Conservative Party of Canada Parti conservateur du Canada | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | July 1, 1867 |

| Dissolved | December 10, 1942 |

| Merger of | Parti bleu |

| Succeeded by | Progressive Conservative Party of Canada |

| Ideology | Conservatism[1] Expansionism[1][2] Protectionism[3] Imperialism[4] |

| Colours | Blue |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Canada |

|---|

|

The Conservative Party of Canada has gone by a variety of names over the years since Canadian Confederation. Initially known as the "Liberal-Conservative Party", it dropped "Liberal" from its name in 1873, although many of its candidates continued to use this name.

As a result of World War I and the Conscription Crisis of 1917, the party joined with pro-conscription Liberals to become the "Unionist Party", led by Robert Borden from 1917 to 1920, and then the "National Liberal and Conservative Party" until 1922. It then reverted to "Liberal-Conservative Party"[5] until 1938, when it became simply the "National Conservative Party".[6] It ran in the 1940 election as "National Government" even though it was in opposition.

The party was almost always referred to as simply the "Conservative Party" and, less formally, "Tories".

In 1942, the Conservatives attempted to broaden their base by electing Manitoba Progressive Premier John Bracken as their new leader at the 1942 leadership convention. Bracken agreed to become the party's leader on the condition that it change its name to the "Progressive Conservative Party of Canada".

Origins

Liberal-Conservative Party

The roots of the party are in the pre-Confederation Province of Canada. In 1853, the bleus from Canada East and the Tories and moderate reformers from Canada East joined together in a coalition government under the dual premiership of Allan MacNab and A.-N. Morin. It was out of this coalition that the Liberal-Conservative Party was formed.

Confederation

Macdonald became the leader of the Conservative Party and formed the first national government in 1867. The party brought together ultramontane Quebec Catholics, pro-tariff businessmen, United Empire Loyalists, and Orangemen. One major accomplishment of Macdonald's first government was the creation of the Canadian Pacific Railway which also led to the Pacific Scandal that brought down the government in 1873.[7]

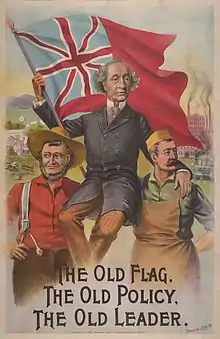

The Liberal-Conservatives under Macdonald returned to power in 1878 by opposing the policy of free trade or reciprocity with the United States and promoting, instead, the National Policy which sought to promote business and develop industry with high tariff protectionist measures as well as settle and develop the west.[8]

The principal difference between the Conservatives and the Liberals in this period and well into the twentieth century was that Conservatives were in favour of imperial preference (a protectionist system in which tariffs would be levied against imports from outside the British Empire) and strong political and legal links with Britain while Liberals promoted free trade and continentalism (that is closer ties to the United States) and greater independence from Britain.[9] Macdonald died in 1891 and, without his leadership, the Conservative coalition began to unravel under the pressure of sectarian tensions between Catholic French Canadians and British imperialists who tended to be anti-French and anti-Catholic. The government's mis-handling of the grievances that aroused the Red River Rebellion and the North-West Rebellion, and its hanging of their leader Louis Riel), and the Manitoba Schools Question exacerbated tensions within the Conservative Party and suppressed much of the support among Quebecois for the Conservative party, a problem only smoothed over by the 1980s.

Free trade between Canada and the U.S. was the major issue of the 1911 election. Wilfrid Laurier's Liberals, in favour of increased trade with the U.S., were swept from power. Robert Borden led a new Tory administration that emphasised a revitalised National Policy and continued strong links to Britain. Borden had built a base in Quebec by allying with anti-Laurier Quebec nationalists, but, in government, tensions between Quebec nationalists and English Canadian imperialists made any grand coalition untenable.[10]

Borden and the Conservative revival

World War I created a further strain as most Quebecers (plus pacifists and many workers, farmers and socialists across the country, especially immigrants) were unenthusiastic about Canadian involvement in what they saw as a foreign, and particularly British, conflict, while Borden's supporters, most living in English Canada, supported Canada's war effort and its policy of conscription of men for the war (see Conscription Crisis of 1917).[11]

The Unionist Party, 1917–1922

National Liberal and Conservative Party

The attempt to turn the Conservatives into a hegemonic party by merging with Liberal-Unionists failed as most Liberals either joined the new Progressive Party of Canada or rejoined the Liberals under its new leader William Lyon Mackenzie King. One critical issue in this split was free trade - farmers were particularly hostile to Tory tariff policy and free trade was a key issue in the creation of the Progressives while the Conscription Crisis destroyed any remaining Conservative base in Quebec for generations, leaving them with even less support than they had before the Union government.

Borden's successor, Arthur Meighen formally attempted to make the Unionist coalition permanent by creating the "National Liberal and Conservative Party" but most Liberals ended up returning to their old party and some Conservatives balked at what they saw as an attempt to destroy the Conservative Party. John Hampden Burnham, MP for Peterborough West, quit the government caucus to sit as an Independent Conservative and resigned his seat in order to contest it in a by-election on his position.

Meighen's party was defeated by the Liberals in the election of 1921 coming in third behind the Progressives. At March 1922 caucus meeting the party voted to revert to its original name of the Liberal-Conservative Party.

The Liberals were reduced to a minority government in the 1925 election. The Conservatives won a plurality of seats in the House of Commons, but King was able to stay in power with the support of the Progressives and form a minority government. King's government was defeated in a vote in the House of Commons within months and Prime Minister King asked Governor-General Byng to call a new election but Byng refused and asked Meighen to form a government.

Meighen's government was defeated three days after taking office by a vote in the Commons, leaving no choice but a new election. The general election produced a Liberal victory. Wiseman argues that Liberals emphasized Canadian nationalism while Conservatives "exuded British imperialist pride". The "King–Byng Affair" played primarily to Canadian nationalist sentiment because it was felt the Governor General, a British government appointee, had overstepped his bounds and that this was a sign of excessive British influence in Canadian politics. The political impact of the King–Byng Affair therefore favoured the Liberals.[12]

Bennett and the Great Depression

Meighen was replaced as Tory leader by R. B. Bennett, a millionaire Calgary businessman at the 1927 leadership convention, the first time a Tory leader was chosen by this method. Bennett led the Conservatives to power in the 1930 election, largely as a result of the inability of the Liberal government (or any government in the western world) to deal with the Great Depression. Bennett promised to end the economic crisis in three days by implementing the old Conservative policy of high tariffs and imperial preference.

When this policy failed to generate the desired result Bennett's government had no alternative plan. The party's pro-business, pro-bank inclinations provided no relief to the millions of unemployed who were now becoming increasingly desperate and agitated. The Conservatives seemed indecisive and unable to cope and rapidly lost the confidence of Canadians becoming a focus of hatred, ridicule and contempt. Car owners who could no longer afford gasoline reverted to having their vehicles pulled by horses and dubbed them "Bennett buggies".[13][14]

R. B. Bennett faced pressure for radical reforms from within and without the party:

- The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), formed in 1932, prepared to fight its first election on a socialist program. The Social Credit movement was gaining supporters in the west and shocked the country by winning the Alberta provincial election and forming government in September, 1935. Bennett's own government suffered a defection as his Trade minister, Henry Herbert Stevens, left the Conservatives to form the Reconstruction Party of Canada when Bennett refused to enact Stevens' plans for drastic economic reform and government intervention in the economy to deal with the crisis.[15]

Bennett attempted to prevent social disorder by evacuating the unemployed to relief camps far away from the cities but this only exacerbated social tensions leading to the "On-to-Ottawa Trek" of unemployed protesters who intended to ride the rails from Vancouver to Ottawa (gathering new members along the way) in order to bring their demands for relief to Bennett personally. The trek ended in Regina on July 1, 1935, when the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, on orders from the Prime Minister, attacked a public meeting of 3,000 strikers leaving two dead and dozens injured.

Bennett had in desperation attempted to save his government by reversing its laissez-faire policies and, belatedly, implementing "Bennett's New Deal" based on the New Deal of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Bennett proposed progressive income taxation, a minimum wage, a maximum for work week hours, unemployment insurance, health insurance, an expanded pension program, and grants to farmers. The Conservatives' conversion to the concept of a welfare state came too late, and the Conservatives were routed in the October 1935 election, winning only 40 seats to 173 for Mackenzie King's Liberals.[14]

The Bennett years left the Conservatives in the worst shape they had ever been – not only did enmity towards the Conservatives continue in Quebec as a legacy of the Conscription Crisis of 1917, but they were now reviled in the West for their perceived insensitivity to the needs of farmers in the Dust Bowl and Westerners turned to Social Credit or the CCF making the Conservatives their fourth choice. The Conservatives would have to wait twenty years before their fortunes in Western Canada revived.[15]

National Government label

Bennett's successor, Robert Manion, was chosen at the 1938 leadership convention which also officially changed the name of the party from the Liberal-Conservative Party to the National Conservative Party.[16] The Conservatives fought the 1940 election under Manion with a different name, "National Government".

With the election taking place during World War II, the party ran on a platform of forming a wartime national unity government. Manion proposed to have Liberal and Labour supporters of the coalition concept run as "National Government" candidates nominated through open riding conventions in which members of any party would be allowed to vote. The concept did not pan out and, in practice, the National Government candidates were all Conservatives. Despite the new name, the party failed to gain any seats, and Manion was personally defeated in his riding.

The idea for running under a "National Government" platform was likely inspired by the Union Government which the Conservatives formed during World War I in coalition with some dissident Liberals.

Decline and reinvention as Progressive Conservatives

After Manion's defeat, the Conservatives again turned to Arthur Meighen for leadership. Senator Meighen was appointed the party's leader for the duration of the war in November 1941 by a unanimous vote at a national conference of several hundred party delegates after a motion to hold a leadership convention was defeated. He resigned from the Senate and attempted to enter the House of Commons from a safe Conservative seat but was trounced by the CCF in a February 1942 by-election in York South. His party's agitation for a re-enactment of conscription in World War II only further alienated Quebec from the Conservatives. Meighen resigned as leader following his defeat.

Later that year, the Conservatives attempted to broaden their base by electing Manitoba Progressive Premier John Bracken as their new leader at the 1942 leadership convention. Bracken agreed to become the party's leader on the condition that it change its name to the "Progressive Conservative Party of Canada".

National Conservative leaders (1867–1942)

| Name | From | To | Riding as leader | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sir John A. Macdonald | July 1, 1867 | June 6, 1891 | Kingston, ON (1867–18, 1887–91); Victoria, BC (1878–82); Carleton, ON (1882–88) |

1st Prime Minister |

|

Sir John Abbott | June 16, 1891 | November 24, 1892 | Senator for Inkerman, QC | 3rd Prime Minister |

|

Sir John Sparrow David Thompson | December 5, 1892 | December 12, 1894 | Antigonish, NS | 4th Prime Minister |

|

Sir Mackenzie Bowell | December 21, 1894 | April 27, 1896 | Senator for Hastings, ON | 5th Prime Minister |

|

Sir Charles Tupper | May 1, 1896 | February 6, 1901 | Cape Breton, NS | 6th Prime Minister |

|

Sir Robert Laird Borden | February 6, 1901 | July 10, 1920 | Halifax, NS (1900–04, 1908–17); Carleton, ON (1905–08); Kings, NS (1917–21) |

8th Prime Minister |

|

Arthur Meighen | July 10, 1920 | September 24, 1926 | Portage la Prairie, MB (1908–21, 1925–26); Grenville, ON (1922–25) |

9th Prime Minister |

|

Hugh Guthrie (interim leader) | October 11, 1926 | October 12, 1927 | Wellington South | |

|

R. B. Bennett | October 12, 1927 | July 7, 1938 | Calgary West, AB | 11th Prime Minister |

|

Robert Manion | July 7, 1938 | May 14, 1940 | London, ON | Resigned after lost seat in 1940 election |

|

Richard Hanson (interim leader) | May 14, 1940 | November 12, 1941 | York—Sunbury, NB | |

|

Arthur Meighen | November 12, 1941 | December 9, 1942 | Senator for St. Marys, Ontario | Resigned after defeat in attempt to enter House of Commons via York South by-election |

Conservative leaders in the Senate

| Name | From | To | Position | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander Campbell | July 1, 1867 | January 26, 1887 | Government Leader. Opposition Leader from November 5, 1873, to October 7, 1878 | |

| Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott | May 12, 1887 | October 30, 1893 | Government Leader | also Prime Minister from June 16, 1891, to November 24, 1892 |

| Sir Mackenzie Bowell | October 31, 1893 | March 1, 1906 | Government Leader | also Prime Minister from December 21, 1894, to April 27, 1896 |

| Sir Mackenzie Bowell | October 31, 1893 | March 1, 1906 | Opposition Leader | |

| Sir James Alexander Lougheed | April 1, 1906 | November 2, 1925 | Opposition Leader, Government Leader from October 10, 1911, to December 28, 1921 | Unionist Party from 1917 to 1920 |

| William Benjamin Ross | January 1, 1926 | January 10, 1929 | Opposition Leader. Government Leader from June 28 to September 24, 1926 | |

| Wellington Bartley Willoughby | January 11, 1929 | February 3, 1932 | Opposition Leader. Government Leader from August 7, 1930 | |

| Arthur Meighen | February 3, 1932 | January 16, 1942 | Government Leader until October 22, 1935. Opposition leader until 1942 | Former prime minister (1920-1921, 1926). Also National Conservative Leader (2nd time) from November 13, 1941 |

| Charles Colquhoun Ballantyne | January 16, 1942 | December 10, 1942 | Opposition Leader | Became Senate Leader when Meighen resigned to run for a seat in the House of Commons. Conservative Party became Progressive Conservative Party of Canada as of December 11, 1942. Ballantyne served as first Progressive Conservative Senate leader until 1945. |

Election results 1867–1940

| Election | Leader | Party name | # of candidates nominated | # of seats won | +/– | Election Outcome | # of total votes | % of popular vote | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1867 | John A. Macdonald | Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives | 112 | 100 / 180 |

92,656 | 34.53% | Majority | ||

| 1872 | Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives, one Conservative Labour | 140 | 100 / 200 |

123,100 | 38.66% | Minority | |||

| 1874 | Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives, one Conservative Labour | 104 | 65 / 206 |

99,440 | 30.58% | Opposition | |||

| 1878 | Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives | 161 | 129 / 206 |

229,191 | 42.06% | Majority | |||

| 1882 | Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives | 168 | 136 / 215 |

208,544 | 40.39% | Majority | |||

| 1887 | Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives | 203 | 111 / 215 |

343,805 | 47.41% | Majority | |||

| 1891 | Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives | 212 | 117 / 215 |

376,518 | 48.58% | Majority | |||

| 1896 | Charles Tupper | Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives | 207 | 98 / 213 |

467,415 | 48.17% | Opposition | ||

| 1900 | Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives | 204 | 79 / 213 |

438,330 | 46.1% | Opposition | |||

| 1904 | Robert Borden | Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives | 205 | 75 / 214 |

470,430 | 45.94% | Opposition | ||

| 1908 | Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives | 211 | 85 / 221 |

539,374 | 46.21% | Opposition | |||

| 1911 | Conservatives, Liberal-Conservatives and Nationalist Conservatives | 212 | 132 / 221 |

636,938 | 48.90% | Majority | |||

| 1917 | Unionist Party | 211 | 152 / 235 |

1,070,694 | 56.93% | Majority | |||

| 1921 | Arthur Meighen | National Liberal and Conservative Party | 204 | 49 / 235 |

935,651 | 29.95% | Third Party | ||

| 1925 | Arthur Meighen | Conservatives | 232 | 114 / 245 |

1,454,253 | 46.13% | Opposition | ||

| Minority | |||||||||

| 1926 | Arthur Meighen | Conservatives | 232 | 91 / 245 |

1,476,834 | 45.34% | Opposition | ||

| 1930 | R. B. Bennett | Conservatives | 229 | 137 / 245 |

1,836,115 | 47.79% | Majority | ||

| 1935 | Conservatives | 228 | 39 / 245 |

1,290,671 | 29.84% | Opposition | |||

| 1940 | Robert James Manion | National Government | 207 | 39 / 245 |

1,402,059 | 30.41% | Opposition |

See also

Notes

- 1 2 "Conservative Party". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ↑ Gwyn, Richard (2011). Nation Maker: Sir John A. Macdonald: His Life, Our Times. Random House Canada.

- ↑ The Protective Tariff in Canada's Development. University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ "Sir John A. Macdonald: A Perfect Rascal?". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ↑ "MEIGHEN, ARTHUR". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Université Laval.

- ↑ "1938 CONSERVATIVE LEADERSHIP CONVENTION". CPAC. Cable Public Access Channel.

- ↑ Donald Creighton, John A. Macdonald: The Old Chieftain. Vol. 2 (1955).

- ↑ Donald V. Smiley, "Canada and the Quest for a National Policy." Canadian Journal of Political Science 8#1 (1975): 40–62.

- ↑ Lowell C. Clark, "The Conservative Party in the 1890s" Report of the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Historical Association / Rapports annuels de la Société historique du Canada, (1961) 40#1 pp. 58–74. online

- ↑ R.C. Brown and Ramsay Cook, Canada, 1896–1921 A Nation Transformed (1974).

- ↑ Robert Craig Brown, Robert Laird Borden: 1914–1937 (1980).

- ↑ Nelson Wiseman (2011). In Search of Canadian Political Culture. UBC Press. pp. 80–.

- ↑ Larry A. Glassford, Reaction and Reform: The Politics of the Conservative Party under R.B. Bennett, 1927–1938 (1992).

- 1 2 John H. Thompson, and Allan Seager, Canada 1922–1939 (1985).

- 1 2 Thompson and Seager, Canada 1922–1939 (1985).

- ↑ "1938 CONSERVATIVE LEADERSHIP CONVENTION". CPAC. Cable Public Access Channel. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

Further reading

- Bothwell, Robert; Ian Drummond. Canada since 1945 (2nd ed. 1989)

- Creighton, Donald. John A. Macdonald: The Old Chieftain. Vol. 2 (1955)

- English, John. The Decline of Politics: The Conservatives and the Party System, 1901–20 (1977)

- Glassford, Larry A. Reaction and Reform: The Politics of the Conservative Party under R. B. Bennett, 1927–1938 (1992).

- Heintzman, Ralph. "The political culture of Quebec, 1840–1960." Canadian Journal of Political Science 16#1 (1983): 3–60.

- Lower, A. R. M. A History of Canada: Colony to Nation (1964)

- McInnis, Edgar. Canada: a Political and Social History (1969)

- Neatby, H. Blair. The Politics of Chaos: Canada in the Thirties (1972)