The presence of the Catholic Church in the Chinese province of Sichuan (formerly romanized as Szechwan or Szechuan in English; and Sutchuen, Setchuen, Setchoan or Sétchouan in French; Latin: Ecclesia Catholica in Seciuen or Secioan[1]) dates back to 1640, when two missionaries, Lodovico Buglio and Gabriel de Magalhães, through Jesuit China missions, entered the province and spent much of the 1640s doing evangelism.[2]

The Yongzheng edict of 1724 proscribed Christianity in the Qing empire and declared foreign missionaries personae non gratae. Catholics in Sichuan learned how to make do without ordained priests. When the Qing became ever more possessed by the idea that Catholics belonged to a "heretical" organization (as contrasted with the "orthodoxy" of Confucianism) which might threaten the empire's order and rule, district magistrates found it convenient to manipulate non-Catholic communities against the Catholics, leading to discrimination as well as social and political pressure against Catholic families. As a consequence, significant numbers of Catholics withdrew into the remote mountains and hinterlands of western Sichuan, becoming "hidden Christians" whom were mistaken for Buddhists by European missionaries after the lifting of missionary controls in 1858.[3]

Nevertheless, by 1870, the Sichuanese Church had 80,000 baptized members, which was the largest number of Catholics in the entire country. By 1911, the number increased to 118,724 members.[4] Throughout its ecclesiastical history, Sichuan was one of the hotbeds of anti-missionary riots in China.[5]

The primate of the province is the Archbishop of Chongqing, with his seat at St. Joseph's Cathedral. The post has been vacant since the last Archbishop Peter Luo Beizhan died in 2001.[6]

While works on the Catholic missions in the capitals of the Chinese empires are abundant (Chang'an, Khanbaliq/Karakorum, Nanjing, Beijing), few Catholic phenomena have been analysed in the Sichuan Province.[3]

History

Early period

In 1640, Lodovico Buglio, an Italian Jesuit, arrived in Chengdu (Chengtu), the provincial capital, at the invitation of Liu Yuliang, a Sichuanese native from Mianzhu and Grand Secretary of the Ming dynasty. Thirty people received baptism the following year, who were the first Catholics in Sichuan. There was a certain Peter (Petrus) among them, according to An Account of the Entry of the Catholic Religion into Sichuan, he was a descendant of the Prince Xian of Shu,[7] and quite active in the congregation.[8] After the Portuguese Jesuit Gabriel de Magalhães joined the mission in August 1642, work began at once in Chengdu, Baoning and Chongqing.[9]

After the massacre of Sichuan (1644–1646) by Zhang Xianzhong, and consequently, the immigration movement known as "repopulation of Sichuan", a search for surviving converts was carried out during the 1660s by Basil Xu, the then intendant of Eastern Sichuan Circuit, and his mother Candida Xu, both Catholics. They found a considerable number of converts in Baoning, Candida then invited a French Jesuit priest Claude Motel (a.k.a. Claude Métel or Claudius Motel, 1618–1671[10][11]) to serve the congregation. Several churches were built in Chengdu, Baoning and Chongqing under Motel's supervision, and he baptized 600 people in one year.[12]

18th century

The Apostolic Vicariate of Szechwan was established on 15 October 1696, with its headquarters in Chengdu. Its first apostolic vicar was Artus de Lionne, a French missionary of the Paris Foreign Missions Society (Missions étrangères de Paris, abbreviated MEP).[13] De Lionne managed to recruit four priests for his vicariate. In 1700, he entrusted the city of Chengdu and the western part of Sichuan to the MEP priests Jean Basset and Jean-François Martin de La Baluère. Two Lazarists were also placed at his disposal, Luigi Antonio Appiani, an Italian, and Johannes Müllener, a German. De Lionne entrusted them with Chongqing and the eastern part of Sichuan. Two different missionary congregations thus found themselves assuming responsibilities in the same province. Though very few in number and facing considerable hardship, the priests of these two societies competed for territory.[14]

The Lyonese Jean Basset wrote a long memoir in 1702 in Chengdu under the title of Avis sur la Mission de Chine, lamenting the sad state of the Church in Sichuan after so many past efforts. For Basset, there was only one remedy: translating the Bible and authorizing a liturgy in Chinese. "It was", he pointed out, "the practice of the apostles and it is the only way to familiarize the Chinese people with the Christian message".[14] Basset set to work on the translation with the assistance of a local convert, Johan Su. Together they produced a New Testament translation in six large volumes which is now known as the Basset–Su Chinese New Testament.[15][16]

In 1723, the arrival of the Los in Jiangjin made the town an important Catholic center in eastern Sichuan. The Lo family built a church and a clergy house with donations from the local faithful. During a period of ten years from 1736 to 1746, Giovanni Battista Kou (Joannes-Baptista Kou; 1701–1763) had resided in the clergy house while doing missionary work.[17] Kou was a Beijingese trained at the Collegio dei Cinesi in Naples.[18] The faithful from surrounding cities used to gather at the Jiangjin church to sing the Mass and receive the sacraments administered by Father Kou. Musical instruments such as sheng and xiao were used during major Catholic feasts.[17]

During this period, an emerging phenomenon of consecrated virgins came into existence in Sichuan. One of the earliest such virgins was Agnes Yang, a woman from the Mingshan District in western Sichuan. Her baptism was confirmed by an MEP missionary Joachim-Enjobert de Martiliat, author of the first detailed Rules for Consecrated Virgins (1744).[19][20] The latter visited Agnes again in 1733 when she was over 50 and found that she had remained faithful and chaste.[21] These unmarried Catholic women served as baptizers and female catechists for the evangelization among women. The role they played was important in the growth of the Church in Sichuan, because of the segregation of the sexes in China.[22] The most committed promoter of this practice was Jean-Martin Moye, provicar in Eastern Szechwan (future Archdiocese of Chongqing) and Kweichow (future Archdiocese of Guiyang) since 1773, who founded the Congregation of the Sisters of Providence in Lorraine before entering the mission field of Sichuan.[14]

In 1753, the MEP took over responsibility for Catholic mission in Sichuan.[23] In 1756, François Pottier, a young priest ordained in Tours just three years ago, arrived in Sichuan, taking charge as provicar of the five or six thousand Catholics dispersed in the province. After three years of pastoral visits, he was arrested and tortured, spent a few months in prison in Chongqing. In 1767 he was appointed Titular Bishop of Agathopolis and Apostolic Vicar of Szechwan. His episcopal consecration on 10 September 1769 took place in Xi'an, the capital of Shaanxi Province, where he had to flee during a persecution. Having sold his house in Chengdu in 1764, Pottier retired with seven students to a cottage in Fenghuangshan (Phoenix Mountain), 7 kilometers west of Chengdu. His poor school reminded him of the stable in Bethlehem, he called it the "Nativity Seminary". In 1770, his school was denounced to the authorities, and the cottage was destroyed. A few years later, Bishop Pottier resumed the work of training future priests by founding in 1780 a seminary at Long-ki in the Sichuan-Yunnan border region. From 1780 to 1814, forty priests left this seminary and moved to Lo-lang-keou in southern Sichuan shortly after its opening.[14]

In 1783, Pottier chose Jean-Didier de Saint-Martin as coadjutor and ordained him bishop at Chengdu on 13 June 1784. Saint-Martin was imprisoned and then expelled from China the following year, but he managed to return to his post in 1792, the year of Pottier's death. He ensured his own succession by taking Louis Gabriel Taurin Dufresse as coadjutor, whom he ordained Bishop of Tabraca in 1800. This new bishop already had twenty years of experience in Sichuan, where he arrived in 1776. His ministry was interrupted by the persecution of 1784. Dufresse was imprisoned, brought to Beijing and then exiled to Portuguese Macau and the Spanish Philippines, he secretly returned to Chengdu in 1789 and was put in charge of the Eastern Szechwan and Guizhou missions. On the death of Saint-Martin in 1801, he took charge of the entire province. Despite the insecurity and multiple setbacks, the Church in Sichuan was then relatively prosperous. In 1756 there were 4,000 Catholics and two local priests in the province. In 1802, the number increased tenfold with 40,000 Catholics and 16 local priests. The pastoral experience accumulated during the eighteenth century made it possible to establish a general directory of the conditions of Christian life and the ministry of the sacraments.[14]

19th century

In 1803, Bishop Dufresse convened the first synod in China near Chongqingzhou (Tchong-king-tcheou, 'Chongqing Prefecture'), 40 kilometers west of Chengdu.[14][24] Thirteen Chinese priests and two French priests participated, namely Dufresse and Jean-Louis Florens.[25] The decisions refer primarily to the pastoral care of the sacraments. Chapter 10 deals with the ministry of the priests, recommending fervor in the spiritual life and discretion in temporal things. The provisions of the Synod of Sichuan were to guide the apostolate in this province until the Plenary Council of Shanghai in 1924.[14][26]

In 1815, Dufresse was arrested and beheaded, along with another bishop and nine priests in Chengdu on 14 September.[27] His head was tied to a post and his body was exposed for three days as a warning to others. He was canonized a saint by Pope John Paul II on 1 October 2000.[28]

Around 1830, the MEP, as a society of apostolic life which had the objective of evangelizing non-Christian Asian countries, opened a college at Muping (in French, Moupin) known as the "Muping Seminary" or Collège de l'Annonciation (presently the Annunciation Church at Dengchigou) to recruit local clergy. Many of its missionaries were well educated in the natural sciences (botany, zoology, geology) and sought to come into contact with scientific establishments of Paris.[29]

Today the Annunciation Church is well-remembered thanks to Armand David, a Lazarist missionary as well as a zoologist and a botanist, the "discoverer" of the pandas, who in 1869 arrived at Muping in a sedan chair. About fifty local students studied at the Muping Seminary under the direction of Anatole Dugrité, superior of the Collège de l'Annonciation. At that time, the college and mission station belonged to the Apostolic Vicariate of Western Szechwan whose bishop was Annet-Théophile Pinchon.[30]

At Bailu, Pengzhou, construction of the Annunciation Seminary was started in 1895 by Bishop Marie-Julien Dunand, successor to Bishop Pinchon who died in 1891.[31] The seminary was designed by two French missionaries, Alexandre Perrodin and Léon Rousseau. The construction lasted 13 years, after its completion in 1908, it became an important institute for the training of priests in the province at that time.[32]

That same year (1895) was marked by a serious outbreak of anti-foreign agitation began in the capital Chengdu, and thence spread throughout the province.[33] In the capital, the property of the Roman Catholics and that of three Protestant missions was destroyed;[34] and all missionaries of all missions, Catholic and Protestant alike, were thankful to escape with their lives.[35]

.jpg.webp)

On 29 July 1896, Fr. Adolphe Roulland was sent to the Apostolic Vicariate of Eastern Szechwan by Paris Foreign Missions Society. The next year, he was appointed vicar at Youyang (Yeou-yang), in the city of Chongqing. Five years later (1902), he was appointed parish priest of Mapaochang (Ma-pao-tchang; now merged with Shima Town) in the same city, where he stayed for seven years.[36] Fr. Roulland was a spiritual brother of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. He gifted the Carmelite Convent of Lisieux the book by Léonide Guiot, La Mission du Su-Tchuen au XVIIIme siècle : Vie et Apostolat de Mgr Pottier, son fondateur ('The Su-Tchuen Mission in the 18th Century: Life and Apostolate of Bishop Pottier, Its Founder', 1892), which had a great influence on Thérèse.[37]

Thérèse gave Roulland a Sacred Heart picture accompanied by a prayer: "O Divine Blood of Jesus! Water our mission, sprout the elect." Surrounded by floral marginalia, the heart with a small cross is depicted dripping a drop of blood on Su-Tchuen oriental, denoting the spilled Divine Blood on the Mission of Chongqing.[38][39]

In her letter to Roulland dated 30 July 1896, Thérèse expressed her hope for a visit to Sichuan: "I have attached the map of Su-Tchuen on the wall where I work, [...] I will ask Jesus' permission to go to visit you at Su-Tchuen, and we shall continue our apostolate together."[40] Today, in addition to keeping one of Thérèse's letters to Fr. Roulland, the Church of Janua Coeli at Shima (重慶石馬眞原堂) also preserves one of her relics.[41]

20th century

In 1905, four French missionaries were killed in the Bathang uprising, including Jean-André Soulié, who worked in the Apostolic Vicariate of Tibet. He was captured, tortured and shot by lamas close to Yaregong.[42] Nine years later (1914), Jean-Théodore Monbeig, another French missionary working in the Sichuan-Tibetan border region, was killed by lamas near Lithang, not long after helping revive the Christian community at Bathang.[43][44]

In 1918, French missionary François-Marie-Joseph Gourdon edited and published in Chongqing An Account of the Entry of the Catholic Religion into Sichuan, by the authority of Célestin Chouvellon, Bishop of Eastern Szechwan. This work is allegedly based on Gabriel de Magalhães's Relação das tyranias obradas por Canghien Chungo famoso ladrão da China em o anno de 1651.[45] In addition, An Account of the Entry of the Catholic Religion into Anyue, detailing the history of the Church in Anyue County, was published in 1924, with the approval of Urbain Claval, Provicar of Eastern Szechwan.[46]

By the end of 1921, there were 143,747 Catholic Christians in Sichuan. These worshipped in 826 chapels and churches scattered throughout the province which was divided into four bishoprics with episcopal residences at Chengdu, Chongqing, Suifu and Ningyuan. Almost 8,000 adults were baptized into the Roman Catholic Church during 1918. In addition to regular evangelistic activities, the Church maintained nearly 400 parish schools of primary grade with over 7,500 students. There were three colleges in the province, two in Chongqing and one in Chengdu; ten seminaries, and five schools for girls. Roman Catholic missions also reported five hospitals and seven dispensaries.[47]

In February 1928, Segundo Miguel Rodríguez, José Morán Pan and Segundo Velasco Arina sailed for China. Initially, they were put in charge of the seminary of the Congregation of the Disciples of the Lord in the Apostolic Vicariate of Süanhwafu, Hebei Province. Subsequently, they were transferred to Sichuan as the first band of Spanish Redemptorist missionaries to take up work in that province.[48] Their first permanent foundation was made in Chengdu on 24 April 1934,[49] which expanded to include a mission house and a chapel.[50] In addition to the Apostolic Vicariate of Chengtu, the Apostolic Vicariate of Ningyuanfu became their second mission base in 1938. This district covers the entire Nosu Country that is further to the west and bordered by eastern Tibet.[51] The last Spanish Redemptorists were expelled from China by the communist regime in 1952.[48]

In 1930, a Spanish Franciscan friar and artist Pascual Nadal Oltra arrived in Moxi (Mosimien), a small town located in Garzê, one of the three Tibetan regions of Western Sichuan. With the support of the Bishop of Tatsienlu (Pierre-Philippe Giraudeau) and his coadjutor Pierre Valentin, Oltra, the Father Guardian Plácido Albiero, a Canadian friar Bernabé Lafond and an Italian José Andreatta formed the founding community of a leper colony established near St. Anne's Church,[52] known as St. Joseph's Home.[53] There were dormitories for leper patients, a pharmacy and an infirmary. The installation of the first lepers was not easy, given their ignorance and the situation of marginalization and social aversion in which they lived. Nevertheless, by 1935, the missionaries already had a hundred patients.[54]

In May 1935, a communist army column led by Mao Zedong (Mao Tse Tung) was fleeing Chiang Kai-shek's regular army to northwest China through the Moxi area, part of a military retreat later known as Long March. According to the Valencian Franciscan friar José Miguel Barrachina Lapiedra, author of the book Fray Pascual Nadal y Oltra: Apóstol de los leprosos, mártir de China, and a report published in Malaya Catholic Leader, the official newspaper of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Singapore: "The communist soldiers entered the leper colony, they looted the residence and arrested the friars and sisters. Many of the lepers tried to defend the missionaries, but they were shot by the soldiers. The Franciscans were then brought before Mao Tse Tung, who interrogated them, imprisoned two of them, Pascual Nadal Oltra and an Italian friar Epifanio Pegoraro, and released the rest. There were more than 30,000 Reds in the band, including a large number of women. Before their departure, the soldiers ransacked the village, carrying away everything movable and edible, left the people of the district without means of subsistence. Days later, on 4 December 1935, the army reached Leang Ho Kow, Tsanlha, where the two Franciscans were beheaded with a sword."[55][56][57]

In her letter to the poet Raymond Cortat, dated 17 January 1937, Marie-Rosine Sahler, a member of the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary, recounts in detail her journey, her arrival in China and her life in the Mosimien leper colony, a testimony about the political hardship: "In 1935, the leper colony was savagely attacked by communist army and the mission community had to flee to the mountains and stay there for eight days. Upon her return, she found the leper colony ransacked and all supplies looted. Nevertheless, the community managed to recover and welcome back the sick, who in 1937 were 148 people."[58]

In 1947, Trappist monks from Our Lady of Joy Abbey (Diocese of Zhengding) transferred their monastery to Xindu County, Chengdu, due to the ongoing civil war. Father Paulin Li and forty monks reached their destination via Shanghai. They remained in Sichuan for two years, until the end of 1949, when the communist invasion reached there, too. By which time, north and central China were already taken over by communists. It became evident that the monastic community had to move again.[59][60] On Christmas Day, 1949, communists occupied the Chengdu Monastery and its surrounding land. A couple of the young monks were severely beaten, three were martyred after brutal torture, namely, Vincent Shi, Albert Wei, and Father You.[61] Father Paulin Li managed to transfer ten of the monks to Canada, including nine Chinese nationals and one Belgian. Eventually, the abbey was re-established on Lantau Island, British Hong Kong. A permanent location for Our Lady of Joy Abbey at Hong Kong was secured on 19 February 1956.[60]

Current situation

After the communist takeover of China in 1949, Catholicism in China, like all religions, has since been permitted to operate only under the supervision of the State Administration for Religious Affairs. All legal worship has to be conducted in government-approved churches belonging to the Catholic Patriotic Association, which does not accept the primacy of the Roman pontiff.[64] Some missionaries were arrested and sent to "thought reform centers" in which they underwent disturbing re-education process in a vindictive prison setting.[65]

During the Land Reform Movement in the early 1950s, several Legion of Mary (LOM) organizations in Pengzhou were banned and persecuted, since the communist regime termed the LOM a "counter-revolutionary force".[66][67]

In 1989, while an administrator of the Diocese of Qinzhou, John Baptist Wang Ruohan was consecrated "underground bishop" of Kangding by Paul Li Zhenrong, Bishop of Xianxian.[68] In 2011, John Baptist was arrested by Chinese security forces, along with his brothers, Bishop Casimir Wang Mi-lu and Father John Wang Ruowang, as well as a group of lay faithful, who do not belong to the government-authorized Catholic Patriotic Association.[69]

In 2005, Chinese government officials planned to consecrate two bishops in the Dioceses of Chengdu and Leshan (Jiading) without papal mandate, whose appointments were rejected by the approximately 140,000 faithful in both dioceses, due to their open political maneuvering.[70]

Following the devastation of dozens of churches by the 2008 Sichuan earthquake,[71] Audrey Donnithorne set up a fund for the reconstruction of churches, schools and nurseries in that province where she had been born in 1922. Audrey was the daughter of Vyvyan Donnithorne, an English Anglican missionary stationed at the Gospel Church of Hanchow in northern Sichuan during the 1930s. She converted to Roman Catholicism in 1943,[72] and received baptism at Immaculate Conception Cathedral, Chengdu.[73] She was crucial in the reconciliation of a "patriotic" bishop in Sichuan with the Holy See, leading to the establishment of unity between the "underground" and "patriotic" churches in that province. She was expelled from Mainland China in 1997 due to her activities for the Church.[74]

In 2011, after trying to reclaim two former church properties in Moxi that were confiscated by authorities in the 1950s, Sister Xie Yuming and Father Huang Yusong were attacked by a group of unknown assailants on 3 September. The nun was severely beaten while the priest suffered minor injuries. The properties, a Latin school demolished by the authorities, and a boys' school occupied by Moxi government officials by the time, were formerly owned by the Diocese of Kangding.[75]

On 29 June 2022, a celebration of the anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party was held at the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Leshan (Diocese of Jiading), for political reasons. The Catholics were called to "listen to the word of the Party, feel the grace of the Party, and follow the Party". According to a Catholic source contacted by AsiaNews, "in China it is no longer a question of listening to the Lord, of feeling his grace and following him. This is the root of the disease of the Chinese Church today, it is difficult to get away from the influence of ideology. Politics has entered the Church", and persecution of Church members who do not want to submit to religious bodies controlled by the Party continues.[76]

Dioceses

The Apostolic Vicariate of Szechwan was established in 1696 with its seat in Chengdu. In 1856, the Apostolic Vicariate of Szechwan was renamed the Apostolic Vicariate of Northwestern Szechwan (also known as Apostolic Vicariate of Western Szechwan) upon the establishment of the Apostolic Vicariate of Southeastern Szechwan,[77] with the seat of the latter in Chongqing.[78][79]

In 1860, the Apostolic Vicariate of Southern Szechwan was established with its seat in Suifu.[80] In 1910, the Apostolic Vicariate of Kienchang was established with its seat in Ningyüanfu.[81] In 1924, the Apostolic Vicariate of Northwestern Szechwan was renamed the Apostolic Vicariate of Chengtu, which was eventually promoted to Diocese of Chengtu in 1946.[78]

Today, the Catholic Church in Sichuan has 1 archdiocese and 7 dioceses covering the entire province and the city of Chongqing.

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chongqing (Chungking / Tchong-kin-fou; Archidioecesis Ciomchimensis): Established on 2 April 1856 as Apostolic Vicariate of Southeastern Szechwan, renamed on 24 January 1860 as Apostolic Vicariate of Eastern Szechwan, renamed on 3 December 1924 as Apostolic Vicariate of Chungking, promoted on 11 April 1946 as Metropolitan Archdiocese of Chungking.[77][82] Its diocesan seat is the Cathedral of St. Joseph, Chongqing.[83]

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Chengdu (Chengtu / Tchen-tou-fou; Dioecesis Cemtuana): Established on 15 October 1696 as Apostolic Vicariate of Szechwan, renamed on 2 April 1856 as Apostolic Vicariate of Northwestern Szechwan (a.k.a. Apostolic Vicariate of Western Szechwan), renamed on 3 December 1924 as Apostolic Vicariate of Chengtu, promoted on 11 April 1946 as Diocese of Chengtu.[84][78] Its diocesan seat is the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Chengdu.[85]

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Jiading (Kiating / Kia-tin; Dioecesis Chiatimensis): Established on 10 July 1929 as Apostolic Prefecture of Yachow (today known as Ya'an), promoted on 3 March 1933 as Apostolic Vicariate of Yachow, renamed on 9 February 1938 as Apostolic Vicariate of Kiating, promoted on 11 April 1946 as Diocese of Kiating (today known as Leshan).[86][87] Its diocesan seat is the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Leshan.[88]

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Kangding (Kangting / Tatsienlu / Ta-tsien-lou; Dioecesis Camtimensis): Established on 27 March 1846 as Apostolic Vicariate of Lhassa (Lhasa), renamed on 28 July 1868 as Apostolic Vicariate of Thibet (Tibet), renamed on 3 December 1924 as Apostolic Vicariate of Tatsienlu (today known as Kangding, in Sichuanese Tibet), promoted on 11 April 1946 as Diocese of Kangting.[89][90] Its diocesan seat is the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart, Kangding.[91]

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Ningyuan (Ningyüanfu / Lin-yuen-fou; Dioecesis Nimiuenensis): Established on 12 August 1910 as Apostolic Vicariate of Kienchang (today known as Xichang, in Nosuland), renamed on 3 December 1924 as Apostolic Vicariate of Ningyüanfu, promoted on 11 April 1946 as Diocese of Ningyüan.[92][93] Its diocesan seat is the Cathedral of the Angels, Xichang.[94]

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Shunqing (Shunking / Choen-kin-fou; Dioecesis Scioenchimensis): Established on 2 August 1929 as Apostolic Vicariate of Shunking (today known as Nanchong), promoted on 11 April 1946 as Diocese of Shunking.[95][96] Its diocesan seat is the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Nanchong.[97]

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Suifu (Suifou / Souifou / Su-tcheou-fou; Dioecesis Siufuana): Established on 24 January 1860 as Apostolic Vicariate of Southern Szechwan, renamed on 3 December 1924 as Apostolic Vicariate of Suifu (today known as Yibin), promoted on 11 April 1946 as Diocese of Suifu.[98][99] Its diocesan seat is the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, Yibin.[100]

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Wanxian (Wanhsien / Ouan-hien; Dioecesis Uanscienensis): Established on 2 August 1929 as Apostolic Vicariate of Wanhsien (today known as Wanzhou), promoted on 11 April 1946 as Diocese of Wanhsien.[101][102] Its diocesan seat is the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Wanzhou.[103]

St. Thérèse of Lisieux Church, Chongqing (Archdiocese of Chongqing)

St. Thérèse of Lisieux Church, Chongqing (Archdiocese of Chongqing) Our Lady of Lourdes Church, Mianyang (Diocese of Chengdu)

Our Lady of Lourdes Church, Mianyang (Diocese of Chengdu) Interior of Our Lady of Lourdes Church at Mianyang

Interior of Our Lady of Lourdes Church at Mianyang Cathedral of the Angels, Xichang (Diocese of Ningyuan)

Cathedral of the Angels, Xichang (Diocese of Ningyuan)![Annunciation Church, Dengchigou [fr] (Diocese of Jiading)](../I/Mission_catholique_et_%C3%A9glise_de_Dengchigou_(Baoxing%252C_Sichuan%252C_Chine)_-_www.panda.fr.jpg.webp) Annunciation Church, Dengchigou (Diocese of Jiading)

Annunciation Church, Dengchigou (Diocese of Jiading)_-_www.panda.fr.jpg.webp) Interior of the Annunciation Church at Dengchigou

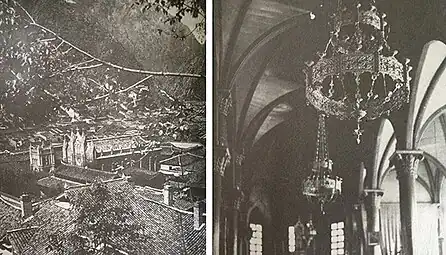

Interior of the Annunciation Church at Dengchigou Exterior and interior of the former Sacred Heart Cathedral at Kangding (Diocese of Kangding)

Exterior and interior of the former Sacred Heart Cathedral at Kangding (Diocese of Kangding) Our Lady of the Sacred Heart Church, Yerkalo (Diocese of Kangding)[104]

Our Lady of the Sacred Heart Church, Yerkalo (Diocese of Kangding)[104]![Sacred Heart Church, Cizhong [fr] (Diocese of Kangding)](../I/Catholic_Church_Cizhong_Yunnan_China.jpg.webp) Sacred Heart Church, Cizhong (Diocese of Kangding)[note 1]

Sacred Heart Church, Cizhong (Diocese of Kangding)[note 1]![Altar of St. Anne's Church, Moxi [es] (Diocese of Kangding)](../I/St._Anne's_Church%252C_Mosimien_(interior)_2.jpg.webp) Altar of St. Anne's Church, Moxi (Diocese of Kangding)

Altar of St. Anne's Church, Moxi (Diocese of Kangding) Altar of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception at Chengdu (Diocese of Chengdu)

Altar of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception at Chengdu (Diocese of Chengdu) Diocesan curia of Bishop of Chengdu

Diocesan curia of Bishop of Chengdu

See also

- Christianity in Sichuan

- Catholic Church in Mianyang

- Catholic Church in Tibet

- Catholic missions

- Anglican Diocese of Szechwan

- Anti-Christian Movement (China)

- Antireligious campaigns of the Chinese Communist Party

- Chinese Rites controversy

- Youyang anti-missionary riot

- Paul Liu Hanzuo – 19th-century martyr saint from Lezhi County

- Saint Lucy Yi Zhenmei – 19th-century virgin martyr from Mianyang, canonized on 1 October 2000 by Pope John Paul II

- Maurice Tornay – Swiss missionary ministering in the Diocese of Kangding

- Francis Xavier Ford – American Catholic missionary in China, tortured by Chinese communists and died in prison

- Catholic Church in Shaanxi – neighbouring province

- Category:Sichuanese Roman Catholics

- Category:Roman Catholic churches in Chongqing

- Category:Roman Catholic churches in Sichuan

- Category:Roman Catholic churches in Tibet

- Category:Roman Catholic missionaries in Sichuan

- Category:Roman Catholic missionaries in Tibet

Notes

- ↑ The Cizhong Catholic Church at Deqin falls under the administration of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Dali, although it was formerly part of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Kangding; and from the Vatican's perspective, the church still belongs to the Diocese of Kangding.[104]

References

- ↑ D'Elia, Pasquale (15 December 1946). "De sinensis expeditionis transitu in ecclesiam hierarchicam". Periodica de Re Morali Canonica, Liturgica (in Latin). 35 (3–4): 266. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ↑ Gourdon 1981, p. 6.

- 1 2 Laamann, Lars Peter. "Catholic Communities in Qing and Republican China: The Teaching of Heaven in the Land of the Four Rivers". sichuanreligions.com. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ↑ Lü 1976, p. 266.

- ↑ Lü 1976, p. 282.

- ↑ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Chongqing". gcatholic.org. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ Chengdu Local Records Compilation Committee, ed. (1998). "天主教——第一节:传入" [Chapter I: The Entry of Catholicism]. 成都市志‧宗教志 [Annals of Chengdu City: Religion] (in Simplified Chinese). Chengdu: Sichuan Lexicographical Press. p. 176. ISBN 9787805437316.

- ↑ Gourdon 1981, p. 4.

- ↑ Gourdon 1981, p. 5.

- ↑ Charbonnier, Jean-Pierre (2007). "10. Candida Xu: A Mother of the Church — Apostolic Journeys". Christians in China: A.D. 600 to 2000. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. ISBN 978-0-89870-916-2.

- ↑ Dehergne, Joseph (15 January 2019). "法國耶穌會士前往中國內地傳教" [French Jesuit missionaries in China]. macaumemory.mo (in Traditional Chinese). Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ↑ Gourdon 1981, pp. 63–65.

- ↑ Guiot 1892, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Charbonnier, Jean. "Partir en mission 'à la Chine'". mepasie.org (in French). Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ Song, Gang (10 March 2021). "The Basset-Su Chinese new Testament". In Yeo, K. K. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Bible in China. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 79–94. ISBN 9780190909796.

- ↑ Song, Gang (2017). "A Minor Figure, A Large History: A Study of Johan Su, a Sichuan Catholic Convert in the Early Qing Dynasty". hub.hku.hk. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- 1 2 Gourdon 1981, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Zheng, Yangwen (2017). Sinicizing Christianity. "Studies in Christian Mission" series (vol. 49). Leiden: Brill Publishers. p. 37. ISBN 9789004330382.

- ↑ Tiedemann, R. G. (2018). "Chinese Female Propagators of the Faith in Modern China: The Tortuous Transition from the 'Institute of Virgins' to Diocesan Religious Congregations" (PDF). Religions & Christianity in Today's China. VIII (2): 56. ISSN 2192-9289. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ De Martiliat, Joachim-Enjobert (1921). "守貞修規明述" [An Introduction to the Rules]. 童貞修規 [Rules for Consecrated Virgins] (in Traditional Chinese). Chongqing: Sheng Chia Book-Printing Bureau. pp. 1–4.

- ↑ Li, Ji, ed. (18 November 2021). Missions Étrangères de Paris (MEP) and China from the Seventeenth Century to the Present. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-90-04-47210-5.

- ↑ Mungello, D. E. (29 March 2021). "Christian Virgins (Chaste Women) in Sichuan". This Suffering Is My Joy: The Underground Church in Eighteenth-Century China. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 120. ISBN 9781538150306.

- ↑ Ma, Te (8 November 2018). "On the Trail of Sichuan's Catholic Past". u.osu.edu. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ Wright, Arnold, ed. (1908). "Chapter: The Roman Catholic Church". Twentieth Century Impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and other Treaty Ports of China: Their History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources. London: Lloyd's Greater Britain publishing Company. p. 322.

- ↑ Camps, Arnulf (2009). "Catholic Missionaries (1800–1860)". In Tiedemann, R. G. (ed.). Handbook of Christianity in China, Volume Two: 1800–present. Leiden: Brill Publishers. p. 115. ISBN 978-90-04-19018-4.

- ↑ Synodus Vicariatus Sutchuensis habita in districtu civitatis Tcong King Tcheou; Anno 1803, Diebus secunda, quinta, et nona Septembris [The Synod of the Vicariate of Szechwan held in the District of the City of Chung King Chow, in the Year 1803, on the Second, Fifth, and Ninth Days of September] (in Latin). Rome: Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide. 1822. hdl:2027/coo.31924023069010.

- ↑ "Canonisation de martyrs de l'église en Chine". missionsetrangeres.com (in French). 18 March 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ "Saint Jean-Gabriel-Taurin Dufresse". catholicsaints.info. 8 February 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ Van Grasdorff, Gilles (2007). La belle histoire des Missions étrangères 1658–2008 (in French). Paris: Éditions Perrin. ISBN 9782262025663.

- ↑ Pouille, Jérôme (1 March 2019). "Il y a 150 ans, le Père Armand David arrivait dans la principauté de Moupin, l'actuel comté de Baoxing". panda.fr (in French). Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ Liao, Yiwu (2014). "De nieuwe bekeerde". God is rood: Het geheime verhaal over het voortbestaan en de bloei van het christendom in communistisch China (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Atlas Contact. ISBN 9789045023441.

- ↑ Tan, Tieniu; Ruan, Qiuqi; Chen, Xilin; Ma, Huimin; Wang, Liang, eds. (2013). Advances in Image and Graphics Technologies: Chinese Conference, IGTA 2013, Beijing, China, April 2-3, 2013, Proceedings. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 120–121. ISBN 9783642371493.

- ↑ Missionary Cameralogs: West China. New York: American Baptist Foreign Mission Society. 1920. p. 20.

- ↑ Stewart, Emily Lily (1934). "Chapter II. The Way Reviewed". Forward in Western China. London: Church Missionary Society.

- ↑ Various authors (1920). Our West China Mission: Being a Somewhat Extensive Summary by the Missionaries on the Field of Work during the First Twenty-five Years of the Canadian Methodist Mission in the Province of Szechwan, Western China. Toronto: Missionary Society of the Methodist Church. p. 42.

- ↑ "Adolphe ROULLAND". irfa.paris (in French). Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ↑ Marin, Catherine (2 November 2010). "L'union apostolique de Thérèse de l'Enfant-Jésus et d'Adolphe Roulland, missionnaire en Chine (1896-1897)". Thérèse de Lisieux et les missions. "Histoire et missions chrétiennes (Histoire, monde et cultures religieuses)" series (No. 15) (in French). Paris: Éditions Karthala. ISBN 9782811104238.

- ↑ Zuazua, Dámaso (May 2014). "Santa Teresita del Niño Jesús de actualidad en China". La Obra Máxima (in Spanish). San Sebastián: La Obra Máxima Revista Carmelitana y ONGD para el Desarrollo. p. 22. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ↑ "Rediscovery of an image of Thérèse after 80 years in a cupboard". archives.carmeldelisieux.fr. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ↑ Therese of Lisieux (29 September 2014). Letters of St. Therese of Lisieux, Volume II: General Correspondence 1890-1897. Translated by Clarke, John. Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications. ISBN 9781939272287.

- ↑ "各地善度圣女小德肋撒主保、开启传教月迎接传教节" [Celebration of the Feast Day of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux and the Missionary Month took place in various places in China]. fides.org (in Simplified Chinese). 8 October 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ↑ Launay, Adrien (1905). "Un Missionnaire Massacré au Thibet : M. Soulié". archives.mepasie.org (in French). Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ "Jean-Théodore MONBEIG". irfa.paris (in French). Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ "Monbeig, Jean-Théodore (1875-1914)". plants.jstor.org. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ Chan, Hok-lam (2011). "傳教士對張獻忠據蜀稱王的記載:《聖教入川記》的宗教與文化觀點" [Jesuits' Impressions on Zhang Xianzhong in Sichuan (1644–1647) from Buglio, Magalhães, and Gourdon: Contrasting Religious and Cultural Perspectives of Shengjiao Ru Chuan Ji] (PDF). 中國文化研究所學報 [Journal of Chinese Studies] (in Traditional Chinese). Hong Kong: Institute of Chinese Studies (52): 68. ISSN 1016-4464. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ Qin & Shen 2008, p. 111.

- ↑ Stauffer, Milton T., ed. (1922). The Christian Occupation of China. Shanghai: China Continuation Committee. p. 228.

- 1 2 Tiedemann, R. G. (1 July 2016). Reference Guide to Christian Missionary Societies in China: From the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century. Milton Park: Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 9781315497310.

- ↑ Boland, S. J. (1987). A Dictionary of the Redemptorists (PDF). Rome: Collegium S. Alfonsi de Urbe. p. 76. OCLC 35115469.

- ↑ Donnithorne, Audrey G. (29 March 2019). China: In Life's Foreground. North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing. ISBN 9781925801576.

- ↑ Boland, Samuel J. (2002). "The Redemptorists and the China Mission" (PDF). Spicilegium Historicum Congregationis SSmi Redemptoris (50): 606. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ↑ Barrachina Lapiedra 1990, p. 59.

- ↑ "Leprosy Institutions in China" (PDF). International Journal of Leprosy. 17: 469. 1949. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ Barrachina Lapiedra 1990, p. 65.

- ↑ Garcia, Sara (29 November 2006). "Investigació a fons de la mort de Fra Pascual Nadal Oltra". radiopego.com (in Valencian). Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ↑ "Investigan la muerte en 1935 de un fraile de Pego en China". lasprovincias.es (in Spanish). 29 November 2006. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ "Abducted Franciscans Still Missing: Leper Asylum Near Tibetan Border Invaded by Reds". Malaya Catholic Leader. Vol. 1, no. 35. Singapore. 31 August 1935. p. 7. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ Moulier, Pascale (2020). "Une missionnaire aurillacoise au Tibet". diocese15.fr (in French). Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ Ferreux, Octave (20 December 2022). "The Monastery of Our Lady of Joy (Zhengding) Evacuated". History of the Congregation of the Mission in China. Hyde Park, NY: New City Press. ISBN 9781565485464.

- 1 2 "聖母神樂院滄桑五十年簡史——乙、四川成都的【神樂院】(一九四七 ~ 一九五零)" [A brief history of the 50-year vicissitudes of Our Lady of Joy Abbey: The Chengdu Monastery, Sichuan (1947–1950)]. catholic.org.tw (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 3 December 2005. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ↑ Hattaway, Paul (2007). "Christian Martyrs in Sichuan: Vincent Shi, Albert Wei, & Father You". China's Book of Martyrs (Fire & Blood). Manchester: Piquant Editions. ISBN 9781903689400.

- ↑ "Christians in China Stats: Sichuan". asiaharvest.org. 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ↑ "Christians in China Stats: Chongqing". asiaharvest.org. 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ↑ Moody, Peter R. (2013). "The Catholic Church in China Today: The Limitations of Autonomy and Enculturation". Journal of Church and State. 55 (3): 403–431. doi:10.1093/jcs/css049. JSTOR 23922765. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ Lifton, Robert J. (1957). "Chinese Communist 'Thought Reform': Confession and Re-Education of Western Civilians". Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 33 (9): 626–644. PMC 1806208. PMID 19312633.

- ↑ Qin & Shen 2008, p. 225.

- ↑ Rozario, Rock Ronald (17 January 2022). "Winter Olympics venue tainted by China's massacre of Catholics". ucanews.com. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ↑ Brender, Andreas (2012). "Bishops in China, W: Wang Ruohan, John Baptist". bishops-in-china.com. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ↑ Wang, Zhicheng (24 August 2011). "Tianshui: police arrest dozens of underground priests and lay faithful". asianews.it. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ↑ "Catholic World News: PRC Government to Force New Bishops on Registered Catholic Church in Sichuan". cecc.gov. 21 March 2005. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ↑ "Dozens of churches destroyed or devastated by Sichuan earthquake". asianews.it. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ↑ Zhang, Emma (10 January 2021). "Book Review: China: In Life's Foreground". hkrbooks.com. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ↑ Wang, Teresa (10 June 2020). "四川:天主教南充教区为董育德教授举行隆重追思弥撒" [Sichuan: Solemn Memorial Mass for Professor Audrey Donnithorne Held in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Nanchong]. Faith Weekly (in Simplified Chinese). Shijiazhuang. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ↑ Cairns, Madoc (26 June 2020). "Obituary: Audrey Donnithorne". The Tablet. London. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ↑ "Nun, priest beaten by mob". ucanews.com. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ "Bishop Lei celebrates the birth of China's Communist Party in Leshan cathedral". asianews.it. 2 July 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- 1 2 "Archdiocese of Chongqing [Chungking]". catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Diocese of Chengdu". ucanews.com. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ Planchet 1917, p. 211.

- ↑ Planchet 1917, p. 215.

- ↑ Planchet 1917, p. 219.

- ↑ "Archdiocese of Chongqing". ucanews.com. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Cathedral of St. Joseph, Chongqing". gcatholic.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Chengdu [Chengtu]". catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception (Pinganqiao Church), Chengdu". gcatholic.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Leshan [Kiating]". catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Leshan". ucanews.com. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Cathedral of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Leshan". gcatholic.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Kangding [Kangting]". catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Kangding". ucanews.com. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Cathedral of the Sacred Heart, Kangding". gcatholic.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Xichang [Ningyüan]". catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Xichang". ucanews.com. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Cathedral of the Angels, Xichang". gcatholic.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Nanchong [Shunking]". catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Nanchong". ucanews.com. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Cathedral of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Nanchong". gcatholic.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Yibin [Suifu]". catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Yibin". ucanews.com. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, Yibin". gcatholic.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Wanxian [Wanhsien]". catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Diocese of Wanxian". ucanews.com. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Wanzhou". gcatholic.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- 1 2 Lim, Francis Khek Gee, ed. (7 May 2013). Christianity in Contemporary China: Socio-cultural Perspectives. "Routledge Studies in Asian Religion and Philosophy" series. Milton Park: Routledge. pp. 111–112. ISBN 9781136204999.

The Alulhaka chapel was part of a network of fourteen chapels located in the remote hills around Gongshan county town, where the main Catholic church of the county was located. This network of chapels and churches, together with those in the neighbouring counties in northern Yunnan, are in turn part of the Dali diocese. At least this is how the official China Catholic Patriotic Church currently draws the boundary of the diocese. From the Vatican's perspective, the churches in Gongshan, Deqin and neighbouring counties in Yunnan, Yanjing in Tibet, and Bathang, Lithang, and Kangding in Sichuan, still belong to the Diocese of Kangding that was established in 1946.

Bibliography

- Barrachina Lapiedra, José M. (1990). Fray Pascual Nadal y Oltra: Apóstol de los leprosos, mártir de China (in Spanish). Valencia: Unión Misional Franciscana. ISBN 84-404-8209-4.

- Gourdon, François-Marie-Joseph, ed. (1981) [1918]. 圣教入川记 [An Account of the Entry of the Catholic Religion into Sichuan] (in Simplified Chinese). Chengdu: Sichuan People's Publishing House.

- Guiot, Léonide (1892). La Mission du Su-Tchuen au XVIIIᵐᵉ siècle : Vie et Apostolat de Mgr Pottier, son fondateur (PDF) (in French). Paris: Téqui Libraire-Éditeur.

- Lü, Shih-chiang (1976). "晚淸時期基督敎在四川省的傳敎活動及川人的反應(1860–1911)" [The Evangelization of Sichuan Province in the Late Qing Period and the Responses of the Sichuanese People (1860–1911)]. History Journal of the National Taiwan Normal University (in Traditional Chinese). Taipei: National Taiwan Normal University Department of History.

- Planchet, J.-M. (1917). Les Missions de Chine et du Japon (PDF) (in French). Peking: Imprimerie des Lazaristes.

- Qin, Heping; Shen, Xiaohu, eds. (2008). 四川基督教资料辑要 [A Collection of Historical Documents on Christianity in Sichuan] (in Simplified Chinese). Chengdu: Bashu Publishing House. ISBN 978-7-80752-226-3.

External links

- "Catholic Smalltown Life in Qing Sichuan", Sichuan Religions Online Lecture Series No. 6 — Prof. Lars Peter Laamann 19 March 2022 on YouTube

- Longue piste dans l'Himalaya (documentary about four scouts helping with the development of the local Catholic Church in Yunnanese Tibet, part of the Diocese of Kangding) on YouTube (in French)

.jpg.webp)