Mentawai traditional healers, 2017. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Approximately 64,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Mentawai language, Indonesian | |

| Religion | |

| Animism (predominantly), Islam and Christianity[2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Sakuddei |

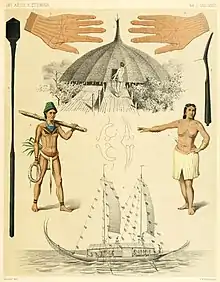

Mentawai (also known as Mentawei and Mentawi) people are the native people of the Mentawai Islands (principally Siberut, Sipura, North Pagai and South Pagai) about 100 miles from West Sumatra province, Indonesia. They live a semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle in the coastal and rainforest environments of the islands and are also one of the oldest tribes in Indonesia. The Mentawai population is estimated to be about 64,000. The Mentawai tribe is documented to have migrated from Nias – a northern island – to the Mentawai islands, living in an isolated life for centuries until they encountered the Dutch in 1621. The ancestors of the indigenous Mentawai people are believed to have first migrated to the region somewhere between 2000 and 500 BCE.[3] The Mentawai language belongs to the Austronesian language family.[4][5] They follow their own animist belief system called Arat Sabulungan, that links the supernatural powers of ancestral spirits to the ecology of the rainforest.[6][7] When the spirits are not treated well or forgotten, they might bring bad luck like illnesses and haunt those who forgot them.[6] Mentawai also have very strong belief towards objects they think are holy.[8] The people are characterized by their heavy spirituality, body art and their tendency to sharpen their teeth, a cultural practice tied to Mentawai beauty ideals. Mentawai tend to live in unison and peace with the nature around them because they believe that all things in nature have a form of spiritual essence.[6][9]

Culture and lifestyle

The Mentawai live in the traditional dwelling called the Uma which is a longhouse and is made by weaving bamboo strips together to make walls and thatching the roofs with grass, the floor is raised on stilts and is made of wood planks. Each Uma is decorated with skulls of the various animals they hunted.[10] An Uma can house three to four families. A Lalep is a smaller house containing only one family; and a Rusuk is a home for widows and bachelors.

The main clothing for men is a loin cloth made from the bark of a gum tree. Mentawai adorn themselves with necklaces and flowers in their hair and ears. Women wear a cloth wound around the waist and small sleeveless vests made from palm or banana leaves. Mentawai sharpen their teeth with a chisel for aesthetic reasons.

It is very common to see Mentawai people covered head to toe in tattoos, since they follow various traditional tribal rituals and their tattoos identify their role and social status. The tradition of tattooing called Titi, is done with cane and coconut charcoal dye, a nail, a needle, and two pieces of wood fashioned into a hammer-like stick by a shaman called Sikerei.[11] The shaman will pray for the charcoal before using it to make a tattoo.[8] Tattooing on the island is an identity and a personal or communal reflection of the people's relationship to nature, called Arat Sabulungan, although there are motivational and design differences from region to region and among clans.[12] Mentawai people believe that these tattoos allow them to bring their material wealth into the afterlife and allows their ancestors to recognize them in the afterlife.[13] Moreover, Mentawai tattoos are considered one of the oldest in the world, and symbolize the balance between foresters and nature.[8]

The Mentawai, also known as the "Flower People", never harvest a plant or take the life of an animal without asking for their spirit's forgiveness first because they believe every part of the environment has a spirit.[10] This belief is essential to their traditional religion of Arat Sabulungan. This complex cultural belief system gives reverence to the spirits of their ancestors, the sky, land, ocean, rivers, and all that is natural within. It also provides local people with the skills, knowledge, and values required to maintain a self-sufficient and sustainable lifestyle. As teachers, healers and caretakers of this indigenous knowledge, local shaman, known as Sikerei, fulfill their responsibility to the wider community by educating them in the intricacies of Arat Sabulungan.[7] They instill a comprehensive understanding of all that life is dependent upon within their people. Sikerei are the backbone of Mentawai culture and its sustainability. Presently, largely due to the gradual introduction and influence of foreign cultural, behavioral and ideological change, the number of Sikerei still practicing the Arat Sabulungan lifestyle and their role has diminished to a few small clans located in the south of Siberut island.[3][6]

The traditional knife of the Mentawai people is called Palitai, while their traditional shield is called Kurabit.[14]

Men hunt warthogs, chicken, deer, and primates.[8] Dogs are usually used to spot the animals during hunting, then the prey is shot with a bow and poisonous arrow. The poison comes from a local leaf which has been mashed and mixed with water.[10] Women and children gather wild yams and other wild food and fruits. The main food they eat is sago, a type of flour from ground palm medulla, which is usually grilled.[8] Small animals are hunted by women. The Mentawai people keep pigs, dogs, monkeys, and sometimes chickens as pets.

During the pre-independence era, the cultural influence of foreign colonials and other islanders had systematically displaced or obliterated indigenous customs and religions. In postcolonial times, the Indonesian government continued this policy with a 1954 decree that prohibited animist religions, effectively abolishing tattooing and other customs.[12] In the 1950s, the government began introducing development programs designed to integrate the Mentawai into mainstream society. While this policy may have sought to encourage social unification, in practice, it resulted in the suppression of the Mentawai's Arat Sabulungan. In extreme cases, state policy led to the burning and destruction of cultural paraphernalia used for ritual and ceremonial purposes. Moreover, Mentawai shamans, the Sikerei, were forcibly imprisoned or disrobed and removed from the forest.[15]

Due to modernization, the Mentawai people have experienced some significant change in their day-to-day lives and culture. With the introduction of Pancasila and transmigration, the majority of the Mentawai increasingly lost connection with their ancestral ways. Traditionally, the Mentawai live in family units centered upon a longhouse or uma, which are dispersed throughout the jungle. Government settlements now concentrate multiple families within a single area. Livestock, including pigs, which are the lifeblood and economy of Mentawai society, are banished from these same reserves due to introduced social policy. Moreover, the number of Mentawai people still actively practicing cultural customs has been reduced to only 1 percent of the population, isolated to the south of Siberut.[15] Under Pancasila, the five principles for Indonesian state philosophy formulated by the Indonesian nationalist leader Sukarno, the Indonesian Government also began to enforce their new nationwide religious policies issuing a decree declaring that all Indonesian people must belong to one of the five recognized religions (Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, and Buddhism). For the Mentawai Islands, this resulted in an immediate influx of missionaries and an increase in violence and pressure on the people to adopt change.[3] Mentawai people are also facing a challenge in their day-to-day learning. In the government-sponsored schools, Mentawai children are encouraged to speak Indonesian.[15]

One major environmental problem for the Mentawai people is deforestation as their rainforests contain rich timber. In 2015, 20,000 hectares of forest was set aside as a palm oil plantation area in Siberut. Local NGOs pressured the Indonesian authorities to cancel the permit, which included Mentawai traditional lands. However, even with this success, the possibility of logging remains a constant threat on the islands.[15] More than 80 percent of the Mentawai Islands are owned and managed by the state, which makes it difficult for Mentawai people to manage their own lands and natural resources.[16]

Without the collective voice of the Mentawai community, their rights and the protection of Siberut's natural resources will be entirely subject to state control. Thus, beginning in 2009 members of the Mentawai community recognized the need to preserve their traditions as a means of improving their health, well-being and quality of life. As a result, they began seeking change, having surveyed the wider community and discerned that an overwhelming majority wanted to protect and perpetuate their culture.[15] One proposed strategy includes community driven indigenous educational programs. They are designed to provide indigenous Mentawai with the opportunity to reconnect with and learn the most important and relevant aspects of their cultural and environmental heritage. The programs, while still being developed and implemented, will run in conjunction with mainstream education and will be taught by the Mentawai for the Mentawai organization.[15] Another promising program called "The Cultural and Ecological Education Program" provides opportunities for Mentawai people to learn the aspects of indigenous education and lifestyle they deem most important for their current and future prosperity.[3] There is great optimism among the community that these programs will be a success, however, significant financial investment is needed to ensure they flourish in the years to come.

Various shops and technology have been brought into the tribe land because of globalization, and tours are even given to those who want to experience the daily life of the tribe and interact with its inhabitants.[10]

Popular culture

- BBC Two's Tribal Wives: Mentawai.[17]

- The documentary film 'As Worlds Divide' documents the lives of modern Mentawai people and premiered in Melbourne on March 24, 2017.[18] The film was available as a part of an international 'Watch a film, save a culture' campaign in October 2017.

- Law of the Jungle: Sumatra

See also

References

- ↑ "Mentawai of Indonesia". People Groups. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "Mentawai Islands Village & Culture".

- 1 2 3 4 "History". Suku Mentawai. 2012-06-30. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ "Mentawai". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ↑ "Mentawai Tribe". Authentic Indonesia. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- 1 2 3 4 Singh, Manvir; Kaptchuk, Ted J.; Henrich, Joseph (January 2021). "Small gods, rituals, and cooperation: The Mentawai water spirit Sikameinan". Evolution and Human Behavior. 42 (1): 61–72. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.07.008.

- 1 2 Singh, Manvir; Henrich, Joseph (2020). "Why do religious leaders observe costly prohibitions? Examining taboos on Mentawai shamans". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2: e32. doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.32. ISSN 2513-843X. PMC 10427447.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "5 Things You Need To Know About Mentawai Tribe". brilio.net. 26 January 2017. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- ↑ "The Mentawai People". Authentic Sumatra. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Life of the Mentawai Tribe". Fabien Astre. 2017-12-29. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ "Mentawai Islands Village & Culture". HT's Mentawai Surf Resort. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- 1 2 Dale Rio (2012). Planet Ink: The Art and Studios of the World's Top Tattoo Artists. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-4229-9.

- ↑ "Mentawai Tribe". www.mentawaitribe.com. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ Zonneveld, Albert G. van (2002). Traditional Weapons of the Indonesian Archipelago. Koninklyk Instituut Voor Taal Land. ISBN 90-5450-004-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dungey, Grace; Rodway, Nicholas (October 11, 2017). "By Mentawai for Mentawai: How Community-driven Education Can Save a Tribe". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ Gaworecki, Mike (2016-06-07). "Timber Plantations Are the Latest Threat Facing Indonesia's Mentawai Islands". Mongabay Environmental News. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ "Tribal Wives, Series 1, Mentawai/Indonesia". BBC Two. Retrieved 2014-11-16.

- ↑ "As Worlds Divide". Roebeeh Productions. Retrieved 2017-06-06.

Further reading

- Henley, Thom; Limapornvanich, Taveepong (2001). Living Legend of the Mentawai. Ban Thom Pub. ISBN 0-9689091-2-4.