| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(2S)-3′,5-Dihydroxy-4′-methoxy-7-[α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranosyloxy]flavan-4-one | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(22S,42S,43R,44S,45S,46R,72R,73R,74R,75R,76S)-13,25,43,44,45,73,74,75-Octahydroxy-14-methoxy-76-methyl-22,23-dihydro-24H-3,6-dioxa-2(2,7)-[1]benzopyrana-4(2,6),7(2)-bis(oxana)-1(1)-benzenaheptaphan-24-one | |

| Other names

Hesperetin, 7-rutinoside,[1] Cirantin, hesperidoside|heperetin, 7-rhamnoglucoside, hesperitin, 7-O-rutinoside | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.536 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C28H34O15 | |

| Molar mass | 610.565 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.65 ± 0.1g/mL (predicted) |

| Melting point | 262 °C |

| Boiling point | 930.1 ± 65 °C (predicted) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Hesperidin is a flavanone glycoside found in citrus fruits. Its aglycone is hesperetin. Its name is derived from the word "hesperidium", for fruit produced by citrus trees.

Hesperidin was first isolated in 1828 by French chemist M. Lebreton from the white inner layer of citrus peels (mesocarp, albedo).[2][3]

Hesperidin is believed to play a role in plant defense.

Sources

Rutaceae

- 700–2,500 ppm in fruit of Citrus aurantium (bitter orange, petitgrain)[4]

- in orange juice (Citrus sinensis)

- in Zanthoxylum gilletii[5]

- in lemon[6]

- in lime[6]

- in leaves of Agathosma serratifolia

Lamiaceae

Peppermint contains hesperidin.[7]

Content in foods

Approximate hesperidin content per 100 ml or 100 g[8]

- 481 mg peppermint, dried

- 44 mg blood orange, pure juice

- 26 mg orange, pure juice

- 18 mg lemon, pure juice

- 14 mg lime, pure juice

- 1 mg grapefruit, pure juice

Metabolism

Hesperidin 6-O-α-L-rhamnosyl-β-D-glucosidase, an enzyme that uses hesperidin and water to produce hesperetin and rutinose, is found in the Ascomycetes species.[9]

Research

As a flavanone found in the rinds of citrus fruits (such as oranges or lemons), hesperidin is under preliminary research for its possible biological properties in vivo. One review did not find evidence that hesperidin affected blood lipid levels or hypertension.[10] Another review found that hesperidin may improve endothelial function in humans, but the overall results were inconclusive.[11]

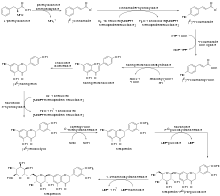

Biosynthesis

The biosynthesis of hesperidin stems from the phenylpropanoid pathway, in which the natural amino acid L-phenylalanine undergoes a deamination by phenylalanine ammonia lyase to afford (E)-cinnamate.[12] The resulting monocarboxylate undergoes an oxidation by cinnamate 4-hydroxylase to afford (E)-4-coumarate,[13] which is transformed into (E)-4-coumaroyl-CoA by 4-coumarate-CoA ligase.[14] (E)-4-coumaroyl-CoA is then subjected to the type III polyketide synthase naringenin chalcone synthase, undergoing successive condensation reactions and ultimately a ring-closing Claisen condensation to afford naringenin chalcone.[15] The corresponding chalcone undergoes an isomerization by chalcone isomerase to afford (2S)-naringenin,[16] which is oxidized to (2S)-eriodictyol by flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase.[17] After O-methylation by caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase,[18] the hesperitin product undergoes a glycosylation by flavanone 7-O-glucosyltransferase to afford hesperitin-7-O-β-D-glucoside.[19] Finally, a rhamnosyl moiety is introduced to the monoglycosylated product by 1,2-rhamnosyltransferase, forming hesperidin.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Dakshini KM (August 1991). "Hesperetin 7-rutinoside (hesperidin) and taxifolin 3-arabinoside as germination and growth inhibitors in soils associated with the weed, Pluchea lanceolata (DC) C.B. Clarke (Asteraceae)". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 17 (8): 1585–1591. doi:10.1007/BF00984690. PMID 24257882. S2CID 35483504.

- ↑ Lebreton, M (1828). "Sur la matière cristalline des orangettes, et analyse de ces fruits non encore developpés, famille des Hesperidées". Journal de Pharmacie et de Sciences Accessories. 14: 377. Archived from the original on 2020-10-20. Retrieved 2016-10-30.

- ↑ "Metabocard for Hesperidin (HMDB03265)". Human Metabolome Database, The Metabolomics Innovation Centre, Genome Canada. 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 30 October 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ↑ "Citrus aurantium L." Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases. 6 Oct 2014. Archived from the original on 2004-11-10.

- ↑ Tringali C, Spatafora C, Calì V, Simmonds MS (June 2001). "Antifeedant constituents from Fagara macrophylla". Fitoterapia. 72 (5): 538–543. doi:10.1016/S0367-326X(01)00265-9. PMID 11429249.

- 1 2 Peterson JJ, Beecher GR, Bhagwat SA, Dwyer JT, Gebhardt SE, Haytowitz DB, Holden JM (2006). "Flavanones in grapefruit, lemons, and limes: A compilation and review of the data from the analytical literature" (PDF). Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 19 (Supplement): S74–S80. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2005.12.009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-04-02. Retrieved 2014-01-24.

- ↑ Dolzhenko Y, Bertea CM, Occhipinti A, Bossi S, Maffei ME (August 2010). "UV-B modulates the interplay between terpenoids and flavonoids in peppermint (Mentha × piperita L.)". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 100 (2): 67–75. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2010.05.003. hdl:2318/77560. PMID 20627615.

- ↑ "Foods in which hesperidin is found". Phenol-Explorer database, version 3.6. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ↑ Mazzaferro L, Piñuel L, Minig M, Breccia JD (May 2010). "Extracellular monoenzyme deglycosylation system of 7-O-linked flavonoid beta-rutinosides and its disaccharide transglycosylation activity from Stilbella fimetaria". Archives of Microbiology. 192 (5): 383–393. doi:10.1007/s00203-010-0567-7. hdl:11336/81705. PMID 20358178. S2CID 25979489.

- ↑ Mohammadi M, Ramezani-Jolfaie N, Lorzadeh E, Khoshbakht Y, Salehi-Abargouei A (March 2019). "Hesperidin, a major flavonoid in orange juice, might not affect lipid profile and blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials". Phytotherapy Research. 33 (3): 534–545. doi:10.1002/ptr.6264. PMID 30632207. S2CID 58564512.

- ↑ Pla-Pagà L, Companys J, Calderón-Pérez L, Llauradó E, Solà R, Valls RM, Pedret A (December 2019). "Effects of hesperidin consumption on cardiovascular risk biomarkers: a systematic review of animal studies and human randomized clinical trials". Nutrition Reviews. 77 (12): 845–864. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuz036. PMID 31271436.

- ↑ Wanner LA, Li G, Ware D, Somssich IE, Davis KR (January 1995). "The phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana". Plant Molecular Biology. 27 (2): 327–338. doi:10.1007/BF00020187. PMID 7888622. S2CID 25919229.

- ↑ Mizutani M, Ohta D, Sato R (March 1997). "Isolation of a cDNA and a genomic clone encoding cinnamate 4-hydroxylase from Arabidopsis and its expression manner in planta". Plant Physiology. 113 (3): 755–763. doi:10.1104/pp.113.3.755. PMC 158193. PMID 9085571.

- ↑ Costa MA, Bedgar DL, Moinuddin SG, Kim KW, Cardenas CL, Cochrane FC, et al. (September 2005). "Characterization in vitro and in vivo of the putative multigene 4-coumarate:CoA ligase network in Arabidopsis: syringyl lignin and sinapate/sinapyl alcohol derivative formation". Phytochemistry. 66 (17): 2072–2091. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.06.022. PMID 16099486.

- ↑ Leyva A, Jarillo JA, Salinas J, Martinez-Zapater JM (May 1995). "Low Temperature Induces the Accumulation of Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase and Chalcone Synthase mRNAs of Arabidopsis thaliana in a Light-Dependent Manner". Plant Physiology. 108 (1): 39–46. doi:10.1104/pp.108.1.39. PMC 157303. PMID 12228452.

- ↑ Jez JM, Noel JP (January 2002). "Reaction mechanism of chalcone isomerase. pH dependence, diffusion control, and product binding differences". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (2): 1361–1369. doi:10.1074/jbc.m109224200. PMID 11698411.

- ↑ Schoenbohm C, Martens S, Eder C, Forkmann G, Weisshaar B (August 2000). "Identification of the Arabidopsis thaliana flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase gene and functional expression of the encoded P450 enzyme". Biological Chemistry. 381 (8): 749–753. doi:10.1515/BC.2000.095. PMID 11030432. S2CID 22010146.

- ↑ Lin Y, Sun X, Yuan Q, Yan Y (July 2013). "Combinatorial biosynthesis of plant-specific coumarins in bacteria". Metabolic Engineering. 18: 69–77. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2013.04.004. PMID 23644174.

- ↑ Durren RL, McIntosh CA (November 1999). "Flavanone-7-O-glucosyltransferase activity from Petunia hybrida". Phytochemistry. 52 (5): 793–798. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00307-6. PMID 10626374.

- ↑ Bar-Peled M, Lewinsohn E, Fluhr R, Gressel J (November 1991). "UDP-rhamnose:flavanone-7-O-glucoside-2″-O-rhamnosyltransferase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 266 (31): 20953–20959. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)54803-1. PMID 1939145.

External links

Media related to Hesperidin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hesperidin at Wikimedia Commons