the provincial capital after defeating an outnumbered force of regulars, militia and Ojibwe natives under the command of Major General Roger Hale Sheaffe, the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada.

After Sheaffe's forces were defeated, he ordered his surviving regulars to withdraw to Kingston, abandoning the militia and civilians. The Americans captured the fort, town, and dockyard. They themselves suffered casualties, including force leader Brigadier General Zebulon Pike and others killed when the retreating British blew up the fort's magazine.[4] After the American forces carried out several acts of arson and looting, they seized ordnances and supplies from the settlement and subsequently withdrew from the town weeks later.

Although the Americans won a clear victory, the battle did not have decisive strategic results as York was a less important objective in military terms than Kingston, where the British armed vessels on Lake Ontario were based.

Background

.jpg.webp)

York, the capital of Upper Canada, stood on the north shore of Lake Ontario. During the War of 1812, the lake was both the front line between Upper Canada and the United States, and also served as the principal British supply line from Quebec to the various forces and outposts to the west. At the start of the war, the British had a small naval force, the Provincial Marine, with which they seized control of Lake Ontario, and Lake Erie. This made it possible for Major General Isaac Brock, who led British forces in Upper Canada, to gain several important victories in 1812 by shifting his small force rapidly between threatened points to defeat disjointed American attacks individually.[5]

The United States Navy appointed Commodore Isaac Chauncey to regain control of the lakes. He created a squadron of fighting ships at Sackett's Harbor, New York by purchasing and arming several lake schooners and laying down purpose-built fighting vessels.[6] However, no decisive action was possible before the onset of winter, during which the ships of both sides were confined to their harbours by ice.[7] To match Chauncey's shipbuilding efforts, the British laid down the sloop-of-war, Wolfe, at Kingston and Sir Isaac Brock, at York Naval Shipyards.

Prelude

American planning

On January 13, 1813, John Armstrong Jr. was appointed United States Secretary of War. He quickly assessed the situation on Lake Ontario and devised a plan by which a force of 7,000 regular soldiers would be concentrated at Sackett's Harbor on April 1. Working together with Chauncey's squadron, this force would capture Kingston before the Saint Lawrence River thawed and substantial British reinforcements could arrive in Upper Canada. The capture of Kingston and the destruction of the Kingston Royal Naval Dockyard together with most of the vessels of the Provincial Marine, would make almost every British post west of Kingston vulnerable if not untenable.[8] After Kingston was captured, the Americans would then capture the British positions at York and Fort George, at the mouth of the Niagara River.

Armstrong conferred with Major General Henry Dearborn, commander of the American Army of the North, at Albany, New York during February. Both Dearborn and Chauncey agreed with Armstrong's plan at this point, but they subsequently had second thoughts. That month, Lieutenant General Sir George Prévost, the British Governor General of Canada, travelled up the frozen Saint Lawrence to visit Upper Canada. This visit was made necessary because Major General Roger Hale Sheaffe, who had succeeded Brock as Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, was ill and unable to perform his various duties. Prévost was accompanied only by a few small detachments of reinforcements, which participated in the Battle of Ogdensburg en route. Nevertheless, both Chauncey and Dearborn believed that Prévost's arrival indicated an imminent attack on Sackett's Harbor, and reported that Kingston now had a garrison of 6,000 or more British regulars.

Even though Prévost soon returned to Lower Canada, and deserters and pro-American Canadian civilians reported that the true size of Kingston's garrison was 600 regulars and 1,400 militia,[9] Chauncey and Dearborn chose to accept the earlier inflated figure. Furthermore, even after two brigades of troops under Brigadier General Zebulon Pike reinforced the troops at Sackett's Harbor after a gruelling winter march from Plattsburgh, the number of effective troops available to Dearborn fell far short of the 7,000 planned, mainly as a result of sickness and exposure. During March, Chauncey and Dearborn recommended to Armstrong that when the ice on the lake thawed, they should attack the less well-defended town of York instead of Kingston. Although York was the provincial capital of Upper Canada, it was far less important than Kingston as a military objective. Historians such as John R. Elting have pointed out that this change of plan effectively reversed Armstrong's original strategy, and by committing the bulk of the American forces at the western end of Lake Ontario, it left Sackett's Harbor vulnerable to an attack by British reinforcements arriving from Lower Canada.

Armstrong, by now back in Washington, nevertheless acquiesced in this change of plan as Dearborn might well have better local information.[10] Armstrong also believed that an easy victory at York would provide the government with a significant propaganda coup, as well as bolster support for the Democratic-Republican Party for the gubernatorial election in New York.[11]

The attack was originally planned to commence in early April, although a long winter delayed the attack on York by several weeks, threatening the political value of such an attack. In an attempt to overcome these delays, Democratic-Republicans supporters circulated proclamations of victory prior to the battle to the New York electorate.[11] The American naval squadron first attempted to depart from Sackets Harbor on April 23, 1813, although an incoming storm forced the squadron back to harbour, in order to wait out the storm. The squadron finally departed on April 24, 1813.[12]

British preparations

The town was not heavily fortified, with insufficient resources preventing the construction of necessary works needed to adequately defend it.[11] As a result, Sheaffe had instructed government officials in early April 1813 to hide legislative papers in the forest and fields behind York, to ensure they would not be seized in the event of an attack.[11]

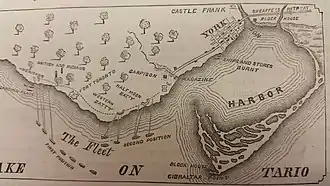

York's defences included the town's blockhouse situated near the Don River east of the town, the blockhouses at Fort York to the west, and another blockhouse at Gibraltar Point.[12] The settlement was also defended by three batteries at the fort and the nearby "Government House Battery" which mounted two 12-pounder guns. Another crude battery, known as the Western Battery, was located 1.6 kilometres (1 mi) west of the fort, in present-day Exhibition Place.[12] It contained two obsolete 18-pounder guns, which originated from earlier conflicts and had been disabled by having their trunnions removed, but they were fixed to crude log carriages and could still be fired.[2]

Fort York was also defended by a western wall and a small unarmed earthwork between the fort and the Western Battery.[12] About a dozen cannons, including older condemned models, were mounted in these positions, in addition to two 6-pounders on field carriages.[12] Further west were the ruins of Fort Rouillé, and the Half Moon Battery, neither of which was in use.[9]

Sheaffe was at York to conduct public business. He was originally scheduled to leave the settlement for Fort George but had postponed his departure due to suspicions of an American assault on York.[13] His regulars, most of whom were also passing through York en route to other posts,[13] consisted of two companies (including the grenadier company) of the 1st battalion 8th Regiment of Foot, a company of the Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles, a company-sized detachment of the Royal Newfoundland Fencibles,[2] a small squad from the 49th Regiment of Foot, and thirteen soldiers from the Royal Artillery.[12] There were also 40 or 50 Mississaugas and Ojibwe warriors, and the Canadian militia.

The American naval squadron was spotted by British sentries posted at the Scarborough Bluffs on April 26, who alerted the town and its defenders using flag signals and signal guns.[12] The Militia was ordered to assemble, but only 300 of the 1st and 3rd Regiments of the York Militia, and the Incorporated Militia,[12] could be mustered at short notice. Sheaffe expected the Americans to launch a two-pronged attack, with the main American landing to the west of Fort York, and another landing in Scarborough to cut off a potential retreat to Kingston. To counteract this, Sheaffe concentrated most of his regulars, the Native warriors and a small number of militiamen at Fort York, while most of the militia and the companies of the 8th Regiment of Foot positioned themselves at the town's blockhouse.[14]

Order of Battle

| British and Native order of battle | American order of battle |

|---|---|

|

British Army: Major General Roger Hale Sheaffe

|

Army of the North: Major General Henry Dearborn

|

Battle

The Americans fleet appeared off of York late on April 26. Chauncey's squadron consisted of a ship-rigged corvette, a brig and twelve schooners. The embarked force commanded by Brigadier General Zebulon Pike numbered between 1,600 and 1,800, mainly from the 6th, 15th, 16th and 21st U.S. Infantry, and the 3rd U.S. Artillery fighting as infantry.[16] Dearborn, the overall army commander, remained aboard the corvette Madison during the action.

Early on April 27, the first American wave of boats, carrying 300 soldiers of Major Benjamin Forsyth's company of the U.S. 1st Rifle Regiment, landed about 6.4 kilometres (4 mi) west of the town, supported by some of Chauncey's schooners firing grapeshot. The American force intended to land at a clear field, west of Fort York, but strong winds pushed their landing craft 3.2 kilometres (2 mi) west of their desired landing site, towards a wooded coastline.[17] Forsyth's riflemen were opposed only by Native warriors, led by James Givins of the British Indian Department, and the grenadier company of the 8th Regiment of Foot, who were dispatched to the area by Sheaffe.[17] Only the Natives initially engaged the American landing. With American cannon fire threatening the roads on the waterfront, the British units dispatched from Fort York had to traverse through the forest behind the waterfront; and were unable to reach the landing site before the Americans started their landings.[14]

Sheaffe had also ordered a company of the Glengarry Light Infantry to support the Natives at the landing, but they became lost in the outskirts of the town, having been misdirected by Major-General Aeneas Shaw, the Adjutant General of the Canadian Militia, who took some of the militia north onto Dundas Street to prevent any wide American flanking maneuver.[19] After it became apparent that no landing would occur east of the settlement, Sheaffe recalled the companies of the 8th Regiment of Foot from the town's blockhouse.[14]

As the landings progressed, the British and Native force was outflanked and began to fall back into the woods. The U.S. 15th Infantry Regiment was the second American unit to land, with bayonets fixed, under a hail of fire, shortly followed by Pike, who assumed personal command of the landing.[20] Sheaffe arrived with the rest of the 8th Regiment of Foot, the Royal Newfoundland Fencibles, and a few dozen militiamen after the U.S. 15th Infantry Regiment had landed.[20] The grenadier company of the 8th Regiment of Foot charged them with the bayonet.[2] The grenadiers were already outnumbered and were repulsed with heavy loss. Pike ordered an advance by platoons, supported by two 6-pounder field guns, which steadily drove back Sheaffe's force. After Sheaffe failed to get the Fencibles to renew their advance, the British began to withdraw, with the newly arrived Glengarry Light Infantry covering the retreat.[20]

During these landings, the American naval squadron bombarded the four gun batteries defending York.[20] Chauncey's schooners, most of which carried a long 24-pounder or 32-pounder cannon, also bombarded the fort and Government House battery, with Chauncey himself directing them from a small boat. British return fire was ineffective.

The British tried to rally around the Western battery, but the battery's travelling magazine (a portable chest containing cartridges) exploded, apparently as the result of an accident.[21] This caused further loss (including 20 killed) and confusion among the British regulars, and they fell back to a ravine at Garrison Creek north of the fort, where the militia was forming up.[20] American forces advanced east towards the fort, and assembled themselves outside its walls, exchanging artillery fire with the fort.[22] The naval squadron also bombarded the fort, having re-positioned themselves directly south of the fort's stockade.[23] Sheaffe decided that the battle was lost and ordered the regulars to retreat, setting fire to the wooden bridge over the River Don east of the town to thwart pursuit. The militia and several prominent citizens were left "standing in the street like a parcel of sheep".[24] Sheaffe instructed the militia to make the best terms they could with the Americans, but without informing the senior militia officers or any official of the legislature, he also dispatched Captain Tito LeLièvre of the Royal Newfoundland[25] to set fire to the sloop-of-war HMS Sir Isaac Brock under construction at York's Naval Shipyard and to blow up the fort's magazine.[26][27] The two sides continued to exchange artillery fire until Sheaffe's withdrawal from the fort was complete.[28] The British had left the flag flying over the fort as a ruse, and the Americans assembling outside its walls assumed that the fort was still occupied.[28]

By 1:00 pm, the Americans were 200 yards (183 m) from the fort, and their artillery and the naval squadron were preparing to bombard it.[20] Pike was questioning a prisoner as to how many troops were defending the fort. Shortly after the bombardment began, the magazine (which contained over 74 tons of iron shells and 300 barrels of gunpowder and had been rigged by the British to explode) blew up. The explosion threw debris over a 500-yard (460 m) radius.[29][30] General Pike and 37 other American soldiers were killed by the explosion, which caused an additional 222 casualties.[31] Fearing a counterattack after the explosion, American forces regrouped outside the wall, and did not advance onto the abandoned fort until after the British regulars had left the settlement.[28]

Casualties

The American loss for the entire battle was officially reported as 52 killed and 254 wounded for the Army and 3 killed and 11 wounded for the Navy, for a total of 55 killed and 265 wounded. The majority of American casualties originated from the explosion at the fort's powder magazine. An archaeological dig in 2012 unearthed evidence that the destruction of the magazine and the impact it had on American soldiers was a result of poor position, and bad luck. The Americans just happened to be at the exact distance of the shock wave and its debris field.[32]

The British loss was officially reported by Sheaffe as 59 killed, 34 wounded, 43 wounded prisoners, 10 captured and seven missing, for a total of 153 casualties.[33] However, historian Robert Malcomson has found this return to be inaccurate: it did not include militia, sailors, dockyard workers or Native Americans and was incorrect even as to the casualties of the regulars. Malcomson demonstrates that the actual British loss was 82 killed, 43 wounded, 69 wounded prisoners, 274 captured and seven missing, for a total of 475 casualties.[34]

Surrender

Colonel William Chewett and Major William Allen of the 3rd York Regiment of militia tried to arrange a capitulation, assisted by Captain John Beverley Robinson, the acting Attorney General of Upper Canada. The process took time. The Americans were angry over their losses, particularly because they believed that the ship and fort had been destroyed after negotiations for surrender had already begun.[35] Nevertheless, Colonel Mitchell of the 3rd U.S. Artillery agreed to terms. While they waited for Dearborn and Chauncey to ratify the terms, the surrendered militia was held prisoner in a blockhouse without food or medical attention for the few wounded. Forsyth's company of the 1st U.S. Rifle Regiment was left as a guard in the town. At this stage, few Americans had entered the town.

The next morning, the terms had still not been ratified, since Dearborn had refused to leave the corvette Madison. When he eventually did, Reverend John Strachan (who held no official position other than Rector of York at the time) first brusquely tried to force him to sign the articles for capitulation on the spot, then accused Chauncey to his face of delaying the capitulation to allow the American troops licence to commit outrages.[36] Eventually, Dearborn formally agreed to the articles for surrender. The official terms of surrender permitted civil servants to continue carrying out their duties, and surgeons to treat British wounded.[37] As a part of the terms of surrender, any troops remaining in York became prisoners of war, although those serving in the militia were "paroled," and allowed to return home so long as they do not rejoin the conflict until an official prisoner exchange had secured their "release".[37] Members of the York Militia were ordered to relinquish their arms, and proceed to Fort York garrison. The officers of the militia were subsequently released on "parole," although the rest of the militia remained imprisoned for two days.[38] Kept without food, water, or medical attention, the imprisoned militia was eventually released at the behest of Strachan.[38]

The Americans took over the dockyard, where they captured a brig (Duke of Gloucester) in a poor state of repair, and twenty 24-pounder carronades and other stores intended for the British squadron on Lake Erie. Sir Isaac Brock was beyond salvage. The Americans had missed another ship-rigged vessel, Prince Regent, which carried 16 guns, as she sailed for Kingston to collect ordnance two days before the Americans had been sighted.[39] The Americans also demanded and received several thousand pounds in Army Bills, which had been in the keeping of Prideaux Selby, the Receiver General of Upper Canada, who was mortally ill.

Burning of York

Between April 28 and 30, American troops carried out many acts of plunder. Some of them set fire to the buildings of the Legislative Assembly, and Government House, home to the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada. It was alleged that the American troops had found a scalp there,[40] though folklore had it that the "scalp" was actually the Speaker's wig. The Parliamentary mace of Upper Canada was taken back to Washington and was only returned in 1934 as a goodwill gesture by President Franklin Roosevelt.[41] The Printing Office, used for publishing official documents as well as newspapers, was vandalized and the printing press was smashed. Other Americans looted empty houses on the pretext that their absent owners were militia who had not given their parole as required by the articles of capitulation. The homes of Canadians connected with the Natives, including that of James Givins, were also looted regardless of their owners' status.[42] Before they departed from York, the Americans razed most of the structures in the fort, except the barracks.[43]

During the looting, several officers under Chauncey's command took books from York's first subscription library. After finding out his officers were in possession of looted library books, Chauncey had the books packed in two crates, and returned them to York, during the second incursion in July. However, by the time the books arrived, the library had closed, and the books were auctioned off in 1822.[44] Several looted items ended up in the possession of the locals. Sheaffe later alleged that local settlers had unlawfully acquired government-owned farming tools or other stores looted and discarded by the Americans, and demanded that they be handed back.[45]

The looting of York occurred in spite of Pike's earlier orders that all civilian property be respected and that any soldier convicted of such transgressions would be executed.[17] Dearborn similarly emphatically denied giving orders for any buildings to be destroyed and deplored the worst of the atrocities in his letters, but he was nonetheless unable or unwilling to rein in his soldiers. Dearborn himself was embarrassed by the looting, as it made a mockery of the terms of surrender he arranged. His soldiers' disregard for the terms he arranged, and local civil leaders' continued protest against them, made Dearborn eager to leave York as soon as all the captured stores were transported.[46]

Aftermath

The Americans occupied the town for nearly two weeks. They sent the captured military stores, including 20 artillery pieces,[29] away on May 2 but were then penned in York harbour by a gale. Chauncey's vessels were so overcrowded with troops that only half of them could go below decks to escape the rain at any time.[47] They left York on May 8, departing for the Niagara peninsula.[48] where they required several weeks to recuperate. Sheaffe's troops endured an equally miserable fourteen-day retreat overland to Kingston.[35]

Around 300 to 400 Iroquois warriors assembled and marched towards York shortly after the battle, in an effort to launch an attack on the American forces there.[48] The Iroquois were approximately 50 kilometres (31 mi) west of York, in present-day Burlington, when they learned that the Americans had departed York; resulting in the expedition to be called off.[48]

Effects on the war

Many members of the Provincial Assembly and other prominent citizens severely criticized Sheaffe, both for his conduct generally and during the fighting at York. For example, Militia officers Chewitt and Allan, the Reverend Strachan and others wrote to Governor General Prévost on May 8, that Sheaffe "kept too far from his troops after retreating from the woods, never cheered or animated them, nor showed by his personal conduct that he was hearty in the cause."[49] Sheaffe lost his military and public offices in Upper Canada as a result of his defeat.

However, the Americans had not inflicted crippling damage on the Provincial Marine on Lake Ontario, and they admitted that by preserving his small force of regulars rather than sacrificing them in a fight against heavy odds, Sheaffe had robbed them of decisive victory. Secretary of War Armstrong wrote, "[W]e cannot doubt but that in all cases in which a British commander is compelled to act defensively, his policy will be that adopted by Sheaffe – to prefer the preservation of his troops to that of his post, and thus carrying off the kernel leave us the shell."[50]

The effects of the capture of York were probably most significant on Lake Erie, since the capture of the ordnance and supplies destined for the British squadron there contributed to the defeat of the British squadron at the Battle of Lake Erie.[46] However, most of the naval supplies captured were not used by the Americans, who abandoned a portion of the captured goods before they departed from York, while the remaining supplies were set on fire during the Second Battle of Sacket's Harbor in May 1813.[51]

Societal consequences

As the American attack on York occurred on the first of New York's three-day election period, the battle did not directly benefit the Democratic-Republic Party as Armstrong had originally envisioned.[52] However, early proclamations of victory issued prior to the battle, did contribute to the reelection of Daniel D. Tompkins, the Democratic-Republican candidate for the Governor of New York.[52]

According to Pierre Berton, the battle, and occupation of York served as a watershed moment for the settlers of York. Those who fought the Americans became celebrated in the local community, while those who aided the occupation were viewed by the community as traitors.[53] The documentary film Explosion 1812 argues that the battle had a much greater impact than previously assumed. The mistreatment by US forces of the civilian Canadian population, dogged resistance by militia and the burning of British symbols and buildings after the battle led to a hardening of Canadian popular opinion against the United States.[32]

Several commentators viewed the American transgressions at York as justification for the British Burning of Washington later in the war. Prévost wrote that "as a just retribution, the proud capital at Washington has experienced a similar fate".[54] Strachan wrote to Thomas Jefferson that the damage to Washington "was a small retaliation after redress had been refused for burnings and depredations, not only of public but private property, committed by them in Canada".[55]

Later attacks

Second incursion, July 1813

Chauncey and Dearborn subsequently won the Battle of Fort George on the Niagara peninsula, but they had left Sacket's Harbor defended only by a few troops, mainly militia. When reinforcements from the Royal Navy commanded by Commodore James Lucas Yeo arrived in Kingston, Yeo almost immediately embarked some troops commanded by Prévost and attacked Sackett's Harbor. Although the British were repelled by the defenders at the Second Battle of Sacket's Harbor, Chauncey immediately withdrew into Sacket's Harbor until mid-July, when a new heavy sloop-of-war had been completed.

Chauncey sortied again on July 21 with 13 vessels. Six days later, he embarked a battalion of 500 troops commanded by Colonel Winfield Scott at Niagara.[56] Chauncey sought to relieve the British-Native blockade of Fort George, by attacking British supply lines at Burlington Heights at the western end of Lake Ontario.[43] Winfield Scott's force disembarked east of the heights at Burlington Beach (present-day Burlington) on July 29 but found the defenders too well entrenched for any assault to be successful.[43]

Anticipating Chauncey's intentions, Major-General Francis de Rottenburg, Sheaffe's successor as Lieutenant Governor, ordered the bulk of the troops at York to Burlington Heights.[57][58] However, this left York largely undefended, as most of its militia were still on parole.[57] The American squadron proceeded to York in order to seize food stores to feed its soldiers. The last remaining troop in York, members of the 19th Light Dragoons, collected the military supplies they could carry and withdrew along the Don River.[57] The American landing of 340 men at York was unopposed, with the American force burning the barracks at the fort and the military fuel yards, and looting several properties.[57] They also seized 11 batteaux, 5 cannons and some flour, before reembarking on their ships, leaving the settlement later that night.[57] The library books that were looted from the battle in April 1813, were returned to the settlement during the second incursion into York.

The Ontario Heritage Foundation erected a plaque in 1968 near the entrance to Coronation Park, Exhibition Place, Lake Shore Boulevard, in commemoration of the event. The plaque reads:

On the morning of July 31, 1813, a U.S. invasion fleet appeared off York (Toronto) after having withdrawn from a planned attack on British positions at Burlington Heights. That afternoon 300 American soldiers came ashore near here. Their landing was unopposed: there were no British regulars in town, and York's militia had withdrawn from further combat in return for its freedom during the American invasion three months earlier. The invaders seized food and military supplies, then re-embarked. The next day they returned to investigate collaborators' reports that valuable stores were concealed up the Don River. Unsuccessful in their search, the Americans contented themselves with burning military installations on nearby Gibraltar Point before they departed.[59]

Third incursion, August 1814

In the months after the second American incursion into York, the defences around the harbour were significantly improved, as the British needed to protect a four-vessel squadron that would be stationed at the town's harbour.[60] On August 6, 1814, the American Lake Ontario squadron pursued HMS Magnet, before its captain set fire to the ship, preventing its capture.[60] Suspecting the ship sailed from York, the American naval squadron made its way to the settlement in order to evaluate the situation, and discover if any more ships could be captured there.[60]

Arriving near York's harbour, the American squadron dispatched USS Lady of the Lake to negotiate under a white flag, in a ploy to evaluate the town's defences. However, the militia stationed at Fort York opened fire at the schooner, which returned fire, before withdrawing to rejoin the American squadron.[61] The 8th Regiment of Foot, and the 82nd Regiment of Foot were sent to York in an effort to bolster the town's defences. The American squadron did not attempt to engage the newly built defences, although they remained outside York's harbour for the next three days before sailing away.[61]

Legacy

The burning and looting of York after the battle, along with the destruction of other Upper Canadian settlements during the war, saw public opinions on Americans shift among the residents of Upper Canada. Historian, Charles Perry Stacey notes in the years before the war, American settlers had regularly settled into Upper Canada, with the colony essentially becoming a "transnational space," and the only distinction between Americans and Upper Canadians existing on paper.[62] However, in the years after the war, Stacey notes a "deep prejudice against the United States," had emerged amongst the colony's settlers.[62] Stacey further notes that the burning of York, and other American transgressions during the war, were later used by Canadian nationalists to create a national narrative that sees the "birth of the Canadian nation," as a result of the conflict.[62]

Several Canadian Army Reserve units perpetuate the linages of Fencibles, and militia units involved in the Battle of York, including the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders (Glengarry Light Infantry), the Queen's York Rangers (1st and 3rd regiments of the York Militia), and the Royal Newfoundland Regiment (Royal Newfoundland Fencibles).[63] Five active regular battalions of the United States Army (2-1 ADA, 1-2 Inf, 2-2 Inf, 1-5 Inf and 2-5 Inf) perpetuate the lineages of several American units engaged during the Battle of York (including Crane's Company, 3rd Regiment of Artillery, and the old 6th, 16th, and 21st Infantry Regiments). Within the British Army, the 8th Regiment of Foot is today perpetuated by the Duke of Lancaster's Regiment while the 49th Regiment of Foot is perpetuated by The Rifles Regiment.

On July 1, 1902, Walter Seymour Allward was commissioned to sculpt the Defence of York monument at the Fort York burial grounds. The monument was erected to commemorate those that fought in defence of York; as well as the British, Canadian, and Native warriors who fought in the War of 1812.[64]

On April 27, 2013, the City of Toronto government and the Canadian Armed Forces commemorated the 200th anniversary of the battle with a Presentation of Colours to the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment. The ceremony took place at Queen's Park, and was presided over by Prince Philip. The ceremony was followed by a military parade of 1,500 sailors and soldiers from the Canadian Army, and the Royal Canadian Navy; from Queen's Park to Fort York.[65] The ceremony and parade was organize in conjunction with other War of 1812 bicentennial commemorations held in Toronto, and the other municipalities in Ontario.[66] During the bicentennial celebrations, the City of Toronto Museum Services commissioned the creation of the exhibit Finding the Fallen: the Battle of York Remembered at Fort York. The exhibit attempts to document American, British (including the militia), and First Nations combatants that died during the battle.[67]

References

- 1 2 Cruikshank, p. 183

- 1 2 3 4 Hitsman 1995, p. 138.

- ↑ Malcomson 2008, p. 393.

- ↑ Peppiatt, Liam. "Chapter 31B: Fort York". Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto. Archived from the original on June 6, 2016. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ↑ "The Defence of Upper Canada, 1812" by C. P. Stacey, in Zaslow, pp. 12-20

- ↑ Roosevelt, Theodore (2004). The Naval War of 1812. New York: The Modern Library. pp. 86–87. ISBN 0-375-75419-9.

- ↑ "Alarum on Lake Ontario, 1812-1813" by J. Mackay Hitsman, in Zaslow, p.47

- ↑ Hitsman 1995, p. 136.

- 1 2 Charles W. Humphries, The Capture of York, in Zaslow, p. 254

- ↑ Elting 1995, p. 94.

- 1 2 3 4 Benn 1993, p. 49.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Benn 1993, p. 50.

- 1 2 Berton 2011, p. 41–42.

- 1 2 3 Benn 1993, p. 51.

- ↑ Hero of Oswego

- ↑ Colonel Ichabod Crane commanded Company B, 3rd U.S. Artillery.

- 1 2 3 Blumberg 2012, p. 82.

- ↑ Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 590.

- ↑ Charles W. Humphries, The Capture of York, in Zaslow, p. 255

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Blumberg 2012, p. 83.

- ↑ Hitsman, p. 332, fn

- ↑ Benn 1993, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Feltoe, Richard (2012). Redcoated Ploughboys: The Volunteer Battalion of Incorporated Militia of Upper Canada, 1813–1815. Dundurn. p. 81. ISBN 9781459700000.

- ↑ John Beikie, Sheriff of York, quoted in Charles W. Humphries, The Capture of York, in Zaslow, p. 258

- ↑ Malcomson 2008, p. 215.

- ↑ Hitsman 1995, p. 140.

- ↑ Malcomson 2008, p. 225.

- 1 2 3 Benn 1993, p. 56.

- 1 2 Blumberg 2012, p. 84.

- ↑ Stewart, Andrew M. (2008). "New Stories from Toronto's Old Fort York:Assets in Place" (PDF). Arch Notes. 13 (5): 10.

- ↑ Malcomson 1998, p. 107.

- 1 2 "War of 1812 explodes on TV". News.nationalpost.com. June 16, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ↑ Cruikshank, pp. 215–216

- ↑ Malcomson 1998, p. 393.

- 1 2 Elting 1995, p. 118.

- ↑ Charles W. Humphries, The Capture of York, in Zaslow, p. 261

- 1 2 Benn 1993, p. 58.

- 1 2 Benn 1993, p. 60.

- ↑ Forester, p. 124

- ↑ Charles W. Humphries, The Capture of York, in Zaslow, p. 264

- ↑ "The Mace – The Speaker". Speaker.ontla.on.ca. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ↑ Charles W. Humphries, The Capture of York, in Zaslow, p. 265

- 1 2 3 Benn 1993, p. 66.

- ↑ "War of 1812: The Battle of York". Toronto Public Library. 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- ↑ Charles W. Humphries, The Capture of York, in Zaslow, pp. 267–268

- 1 2 Berton 2011, p. 59.

- ↑ Hitsman 1995, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 Benn 1993, p. 62.

- ↑ Hitsman, pp. 140, 333(en)

- ↑ Charles W. Humphries, The Capture of York, in Zaslow, p. 269

- ↑ Benn 1993, p. 64.

- 1 2 Benn 1993, p. 63.

- ↑ Berton 2011, p. 60.

- ↑ Elting 1995, p. 220.

- ↑ Hitsman & Graves 1999, pp. 244–245.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Theodore (1999). The Naval War of 1812. New York: Modern Library. p. 131. ISBN 0-375-75419-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Benn 1993, p. 68.

- ↑ Elting, p. 99

- ↑ "DHH - Memorials Details Search Results". April 2, 2015. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Benn 1993, p. 72.

- 1 2 Benn 1993, p. 73.

- 1 2 3 Frentzos, Christos G.; Thompson, Antonio S. (2014). The Routledge Handbook of American Military and Diplomatic History: The Colonial Period to 1877. Routledge. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-3178-1335-4.

- ↑ "War Of 1812 Battle Honours". National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces. Government of Canada. September 14, 2012. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ↑ "Memorial 35091-026 Toronto, ON". Veterans Affairs Canada. Government of Canada. March 25, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ↑ Frisk, Adam (April 26, 2013). "Toronto marks Battle of York bicentennial". Global News. Corus Entertainment Inc. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ↑ "Bicentennial Commemoration Launch (2012)". The Friends of Fort York and Garrison Commons. 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ↑ Nickerson, Janice (2012). York's Sacrifice: Militia Casualties of the War of 1812. Dundurn. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4597-0595-1.

Bibliography

- Benn, Carl (1993). History Fort York, 1794–1993. Dundurn. ISBN 1-4597-1376-1.

- Berton, Pierre (2011). Flames Across the Border: 1813–1814. Doubleday Canada. ISBN 978-0-3856-7359-4.

- Blumberg, Arnold (2012). When Washington Burned: An Illustrated History of the War of 1812. Casemate. ISBN 978-1-6120-0101-2.

- Borneman, Walter R. (2004). 1812: The War That Forged a Nation. Harper Perennial, New York.

- Cruikshank, Ernest (1971) [1902]. The Documentary History of the Campaign upon the Niagara Frontier in the Year 1813. Part 1: January to June, 1813. New York: The Arno Press Inc. ISBN 0-405-02838-5.

- Elting, John R. (1995). Amateurs to Arms: A Military History of the War of 1812. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80653-3.

- Forester, C. S. (1956). The Age of Fighting Sail. New English Library. ISBN 0-939218-06-2.

- Hickey, Donald R. (1989). The War of 1812, A Forgotten Conflict. University of Illinois Press, Chicago and Urbana. ISBN 0-252-01613-0.

- Hitsman, J. Mackay (1995) [1965]. The Incredible War of 1812. Toronto: Robin Brass Studio. ISBN 1-896941-13-3.

- Hitsman, J. Mackay; Graves, Donald E. (1999). The Incredible War of 1812. Toronto: Robin Brass Studio. ISBN 1-896941-13-3.

- Latimer, Jon (2007). 1812: War with America. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02584-4.

- Malcomson, Robert (2008). Capital in Flames: The American Attack on York, 1813. Toronto: Robin Brass Studio. ISBN 978-1-896941-53-0.

- Malcomson, Robert (1998). Lords of the Lake:The Naval War on Lake Ontario 1812–1814. Robin Brass Studio, Toronto. ISBN 1-896941-08-7.

- Paine, Ralph Delahaye (2010) [1920]. The fight for a free sea: a chronicle of the War of 1812. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1920. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-59114-362-8.

- Zaslow, Morris (1964). The Defended Border. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada. ISBN 0-7705-1242-9.

- For more sources / further reading see Bibliography of early American naval history or Bibliography of the War of 1812

External links

![]() Media related to Battle of York at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of York at Wikimedia Commons