| History of Malaysia |

|---|

|

|

|

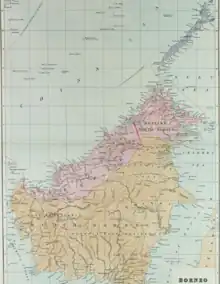

The History of Sarawak can be traced as far as 40,000 years ago to the paleolithic period where the earliest evidence of human settlement is found in the Niah caves. A series of Chinese ceramics dated from the 8th to 13th century AD was uncovered at the archeological site of Santubong. The coastal regions of Sarawak came under the influence of the Bruneian Empire in the 16th century. In 1839, James Brooke, a British explorer, first arrived in Sarawak. Sarawak was later governed by the Brooke family between 1841 and 1946. During World War II, it was occupied by the Japanese for three years. After the war, the last White Rajah, Charles Vyner Brooke, ceded Sarawak to Britain, and in 1946 it became a British Crown Colony. On 22 July 1963, Sarawak was granted self-government by the British. Following this, it became one of the founding members of the Federation of Malaysia, established on 16 September 1963. However, the federation was opposed by Indonesia, and this led to the three-year Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation. From 1960 to 1990, Sarawak experienced a communist insurgency.

Prehistory

The first foragers visited the West Mouth of the Niah Caves (located 110 kilometres (68 mi) southwest of Miri)[1] 65,000 years ago instead of 40,000 years ago as previously believed, when Borneo was connected to the mainland of Southeast Asia.[2] The landscape around the Niah Caves was drier and more exposed than it is now. Prehistorically, the Niah Caves were surrounded by a combination of closed forests with bush, parkland, swamps, and rivers. The foragers were able to survive in the rainforest through hunting, fishing, and gathering molluscs and edible plants.[3] This new timeline of 65,000 years was established when five pieces of microlithic tools that were aged 65,000 years old and a human skull that was aged 55,000 years were discovered at part of the Niah Caves complex, Trader cave, during excavation work.[4] An earlier evidence is the discovery of a modern human skull, nicknamed "Deep Skull", in a deep trench uncovered by Barbara and Tom Harrisson (a British ethnologist) in 1958;[1][5] this is also the oldest modern human skull in Southeast Asia.[6] The Deep Skull probably belongs to a 16- to 17-year-old adolescent girl.[3] When compared with the Iban skull and other fossils, the Deep Skull most closely resembles the indigenous people of Borneo today, with their delicate features and small body size, and it has few similarities with the skulls of the indigenous Australians.[7] Mesolithic and Neolithic burial sites have also been found.[8] The area around the Niah Caves has been designated the Niah National Park.[9]

Another earlier excavation by Tom Harrisson in 1949 unearthed a series of Chinese ceramics at Santubong (near Kuching) that date to the Tang and the Song dynasties in the 8th to 19th century AD. It is possible that Santubong was an important seaport in Sarawak during the period, but its importance declined during the Yuan dynasty, and the port was deserted during the Ming dynasty.[10] Other archaeological sites in Sarawak can be found inside the Kapit, Song, Serian, and Bau districts.[11]

Malano kingdoms

The Melano kingdom existed from about 1300 to 1400 AD and centred at the Mukah river. Rajah Tugau is the most renowned King in Sarawak as of now. His kingdom consisted of groups of similar Melanau and Kajang language speakers and covered coastal Sarawak until Belait. They also share almost identical culture and heritage. According to the manuscript of Brunei's rulers, following the fall of Majapahit, Barunai led by Awang Semaun being reinforced by the Iban, conquered Tutong under its chief Mawanga and the whole of the Melano kingdom until Igan under its chief Basiung despite reinforcement from Sambas. Barunai continued the conquest of the entire south and then north of Borneo Island, after which conquered the whole Sulu and Philippines.[12] Nagarakertagama, written in 1365 during Hayam Wuruk, mentions Malano and Barune(ng) among the 14 tributaries of Majapahit. After the fall of Majapahit, Barune(ng) expanded its territory along the northern coast of Borneo island. The Catalan Atlas published in 1375 shows the map of the Malano kingdom. This was confirmed by a Portuguese map which shows the existence of a polity called Malano. At Florence, Italy, an old map dated 1595 shows the Sarawak coastal areas as districts of Oya, Balingian dan Mukah which was marked as Malano. In the Nan-hai-chih of China mentioned Achen atau Igan. According to Historian Robert Nicholl, Rajah Tugau of the Melanao was the Rajah Makatunao mentioned in the Philippine History book of Maragtas to which the 10 Datus of the Kedatuan of Madja-as in Panay Island, waged a war against, it is through the Melano that Visayans have further links with the Srivijayans in Vijayapura (The Srivijayan vassal-state in Borneo) before the conquest of Majapahit.[13]

Other Malay kingdoms within the Sarawak were Santubong (near Kuching), Sadong (near Samarahan), Saribas, Kalaka (both in Betong Division), Banting and Lingga (both located in Sri Aman).[14][15]

Bruneian Empire and the Sultanate of Sarawak

During the 16th century, the Kuching area was known to Portuguese cartographers as Cerava, one of the five great seaports on the island of Borneo.[16][17] During its golden age, Brunei under Nahkhod Raga Sultan Bolkiah (1473-1521 AD) managed to conquer the Santubong Kingdom in 1512. For a short period of time, it was self-governed under the Sultan of Brunei's younger brother, Sultan Tengah in 1599.[18] The new Sultan's younger brother, Pengiran Muda Tengah, also wanted to become Sultan of Brunei by claiming himself rightful successor on the basis of having been born when his father became the Crown Prince. Sultan Abdul Jalilul Akbar responded by proclaiming Pengiran Muda Tengah as Sultan of Sarawak, as at that time Sarawak was a territory administered by Brunei. Sultan Tengah was killed at Batu Buaya in 1641 by one of his followers. He was buried in Kampong Batu Buaya. With his death, the Sultanate of Sarawak came to an end and later consolidated into Brunei once more. By the early 19th century, Sarawak had become a loosely governed territory under the control of the Brunei Sultanate. The Bruneian Empire had authority only along the coastal regions of Sarawak held by semi-independent Malay leaders. Meanwhile, the interior of Sarawak suffered from tribal wars fought by Iban, Kayan, and Kenyah peoples, who aggressively fought to expand their territories.[19]

Following the discovery of antimony ore in the Kuching region, Pangeran Indera Mahkota (a representative of the Sultan of Brunei) began to develop the territory between 1824 and 1830. When antimony production increased, the Brunei Sultanate demanded higher taxes from Sarawak; this led to civil unrest and chaos.[20] In 1839, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II (1827–1852), ordered his uncle Pengiran Muda Hashim to restore order. Pangeran Muda Hashim requested the assistance of British sailor James Brooke in the matter, but Brooke refused.[21] However, in 1841 during his next visit to Sarawak in 1841 he agreed to a repeated request. Pangeran Muda Hashim signed a treaty in 1841 surrendering Sarawak to Brooke. On 24 September 1841,[22] Pangeran Muda Hashim bestowed the title of governor on James Brooke. This appointment was later confirmed by the Sultan of Brunei in 1842. In 1843, James Brooke decided to create a pro-British Brunei government by installing Pangeran Muda Hashim into the Brunei Court as he would take Brooke's advice, forcing Brunei to appoint Hashim under the guns of East India Company's steamer Phlegethon. The Brunei Court was unhappy with Hashim's appointment and had him assassinated in 1845. In retaliation, James Brooke attacked Kampong Ayer, the capital of Brunei. After the incident, the Sultan of Brunei sent an apology letter to Queen Victoria. The sultan also confirmed James Brooke's possession of Sarawak and his mining rights of antimony without paying tribute to Brunei.[23] In 1846 Brooke effectively became the Rajah of Sarawak and founded the White Rajah Dynasty of Sarawak.[24][25]

The Iban expansion to Sarawak

Based on the Iban legends and myths, they originally arrived from the Kapuas river in West Kalimantan (in present-day Indonesian Borneo). The early migrations to Sarawak was a result of the tribal issues in their Kapuas Hulu ancestral homeland.[26][27][28] The early Iban folk story was also aligned by the modern-day language research by Asmah Haji Omar (1981), Rahim Aman (1997), Chong Shin and James T. Collins (2019) as well as from the evidence of material cultures from M. Heppell (2020) that verify the Iban language and its cultures emerged from the upper Kapuas region.[29]

According to the studies made by Benedict Sandin (1968), the era of Iban migrations from Kapuas Hulu was identified to begin from 1750s onwards.[29] The pioneers were described to arrived in Batang Lupar and founded a settlement near the Undop River. Within five generations, the Ibans of Batang Lupar spreaded to the north, east and west, establishing new communities situated the boundaries of Batang Lupar, Batang Sadong, Saribas and Batang Layar.

During the White Rajah's era in the 19th century, the migrations of the Ibans largely headed north towards the Rejang Basin, the area was reach from the upper Katibas, Batang Lupar and Saribas Rivers. A large community of Iban was recorded near Mukah and Oya river by 1870s. By the early 20th century, the Iban pioneers arrived in Tatau, Kemena (Bintulu) and Balingan. In 1900s, the Iban has expanded to the Baram valley and Limbang River northern Sarawak.

The colonial documents during the Brooke's administration has recorded several complications pertaining to the migration of the Ibans, as the Iban community can effortlessly outnumbered the original pre-existing tribes, as well as created an adverse environmental mark on the lands originally intended for swidden agriculture. Hence, the Ibans were barred from the government to migrate to other river system. The strain between the Iban people against the Brooke administraive policies were reported in the Balleh Valley.[29]

In spite of the challengers between the Brooke's administration and the settlers during the early migration period, the migration has created a good oppurtunity for both parties. The Ibans, known for their extensive skills and knowledge on the forest and lands were approved to seek new lands to explore forst produce including camphor, rattans, wild rubber and damar. The colonial government then approved permenant Iban settlements across the newly acquired territories of Sarawak. For instance, in the 1890 cessesion of Limbang, the Ibans were entrusted by the government to settle in the area. A correlating program can also be seen in Baram.[29]

Towards the end of the 19th century, there are several areas in Sarawak that recorded overpopulation, including Batang Lupar, Skrang Valley and Batang Ai. Thus, the Sarawakian govenmernment initiated a program to open up several territories for the Iban settlements, with several conditions. This can be seen on the unlimited migrations of Ibans heading to Baram, Balingan and Bintulu. A similar process can also be witnessed in the early 1900s, where the Ibans in the Second Division were permitted to settle in Limbang, as well as the migrations of the Ibans to Batang Lupar from Lundu.[29]

The colonial government initiative has left a favourable effect on the expansion of the Iban language and culture throughout modern day Sarawak. At the same time, the mass migration has equally impacted other indigenous groups, for instance amongst the Bukitans in Batang Lupar, an intensive intermarriage by the Bukitan leaders resulted the Batang Lupar Bukitan populations assimilate in the Iban society. However, there are other groups that resulted in a fiercer relationship, for example the Ukits, Seru, Miriek and Biliun in which their traditional communities were almost replaced the Ibans.[30]

Brooke dynasty

_by_Francis_Grant.jpg.webp)

James Brooke ruled the area and expanded the territory northwards until his death in 1868. He was succeeded by his nephew Charles Anthoni Johnson Brooke, who in turn was succeeded by his son, Charles Vyner Brooke, on the condition that Charles Anthoni should rule in consultation with Vyner Brooke's brother Bertram Brooke.[31] Both James and Charles Anthoni Johnson Brooke pressured Brunei to sign treaties as a strategy to acquire territories from Brunei and expand the territorial boundaries of Sarawak. In 1861, Brunei ceded the Bintulu region to James Brooke. Sarawak was recognised as an independent state by the United States in 1850 and the United Kingdom in 1864. The state issued its first currency as the Sarawak dollar in 1858.[32] In 1883 Sarawak was extended to the Baram River (near Miri). Limbang was added to Sarawak in 1890. The final expansion of Sarawak occurred in 1905 when Lawas was ceded to the Brooke government.[33][34] Sarawak was divided into five divisions, corresponding to territorial boundaries of the areas acquired by the Brookes through the years. Each division was headed by a Resident.[35]

Sarawak became a British protectorate in 1888, while still ruled by the Brooke dynasty. The Brookes ruled Sarawak for a hundred years as "White Rajahs".[36] The Brookes adopted a policy of paternalism to protect the interests of the indigenous population and their overall welfare. While the Brooke government established a Supreme Council consisting of Malay chiefs who advised the Rajahs on all aspects of governance,[37] in the Malaysian context the Brooke family is viewed as a colonialist.[38] The Supreme Council is the oldest state legislative assembly in Malaysia, with the first General Council meeting taking place at Bintulu in 1867.[39] Meanwhile, the Ibans and other Dayak people were hired as militia.[40] The Brooke dynasty encouraged the immigration of Chinese merchants for economic development, especially in the mining and agricultural sectors.[37][41] Western businessmen were restricted from entering the state while Christian missionaries were tolerated.[37] Piracy, slavery, and headhunting were banned.[42] Borneo Company Limited was formed in 1856. It was involved in a wide range of businesses in Sarawak such as trade, banking, agriculture, mineral exploration, and development.[43]

In 1857, 500 Hakka Chinese gold miners from Bau, under the leadership of Liu Shan Bang, destroyed the Brookes' house. Brooke escaped and organised a bigger army together with his nephew Charles[44] and his Malayo-Iban supporters.[37] A few days later, Brooke's army was able to cut off the escape route of the Chinese rebels, who were defeated after two months of fighting.[45][41] The Brookes subsequently built a new government house by the Sarawak River at Kuching.[46][47] An anti-Brooke faction at the Brunei Court was defeated in 1860 at Mukah. Other notable rebellions that were successfully quashed by the Brookes include those led by an Iban leader Rentap (1853–1863), and a Malay leader named Syarif Masahor (1860–1862).[37] As a result, a series of forts were built around Kuching to consolidate the Rajah's power. These include Fort Margherita, which was completed in 1879.[47] In 1891 Charles Anthoni Brooke established the Sarawak Museum, the oldest museum in Borneo.[47][48] In 1899, Charles Anthoni Brooke ended the intertribal wars in Marudi. The first oil well was drilled in 1910. Two years later, the Brooke Dockyard opened. Anthony Brooke was born in the same year and became Rajah Muda in 1939.[49]

In 1941, during the centenary celebration of Brooke rule in Sarawak, a new constitution was introduced to limit the power of the Rajah and to allow the Sarawak people to play a greater role in the functioning of the government.[50] However, the draft included a secret agreement drawn up between Charles Vyner Brooke and British government officials, in which Vyner Brooke ceded Sarawak as a British Crown Colony in return for a financial compensation to him and his family.

Japanese occupation and Allied liberation

The Brooke government, under the leadership of Charles Vyner Brooke, established several airstrips in Kuching, Oya, Mukah, Bintulu, and Miri for preparations in the event of war. By 1941, the British had withdrawn its defending forces from Sarawak to Singapore. With Sarawak now unguarded, the Brooke regime decided to adopt a scorched earth policy where oil installations in Miri would be destroyed and the Kuching airfield will be held as long as possible before being destroyed. Meanwhile, Japanese forces seized British Borneo to guard their eastern flank in the Malayan Campaign and to facilitate their invasion of Sumatra and West Java. A Japanese invasion force led by Kiyotake Kawaguchi landed in Miri on 16 December 1941 (eight days into the Malayan Campaign) and conquered Kuching on 24 December 1941. British forces led by Lieutenant Colonel C. M. Lane retreated to Singkawang in Dutch Borneo bordering Sarawak. After ten weeks of fighting in Dutch Borneo, the Allied forces surrendered on 1 April 1942.[51] When the Japanese invaded Sarawak, Charles Vyner Brooke had already left for Sydney, Australia, while his officers were captured by the Japanese and interned at the Batu Lintang camp.[52]

Sarawak remained part of the Empire of Japan for three years and eight months. Sarawak, together with North Borneo and Brunei, formed a single administrative unit named Kita Boruneo (Northern Borneo)[53] under the Japanese 37th Army headquartered in Kuching. Sarawak was divided into three provinces, namely: Kuching-shu, Sibu-shu, and Miri-shu, each under their respective Japanese Provincial Governor. The Japanese retained pre-war administrative machinery and assigned Japanese for government positions. The administration of Sarawak's interior was left to the native police and village headmen, under Japanese supervision. Though the Malays were typically receptive toward the Japanese, other indigenous tribes such as the Iban, Kayan, Kenyah, Kelabit and Lun Bawang maintained a hostile attitude toward them because of policies such as compulsory labour, forced deliveries of foodstuffs, and confiscation of firearms. The Japanese did not resort to strong measures in clamping down on the Chinese population because the Chinese in the state were generally apolitical. However, a considerable number of Chinese moved from urban areas into the less accessible interior to lessen contact with the Japanese.[54]

Allied forces later formed the Z Special Unit to sabotage Japanese operations in Southeast Asia. Beginning in March 1945, Allied commanders were parachuted into Borneo jungles and established several bases in Sarawak under an operation codenamed "Semut". Hundreds of indigenous people were trained to launch offensives against the Japanese.[55] During the battle of North Borneo, the Australian forces landed at Lutong-Miri area on 20 June 1945 and had penetrated as far as Marudi and Limbang before halting their operations in Sarawak.[56] After the surrender of Japan, the Japanese surrendered to the Australian forces at Labuan on 10 September 1945.[57][58] This was followed by the official surrender ceremony at Kuching aboard the Australian Corvette HMAS Kapunda on 11 September 1945.[59] The Batu Lintang camp was liberated on the same day.[60] Sarawak was immediately placed under British Military Administration until April 1946.[61]

A map of the occupation of Borneo in 1943 prepared by the Japanese during World War II, with label written in Japanese characters.

A map of the occupation of Borneo in 1943 prepared by the Japanese during World War II, with label written in Japanese characters. Large crowd of Sarawak native population throngs the street of Kuching to witness the arrival of Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on 12 September 1945.

Large crowd of Sarawak native population throngs the street of Kuching to witness the arrival of Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on 12 September 1945. The official surrender ceremony of the Japanese to the Australian forces at Kuching on 11 September 1945.

The official surrender ceremony of the Japanese to the Australian forces at Kuching on 11 September 1945. A large world map, showing the Japanese-occupied area in Asia, set up in the main street of Sarawak's capital.

A large world map, showing the Japanese-occupied area in Asia, set up in the main street of Sarawak's capital.

British crown colony

After the war, the Brooke government did not have enough resources to rebuild Sarawak. Charles Vyner Brooke was also not willing to hand over his power to his heir apparent, Anthony Brooke (his nephew, the only son of Bertram Brooke) because of serious differences between them.[19][note 1] Furthermore, Vyner Brooke's wife, Sylvia Brett, tried to defame Anthony Brooke in order to install her daughter to the throne. Faced with these problems, Vyner Brooke decided to cede sovereignty of Sarawak to the British Crown. A Cession Bill was put forth in the Council Negri (now Sarawak State Legislative Assembly) and was debated for three days. The bill was passed on 17 May 1946 with a narrow majority (19 versus 16 votes). Supporters of the bill were mostly European officers, while the Malays opposed the bill. This caused hundreds of Malay civil servants to resign in protest, sparking an anti-cession movement and the assassination of the second colonial governor of Sarawak Sir Duncan Stewart by Rosli Dhobi.[62]

Anthony Brooke opposed the cession of Sarawak to the British Crown, and was linked to anti-cessionist groups in Sarawak, especially after the assassination of Sir Duncan Stewart.[63] Anthony Brooke continued to claim sovereignty as Rajah of Sarawak even after Sarawak became a British Crown colony on 1 July 1946. For this he was banished from Sarawak by the colonial government[37][note 2] and was allowed to return only 17 years later for a nostalgic visit, when Sarawak became part of Malaysia.[64] In 1950 all anti-cession movements in Sarawak ceased after a clamp-down by the colonial government.[19] In 1951 Anthony relinquished all his claims to the Sarawak throne after he used up his last legal avenue at the Privy Council.[64]

Self-government and the Federation of Malaysia

.jpg.webp)

On 27 May 1961, Tunku Abdul Rahman, the prime minister of the Federation of Malaya, announced a plan to form a greater federation together with Singapore, Sarawak, Sabah and Brunei, to be called Malaysia. This plan caused the local leaders in Sarawak to be wary of Tunku's intentions in view of the great disparity in socioeconomic development between Malaya and the Borneo states. There was a general fear that without a strong political institution, the Borneo states would be subjected to Malaya's colonisation. Therefore, various political parties in Sarawak emerged to protect the interests of the communities they represented.[65] On 17 January 1962, the Cobbold Commission was formed to gauge the support of Sarawak and Sabah for the proposed federation. Between February and April 1962, the commission met more than 4,000 people and received 2,200 memoranda from various groups. The commission reported divided support among the Borneo population. However, Tunku interpreted the figures as 80 percent support for the federation.[66][67] Sarawak proposed an 18-point memorandum to safeguard its interests in the federation. In September 1962, Sarawak Council Negri (now Sarawak state legislative assembly) passed a resolution that supported the federation with a condition that the interests of the Sarawak people would not be compromised. On 23 October 1962, five political parties in Sarawak formed a united front that supported the formation of Malaysia.[65] Sarawak was officially granted self-government on 22 July 1963,[68][69] and formed the federation of Malaysia with Malaya, North Borneo, and Singapore on 16 September 1963.[70][71]

.JPG.webp)

The Malaysian federation had drawn opposition from the Philippines, Indonesia, Brunei People's Party, and the Sarawak-based communist groups. The Philippines and Indonesia claimed that the British would be "neocolonising" the Borneo states through the federation.[72] Meanwhile, A. M. Azahari, leader of the Brunei People's Party, instigated the Brunei Revolt in December 1962 to prevent Brunei from joining the Malaysian federation.[73] Azahari seized Limbang and Bekenu before being defeated by British military forces sent from Singapore. Claiming that the Brunei revolt was solid evidence of opposition to the Malaysian federation, Indonesian President Sukarno ordered a military confrontation with Malaysia, sending armed volunteers and later military forces into Sarawak, which became a flashpoint during the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation between 1962 and 1966.[74][75] The confrontation gained little support from Sarawakians except from the Sarawak communists. Thousands of communist members went into Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo, and underwent training with the Communist Party of Indonesia. During the confrontation, around 10,000 to 150,000 British troops were stationed in Sarawak, together with Australian and New Zealand troops. When Suharto replaced Sukarno as the president of Indonesia, negotiations were restarted between Malaysia and Indonesia which led to the end of the confrontation on 11 August 1966.

After the formation of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the ideology of Maoism started to influence Chinese schools in Sarawak. The first communist group in Sarawak was formed in 1951, with its origins in the Chung Hua Middle School (Kuching). The group was succeeded by the Sarawak Liberation League (SLL) in 1954. Its activities spread from schools to trade unions and farmers. They were mainly concentrated in the southern and central regions of Sarawak. Communist members successfully penetrated the Sarawak United Peoples' Party (SUPP). SLL tried to realise a communist state in Sarawak through constitutional means but during the confrontation period, it resorted to armed struggle against the government.[19][note 3] Weng Min Chyuan and Bong Kee Chok were the two notable leaders of the SLL. Following this, the Sarawak government relocated Chinese villagers into security-guarded settlements along the Kuching–Serian road to prevent the communists from getting material support from the villagers. The North Kalimantan Communist Party (NKCP) (also known as Clandestine Communist Organisation (CCO) by government sources) was formally set up in 1970. In 1973, Bong surrendered to chief minister Abdul Rahman Ya'kub; this significantly reduced the strength of the communist party. However, Weng, who had directed the CCO from China since the mid-1960s, called for armed struggle against the government, which after 1974 continued in the Rajang Delta. In 1989 the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) signed a peace agreement with the government of Malaysia. This caused the NKCP to reopen negotiations with the Sarawak government, which led to a peace agreement on 17 October 1990. Peace was restored in Sarawak after the final group of 50 communist guerrillas laid down their arms.[76][77]

Notes

- ↑ Morrison, 1993. There has been serious differences between Rajah and his brother and nephew (page 14)

- ↑ Ooi, 2013. This denial of entry to Anthony ... (page 93) ... The anti-cession movement was by the early 1950s effectively "strangled" a dead letter.(page 98)

- ↑ The first Communist group to be formed in Sarawak ... (page 95)

References

- 1 2 "Niah National Park – Early Human settlements". Sarawak Forestry. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ "New pre-history timeline discovered for Borneo".

- 1 2 Faulkner, Neil (7 November 2003). Niah Cave, Sarawak, Borneo. Current World Archaeology Issue 2. Archived from the original on 23 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ The new timeline of 65,000 years was concluded when five pieces of microlithic tools that were aged 65,000 years old and a human skull that was aged 55,000 years old were discovered at part of the Niah Saves complex, Trader cave, during excavation work.

- ↑ "History of the Great Cave of Niah". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 22 November 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ "Niah Cave". humanorigins.si.edu. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 22 November 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ "Ancient Deep Skull still holds big surprises 60 years after it was unearthed".

- ↑ Hirst, K. Kris. "Niah Cave (Borneo, Malaysia) – Anatomically modern humans in Borneo". about.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ "Niah National Park, Miri". Sarawak Tourism Board. Archived from the original on 26 December 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ Zheng, Dekun (1 January 1982). Studies in Chinese Archeology. The Chinese University Press. pp. 49, 50. ISBN 978-962-201-261-5.

In case of Santubong, its association with T'ang and Sung porcelain would necessary provide a date of about 8th – 13th century A.D.

- ↑ "Archeology". Sarawak Muzium Department. Archived from the original on 12 October 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ↑ "The Fall of Melanau Kingdom and the expansion of Brunei empire".

- ↑ Brunei Rediscovered: A Survey of Early Times By Robert Nicholl p. 35 citing Ferrand. Relations, page 564-65. Tibbets, Arabic Texts, pg 47.

- ↑ Said, Sanib (2012). "Sejarah Awal Kepulauan Melayu: Lima Buah Negeri Warisan Sarawak yang Hilang (The Heritage if the Early History of Sarawak: The Five Lost Kingdom)" (PDF). Current Research in Malaysia. 1 (1): 21–50. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ↑ [Sejarah kewujudan pentadbiran dua kerajaan dikaji https://www.utusanborneo.com.my/2016/01/16/sejarah-kewujudan-pentadbiran-dua-kerajaan-dikaji]

- ↑ Donald F, Lach (15 July 2008). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume I: The Century of Discovery, Book 1. University of Chicago Press. p. 581. ISBN 978-0-226-46708-5.

... but Castanheda lists five great seaports that he says were known to the Portuguese. In his transcriptions they are called "Moduro" (Marudu?), "Cerava" (Sarawak?), "Laue" (Lawai), "Tanjapura" (Tanjungpura), and "Borneo" (Brunei) from which the island derives its name.

- ↑ Broek, Jan O.M. (1962). "Place Names in 16th and 17th Century Borneo". Imago Mundi. 16 (1): 134. doi:10.1080/03085696208592208. JSTOR 1150309.

Carena (for Carena), deep in the bight, refers to Sarawak, the Kuching area, where there is clear archaeological evidence of an ancient trade center just inland from Santubong.

- ↑ Rozan Yunos (28 December 2008). "Sultan Tengah – Sarawak's first Sultan". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Morrison, Alastair (1 January 1993). Fair Land Sarawak: Some Recollections of an Expatriate Official. SEAP Publications. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-87727-712-5.

- ↑ Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (12 November 2012). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. SEAP Publications. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-87727-712-5.

- ↑ B.A., Hussainmiya (2006). "The Brookes and the British North Borneo Company". Brunei - Revival of 1906 - A popular history (PDF). Bandar Seri Begawan: Brunei Press Sdn Bhd. p. 6. ISBN 99917-32-15-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Reece, Robert. "Empire in Your Backyard – Sir James Brooke". Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ↑ Saunders, Graham (5 November 2013). A History of Brunei. Routledge. pp. 74–78. ISBN 978-1-136-87394-2.

- ↑ James Leasor (1 January 2001). Singapore: The Battle That Changed the World. House of Stratus. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7551-0039-2.

- ↑ Alex Middleton (June 2010). "Rajah Brooke and the Victorians" (PDF). The Historical Journal. 53 (2): 381–400. doi:10.1017/S0018246X10000063. ISSN 1469-5103. S2CID 159879054. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ "Early Iban Migration – Part 1". 26 March 2007.

- ↑ Simonson, T. S.; Xing, J.; Barrett, R.; Jerah, E.; Loa, P.; Zhang, Y.; Watkins, W. S.; Witherspoon, D. J.; Huff, C. D.; Woodward, S.; Mowry, B.; Jorde, L. B. (8 April 2023). "Ancestry of the Iban Is Predominantly Southeast Asian: Genetic Evidence from Autosomal, Mitochondrial, and Y Chromosomes". PLOS ONE. 6 (1): e16338. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016338. PMC 3031551. PMID 21305013.

- ↑ "Ngepan Batang Ai (Iban Women Traditional Attire)" (PDF). 8 April 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Iban as a koine language in Sarawak". 1 May 2023.

- ↑ "Asal usul Melayu Sarawak: Menjejaki titik tak pasti". 1 May 2023.

- ↑ Mike, Reed. "Book review of "The Name of Brooke – The End of White Rajah Rule in Sarawak" by R.H.W. Reece, Sarawak Literary Society, 1993". sarawak.com.my. Archived from the original on 8 June 2003. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ Cuhaj, George S (2014). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, General Issues, 1368–1960. F+W Media. p. 1058. ISBN 978-1-4402-4267-0.

Sarawak was recognised as a separate state by the United States (1850) and Great Britain (1864), and voluntarily became a British protectorate in 1888.

- ↑ James, Stuart Olson (1996). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 982. ISBN 978-0-313-29367-2.

Brooke and his successors enlarged their realm by successive treaties of 1861, 1882, 1885, 1890, and 1905.

- ↑ "Chronology of Sarawak throughout the Brooke Era to Malaysia Day". The Borneo Post. 16 September 2011. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015.

- ↑ Lim, Kian Hock (16 September 2011). "A look at the civil administration of Sarawak". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015.

- ↑ Frans, Welman (2011). Borneo Trilogy Sarawak: Volume 1. Bangkok, Thailand: Booksmango. p. 177. ISBN 978-616-245-082-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ooi, Keat Gin (2013). Post-war Borneo, 1945–50: Nationalism, Empire and State-Building. Routledge. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-134-05803-7.

- ↑ Rujukan Kompak Sejarah PMR (Compact reference for PMR History subject) (in Malay). Arah Pendidikan Sdn Bhd. 2009. p. 82. ISBN 978-983-3718-81-8.

- ↑ "Bintulu – Places of Interest". Bintulu Development Authority. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ Marshall, Cavendish (2007). World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia, Volume 9. Bangladesh: Marshall Cavendish. p. 1182. ISBN 978-0-7614-7642-9.

- 1 2 Gullick, J. M. (1967). Malaysia and Its Neighbours, The World studies series. Taylor & Francis. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0-7100-4141-8.

- ↑ Lewis, Samuel Feuer (1 January 1989). Imperialism and the Anti-Imperialist Mind. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-2599-3.

Brooke made it his life task to bring to these jungles "prosperity, education, and hygiene"; he suppressed piracy, slave-trade, and headhunting, and lived simply in a thatched bungalow.

- ↑ "The Borneo Company Limited". National Library Board. Archived from the original on 12 October 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ↑ Sendou Ringgit, Danielle (5 April 2015). "The Bau Rebellion: What sparked it all?". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016.

The Rajah then came back days later with a bigger army and bigger guns aboard the Borneo Company steamer, the Sir James Brooke together with his nephew, Charles Brooke.

- ↑ "石隆门华工起义 (The uprising of Bau Chinese labourers)" (in Chinese). 国际时报 [International Times (Sarawak)]. 13 September 2008. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013.

- ↑ Ting, John. "Colonialism and Brooke administration: Institutional buildings and infrastructure in 19th century Sarawak" (PDF). University of Melbourne. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

Brooke also indigenised himself in terms of housing – his first residence was a Malay house. (page 9) ... Government House (Fig. 3) was built after Brooke's first house was burnt down during the 1857 coup attempt. (page 10)

- 1 2 3 Simon, Elegant (13 July 1986). "SARAWAK: A KINGDOM IN THE JUNGLE". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 November 2015.

- ↑ Saiful, Bahari (23 June 2015). "Thrill is gone, state museum stuck in time – Public". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015.

- ↑ "History of Sarawak". Brooke Trust. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ "Centenary of Brooke rule in Sarawak – New Democratic Constitution being introduced today". The Straits Times (Singapore). 24 September 1941.

- ↑ L, Klemen. "The Invasion of British Borneo in 1942".

- ↑ "The Japanese Occupation (1941 – 1945)". The Sarawak Government. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ↑ Gin, Ooi Keat (1 January 2013). "Wartime Borneo, 1941–1945: a tale of two occupied territories". Borneo Research Bulletin. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

Occupied Borneo was administratively partitioned into two-halves, namely Kita Boruneo (Northern Borneo) that coincided with pre-war British Borneo (Sarawak, Brunei, and North Borneo) was governed by the IJA, ...

- ↑ Kratoska, Paul H. (13 May 2013). Southeast Asian Minorities in the Wartime Japanese Empire. Routledge. pp. 136–142. ISBN 978-1-136-12506-5.

- ↑ Ooi, Keat Gin. "Prelude to invasion: covert operations before the re-occupation of Northwest Borneo, 1944–45". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ↑ Australia in the War of 1939-1945. Series 1 - Army - Volume VII - The Final Campaigns (1st edition, 1963) - Chapter 20 - Securing British Borneo. Australia: The Australian War Memorial. 1963. p. 491.

- ↑ "Historical Monument – Surrender Point". Official Website of Labuan Corporation. Labuan Corporation. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ↑ Rainsford, Keith Carr. "Surrender to Major-General Wootten at Labuan". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ↑ "HMAS Kapunda". Royal Australian Navy. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ Patricia, Hului (12 September 2016). "Celebrating Batu Lintang Camp liberation day on Sept 11". The Borneo Post.

- ↑ "British Military Administration (August 1945 – April 1946)". The Sarawak Government. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ↑ "Sarawak as a British Crown Colony (1946–1963)". The Official Website of the Sarawak Government. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ Thomson, Mike (14 March 2012). "The stabbed governor of Sarawak". BBC News.

- 1 2 "Anthony Brooke". The Daily Telegraph. 6 March 2011.

- 1 2 Tai, Yong Tan (2008). "Chapter Six: Borneo Territories and Brunei". Creating "Greater Malaysia": Decolonization and the Politics of Merger. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 154–169. ISBN 978-981-230-747-7.

Underlying this was a general fear that without strong political institutions, ... (page 155)

- ↑ "Formation of Malaysia 16 September 1963". National Archives of Malaysia. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ JC, Fong (16 September 2011). "Formation of Malaysia". The Borneo Post.

- ↑ Vernon L. Porritt (1997). British Colonial Rule in Sarawak, 1946–1963. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-983-56-0009-8. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ Philip Mathews (28 February 2014). Chronicle of Malaysia: Fifty Years of Headline News, 1963–2013. Editions Didier Millet. p. 15. ISBN 978-967-10617-4-9.

- ↑ "Trust and Non-self governing territories". United Nations. Archived from the original on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ "United Nations Member States". United Nations. 3 July 2006. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ↑ Ishikawa, Noboru (15 March 2010). Between Frontiers: Nation and Identity in a Southeast Asian Borderland. Ohio University Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-89680-476-0.

- ↑ "Brunei Revolt breaks out – 8 December 1962". National Library Board (Singapore). Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ United Nations Treaty Registered No. 8029, Manila Accord between Philippines, Federation of Malaya and Indonesia (31 July 1963) Archived 11 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ↑ United Nations Treaty Series No. 8809, Agreement relating to the implementation of the Manila Accord Archived 12 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 12 August 2011.

- ↑ James, Chin. "Book Review: The Rise and Fall of Communism in Sarawak 1940–1990". Kyoto Review of South East Asia. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ Chan, Francis; Wong, Phyllis (16 September 2011). "Saga of communist insurgency in Sarawak". The Borneo Post.