| Kanawha Valley Campaign of 1862 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

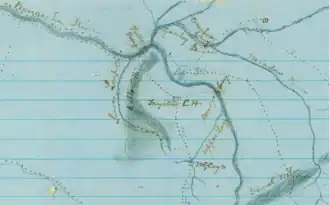

Kanawha River and surrounding territory | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| United States (Union) | Confederate States | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Joseph A.J. Lightburn

| William W. Loring | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

District of the Kanawha

|

Dept. of SW Virginia

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~ 5,000 | ~ 5,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

237

|

404

| ||||||

| Casualties exclude Jenkins' raid | |||||||

The Kanawha Valley Campaign of 1862 was Confederate Major General William W. Loring's military campaign to drive the Union Army out of the Kanawha River Valley during the American Civil War. The campaign took place from September 6 through September 16, 1862, although an important raid that had impact on the campaign started on August 22. Loring achieved success after several skirmishes and two battles (at Fayetteville and Charleston), and Union troops retreated to the Ohio River and the safety of the state of Ohio.

Although the Kanawha Valley was in the southwestern portion of the Confederate state of Virginia at the time of the battle, it became part of the Union state of West Virginia in 1863. Despite West Virginia's impending break away from the Confederacy, its citizens in the Kanawha Valley were divided in loyalty to the two causes. Confederate leadership desired to regain control of the region and its valuable salt mines, and the river valley was seen as a source for new army recruits.

During August 1862, Union Brigadier General Jacob Dolson Cox was ordered to move his Kanawha Division from southwestern Virginia to Washington as reinforcement for Major General John Pope's Army of Virginia. Cox left behind a small force of about 5,000 men, which was under the command of Colonel Joseph Andrew Jackson Lightburn and headquartered at Gauley Bridge. Confederate leadership found out about the depleted force, and sent Major General William W. Loring to drive the remaining Union soldiers out of western Virginia. Despite Loring's success, he was removed from command one month later because of his lack of cooperation with his superiors. Cox returned to Ohio, and organized troops to retake the Kanawha Valley. Confederate troops evacuated the valley, and the Union army entered Charleston on October 30.

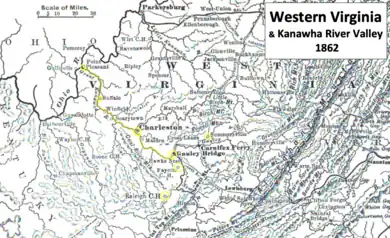

Background

In 1861, Union forces gained control of a large portion of southwestern Virginia. Brigadier General Jacob Dolson Cox was commander of the Kanawha Division, and it controlled southwestern Virginia along the Kanawha River Valley.[1][Note 1] The western portion of Virginia had few good roads and few settlements.[3] Using small steamboats from the Ohio River, the Kanawha River could be navigated for about 70 miles (110 km) to a point about 10 miles (16 km) upstream from Charleston, which meant the river could be used to transport troops and supplies.[1]

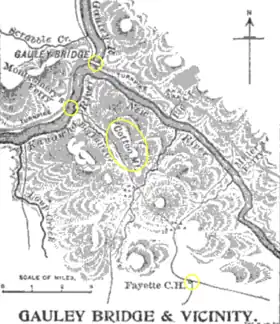

Further upstream (with non-navigable portions), the Kanawha River is formed by the meeting of the New River and the Gauley River at the community of Gauley Bridge. That community was important not only for its river connections, but also because the James River and Kanawha Turnpike ran through it and was intersected by another road that ran northeast to Summersville and beyond.[4] The Kanawha River Valley portion of Virginia became part of the Union state of West Virginia on June 20, 1863.[5]

On August 14, 1862, Cox began moving his Kanawha Division to Washington as reinforcement for Major General John Pope's Army of Virginia.[6] Exceptions to Cox's orders were about 5,000 troops left behind and put under the command of Colonel Joseph Andrew Jackson Lightburn.[7] Soon after Cox left the Kanawha Valley, Pope's quartermaster was captured along with numerous records, and Confederate leaders learned that Cox had left only 5,000 men in the Kanawha Valley at posts around Gauley Bridge. In 1862, the Kanawha Valley was important to the Confederacy because of its salt deposits and its potential for new army recruits.[8][Note 2] Major General William W. Loring was ordered to clear the Kanawha Valley of Union soldiers, and then move northeast to form a junction with more Confederate soldiers in the Shenandoah Valley.[10] Loring's campaign to accomplish this objective began September 6 and ended September 16, although an important raid that was part of Loring's plan began on August 22.[11][Note 3]

Opposing forces

Union army

Colonel Joseph Andrew Jackson Lightburn assumed command of the District of the Kanawha, Department of the Ohio, on August 17, 1862.[14] He was very religious and had little combat experience.[15] His forces were:

- The First Provisional Brigade was commanded by Colonel Edward Siber.[11] The brigade consisted of two infantry regiments: the 34th Ohio Infantry (a.k.a. Piatt's Zouaves) was commanded by Colonel John T. Toland, and Siber's 37th Ohio Infantry was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Louis von Blessing.[16] Artillery consisted of two mountain howitzers and two smooth bore pieces.[17] Siber had over 20 years of service as a German soldier in Prussia and Brazil.[18]

- The Second Provisional Brigade was commanded by Colonel Samuel A. Gilbert.[11] It consisted of three infantry regiments plus two companies of cavalry: Gilbert's 44th Ohio Infantry was commanded by Major Ackber Orville Mitchell, the 47th Ohio Infantry was commanded by Colonel Lyman S. Elliott, and the 4th Loyal Virginia Infantry was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William H.H. Russell.[Note 4] The brigade's two cavalry companies were commanded by Major John J. Hoffman from the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry Regiment.[19] Artillery consisted of two 10-pounder rifled pieces, four mountain howitzers, one iron smooth-bore 6-pounder, and one brass 10-pounder rifled James.[20] Gilbert had combat experience, having fought in the Battle of Cheat Mountain and the Battle of Lewisburg.[21]

- The 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry Regiment, later named 2nd West Virginia Cavalry, was commanded by Colonel John C. Paxton.[22] The regiment was often scattered at multiple locations. In addition to the detachment of two companies commanded by Major Hoffman, Lieutenant Colonel Rollin L. Curtis commanded other detachments.[23][Note 5]

- The 9th Loyal Virginia Infantry was also not part of a brigade.[23] The regiment was often split and consisted of only about 500 effectives. Colonel Leonard Skinner was the commander of the 9th West Virginia Infantry (and unhappy about the splits), and Lieutenant Colonel William Cooper Starr commanded detachments.[25]

- Lightburn also had the assistance of the 153rd Militia and Home Guard of Kanawha County. Other home guard units and detachments, not under Lightburn's command, patrolled elsewhere in western Virginia and along the Ohio side of the Ohio River.[26]

Confederate army

Major General William W. Loring commanded the Department of Southwestern Virginia.[11] He had been a soldier since the age of 14, was a sergeant at the age of 17, and fought in the Second Seminole War and the Mexican–American War.[15] Under his command were six infantry regiments, three infantry battalions, and five batteries.[27]

- The First Brigade was commanded by Brigadier General John Echols. It consisted of the 50th and 63rd Virginia Infantry regiments, plus the 23rd Virginia Infantry Battalion (a.k.a. Derrick's Battalion).[28]

- The Second Brigade was commanded by Brigadier General John S. Williams.[27] Under his command were 26th Virginia Infantry Battalion (a.k.a. Edgar's Battalion, the 22nd Virginia Infantry Regiment, and the 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment.[29] Major George M. Edgar was a prisoner of war during the campaign, so his battalion was temporarily commanded by Major Alexander M. Davis of the 45th Virginia Infantry.[30] Colonel George S. Patton commanded the 22nd Virginia Infantry, and Colonel William Henry Browne commanded the 45th Virginia Infantry.[31]

- The Third Brigade was commanded by Colonel Gabriel C. Wharton.[32] Under his command were the 51st Virginia Infantry Regiment and the 30th Virginia Sharpshooters Battalion (a.k.a. Clarke's Battalion)[33] Lieutenant Colonel Ludwig Augustus Forsberg commanded the 51st Virginia Infantry, while Lieutenant Colonel John L. Clarke commanded Clark's Battalion.[34]

- The Fourth Brigade was commanded by Colonel John McCausland and included McCausland's 36th Virginia Infantry Regiment and the 60th Virginia Infantry Regiment, although Loring never mentions the 60th Virginia in his reports.[35] Commanded by Colonel Beuhring H. Jones, the 60th Virginia is thought to have guarded supply wagons and not participated in fighting.[36]

- Artillery Battalion, Army of Southwestern Virginia, was commanded by Major John Floyd King. The battalion consisted of Bryan's, Chapman's, Lowry's, Otey's, and Stamps' (a.k.a. Ringgold Battery) batteries.[37]

- Jenkins' Cavalry was commanded by Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins – He had seven companies from the 8th Virginia Cavalry Regiment, which were led by Colonel J. M. Corns. He also had five additional companies of mounted men led by Captain W. R. Preston.[12] Many of those men were from the 14th Virginia Cavalry Regiment.[38] The entire force totaled to about 500 men.[12]

- Salyer's Cavalry was the portion of the 8th Virginia Cavalry that did not go on Jenkins' raid and remained with Loring. It was commanded by Major Logan H.N. Salyers.[39] It included at least three companies normally part of a battalion commanded by William Henderson French, and may have been assisted by Thurmond's Partisan Rangers.[40]

- Virginia State Line was a partisan military force of nearly 2,000 men created with the purpose of recovering western Virginia and protecting various salt mines. The militia unit was commanded by Major General John Buchanan Floyd. It was not popular with Confederate army leaders, and did not employ strict discipline.[41]

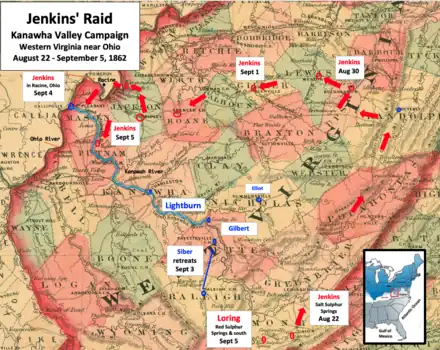

Jenkins' Raid

Confederate Major General Loring planned to take control of the Kanawha River Valley by leading a large force in an assault of Union forces located upriver in Raleigh, Fayette, and Kanawha counties. Part of his plan included sending a cavalry force through 500 miles (800 km) of Union–controlled territory to cut off the Union route of retreat downriver.[38] On August 22, he began the execution of his plan by sending north a cavalry force commanded by Brigadier General A. G. Jenkins.[42]

Jenkins' mission was to attack the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and then move to the rear of the Union forces that occupied strategic points near the beginning of the Kanawha River.[43] The railroad was located far to the north, and at least one historian believes the railroad portion of the mission was merely a diversion—Loring knew that Jenkins would not be able to damage the railroad, but the threat would draw attention away from Loring's front and Jenkins' principal goal of cutting off the Union route of retreat.[42] Jenkins began this mission with a 550-man mounted force that started north from near Salt Sulphur Springs.[44] Later in the day, he sent one company away for another mission on the south side of the Kanawha River.[42]

Jenkins' circular route began with a northern movement in the Cheat River Valley before moving west and south.[43] On August 28, Jenkins encountered six Union pickets about 15 miles (24 km) south of a Union post near Beverly, and learned that the Union position would be difficult to attack.[45] He decided to bypass the Union fortification and abandon the attack on the railroad.[43] Moving west, Jenkins captured a Union supply depot at the town of Buckhannon on August 30.[46] Using captured arms and ordnance, he was able to resupply his poorly-armed men with Enfield and Harper's Ferry rifles.[47] Jenkins continued west, moving through Weston, Glenville, Spencer, and Ripley.[48] Jenkins crossed the Ohio River into Ohio on September 4 with part of his force.[49] This was the first Confederate invasion of Ohio, and the crossing was made near Ravenswood at Sand Creek Riffle in Meigs County.[50] After midnight, he crossed back into Virginia near Racine at Wolf's Bar.[51] From there, he made a feint toward Point Pleasant, Virginia but took his command to the small town of Buffalo located up the Kanawha River. His mission was accomplished by September 5, and Union forces upriver were not sure of his location.[52]

Loring attacks

The Union commander, Colonel Joseph Lightburn, kept his headquarters at Gauley Bridge.[53] By August 31, Lightburn was aware of rumors that a Confederate force of 10,000 men was preparing to attack the Kanawha River Valley.[54] Loring's Confederate force actually consisted of about 5,000 men instead the rumored 10,000, but he expected to add to it by recruiting and organizing existing local militias.[10] In early September, Lightburn moved his First Brigade from Raleigh Court House to Fayette Courthouse (a.k.a. Fayetteville).[Note 6] This put the majority of the Union forces closer together at Fayetteville, Gauley Bridge, and Summerville. All three posts were near major roads, and Gauley Bridge is at the junction of the Gauley and New rivers, which combine to form the Kanawha River.[54]

Aware of the possibility of Jenkins' Confederate cavalry near his flank or rear, Lightburn sent a large portion of the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry, commanded by Colonel John C. Paxton, to confront Jenkins.[56] Several companies of the 4th Loyal Virginia Infantry were sent separately.[57] On September 8, the Union cavalry discovered that Jenkins had his headquarters at the William C. Miller house near Barboursville.[58] That evening, they surrounded the house, but Jenkins and his staff escaped through the rear garden. The entire Confederate force abandoned its camp and moved up the Guyandotte River towards Logan County.[58] Although news of the event at Barboursville led Lightburn to believe that the threat from Jenkins was reduced, that was not entirely true.[59] When the fighting took place in Fayette County two days later, Jenkins moved his troops to Logan Court House and then Wyoming Court House. Unable to communicate with Loring, he eventually moved his men west toward the mouth of the Coal River (Kanawha County) in an attempt to block any Union retreat.[60]

Fayette Court House

In early September, Loring began moving toward the Union positions via the Princeton area, Flat Top Mountain, and then Raleigh Court House.[10] Loring's men camped at McCoy's Mill (now Glen Jean, West Virginia) on the evening of September 9, which was about nine miles (14 km) south of Fayette Court House. At Fayette Court House, the Union First Brigade commanded by Colonel Edward Siber consisted of less than 1,200 men.[61] Loring sent one brigade on a mountainous path around Fayetteville to prepare for an attack on Siber's right flank and rear. The remaining portion of Loring's army made a frontal attack on September 10 via the Princeton-Raleigh Road. The first engagements occurred a few miles south of Fayetteville between 11:00 am and 12:00 pm.[62] The frontal attack was led by the 45th Virginia Infantry, and that regiment did most of its fighting from 2:00 pm until dark.[63]

The flanking force made contact with Siber's men around 2:00 pm, and was at Siber's right flank instead of behind him.[64] Some of the most important fighting happened near the road from Fayetteville to a ferry near Gauley Bridge.[65] The Union army's 34th Ohio Infantry, led by Colonel John Toland, fought at that location. That regiment's casualties, alone, were estimated to be 16 killed and 57 wounded.[66] Elsewhere at 3:00 pm, Lightburn ordered his Second Brigade to concentrate near Gauley Bridge and be prepared to assist in the First Brigade's retreat.[67] Around 5:00 pm, the Union force at Summersville was ordered to destroy excess supplies.[68] The day's fighting at Fayetteville ended by 9:00 pm.[69] Between 1:00 and 2:00 am on September 11, Siber's men quietly abandoned Fayetteville.[70]

More fighting in Fayette County

During the morning of September 11, the Confederate army discovered that the Union army had abandoned Fayetteville. A pursuit was started, but it was slowed by trees that had been chopped down and placed in the road.[71] Lightburn sent four companies from the 47th Ohio Infantry to assist Siber's First Brigade, and they met at the mountain top of Cotton Hill (between Fayetteville and the Kanawha River). At that location they could see the pursuing Confederate forces, and Siber continued the retreat while leaving a small force with artillery to delay the Confederates. Many from the retreating Union force panicked while retreating north.[72] However, the Union artillery force had been placed in a superior position, and drove the Confederates off the mountain despite a flanking movement. Fighting was over by about noon, and the Union artillerists escaped.[73]

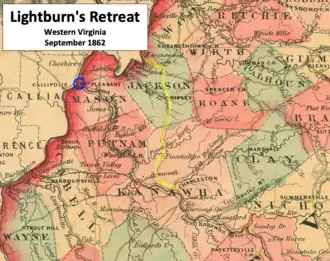

Although not under attack, the Union troops in Summerville began moving toward Gauley Bridge early in the morning on September 11.[70] Lightburn believed his entire force would need to retreat, and their probable destination was Point Pleasant on the Ohio River at the mouth of the Kanawha River.[11] Lightburn's Second Brigade, commanded by Colonel Samuel Gilbert, had been at various positions north of the Kanawha and New rivers. During Siber's morning fighting, Gilbert positioned artillery on the north side of the Kanawha River at Montgomery Ferry. The artillery and supporting forces totaled to less than 600 men, and they protected Siber's supply wagons as they ferried across the river.[74] Siber's wagons joined Lightburn's main force and continued moving west down the north side of the Kanawha River, while Siber's men moved in the same direction down the south side of the river. Most of the afternoon's fighting at Montgomery Ferry consisted of Gilbert's artillery against Confederate artillery.[75] Although Gilbert's men set the ferry boat on fire and continued their retreat west, Confederate soldiers swam across the river and extinguished the blaze. The Confederate pursuit was continued on both sides of the river.[76] More skirmishes occurred on that day at Loup Creek, Armstrong's Creek, Miller's Ferry, Gauley Ferry, and near Cannelton.[77]

Charleston and Ohio

Camp Piatt was a Union outpost on the Kanawha River about 10 miles (16 km) upriver (east) from Charleston.[78] On September 12, Lightburn arrived at Camp Piatt, and he believed that about 8,000 Confederates were in the valley. He knew he was being pursued by Loring, and thought Major General John B. Floyd was moving his partisan force to a point downriver from Charleston (Coals Mouth) to cut off the Union retreat.[79] More Union troops arrived at Camp Piatt throughout the rainy day.[80] Siber's brigade crossed the Kanawha River near Camp Piatt, and Lightburn's command was reunited.[81]

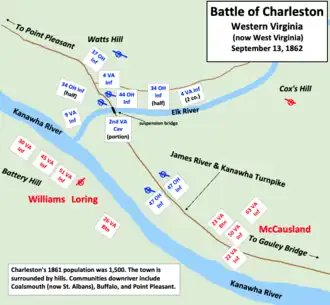

Just after midnight (September 13), Lightburn's men began moving downriver to Charleston.[82] The town's population for 1861 was about 1,500, and it was located on the Kanawha River and the James River and Kanawha Turnpike. On the downriver side of town, the Elk River empties into the Kanawha River, and travelers on the turnpike must cross the Elk River on a suspension bridge.[83] Many of Lightburn's troops took a defensive position on the downriver (west) side of the Elk River, while the remaining troops took forward positions on the east side of the river.[84] Union pickets began being driven back around 9:30 am.[85] Loring's pursuing Confederate troops were led on the north side of the Kanawha River by Colonel John McCausland, and on the south side of the river by Brigadier General John S. Williams. Skirmishing began on the north side of the river about one mile (1.6 km) from Charleston. On the south side, Williams used his artillery and sharpshooters against Union skirmishers.[86]

Retreat to Ohio

By 1:00 pm, the fighting was described as "heavy cannonading and musket fire" as both sides made use of their artillery.[87] At that time, Lightburn's supply wagons were already moving northwest down the Ripley Road—not the Charleston and Point Pleasant road than ran along the Kanawha River to Point Pleasant. At 2:00 pm, Union troops began withdrawing and setting fire to their supplies located in town.[87] Lightburn's choice to retreat to Ripley instead of directly to Point Pleasant enabled his force to avoid a possible confrontation with either Floyd or Jenkins where the Coal River emptied into the Kanawha River (a.k.a. Coalsmouth).[88] In addition, the Charleston and Point Pleasant road route to Point Pleasant would continuously be within the range of the Confederate artillery currently on the south side of the Kanawha River.[89] Once all Union troops had crossed the Elk River around 3:30 pm, the Elk River suspension bridge was destroyed.[90] The two sides traded cannon fire across the Elk River until sunset, but their artillery had little effect.[91] Lightburn continued north toward Ripley until he reached Sissonville, West Virginia, where he camped for the night. The battle was over and Loring possessed Charleston.[92]

On September 14, the Confederates constructed a pontoon bridge over the Elk River and camped on the other side. The pursuing force was about 4,000 men, with detachments left at Gauley Bridge and Fayetteville.[93] The pursuit was soon abandoned, since they had left their supply trains behind earlier in their effort to catch the retreating Union army. Loring's report also said that the enemy was getting close to the Ohio River, making it "useless to pursue him farther".[94] Loring's main force settled in at Charleston, and began taking inventory of captured supplies.[94]

Lightburn's men continued their retreat. On September 15, the Union advance guard reached Ravenswood on the Ohio River, while some of the main force reached Ripley.[95] On the next day, Union troops moved from Ripley to Ravenswood, and began crossing the Ohio River. The 4th Loyal Virginia, with the artillery, boarded barges destined for Point Pleasant. Other troops crossed the river on steamboats and barges, and began marching to Point Pleasant on the Ohio side of the river.[95] The portion of the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry that pursued Jenkins was the only unit from Lightburn's command that did not cross into Ohio, and it moved to Point Pleasant via the Virginia side of the Ohio River.[96] Although Lightburn's report cites September 16, most sources say all of the Union army reached Point Pleasant by the evening of September 18.[97]

Aftermath

On September 19, Union leaders attached Lightburn's force to the Department of the Ohio, which was commanded by Major General Horatio G. Wright.[98] The Confederate army would occupy Charleston for about 40 days.[83] In early October, Cox was promoted to major general and sent back to Point Pleasant to retake the Kanawha River Valley.[99] The Confederate army began withdrawing from the river valley on October 9.[100] Citing lack of cooperation, Confederate leadership removed Loring from command on October 15, and his replacement was Major General John Echols.[101] Cox began his Kanawha Expedition to retake the river valley on October 20.[102] On October 30, Cox crossed the Elk River and reoccupied Charleston, which had already been abandoned by the Confederate army.[102]

Lightburn would eventually become a brigadier general, and commanded a brigade in William Tecumseh Sherman's Atlanta campaign.[103] Siber continued to be a brigade commander and resigned in 1864 due to bad health.[104] In 1864, Gilbert's 44th Ohio Infantry was reorganized and became the 8th Ohio Cavalry Regiment.[105] Toland was killed in 1863 in the Wytheville Raid.[106] Loring's career in Virginia was over, but he served in the Army of Mississippi, and assumed command of that army when Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk was killed.[107] Echols suffered a major defeat in 1863 in the Battle of Droop Mountain, which was one of the last major battles in West Virginia.[108] McCausland became infamous for the 1864 Burning of Chambersburg, and he then suffered a major defeat in the Battle of Moorefield.[109] Wharton commanded a division in Jubal Early's Army of the Valley, fighting in battles such as Third Winchester, Fisher's Hill, and Cedar Creek.[110] Williams commanded a cavalry brigade in the Atlanta Campaign.[111] Jenkins was mortally wounded in 1864 in the Battle of Cloyd's Mountain.[112]

Casualties

Confederate casualties reported by a surgeon totaled to 23 killed, 5 mortally wounded, and 38 wounded.[113] These casualties do not include those incurred by Jenkins' cavalry. For Loring's main force, 16 were killed at Fayetteville, plus 4 mortally wounded and 28 wounded. At Cotton Hill, 1 man was killed, 1 was mortally wounded, and 2 were wounded. One man was accidentally wounded at Montgomery's Ferry, but the Confederate surgeon did not include the accident in his total. At Charleston, 6 were killed and 8 wounded. Well over half of the casualties occurred at Fayetteville.[113] One historian, again excluding numbers for Jenkins' cavalry, used newspapers, diaries, letters, and other miscellaneous sources to compile more accurate numbers.[114] His total is 404 casualties, including 29 killed, 105 wounded, and 270 missing (captured, deserted, or other).[115]

Cox says the loss for Siber and Gilbert was 25 killed, 95 wounded, and 175 missing—which totals to 295. He also says Siber's loss was much higher than Gilbert's, and the "missing" counts are not exact.[89] Using a method like that used for the Confederate casualties, one historian estimates a total of 237 Union casualties. This includes eight casualties from regiments not under Lightburn's command that patrolled near the Ohio River, plus one militia. The count of 237 consists of 30 killed, 79 wounded, and 128 missing (captured, deserted, or other).[115]

Performance and preservation

Initially, newspaper reports were positive concerning Lightburn's performance. The Cleveland Morning Leader said, "The retreat was undoubtedly a masterly movement, and does great credit to Colonel Lightburn."[116] However, Cox later wrote a different perspective. He mentions that "...either of the brigades intrenched at Gauley Bridge could have laughed at Loring. The river would have been impassable, for all the ferry-boats were in the keeping of our men on the right bank, and Loring would not dare pass down the valley leaving a fortified post on the line of communications by which he must return."[117] He also wrote that "Lightburn's disaster" was "embarrassing to the government."[118] Loring had done what he said he would do, and that was drive the Union army out of the Kanawha valley back to Ohio.[96]

The Kanawha River Valley Campaign of 1862 is one of the most neglected events of the American Civil War.[119] The battlefields at Fayetteville and Charleston are now covered by modern towns.[120][121] Some of the campaign's events and places are memorialized with historical markers. Fayetteville has historical markers commemorating the 1862 battle and another battle that occurred in 1863.[122] Not far from Charleston is a historical marker for Camp Piatt, near Belle, West Virginia, posted by the West Virginia Department of Culture and History.[123] In Charleston, the restored Ruffner Log House (a.k.a. Rosedale) was used by Lightburn as his headquarters.[124] Two historical markers commemorate the invasion of Ohio by Jenkins. In West Virginia, a highway marker titled "Ohio River Ford" marks the spot at Ravenswood where Jenkins crossed into Ohio.[50] On the Ohio side, a historical marker titled "First Ohio Invasion" discusses the invasion, and is placed at Buffington Island north of the actual crossing point.[125]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Cox would eventually become governor of Ohio, as would two men from the Kanawha Division's 23rd Ohio Infantry Regiment, Rutherford B. Hayes and William McKinley. Both Hayes and McKinley also became president of the United States.[2]

- ↑ Salt, an essential part of the diet for humans and livestock, was also used for preserving meat during the time of the American Civil War.[9]

- ↑ Loring's campaign to drive the Union Army out of the Kanawha River Valley took place from September 6 through September 16, 1862, according to the Official Records.[11] However, an important raid to partially surround the Union army, called "Jenkins' Expedition in West Virginia and Ohio" in the Official Records, started on August 22.[12] Historian Frederick H. Dyer calls Loring's Kanawha campaign "Campaign in the Kanawha Valley", and writes that it occurred on September 6 through September 16, 1862.[13]

- ↑ Prior to West Virginia becoming a state on June 20, 1863, Virginia had Union and Confederate military units. Those units loyal to the Union were often differentiated from their Confederate counterparts by adding "loyal" to their name. Eventually these loyal Virginia units were identified as West Virginia units.[5]

- ↑ Curtis is identified as a major in Lightburn's September 24 report, but the regimental historian notes that Curtis was promoted to lieutenant colonel and commissioned on August 19.[24]

- ↑ At the time of the American Civil War, some of the small county seats were identified with the county name followed by "Court House". For example, Beckley, Virginia (later Beckley, West Virginia) is identified on some maps as "Beckley", but it is identified in other maps as "Raleigh C.H." or Raleigh Court House. Beckley is the county seat of Raleigh County.[55]

Citations

- 1 2 Cox 1900, pp. 63–64

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 44

- ↑ Starr 1981, pp. 154–156

- ↑ Cox 1900, pp. 80–81

- 1 2 Lowry 2016, p. vi

- ↑ Cox 1900, pp. 224–226

- ↑ Cox 1900, pp. 226–227

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 25

- ↑ "Geology and the Civil War in Southwest Virginia: The Smyth County Salt Works" (PDF). Commonwealth of Virginia, Division of Mineral Resources (August 1996). Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- 1 2 3 Cox 1900, p. 392

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Scott 1887, p. 1057

- 1 2 3 Scott 1885, p. 757

- ↑ Dyer 1908, p. 973

- ↑ Scott 1887, pp. 1058–1060

- 1 2 Lowry 2016, p. 5

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 29–30

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 31

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 29

- ↑ Scott 1887, p. 1063

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 33

- ↑ Sutton 2001, p. 56

- 1 2 Scott 1887, pp. 1058–1059

- ↑ Sutton 2001, p. 55

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 35

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 37

- 1 2 Scott 1887, p. 1081

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 8

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 10

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 11

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 12–14

- ↑ Scott 1887, p. 1088

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 14

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 15–16

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 16

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 18

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 19

- 1 2 Lowry 2016, p. 45

- ↑ Evans 1899, p. 65 (WV section)

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 22–23

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 23

- 1 2 3 Lowry 2016, p. 49

- 1 2 3 Evans 1899, p. 62 (WV section)

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 46–49

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 53

- ↑ Scott 1885, pp. 758–759

- ↑ Scott 1885, p. 759

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 61–66

- ↑ Evans 1899, p. 63 (WV section)

- 1 2 Lowry 2016, p. 70

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 73–74

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 74–75

- ↑ Cox 1900, p. 393

- 1 2 Lowry 2016, p. 59

- ↑ Guiley 2019, p. 206

- ↑ Sutton 2001, p. 59

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 84

- 1 2 Sutton 2001, p. 60

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 92–93

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 166–167

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 94

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 110–111

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 144

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 113–114

- ↑ Scott 1887, p. 1061

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 129

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 133

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 135

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 137

- 1 2 Lowry 2016, p. 141

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 145

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 152

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 153

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 158

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 160

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 163–164

- ↑ "West Virginia Civil War Battles". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ↑ Sutton 2001, p. 63

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 169

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 172

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 175

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 183

- 1 2 Lowry 2016, p. 181

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 192

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 195

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 193

- 1 2 Lowry 2016, p. 203

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 208–209

- 1 2 Cox 1900, p. 396

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 214

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 225

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 233

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 239

- 1 2 Scott 1887, p. 1071

- 1 2 Lowry 2016, p. 247

- 1 2 Sutton 2001, p. 61

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 256

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 259

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 299

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 315

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 329

- 1 2 Lowry 2016, p. 336

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 71

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 380

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 382

- ↑ Sutton 2001, p. 92

- ↑ "William W. Loring". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Droop Mountain". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ↑ Eicher 2001, pp. 718–719

- ↑ Eicher 2001, pp. 746–749

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 397

- ↑ "CWSAC Battle Summaries – Cloyd's Mountain". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on February 17, 2005. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- 1 2 Lowry 2016, p. 246

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 422

- 1 2 Lowry 2016, p. 423

- ↑ "The Advance of the Rebels into the Kanawha Valley – Retreat of Colonel Lightburn (page 2 center column)". Cleveland Morning Leader (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). September 25, 1863.

- ↑ Cox 1900, pp. 396–397

- ↑ Cox 1900, p. 397

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. iii

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 101

- ↑ Lowry 2016, pp. 195–196

- ↑ "West Virginia Archives and History – Battle of Fayetteville". West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 168

- ↑ "The Craik-Patton House (scroll down to The Ruffner Log House)". Craik-Patton, Inc., a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ↑ Lowry 2016, p. 71

References

- Cox, Jacob Dolson (1900). Military Reminiscences of the Civil War Volume I – April 1861 – November 1863. New York City: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-3-84951-384-9. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- Dyer, Frederick H. (1908). A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion – Volume III. Des Moines, Iowa: Dyer Pub. Co. OCLC 1028851810. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- Eicher, David J. (2001). The Longest Night - A Military History of the Civil War. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-74321-846-7.

- Evans, Clement A., ed. (1899). Confederate Military History: A library of Confederate States History.... (Volume II). Atlanta, Georgia: Confederate Publishing Company. OCLC 951143. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (2019). Big Book of West Virginia Ghost Stories. Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-1-49304-399-6. OCLC 1108619435.

- Hess, Earl J. (2013). Kennesaw Mountain: Sherman, Johnston, and the Atlanta Campaign. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-46960-212-7. OCLC 1076716580.

- Lowry, Terry (2016). The Battle of Charleston and the 1862 Kanawha Valley campaign. Charleston, West Virginia: 35th Star Publishing. ISBN 978-0-96645-348-5. OCLC 981250860.

- Scott, Robert N., ed. (1885). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XII Part II. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 427057. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- Scott, Robert N., ed. (1887). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XIX Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 427057. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- Starr, Stephen Z. (1981). Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 4492585.

- Sutton, Joseph J. (2001) [1892]. History of the Second Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry Volunteers, During the War of the Rebellion. Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press. ISBN 978-0-9628866-5-2. OCLC 263148491.

External links

- List of West Virginia Civil War Battles - National Park Service

- Drawing of Fayetteville April 1863 - West Virginia University, West Virginia & Regional History Center

- Newspaper excerpts and Toland's report – West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History