Official emblem | |

| Institutional overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1977 |

| Jurisdiction | European Union |

| Headquarters | Luxembourg City, Luxembourg 49°37′22″N 6°8′49″E / 49.62278°N 6.14694°E |

| Annual budget | €122,400,938 (2020) |

| Institutional executive |

|

| Website | eca.europa.eu |

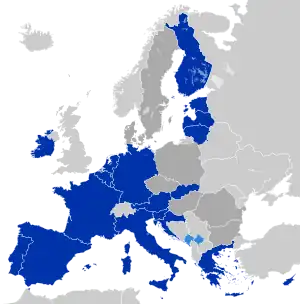

The European Court of Auditors (ECA; French: Cour des comptes européenne) is the supreme audit institution of the European Union (EU). It was established in 1975 in Luxembourg and is one of the seven EU institutions.[1] The Court comprises one member from each EU member state (currently 27) supported by approximately 800 civil servants.

History

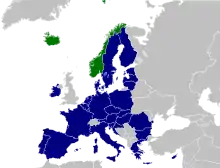

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

The ECA was created by the 1975 Budgetary Treaty and was formally established on 18 October 1977, holding its first session a week later. At that time the ECA was not a formal institution; it was an external body designed to audit the finances of the European Communities. It replaced two separate audit bodies, one which dealt with the finances of the European Economic Community and Euratom, and one which dealt with the European Coal and Steel Community.[2]

The ECA did not have a defined legal status until the Treaty of Maastricht when it was made the fifth institution, the first new institution since the founding of the Community. By becoming an institution it gained some new powers, such as the ability to bring actions before the European Court of Justice (ECJ). At first its audit power related only to the European Community pillar of the European Union (EU), but under the Treaty of Amsterdam it gained the full power to audit the finances of the whole of the EU.[2]

Functions

Despite its name, the ECA has no jurisdictional functions. It is rather a professional external investigatory audit agency.[3] The primary role of the ECA is to externally check if the budget of the European Union has been implemented correctly and that EU funds have been spent legally and with sound management. In doing so, the ECA checks the paperwork of all persons handling any income or expenditure of the Union and carries out spot checks. The ECA is bound to report any problems in its reports for the attention of the EU's Member States and institutions, these reports include its general and specific annual reports, as well as special reports on its performance audits.[4][5] The ECA 's decision is the basis for the European Commission decisions; for example, when the ECA found problems in the management of EU funds in the regions of England, the Commission suspended funds to those regions and is prepared to fine those who do not return to acceptable standards.[6]

In this role, the ECA has to remain independent yet remain in touch with the other institutions; for example, a key role is the presentation of the ECA's annual report to the European Parliament. It is based on this report that the Parliament makes its decision on whether or not to sign off the European Commission's handling of the budget for that year.[4] The Parliament notably refused to do this in 1984 and 1999, the latter case forced the resignation of the Santer Commission.[7] The ECA, if satisfied, also sends assurances to the Council and Parliament that the taxpayers' money is being properly used,[4] and the ECA must be consulted before the adoption of any legislation with financial implications, but its opinion is never binding.[8]

Organisation

The ECA is composed of one member from each EU Member State, each of whom is appointed unanimously by the Council of the European Union for a renewable term of six years.[4] They are not all replaced every six years, however, as their terms do not coincide (four of the original members began with reduced terms of four years for this reason). Members are chosen from people who have served in national audit bodies, who are qualified for the office and whose independence is beyond doubt. While serving in the Court, members cannot engage in any other professional activities.[9]

As the body is independent, its members are free to decide their own organisation and rules of procedure, although these must be ratified by the Council of the European Union.[10] Since the Treaty of Nice, the ECA can set up "chambers" (with only a few Members each) to adopt certain types of reports or opinions.[11]

The ECA is supported by a staff of approximately 800 auditors, translators and administrators recruited as part of the European Civil Service. Auditors are divided into auditor groups which inspect and prepare draft reports for the ECA to take decisions upon. Inspections take place not only of EU institutions but of any state which receives EU funds, given that 90% of income and expenditure is managed by national authorities rather than the EU. Upon finding a fault, the ECA—possessing no legal powers of its own—informs the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF), which is the EU's anti-fraud agency.[4] The ECA is also assisted by the Secretary-General of the European Court of Auditors, elected by the College of ECA Members, who—along with general management and assistance to the President—draws up draft minutes and keeps archives of decisions, as well as ensuring the publication of reports in the Official Journal of the European Union.[12]

President

The members then elect one of their members as the President of the ECA for a renewable three-year term. The election takes place by a secret ballot of those members who applied for the presidency. The duties of the President (which may be delegated) are to convene and chair the meetings of the ECA, ensuring that decisions are implemented and the departments (and other activities) are soundly managed. The President also represents the institution and appoints a representative for it in contentious proceedings.[12]

The current President is Tony Murphy (from Ireland) who took office on October 1, 2022. He succeeded Klaus-Heiner Lehne (Germany), elected in 2016. The previous presidents were Sir Norman Price (elected in 1977, United Kingdom), Michael Murphy (1977, Ireland), Pierre Lelong (1981, France), Marcel Mart (1984, Luxembourg), Aldo Angioi (1990, Italy), André Middelhoek (1992, Netherlands), Bernhard Friedmann (1996, Germany), Jan O. Karlsson (1999, Sweden), Juan Manuel Fabra Vallés † (2002, Spain), Hubert Weber (2006, Austria), and Vítor Manuel da Silva Caldeira (2007, Portugal).[13]

Secretary-general

The Secretary-General is the ECA's most senior member of staff. Appointed for a renewable term of 6 years, he is responsible for the management of the ECA's staff and for the administration of the ECA. In addition, the Secretary-General is responsible for the budget, translation, training and information technology.

List of secretaries-general

- 1989–1994: Patrick Everard

- 1994–2001: Edouard Ruppert

- 2001–2008: Michel Hervé (France)

- 2008–2009: John Speed (ad interim, United Kingdom)

- 2009–2020: Eduardo Ruiz Garcia (Spain)

- 2020–2020: Philippe Froidure (ad interim)

- Since 2021: Zacharias Kolias (Greece)

Staffing

ECA staff are mainly officials recruited via the reserve lists from general competitions organised by the European Personnel Selection Office external link (EPSO). In certain circumstances, however, the ECA may also engage temporary or contract staff. To be eligible for a post at the ECA, one must be a citizen of one of the European Union Member States.

Traineeships

Just like the other EU institutions, the ECA organises three traineeship sessions per year in areas of interest to its work. Traineeships are granted for three, four or five months maximum, and may be remunerated (€1500 /month) or non-remunerated.

Work

The ECA publishes the results of its audit work in a variety of reports – annual reports, specific annual reports and special reports – depending on the type of audit. Other published products include opinions and review-based publications. In total, the ECA published 93 reports in 2017. All reports, opinions and reviews are published on the ECA's website in the official EU languages.

Criticism

Statement of assurance

Since 1994 the ECA has been required to provide a "statement of assurance", essentially a certificate that an entire annual budget can be accounted for. This has proved to be a problem, as even relatively minor omissions require the ECA to refuse a statement of assurance for the entire budget, even if almost all of the budget is considered reliable.

This has led to media reports of the EU accounts being "riddled with fraud", where issues are based on errors in paperwork even though the underlying spending was legal. The auditing system itself has drawn criticism from this perception. The Commission in particular has stated that the bar is too high, and that only 0.09% of the budget is subject to fraud.[14] The Commission has elsewhere stated that it is important to distinguish between fraud and other irregularities.[15] The controversial dismissal in 2003 of Marta Andreasen for her criticism of procedures in 2002 has, for some, called into doubt the integrity of the institutions.

It is frequently claimed that annual accounts have not been certified by the external auditor since 1994. In its annual report on the implementation of the 2009 EU Budget, the Court of Auditors found that the two biggest areas of the EU budget, agriculture and regional spending, have not been signed off on and remain "materially affected by error".[16] Nonetheless, the European Commission claims that every budget since 2007 has been signed off.[17]

Terry Wynn, an MEP who served on the Parliament's Committee on Budgetary Control and reached the position of chairman, has also backed these calls, stating that it is impossible for the Commission to achieve these standards. In a report entitled EU Budget – Public Perception & Fact – how much does it cost, where does the money go and why is it criticised so much?, Wynn cites consensus that practice in the EU differs from that in the US. In the US, the focus is on the financial information, not on the legality and regularity of the underlying transactions, 'So, other than in Europe, the political reaction in the US to the failure to obtain a clean audit opinion is only "a big yawn"'.[18]

By comparison, the Comptroller and Auditor General for the United Kingdom stated that there were 500 separate accounts for the UK, and "in the last year, I qualified 13 of the 500. If I had to operate the EU system, then, because I qualify 13 accounts, I might have to qualify the whole British central government expenditure". Despite the problems, the Barroso Commission stated that it aimed to bring the budget within the Court's limits by the end of its mandate in 2009.[14]

The ECA made clear in its year report for 2010 that "Responsibility for the legality and regularity of spending on Cohesion Policies starts in the Member States, but the Commission bears the ultimate responsibility for the correct implementation of the budget". In previous reports, the ECA has noted that "Regardless of the method of implementation applied, the Commission bears the ultimate responsibility for the legality and regularity of the transactions underlying the accounts of the European Communities (Article 274 of the Treaty)".[16]

Size

The size of the ECA has also come under criticism. Owing to the one-member-per-state system, its College of Members grew from nine to twenty-eight as of 2013. Attempting to get consensus in the body has thus become more difficult; this led to the number of its special reports per year shrinking from fifteen to six between 2003 and 2005, despite its staff growing by 200 over the same period. Some proposals have been for its size to be reduced to five members or just one, possibly with an advisory board with members from each member state. However, neither the European Constitution nor the Treaty of Lisbon proposed any changes to its composition, despite calls by former ECA members and MEPs to embrace change.[3][19]

Legislative references

See also

- Secretary-General of the European Court of Auditors

- Cour des Comptes (France)

- Federal Court of Auditors of Germany

- Tribunal de Cuentas (Spain)

- Chamber of Accounts (Greece)

- Swedish National Audit Office

- Government Accountability Office (US)

- Australian National Audit Office

- National Audit Office (China)

- Bundesrechnungshof

- National Audit Office (United Kingdom)

- Supreme Chamber of Control of the Republic of Poland

- Netherlands Court of Audit

- Court of Audit of Belgium

- Rigsrevisionen

References

- ↑ "Glossary of summaries – EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 6 January 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- 1 2 "European Court of Auditors". CVCE. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- 1 2 Bösch, Herbert (18 October 2007). "Speech by Herbert Bösch, Chairman of the European Parliament's Committee on Budgetary Control". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Institutions of the EU: The European Court of Auditors". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 22 December 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ↑ "Power of audit of the European Court of Auditors". CVCE. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ "EU may force region to repay cash". BBC News. 16 October 2007. Archived from the original on 19 October 2007. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- ↑ "Budgetary control: 1996 discharge raises issue of confidence in the Commission". Europa (web portal). 1999. Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ↑ "Consultative powers of the European Court of Auditors". CVCE. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ "Composition of the European Court of Auditors". CVCE. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ "Organisation and operation of the European Court of Auditors". CVCE. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ "Glossary: The European Court of Auditors". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 16 January 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- 1 2 "Organisation of the European Court of Auditors". CVCE. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ "Presidents of the European Court of Auditors". CVCE. 13 August 2011. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- 1 2 Mulvey, Stephen (24 October 2006). "Why the EU's audit is bad news". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ↑ "Protection of the European Union's financial interests – Fight against fraud – Annual Report 2009 (vid. p. 5)" (PDF). Europa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- 1 2 "OpenEurope". OpenEurope. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ "Fact check on the EU budget | European Commission". Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ↑ "EU Budget – Public Perception & Fact (vid. II.1.2; Conclusion)". Terry Wynn. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ↑ Karlsson, Jan; Tobisson, Lars (6 June 2007). "'Much talk, little action' at European Court of Auditors". European Voice. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

External links

- Archives of the European Court of Auditors at the Historical Archives of the EU in Florence

- Access to documents of the Court of Auditors on EUR-Lex

- European Court of Auditors page on CVCE.eu