Konstantin Rodzaevsky | |

|---|---|

Константин Родзаевский | |

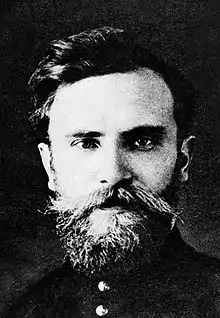

Rodzaevsky in 1934 | |

| Secretary General of the Russian Fascist Party | |

| In office 26 May 1931 – 1 July 1943 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Konstantin Vladimirovich Rodzaevsky 11 August 1907 Blagoveshchensk, Russian Empire |

| Died | 30 August 1946 (aged 39) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Cause of death | Execution by shooting |

| Political party | Russian Fascist Party |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature |  |

Konstantin Vladimirovich Rodzaevsky (Russian: Константин Владимирович Родзаевский; 11 August [O.S. 29 July] 1907 – 30 August 1946) was the leader of the Russian Fascist Party, which he led in exile from Manchuria. Rodzaevsky was also the chief editor of the RFP paper Nash Put'. After the defeat of anti-communist forces in the Russian Civil War, he and his followers fled to Manchuria in 1925. He was lured by the NKVD to return to the Soviet Union with false promises of immunity and executed in a Lubyanka prison cellar after a trial for "anti-Soviet and counter-revolutionary activities".

Early life

Konstantin Vladimirovich Rodzaevsky was born in a small town in the city of Blagoveshchensk, the administrative city of Amur Oblast on the 11th of August 1907. Konstantin's family was decidedly middle class and was a part of a quite rare and frail status of Siberian bourgeoise. Vladimir Ivanovich, his father, was a gentleman who worked as a notary with a degree in law. His mother, Nadezhda Mikhailovna was from an old Blagoveshchensk family and devoted herself to raising Konstantin alongside his younger brother, Vladimir, and his two sisters, Nadezhda and Nina. Most notably, Konstantin had at some point became a member of the Komsomol during his adolescence.[1]

Far Eastern Fascism

He fled the Soviet Union for Manchuria in 1925. In Harbin, Rodzaevsky entered the law academy and joined the Russian Fascist Organization. On May 26, 1931, he became the Secretary General of the newly created Russian Fascist Party; in 1934 the Party amalgamated with the All-Russian Fascist Organization of Anastasy Vonsyatsky, Rodzaevsky becoming its leader. He modeled himself on Benito Mussolini, and also used the Swastika as one of the symbols of the movement.

Rodzaevsky collected around himself personally selected bodyguards, using the symbolism of the former Russian Empire and Russian nationalist symbols; like the Italian Blackshirts, the Russian Fascists wore black uniforms with black crossed belts. Rodzaevsky's black shirts were armed with weapons obtained from the Imperial Japanese Army. They created an international organization of White émigrés with a central office in Harbin, the "Far East Moscow", and made connections in twenty-six nations around the world. The most important of these international posts were in New York City.

Manchukuo

Rodzaevsky had around 12,000 followers in Manchukuo. During the 2,600th anniversary of the founding of the Empire of Japan, Rodzaevsky, with a select group of people, paid his respects to Emperor Hirohito at the official celebration in the region.

The fascists installed a great swastika illuminated by neon light at their branch in Manzhouli (Manchouli), at least 3 km from the Soviet border. It was kept on all day and night to provide a show of power against the Soviet government. Rodzaevsky awaited the day when, leaving these signs on the Russian border, he would lead the White Anti-Soviet forces, joining White General Kislitsin and Japanese forces, into battle to "liberate the people of Russia from Soviet rule". Their main military acts involved the training of the Asano Detachment, an entirely ethnic-Russian special force in the Kwantung Army, organized for carrying out sabotage against Soviet forces in case of any Japanese invasion of Siberia. Japan was apparently interested in creating a White Russian regime in Russian Manchuria.

World War II and execution

During World War II, Rodzaevsky tried to launch an open struggle against Bolshevism, but Japanese authorities limited the RFP's activities to acts of sabotage in the Soviet Union. A notorious anti-Semite, Rodzaevsky published numerous articles in the party newspapers Our way and The Nation; he was also the author of the brochure "Judas’ End"[2] and the book "Contemporary Judaisation of the World or the Jewish Question in the 20th Century".[3]

At the end of the war, Rodzaevsky had what he called a "spiritual crisis". He claimed that Joseph Stalin's regime was evolving into a nationalist one. Rodzaevsky said he now understood that Stalinism was the ideal embodiment and realization of "our Russian fascism." In a long personal letter, he explained himself, made excuses, and admitted his mistakes. He admitted to participating in anti-Soviet activities, but said these were "acts against the motherland out of love for the motherland."[4] He said he was wrong to support Germany, but that he'd believed Hitler could help Russia by exterminating the Jews. The letter also showed striking similarities with the doctrines of National Bolshevism, with Rodzaevsky said he was now a "national Communist and convinced Stalinist":

I issued a call for an unknown leader, ... capable of overturning the Jewish government and creating a new Russia. I failed to see that, by the will of fate, of his own genius, and of millions of toilers, Comrade J.V. Stalin, the leader of the peoples, had become this unknown leader.

Rodzaevsky personally begged Stalin for forgiveness, referring to himself as "your unworthy slave".[4] In response, the Soviets offered him an amnesty and a job as a journalist in one of their newspapers. Rodzaevsky returned, only to be arrested upon arrival (along with fellow party-member Lev Okhotin). The trial, which began on August 26, 1946, was widely covered in the Soviet press. It was opened by the chairman of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union, Vasily Ulrikh. Rodzaevsky and other leaders of the RFP were charged with anti-Soviet agitation, creation of the Russian Fascist Party and distributing anti-Soviet propaganda among White army exiles and creation of similar anti-Soviet organizations in China, Europe and the United States. In addition, according to the verdict, he was involved in preparing an attack on the Soviet Union, together with a number of Japanese generals, as well as personally organizing spies and terrorist groups against the Soviet Union with the cooperation of German and Japanese intelligence. All of the defendants pleaded guilty.[5]

Rodzaevsky was sentenced to death. Also sentenced to various punishments were Grigory Semyonov, Vasilevsky Lev Fillipovich, Baksheev Aleksei Proklovich, Lev Okhotin, Ukhtomsky and others. Rodzaevsky was executed in a Lubyanka prison cellar on 30 August 1946.

In 2001, Rodzaevsky's final book, The Last Will of a Russian Fascist ("Zaveshchanie russkogo fashista"), was published in Russia. On 11 October 2010, due to a decision by the Central District Court of Krasnoyarsk, the book became recognized in Russia as extremist material, and has been included in the Federal List of Extremist Materials (No. 861).

References

- ↑ The Russian Fascists: Tragedy and Farce in Exile. 1925-1945 p.49

- ↑ Judas End Archived 2014-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Contemporary Judaisation of the World or the Jewish Question in the 20th Century Archived 2014-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Stephan, John J. (1978). The Russian Fascists: Tragedy and Farce in Exile, 1925-1945. Harper & Row. pp. 337–340. ISBN 978-0-06-014099-1.

- ↑ Center. archive of the FSB of the Russian Federation. Consequence case N-18765 in relation to G. M. Semenov, K. V. Rodzaevsky and others.

Notes

- The Russian Fascists: Tragedy and Farce in Exile, 1925-1945 by John J. Stephan ISBN 0-06-014099-2

- К. В. Родзаевский. Завещание Русского фашиста. М., ФЭРИ-В, 2001 ISBN 5-94138-010-0

- А.В. Окороков. Фашизм и русская эмиграция (1920-1945 гг.). М., Руссаки, 2002 ISBN 5-93347-063-5

- Knútr Benoit: Konstantin Rodzaevsky. Dict, 2012, ISBN 978-6-13841624-1

External links

- Inventory to the John J. Stephan Collection, 1932—1978

- Stephan, John J. (1978). The Russian Fascists: Tragedy and Farce in Exile, 1925-1945. Harper & Row. pp. 337–340. ISBN 978-0-06-014099-1.