Elmer Ellsworth Kirkpatrick, Jr. | |

|---|---|

Colonel E. E. Kirkpatrick | |

| Born | 17 August 1905 Yukon, Oklahoma |

| Died | 26 March 1990 (aged 84) Jacksonville, Florida |

| Place of Burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1929–1958 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | World War II: |

| Awards | Legion of Merit (3) Commendation Ribbon |

| Other work | Assistant Professor at University of Florida |

Colonel Elmer Ellsworth Kirkpatrick, Jr., was a United States Army Quartermaster Corps and Army Corps of Engineers officer who worked on the Alaska Highway, the Canol project, and the Manhattan Project during World War II.

A 1929 graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, Kirkpatrick was involved in numerous construction projects in the United States and Panama. He went to Washington, D.C., in October 1940 to work in the office of the Quartermaster General, where he worked to prepare the necessary accommodation and training facilities for the vast army that would be created to fight World War II. After duty in Alaska, he joined the Manhattan Project, and was responsible for the development of the base facilities used for the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

After the war he was chief of staff of the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project, and the head of the Construction Division of the Far East Command in Japan.

Early life

Elmer Ellsworth Kirkpatrick, Jr., was born in Yukon, Oklahoma, on 17 August 1905,[1] the second of four sons of Elmer Ellsworth Kirkpatrick, Sr., a dentist, and his wife Helene Claudia née Spencer. Kirkpatrick and his brothers had a younger sister, Mary Elizabeth.[2]

Kirkpatrick was educated at McKinley Elementary and Central High School in Oklahoma City. He joined the Reserve Officer Training Corps in his freshman year, and rose to the rank of corporal in the 189th Field Artillery Battery of the Oklahoma National Guard. After graduation he spent a year at the Marion Military Institute.[1]

Early career

On 1 July 1925, Kirkpatrick entered the United States Military Academy at West Point,[3] following in the footsteps of his older brother Lewis Spencer Kirkpatrick,[1] who had graduated with the class of 1924.[4] Lewis later died as a prisoner of the Japanese on 27 April 1943.[5] He graduated 169th in his class of 299 on 13 June 1929, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Quartermaster Corps.[3]

Two days later he married Edith Luise Koelsch.[1] His first posting was to Fort Sam Houston, Texas, as an assistant to the Constructing Quartermaster,[3] where his first child, a daughter called Patricia, was born in 1930.[1] On 9 June 1931, he entered Carnegie Institute of Technology,[3] from which he graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in civil engineering the following year.[6]

Kirkpatrick was posted to Hot Springs, Arkansas, in July 1932 as assistant to the Constructing Quartermaster building the Army and Navy Hospital there. He was then sent to Harrodsburg, Kentucky, as assistant to the Constructing Quartermaster in June 1933, where he was engaged in building the Pioneer Memorial Monument there. In November 1933 he returned to West Point as assistant to the Constructing Quartermaster. After five years as a second lieutenant, he was promoted to first lieutenant on 1 November 1934.[6][1]

After attending the Quartermaster School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from September 1936 to June 1937, Kirkpatrick was assigned to Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, as post quartermaster, and then to Fort DuPont, Delaware, as constructing quartermaster in June 1938.[6] His son William Terry was born in Washington, D.C., later that year.[1] He was promoted to captain on 13 June 1939.[6]

Kirkpatrick 's first overseas posting came in August 1939, when he was sent to the Panama Canal Department as assistant constructing quartermaster. There, he supervised works at Fort Davis, Fort Randolph, France Field, and the new anti-aircraft artillery positions on Gatun Lake.[6]

World War II

Kirkpatrick went to Washington, D.C., in October 1940 to work in the office of the Quartermaster General.[7] At this point, the US Army was about to embark on a national mobilization, and it was the task of the Construction Division of the Quartermaster Corps to prepare the necessary accommodation and training facilities for the vast army that would be created to fight World War II, which was already raging in Europe.[8]

The enormous construction program had been dogged by bottlenecks, shortages, delays, spiralling costs, and poor living conditions at the construction sites. Newspapers began publishing accounts charging the Construction Division with incompetence, ineptitude, and inefficiency.[8] Between 1 July 1940 and 10 December 1941, the Construction Division let contracts worth $1,676,293,000.[9] He was promoted to major on 10 October 1942 and lieutenant colonel on 1 February 1942. On 19 February, he was transferred to the Army Corps of Engineers.[7]

In October 1942, Kirkpatrick became district engineer of the Milwaukee District.[7] As such he was responsible for the management of $150 million of construction of airfields, cantonments, and other facilities in Michigan, including a new Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company factory.[1] In March 1943 he became chief of staff of the Northwest Service Command, with its headquarters at Whitehorse, Yukon. This was responsible for the maintenance of the Alaska Highway, and for the Canol project.[1] He was promoted to the rank of colonel on 21 April 1943.[7] For his service, he was awarded the Legion of Merit.[7]

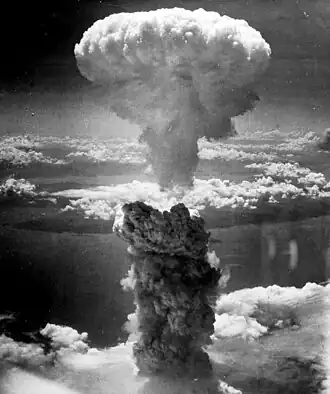

Kirkpatrick returned to Washington, D.C., in September 1944, where he became a special assistant to the director of the Manhattan Project, Major General Leslie R. Groves, Jr. He was sent to the Pacific island of Tinian as liaison to the Twentieth Air Force.[7] On Tinian he was responsible for base development in support of Project Alberta and the 509th Composite Group, and was alternate to Brigadier General Thomas F. Farrell, Groves's deputy for operations. The facilities would be used for operations including the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[10] For his services to the Manhattan Project he was awarded a second Legion of Merit,[11] and the Commendation Ribbon.[7]

Later life

After the war, Kirkpatrick was posted to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, as deputy district engineer of the Manhattan District. He was reduced to his permanent rank of major on 13 June 1946. After the Manhattan District was dissolved he was posted back to West Point in March 1947 as assistant chief of staff, Logistics (G-4). There he was promoted to lieutenant colonel again on 1 July 1948. He returned to Washington, D.C., in July 1949 as chief of staff of the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project.[7]

Kirkpatrick subsequently served in Japan as head of the Construction Division of the Far East Command and United States Army Forces in the Far East, and as Chief of the Japan Construction Agency. He then became district engineer in Jacksonville, Florida, where he was responsible for the construction of the initial facilities at Cape Canaveral for the space program,. This was followed by duty as district engineer of the Southern District of the Mediterranean Division, with its headquarters in Livorno, Italy. He retired from the Army on 1 November 1958 with the rank of colonel.[1] He was awarded a third Legion of Merit.[12]

Kirkpatrick moved to Jacksonville, Florida, where he became an assistant professor in the College of Architecture and the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida. He retired from this in 1965.[1] His son Terry graduated from West Point with the class of 1961 and served with the engineers in the Vietnam War.[12] His wife died in 1982 and he married Virginia Wright in 1986. After he died in Jacksonville on 26 March 1990, he was cremated and half of his ashes were scattered into the waters of Melrose Bay, Florida, while the other half were interred with his first wife's in West Point Cemetery.[1]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Elmer Ellsworth Kirkpatrick, Jr". Kirkpatrick Family Archive. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ↑ "Dr, Elmer E. Kirkpatrick". Kirkpatrick Family Archive. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Cullum 1930, p. 2170.

- ↑ Cullum 1930, p. 1871.

- ↑ Cullum 1950, p. 454.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cullum 1940, p. 808.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cullum 1950, p. 615.

- 1 2 Fine & Remington 1972, pp. 241–243.

- ↑ Fine & Remington 1972, pp. 430–431.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, p. 156.

- ↑ "Valor awards for Elmer E. Kirkpatrick". Military Review. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- 1 2 "Kirkpatrick bio". West Point Association of Graduates. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

References

- Campbell, Richard H. (2005). The Silverplate Bombers: A History and Registry of the Enola Gay and Other B-29s Configured to Carry Atomic Bombs. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-2139-8. OCLC 58554961.

- Cullum, George W. (1930). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume VII 1920–1930. Chicago: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Cullum, George W. (1940). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume VIII 1930–1940. Chicago: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Cullum, George W. (1950). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume IX 1940–1950. Chicago: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Fine, Lenore; Remington, Jesse A. (1972). The Corps of Engineers: Construction in the United States. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 834187.