Daniel Day-Lewis | |

|---|---|

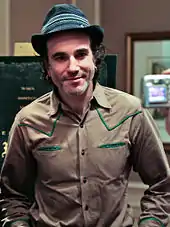

Day-Lewis in 2013 | |

| Born | Daniel Michael Blake Day-Lewis 29 April 1957 London, England |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | Bristol Old Vic Theatre School |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1971–2017 |

| Spouse | |

| Partner | Isabelle Adjani (1989–1995) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Full list |

Sir Daniel Michael Blake Day-Lewis (born 29 April 1957) is an English retired actor.[1] Often described as one of the greatest actors in the history of cinema,[2][3][4][5] he received numerous accolades throughout his career which spanned over four decades, including three Academy Awards, four BAFTA Awards, three Screen Actors Guild Awards and two Golden Globe Awards. In 2014, Day-Lewis received a knighthood for services to drama.[6]

Born and raised in London, Day-Lewis excelled on stage at the National Youth Theatre before being accepted at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, which he attended for three years. Despite his traditional training at the Bristol Old Vic, he is considered a method actor, known for his constant devotion to and research of his roles.[7][8] Protective of his private life, he rarely grants interviews, and makes very few public appearances.[9]

Day-Lewis shifted between theatre and film for most of the early 1980s, joining the Royal Shakespeare Company and playing Romeo Montague in Romeo and Juliet and Flute in A Midsummer Night's Dream. Playing the title role in Hamlet at the National Theatre in London in 1989, he left the stage midway through a performance after breaking down during a scene where the ghost of Hamlet's father appears before him—this was his last appearance on the stage.[10] After supporting film roles in Gandhi (1982), and The Bounty (1984), he earned acclaim for his breakthrough performances in My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), A Room with a View (1985), and The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988).

He earned Academy Awards for his roles in My Left Foot (1989), There Will Be Blood (2007), and Lincoln (2012). His other Oscar-nominated roles were in In the Name of the Father (1993), Gangs of New York (2002), and Phantom Thread (2017). Other notable films include The Last of the Mohicans (1992), The Age of Innocence (1993), The Crucible (1996), and The Boxer (1997). He retired from acting from 1997 to 2000, taking up a new profession as an apprentice shoe-maker in Italy. Although he returned to acting, he announced his retirement again in 2017.[11][12]

Early life and education

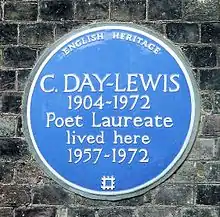

Daniel Michael Blake Day-Lewis was born on 29 April 1957 in Kensington, London, the second child of poet Cecil Day-Lewis (1904–1972) and his second wife, actress Jill Balcon (1925–2009). His older sister, Tamasin Day-Lewis (born 1953), is a television chef and food critic.[13] His father, who was born in the Irish town of Ballintubbert, County Laois, was of Protestant Anglo-Irish descent, lived in England from age two, and was appointed Poet Laureate in 1968.[14] Day-Lewis's mother was Jewish; her Jewish ancestors were immigrants to England in the late 19th century, from Latvia and Poland.[15][16][17][18] Day-Lewis's maternal grandfather, Sir Michael Balcon, became the head of Ealing Studios, helping develop the new British film industry.[19] The BAFTA for Outstanding Contribution to British Cinema is presented every year in honour of Balcon's memory.[20]

Two years after Day-Lewis's birth, he moved with his family to Croom's Hill in Greenwich via Port Clarence, County Durham. He and his older sister did not see much of their older two half-brothers, who had been teenagers when Day-Lewis's father divorced their mother.[21] Living in Greenwich (he attended Invicta and Sherington Primary Schools),[22] Day-Lewis had to deal with tough South London children. At this school, he was bullied for being both Jewish and "posh".[23][24] He mastered the local accent and mannerisms, and credits that as being his first convincing performance.[24][25] Later in life, he has been known to speak of himself as a disorderly character in his younger years, often in trouble for shoplifting and other petty crimes.[25][26]

In 1968, Day-Lewis's parents, finding his behaviour to be too wild, sent him as a boarder to the independent Sevenoaks School in Kent.[26] At the school, he was introduced to his three most prominent interests: woodworking, acting, and fishing. However, his disdain for the school grew, and after two years at Sevenoaks, he was transferred to another independent school, Bedales in Petersfield, Hampshire.[27] His sister was already a student there, and it had a more relaxed and creative ethos.[26] He made his film debut at age 14 in Sunday Bloody Sunday, in which he played a vandal in an uncredited role. He described the experience as "heaven" for getting paid £2 to vandalise expensive cars parked outside his local church.[21]

For a few weeks in 1972, the Day-Lewis family lived at Lemmons, the north London home of Kingsley Amis and Elizabeth Jane Howard. Day-Lewis's father had pancreatic cancer, and Howard invited the family to Lemmons as a place they could use to rest and recuperate. His father died there in May that year.[28] By the time he left Bedales in 1975, Day-Lewis's unruly attitude had diminished and he needed to make a career choice. Although he had excelled on stage at the National Youth Theatre in London, he applied for a five-year apprenticeship as a cabinet-maker. He was turned down due to a lack of experience.[26] He was accepted at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, which he attended for three years along with Miranda Richardson, eventually performing at the Bristol Old Vic itself.[26] At one point he played understudy to Pete Postlethwaite, with whom he would later co-star in the film In the Name of the Father (1994).[29]

John Hartoch, Day-Lewis's acting teacher at Bristol Old Vic, recalled:

There was something about him even then. He was quiet and polite, but he was clearly focused on his acting—he had a burning quality. He seemed to have something burning beneath the surface. There was a lot going on beneath that quiet appearance. There was one performance in particular, when the students put on a play called Class Enemy, when he really seemed to shine—and it became obvious to us, the staff, that we had someone rather special on our hands.[30]

Career

1980s

During the early 1980s, Day-Lewis worked in theatre and television, including Frost in May (where he played an impotent man-child) and How Many Miles to Babylon? (as a World War I officer torn between allegiances to Britain and Ireland) for the BBC. Eleven years after his film debut, Day-Lewis had a small part in the film Gandhi (1982) as Colin, a South African street thug who racially bullies the title character. In late 1982, he had his big theatre break when he took over the lead in Another Country, which had premiered in late 1981. Next, he took on a supporting role as the conflicted, but ultimately loyal, first mate in The Bounty (1984). He next joined the Royal Shakespeare Company, playing Romeo in Romeo and Juliet and Flute in A Midsummer Night's Dream.[26]

In 1985, Day-Lewis gave his first critically acclaimed performance playing a young gay English man in an interracial relationship with a Pakistani youth in the film My Beautiful Laundrette. Directed by Stephen Frears, and written by Hanif Kureishi, the film is set in 1980s London during Margaret Thatcher's tenure as Prime Minister.[9] It is the first of three Day-Lewis films to appear in the BFI's 100 greatest British films of the 20th century, ranking 50th.[31]

Day-Lewis gained further public notice that year with A Room with a View (1985), based on the novel by E. M. Forster. Set in the Edwardian period of turn-of-the-20th-century England, he portrayed an entirely different character: Cecil Vyse, the proper upper-class fiancé of the main character.[32] In 1987, Day-Lewis assumed leading man status by starring in Philip Kaufman's adaptation of Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being, in which he portrayed a Czech surgeon whose hyperactive sex life is thrown into disarray when he allows himself to become emotionally involved with a woman. During the eight-month shoot, he learned Czech, and first began to refuse to break character on or off the set for the entire shooting schedule.[26] During this period, Day-Lewis was regarded as "one of Britain’s most exciting young actors".[33] He and other young British actors of the time, such as Gary Oldman, Colin Firth, Tim Roth, and Bruce Payne, were dubbed the "Brit Pack".[34]

Day-Lewis progressed his personal version of method acting in 1989 with his performance as Christy Brown in Jim Sheridan's My Left Foot. It won him numerous awards, including the Academy Award for Best Actor and BAFTA Award for Best Actor. Brown, known as a writer and painter, was born with cerebral palsy, and was able to control only his left foot.[35] Day-Lewis prepared for the role by making frequent visits to Sandymount School Clinic in Dublin, where he formed friendships with several people with disabilities, some of whom had no speech.[36] During filming, he again refused to break character.[26] Playing a severely paralysed character on screen, off screen Day-Lewis had to be moved around the set in his wheelchair, and crew members would curse at having to lift him over camera and lighting wires, all so that he might gain insight into all aspects of Brown's life, including the embarrassments.[25] Crew members were also required to spoon-feed him.[35] It was rumoured that he had broken two ribs during filming from assuming a hunched-over position in his wheelchair for so many weeks, something he denied years later at the 2013 Santa Barbara International Film Festival.[37]

.jpg.webp)

Day-Lewis returned to the stage in 1989 to work with Richard Eyre, as the title character in Hamlet at the National Theatre, London, but during a performance collapsed during the scene where the ghost of Hamlet's father appears before him.[26] He began sobbing uncontrollably, and refused to go back on stage; he was replaced by Jeremy Northam, who gave a triumphant performance.[33] Ian Charleson formally replaced Day-Lewis for the rest of the run.[38] Earlier in the run, Day-Lewis had talked of the "demons" in the role, and for weeks he threw himself passionately into the part.[33] Although the incident was officially attributed to exhaustion, Day-Lewis claimed to have seen the ghost of his own father.[26][39] He later explained that this was more of a metaphor than a hallucination. "To some extent I probably saw my father’s ghost every night, because of course if you’re working in a play like Hamlet, you explore everything through your own experience."[40] He has not appeared on stage since.[41] The media attention following his breakdown on-stage contributed to his decision to eventually move from England to Ireland in the mid-1990s, to regain a sense of privacy amidst his increasing fame.[42]

1990s

Day-Lewis starred in the American film The Last of the Mohicans (1992), based on a novel by James Fenimore Cooper. Day-Lewis's character research for this film was well-publicised; he reportedly underwent rigorous weight training, and learned to live off the land and forest where his character lived, camping, hunting, and fishing.[26] Day-Lewis also added to his wood-working skills, and learned how to make canoes.[43] He carried a long rifle at all times during filming to remain in character.[26][44]

Stories of his immersion in roles are legion. Playing Gerry Conlon in In the Name of the Father, Day-Lewis lived on prison rations to lose 30 lb, spent extended periods in the jail cell on set, went without sleep for two days, was interrogated for three days by real policemen, and asked that the crew hurl abuse and cold water at him. For The Boxer in 1997, he trained for weeks with the former world champion Barry McGuigan, who said that he became good enough to turn professional. The actor's injuries include a broken nose and a damaged disc in his lower back.

—"Daniel Day-Lewis aims for perfection". Article published in The Daily Telegraph on 22 February 2008[35]

He returned to work with Jim Sheridan on In the Name of the Father in which he played Gerry Conlon, one of the Guildford Four, who were wrongfully convicted of a bombing carried out by the Provisional IRA. He lost 2st 2 lb (30 lb or 14 kg) for the part, kept his Northern Irish accent on and off the set for the entire shooting schedule, and spent stretches of time in a prison cell.[44] He insisted that crew members throw cold water at him and verbally abuse him.[44] Starring opposite Emma Thompson (who played his lawyer Gareth Peirce), and Pete Postlethwaite, Day-Lewis earned his second Academy Award nomination, third BAFTA nomination, and second Golden Globe nomination.[45]

Day-Lewis returned to the US in 1993, playing Newland Archer in Martin Scorsese's adaptation of the Edith Wharton novel The Age of Innocence. Day-Lewis starred opposite Michelle Pfeiffer, and Winona Ryder. To prepare for the film, set in America's Gilded Age, he wore 1870s-period aristocratic clothing around New York City for two months, including top hat, cane, and cape.[46] Although Day-Lewis was sceptical of the role, thinking himself "too English" for it and hoping for something "more rough-and-tumble", he accepted due to Scorsese directing the film.[47] The film was critically well received, while Peter Travers in Rolling Stone wrote: "Day-Lewis is smashing as the man caught between his emotions and the social ethic. Not since Olivier in Wuthering Heights has an actor matched piercing intelligence with such imposing good looks and physical grace."[48]

In 1996, Day-Lewis starred in the film adaptation of Arthur Miller's play The Crucible reunited with Winona Ryder, and starring alongside Paul Scofield, and Joan Allen. During the shoot, he met his future wife, Rebecca Miller, the author's daughter.[49] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly gave the film a grade of "A", calling the adaptation "joltingly powerful" and noting the "spectacularly" acted performances of Day-Lewis, Scofield, and Allen.[50] He followed that with Jim Sheridan's The Boxer alongside Emily Watson, starring as a former boxer and IRA member recently released from prison. His preparation included training with former boxing world champion Barry McGuigan. Immersing himself into the boxing scene, he watched "Prince" Naseem Hamed train, and attended professional boxing matches such as the Nigel Benn vs. Gerald McClellan world title fight at London Arena.[51][52] Impressed with his work in the ring, McGuigan felt Day-Lewis could have become a professional boxer, commenting, "If you eliminate the top ten middleweights in Britain, any of the other guys Daniel could have gone in and fought."[40]

Following The Boxer, Day-Lewis took a leave of absence from acting by going into "semi-retirement" and returning to his old passion of wood-working.[51] He moved to Florence, Italy, where he became intrigued by the craft of shoe-making. He apprenticed as a shoe-maker with Stefano Bemer.[26] For a time, his exact whereabouts and actions were not made publicly known.[53]

2000s

After a three-year absence from acting on screen, Day-Lewis returned to film by reuniting with Martin Scorsese for Gangs of New York (2002). He took on the role of villainous gang leader William "Bill the Butcher" Cutting, starring opposite Leonardo DiCaprio, who played Bill's young protégé as well as Cameron Diaz, Jim Broadbent, John C. Reilly, Brendan Gleeson, and Liam Neeson. To help him get into character, he hired circus performers to teach him to throw knives.[35] While filming, he was never out of character between takes (including keeping his character's New York accent).[26] At one point during filming, having been diagnosed with pneumonia, he refused to wear a warmer coat, or to take treatment, because it was not in keeping with the period; he was eventually persuaded to seek medical treatment.[35] The film divided critics while Day-Lewis received plaudits for his portrayal of Bill the Butcher. Rotten Tomatoes's critical consensus reads, "Though flawed, the sprawling, messy Gangs of New York is redeemed by impressive production design and Day-Lewis's electrifying performance."[54] It earned Day-Lewis his third Oscar nomination, and won him his second BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role.[55]

In the early 2000s, Day-Lewis's wife, director Rebecca Miller, offered him the lead role in her film The Ballad of Jack and Rose, in which he played a dying man with regrets over how his life had evolved, and over how he had brought up his teenage daughter. While filming, he arranged to live separately from his wife to achieve the "isolation" needed to focus on his own character's reality.[21] The film received mixed reviews.[56]

In 2007, Day-Lewis starred alongside Paul Dano in Paul Thomas Anderson's loose film adaptation of Upton Sinclair's novel Oil!, titled There Will Be Blood.[57] The film received widespread critical acclaim, with critic Andrew Sarris calling the film "an impressive achievement in its confident expertness in rendering the simulated realities of a bygone time and place, largely with an inspired use of regional amateur actors and extras with all the right moves and sounds."[58] Day-Lewis received the Academy Award for Best Actor, BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role, Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama, Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role (which he dedicated to Heath Ledger, who had died five days earlier, saying he was inspired by Ledger's acting and calling the actor's performance in Brokeback Mountain "unique, perfect"),[59][60] and a variety of film critics' circle awards for the role. In winning the Best Actor Oscar, Day-Lewis joined Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson as the only Best Actor winner awarded an Oscar in two non-consecutive decades.[61]

In 2009, Day-Lewis starred in Rob Marshall's musical adaptation Nine as film director Guido Contini.[62] The film featured a large ensemble of distinguished actresses, including Marion Cotillard, Penélope Cruz, Judi Dench, Nicole Kidman, and Sophia Loren. The film received mixed reviews, with overall praise for the performances of Day-Lewis, Cotillard, and Cruz. He was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy and the Satellite Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy for his role, as well as sharing nominations for the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture and the Broadcast Film Critics Association Award for Best Cast and the Satellite Award for Best Cast – Motion Picture with the rest of the cast members.[63][64]

2010s

Day-Lewis portrayed Abraham Lincoln in Steven Spielberg's biopic Lincoln (2012).[65] Based on the book Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, the film began shooting in Richmond, Virginia, in October 2011.[66] Day-Lewis spent a year in preparation for the role, a time he had requested from Spielberg.[67] He read over 100 books on Lincoln, and long worked with the make-up artist to achieve a physical likeness to Lincoln. Speaking in Lincoln's voice throughout the entire shoot, Day-Lewis asked the British crew members who shared his native accent not to chat with him.[2] Spielberg said of Day-Lewis's portrayal, "I never once looked the gift horse in the mouth. I never asked Daniel about his process. I didn't want to know."[40] Lincoln received critical acclaim, especially for Day-Lewis's performance. It also became a commercial success, grossing over $275 million worldwide.[68] In November 2012, he received the BAFTA Britannia Award for Excellence in Film.[69] The same month, Day-Lewis featured on the cover of Time magazine as the "World's Greatest Actor".[70]

He's like Olivier in his prime. [Because he does so few movies], you expect something spectacular when he's got a film out. He's more selective than Brando, and it's turned his movies into events.

—David Poland on Day-Lewis, February 2013[3]

At the 70th Golden Globe Awards, on 14 January 2013, Day-Lewis won his second Golden Globe Award for Best Actor, and at the 66th British Academy Film Awards on 10 February, he won his fourth BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role. At the 85th Academy Awards, Day-Lewis became the first three-time recipient of the Best Actor Oscar for his role in Lincoln.[71] John Hartoch, Day-Lewis's acting teacher at Bristol Old Vic theatre school, said of his former pupil's achievement:

Although we have quite an impressive alumni – everyone from Jeremy Irons to Patrick Stewart – I suppose he is now probably the best known, and we're very proud of all he's achieved. I certainly hold him up to current students of an example, particularly as an example of how to manage your career with great integrity. He's never courted fame, and as a result, he's never had his private life impeached upon by the press. He's clearly not interested in celebrity as such – he's just interested in his acting. He is still a great craftsman.[30]

Shortly after winning the Oscar for Lincoln, Day-Lewis announced he would be taking a break from acting, retreating back to his Georgian farmhouse in County Wicklow, Ireland, for the next five years, before making another film.[72] After a five-year hiatus, Day-Lewis returned to the screen to star in Paul Thomas Anderson's historical drama Phantom Thread (2017). Set in 1950s London, Day-Lewis played an obsessive dressmaker, Reynolds Woodcock, who falls in love with a waitress (played by Vicky Krieps).[73] Prior to the film's release, on 20 June 2017, Day-Lewis's spokeswoman, Leslee Dart, announced that he was retiring from acting.[11][74] Unable to give an exact reason for his decision, in a November 2017 interview, Day-Lewis stated: "I haven't figured it out. But it's settled on me, and it's just there ... I dread to use the over-used word 'artist', but there's something of the responsibility of the artist that hung over me. I need to believe in the value of what I'm doing. The work can seem vital, irresistible, even. And if an audience believes it, that should be good enough for me. But, lately, it isn't."[75] On Day-Lewis's retirement, Anderson stated, "I would like to hope that he just needs a break. But I don't know. It sure doesn't seem like it right now, which is a big drag for all of us."[40] The film and his performance were met with widespread acclaim from critics, and Day-Lewis was again nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor.[76]

Technique and reputation

Day-Lewis is considered a method actor, known for his constant devotion to and research of his roles.[7][8] Displaying a "mercurial intensity", he would often remain completely in character throughout the shooting schedules of his films, even to the point of adversely affecting his health.[5][35] He is one of the most selective actors in the film industry, having starred in only six films since 1998, with as many as five years between roles.[77] Protective of his private life, he rarely grants interviews, and makes very few public appearances.[9]

Following his third Oscar win in 2013, there was much debate about Day-Lewis's standing among the greatest actors in film history.[2][3][4][78] Joe Queenan of The Guardian remarked, "Arguing whether Daniel Day-Lewis is a greater actor than Laurence Olivier, or Richard Burton, or Marlon Brando, is like arguing whether Messi is more talented than Pelé, whether Napoleon Bonaparte edges out Alexander the Great as a military genius."[4] When Day-Lewis himself was asked what it was like to be "the world's greatest actor", he replied, "It's daft isn't it? It changes all the time."[79]

Widely respected among his peers, in June 2017, Michael Simkins of The Guardian wrote, "In this glittering cesspit we call the acting profession, there are plenty of rival thesps who, through sheer luck or happenstance, seem to have the career we ourselves could have had if only the cards had fallen differently. But Day-Lewis is, by common consent, even in the most sourly disposed green rooms – a class apart. We shall not look upon his like again – at least for a bit. Performers of his mercurial intensity come along once in a generation."[5]

Personal life

.jpg.webp)

Protective of his privacy, Day-Lewis has described his life as a "lifelong study in evasion".[80] He had a relationship with French actress Isabelle Adjani that lasted six years, eventually ending after a split and reconciliation.[7] Their son, Gabriel-Kane Day-Lewis, was born in 1995 in New York City a few months after the relationship ended.[81]

In 1996, while working on the film version of the stage play The Crucible, he visited the home of playwright Arthur Miller, where he was introduced to the writer's daughter, Rebecca Miller.[7] They married later that year, on 13 November 1996.[82] The couple have two sons, Ronan Cal Day-Lewis (born 1998) and Cashel Blake Day-Lewis (born 2002). They divide their time between their homes in Manhattan and Annamoe, Ireland.[21][83]

Day-Lewis has held dual British and Irish citizenship since 1993.[84] He has maintained his Annamoe home since 1997.[83][85][86] He stated: "I do have dual citizenship, but I think of England as my country. I miss London very much, but I couldn't live there because there came a time when I needed to be private and was forced to be public by the press. I couldn't deal with it."[80] He is a supporter of South East London football club Millwall.[87] Day-Lewis is also an Ambassador for The Lir Academy, a new drama school at Trinity College Dublin, founded in 2011.[88]

In 2010, Day-Lewis received an honorary doctorate in letters from the University of Bristol, in part because of his attendance of the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School in his youth.[89] Day-Lewis has stated that he had "no real religious education", and that he "suppose[s]" he is "a die-hard agnostic".[90] In 2012, he donated to the University of Oxford papers belonging to his father, the poet Cecil Day-Lewis, including early drafts of the poet's work and letters from actor John Gielgud and literary figures such as W. H. Auden, Robert Graves, and Philip Larkin.[91] In 2015, he became the Honorary President of the Poetry Archive. A registered UK charity, the Poetry Archive is a free website containing a growing collection of recordings of English-language poets reading their work.[92] In 2017, Day-Lewis became a patron of the Wilfred Owen Association.[93] Day-Lewis's association with Wilfred Owen began with his father, Cecil Day-Lewis, who edited Owen's poetry in the 1960s and his mother, Jill Balcon, who was a vice-president of the Wilfred Owen Association until her death in 2009.[94][95]

In 2008, when he received the Academy Award for Best Actor from Helen Mirren (who was on presenting duty having won the previous year's Best Actress Oscar for portraying Queen Elizabeth II in The Queen), Day-Lewis knelt before her, and she tapped him on each shoulder with the Oscar statuette, to which he quipped, "That's the closest I'll come to ever getting a knighthood."[96] Day-Lewis was appointed a Knight Bachelor in the 2014 Birthday Honours for services to drama.[6][97] On 14 November 2014, he was knighted by Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, in an investiture ceremony at Buckingham Palace.[98][99]

Acting credits

Film

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Shoestring | DJ | Episode: "The Farmer Had a Wife" |

| 1981 | Thank You, P. G. Wodehouse | Psmith | Television film |

| 1981 | Artemis 81 | Library Student | Television film |

| 1982 | How Many Miles to Babylon? | Alec | Television film |

| 1982 | Frost in May | Archie Hughes-Forret | Episode: "Beyond the Glass" |

| 1983 | Play of the Month | Gordon Whitehouse | Episode: "Dangerous Corner" |

| 1985 | My Brother Jonathan | Jonathan Dakers | 5 episodes |

| 1986 | Screen Two | Dr. Kafka | Episode: "The Insurance Man" |

Theatre

| Year(s) | Title | Role | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | The Recruiting Officer | Townsperson/Soldier | Theatre Royal, Bristol |

| 1979 | Troilus and Cressida | Deiphobus | Theatre Royal, Bristol |

| 1979 | Funny Peculiar | Stanley Baldry | Little Theatre, Bristol |

| 1979–80 | Old King Cole | The Amazing Faz | Old Vic Theatre, Bristol |

| 1980 | Class Enemy | Iron | Old Vic Theatre, Bristol |

| 1980 | Edward II | Leicester | Old Vic Theatre, Bristol |

| 1980 | Oh, What a Lovely War! | Unknown | Theatre Royal, Bristol |

| 1980 | A Midsummer Night's Dream | Philostrate | Theatre Royal, Bristol |

| 1981 | Look Back in Anger | Jimmy Porter | Little Theatre, Bristol |

| 1981 | Dracula | Count Dracula | Little Theatre, Bristol |

| 1982–83 | Another Country | Guy Bennett | Queen's Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue |

| 1983–84 | A Midsummer Night's Dream Romeo and Juliet |

Flute Romeo |

Royal Shakespeare Company |

| 1984 | Dracula | Count Dracula | Half Moon Theatre, London |

| 1986 | Futurists | Volodya Mayakovsky | Royal National Theatre, London |

| 1989 | Hamlet | Hamlet | Royal National Theatre, London |

Music

| Year | Title | Role |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | The Ballad of Jack and Rose | Original score producer |

| 2009 | Nine | Performer on "Guido's Song", "I Can't Make This Movie" |

Awards and nominations

He has received numerous accolades throughout his career which spanned over four decades, including three Academy Awards for Best Actor, making him the first and only actor to have three wins in that category, and the third male actor to win three competitive Academy Awards for acting, the sixth performer overall.[100][lower-alpha 1] Additionally, he has received four British Academy Film Awards, three Screen Actors Guild Awards and two Golden Globe Awards. In 2014, Day-Lewis received a knighthood for services to drama.[6]

See also

- List of people on the postage stamps of Ireland

- List of Academy Award records

- List of British Academy Award nominees and winners

- List of Irish Academy Award winners and nominees

- List of oldest and youngest Academy Award winners and nominees – Youngest winners for Best Actor in a Leading Role

- List of actors with Academy Award nominations

- List of actors with two or more Academy Award nominations in acting categories

- List of actors with two or more Academy Awards in acting categories

- List of superlative Academy Award winners and nominees

- List of Jewish Academy Award winners and nominees

Notes

- ↑ Day-Lewis was only after Katharine Hepburn (who has four in total), Walter Brennan, Ingrid Bergman, Jack Nicholson, and Meryl Streep.[101]

References

- ↑ Appelo, Tim (8 November 2012). "Daniel Day-Lewis Spoofs Clint Eastwood's Obama Chair Routine at Britannia Awards (Video)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

I know as an Englishman it's absolutely none of my business.

- 1 2 3 "Daniel Day-Lewis: the greatest screen actor ever?". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- 1 2 3 Bowles, Scott (24 February 2013). "Is Daniel Day-Lewis now the greatest actor of all time?". USA Today. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Queenan, Joe (25 February 2013). "Oscars 2013: do his three Oscars make Daniel Day-Lewis the greatest?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 Simkins, Michael (22 June 2017). "Actors usually envy each other. But Daniel Day-Lewis is a class apart". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

Most of us would start any list of those few truly exceptional actors – the shape-shifters as they are sometimes called, individuals who can inhabit another character in its entirety without ever lapsing into impersonation – with Marlon Brando, then veer off into a truculent debate about whether Laurence Olivier was the greatest of them all or just an old ham with stale tricks. Robert De Niro would get a mention of course – Meryl Streep, no doubt. But almost everyone would finish with Day-Lewis.

- 1 2 3 "Queen's Honours: Day-Lewis receives knighthood". BBC News. 13 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Gritten, David (22 February 2013). "Daniel Day-Lewis: the greatest screen actor ever?". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- 1 2 Parker, Emily (23 January 2008). "Sojourner in Other Men's Souls". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 Rainey, Sarah (1 March 2013). "My brother Daniel Day-Lewis won't talk to me any more". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ↑ "Did Daniel Day-Lewis see his father's ghost as Hamlet? That is the question …". The Guardian. 12 October 2012. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- 1 2 "Film star Daniel Day-Lewis retires from acting". BBC News. 21 June 2017. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis announces retirement from acting". The Guardian. 20 June 2017. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ↑ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Peter Stanford (2007). "C Day-Lewis: A Life". p. 5. A&C Black

- ↑ Hasted, Nick (31 January 2018). "Daniel Day-Lewis: Why Britain has just lost its De Niro". The Independent. Archived from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ↑ David, Keren (29 November 2017). "Daniel Day-Lewis opens up on his decision to quit acting". The Jewish Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ↑ Jackson, Laura (2005). Daniel Day-Lewis: the biography. Blake. p. 3. ISBN 1-85782-557-8.

Michael Balcon's family were Latvian refugees from Riga who had come to England in the second half of the 19th century. The family of his wife, Aileen Leatherman, whom he married in 1924, came from Poland.

- ↑ "Day-Lewis gets Oscar nod for new film". Kent News. 17 December 2007. Archived from the original on 1 February 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- ↑ Pearlman, Cindy (30 December 2007). "Day-Lewis isn't suffering: 'It's a joy'". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- ↑ "Curzon | Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema". www.bafta.org. 31 January 2017. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Segal, David (31 March 2005). "Daniel Day-Lewis, Behaving Totally In Character". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ "Things You Might Not Have Done In Greenwich: Go on a Daniel Day-Lewis Tour". Information Society. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ↑ "Where did you go to, my lovely?". The Independent. 16 February 1997. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- 1 2 Corliss, Richard (21 March 1994). "Cinema: Dashing Daniel". Time. Archived from the original on 11 April 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 Jenkins, Garry. Daniel Day-Lewis: The Fires Within Archived 27 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine. St. Martin's Press, 1994, ASIN B000R9II4O

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Daniel Day-Lewis – Biography". TalkTalk. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2006.

- ↑ "The Tatler List". Tatler. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016.

- ↑ Sansom, Ian (3 April 2010). "Great dynasties of the world: The Day-Lewises". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ↑ Wolf, Matt (13 March 1994). "FILM; Pete Postlethwaite Turns a Prison Stint Into Oscar Material". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- 1 2 "Bristol Old Vic teacher who taught Daniel Day-Lewis recalls stars early days". Bristol Post. 27 May 2016. Archived from the original on 25 December 2015.

- ↑ "British Film Institute – Top 100 British Films". cinemarealm.com. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis". The Oscar Site. Archived from the original on 7 October 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- 1 2 3 Vidal, John (18 September 1989). "A Punishing System's Stress Chews Up Another Hamlet". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Stern, Marlow (8 December 2011). "Gary Oldman Talks "Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy", "Batman" Retirement". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Daniel Day-Lewis aims for perfection". The Daily Telegraph. London. 22 February 2008. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ↑ Jordan, Anthony J. (2008). The Good Samaritans – Memoir of a Biographer. Westport Books. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-9524447-5-6.

- ↑ An Inspirational Journey: The Making of My Left Foot DVD, Miramax Films, 2005

- ↑ Peter, John. "A Hamlet Who Would Be King at Elsinore". Sunday Times. 12 November 1989.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis Q&A". Time Out. 20 March 2006. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Daniel Day-Lewis: 10 defining roles from the method master". BBC. 31 January 2018. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ↑ Miller, Julie (20 June 2017). "Daniel Day-Lewis Quits Acting: A History of His Fascinating Retirement Attempts". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ↑ Jessica Winter (20 January 2013). "Daniel Day-Lewis". The Observer Magazine.

- ↑ Macnab, Geoffrey (25 February 2013). "The madness of Daniel Day-Lewis – a unique Method that has led to a deserved third Oscar". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Daniel Day-Lewis". tcm.com. Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ↑ Fox, David J. (10 February 1994). "Oscar's Favorite 'List' : The Nominations : 'Schindler's' Sweeps Up With 12 Nods : 'The Piano' and 'The Remains of the Day' both receive eight nominations; 'Fugitive,' 'In the Name of the Father' earn seven". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis". Hello!. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ↑ Hirschberg, Lynn (8 December 2007). "Daniel Day-Lewis: the perfectionist". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ↑ Travers, Peter (16 September 1993). "The Age of Innocence: Review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis | Ryder's Romances Winona's long list of loves lost | MSN Arabia Photo Gallery". Arabia.msn.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ Owen Gleiberman (29 November 1996). "Movie Review: 'The Crucible'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- 1 2 "Daniel Day-Lewis". AskMen. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ↑ McGuigan, Barry (22 January 2007). "McClellan's return must get the game to care more". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ Rebecca Flint Marx (2016). "Daniel Day Lewis: Biography". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ "Gangs of New York (2002)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. 20 December 2002. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ↑ Allison, Rebecca (24 February 2003). "Britain's big Bafta night as The Hours has the edge on Hollywood blockbusters". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ↑ "The Ballad of Jack and Rose". Rotten Tomatoes. 25 March 2005. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ↑ Fleming, Michael; Mohr, Ian (17 January 2006). ""Blood" lust for Par and Miramax". Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ Sarris, Andrew (17 December 2007). "Oil, Oil Everywhere!". The New York Observer.

- ↑ Diluna, Amy; Joe Neumaier (27 January 2008). "Daniel Day-Lewis Honors Heath Ledger during Screen Actors Guild Awards". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ↑ Elsworth, Catherine (28 January 2008). "Daniel Day Lewis, Julie Christie win at Screen Actors Guild Awards". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- ↑ Jackson, Laura (2013). Daniel Day-Lewis – The Biography. John Blake Publishing.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis Signed for Nine Film; Rehearsals to Start in July; Shooting September". BroadwayWorld. 1 June 2008. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ Karger, Dave (15 December 2009). "Golden Globe nominations announced". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 14 January 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- ↑ "14th Annual Satellite Awards". pressacademy.com. International Press Academy. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ Shoard, Catherine (19 November 2010). "Daniel Day-Lewis set for Steven Spielberg's Lincoln film". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ↑ McClintock, Pamela (12 October 2011). "Participant Media Boarding Steven Spielberg's 'Lincoln' (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ↑ Zakarin, Jordan (26 October 2012). "At 'Lincoln' Screening, Daniel Day-Lewis Explains How He Formed the President's Voice". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis Reveals How He Brought Lincoln To Life". ukscreen.com. 13 November 2012. Archived from the original on 17 November 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ "Britannia Award Honorees – Awards & Events – Los Angeles – The BAFTA site". bafta.org. British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA). Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Winter, Jessica (5 November 2012). "The World's Greatest Actor". Time. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ "Day-Lewis wins record third best actor Oscar". The Huffington Post. Associated Press. 25 February 2013. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis wants break from acting". NDTV Movies. 3 March 2013. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ↑ King, Susan (12 January 2018). "Paul Thomas Anderson's "Phantom Thread" is one in a long line of Hollywood films on obsessive love". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ Lang, Brent (20 June 2017). "Shocker! Daniel Day-Lewis Quits Acting (Exclusive)". Variety. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ↑ Nyren, Erin (28 November 2017). "Daniel Day-Lewis on Retirement From Acting: 'The Impulse to Quit Took Root in Me'". Variety. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ↑ "Phantom Thread (2018)". Rotten Tomatoes. 19 January 2018. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ↑ Hirschberg, Lynn (11 November 2007). "The New Frontier's Man". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ Dargis, Manohla; Scott, A.O. (25 November 2020). "The 25 greatest actors of the 21st century (so far)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ↑ Allen, Nick (25 February 2013). "Oscars 2013: Daniel Day-Lewis says it is 'daft' to call him best actor ever". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- 1 2 Stanford, Peter (13 January 2008). "The enigma of Day-Lewis". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ Watson, Shane (15 August 2004). "The dumping game". The Times. UK. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ↑ Achath, Sati (13 May 2011). Hollywood Celebrities: Basic Things You've Always Wanted to Know. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4634-1157-2.

- 1 2 O'Brien, Jason (28 April 2009). "Daniel Day Lewis given Freedom of Wicklow". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ↑ Devlin, Martina (24 January 2008). "Daniel, old chap, sure you're one of our own". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ "Day-Lewis heads UK Oscars charge". BBC News. 22 January 2008. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ Sullivan, Chris (1 February 2008). "How Daniel Day-Lewis' notoriously rigorous role preparation has yielded another Oscar contender". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ "People". The Lir Academy. Archived from the original on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ↑ "Bristol University | News from the University | Honorary degrees". Bristol.ac.uk. 15 July 2010. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis, 2002". Index Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis: Gives poet dad's work to Oxford". The Washington Times. 30 October 2012. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ "Sir Daniel Day-Lewis is to be the new Honorary President of the Poetry Archive". The Poetry Archive. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ Stewart, Stephen (27 June 2017). "Legendary 'ghost' war poet returns from World War One killing fields to meet today's veterans". Daily Record. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis reads Wilfred Owen works in War Poets Collection". BBC News. 1 November 2016. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ "Stars bring war poetry to life". napier.ac.uk. Edinburgh Napier University. 2 November 2016. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ Travers, Peter (25 February 2008). "Oscars 2008: The Live Blog". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ↑ "No. 60895". The London Gazette (Supplement). 14 June 2014. p. b2.

- ↑ "No. 61320". The London Gazette. 11 August 2015. p. 14934.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis knighted by the Duke of Cambridge". The Daily Telegraph. 14 November 2014. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ↑ "Daniel Day-Lewis makes Oscar history with third award". BBC News. 25 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ↑ Clark, Travis (26 April 2021). "The 44 actors who have won multiple Oscars, ranked by who has won the most". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

External links

- Daniel Day-Lewis at IMDb

- Daniel Day-Lewis at the BFI's Screenonline

- Daniel Day-Lewis at Curlie