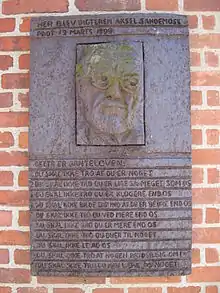

The Law of Jante (YAN-tuh, Danish: Janteloven [ˈjæntəˌlɔwˀən, -lɒwˀ-])[note 1] is a code of conduct[1] originating in fiction and now used colloquially to denote a social attitude of disapproval towards expressions of individuality and personal success.[2] Created by the Danish-Norwegian author Aksel Sandemose, it has also come to represent the egalitarian nature of Nordic countries.[3]

The "Law" was first formulated as ten rules in Sandemose's satirical novel A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks (En flyktning krysser sitt spor, 1933), but the attitudes themselves are older.[4] Sandemose portrays the fictional small Danish town of Jante, modelled upon his native town Nykøbing Mors in the 1930s where nobody was anonymous, a feature of life typical of small towns.[5]

Definition

There are ten rules in the law as defined by Sandemose, all expressive of variations on a single theme and usually referred to as a homogeneous unit: You are not to think you're anyone special, or that you're better than us.

The ten rules state:

- You're not to think you are anything special.

- You're not to think you are as good as we are.

- You're not to think you are smarter than we are.

- You're not to imagine yourself better than we are.

- You're not to think you know more than we do.

- You're not to think you are more important than we are.

- You're not to think you are good at anything.

- You're not to laugh at us.

- You're not to think anyone cares about you.

- You're not to think you can teach us anything.

The Janters who transgress this unwritten "law" are regarded with suspicion and some hostility, as it goes against the town's communal desire to preserve harmony, social stability and uniformity.

An eleventh rule recognized in the novel as "the penal code of Jante" is:

- Perhaps you don't think we know a few things about you?

From the chapter "Maybe you don't think I know something about you":

That one sentence (the eleventh rule), which acts as the penal code of Jante, as such was rich in content. It was an accusation of absolutely anything, and that it also had to be, because absolutely nothing was allowed. It was also an elaborate indictment, with all kinds of unspecified penalties given to be expected. Furthermore it was useful, depending fully on tone of voice, in financial extortion and enticement into criminal acts, and it could also be the best means of defense.

Sandemose's novel described working-class life in the fictional town of Jante. He wrote in 1955, a bit mischievously, that "Many people have recognized [in Jante] their own hometown – this has happened regularly to people from Arendal [Norway], Tromsø [Norway] and Viborg [Denmark]".[6] Sandemose made no claim to having invented the rules; he simply sought to formulate social norms that had stamped the Danish and Norwegian psyches for centuries.

Sociological effects

Although intended as criticism of society in general, some critics in the 1990s argued that the Law of Jante had shifted to refer to personal criticism of people who want to break out of their social groups and reach a higher position.[7]

It is common in Scandinavia to claim the Law of Jante as something quintessentially Danish, Norwegian or Swedish. The rules are treated as a way of behaving in order to fit in and results in dressing similarly and the types of cars that people buy and buying similar products for their homes.[8] It is commonly stated that Jante Law is for people in the provinces, but commentators have suggested that metropolitan areas are also affected.[8]

While the original intention was as satire, Kim Orlin Kantardjiev, a Norwegian politician[9] and educational advisor, claims that the Law of Jante is taught in schools as more of a social code to encourage group behavior, and attempts to credit it with fueling Nordic countries' high happiness scores.[8] It has also been suggested that contentedness with a humdrum lifestyle is a part of happiness in the Scandinavian countries.[10]

However, in Scandinavia, there have also been journalistic articles which link the Law of Jante to high suicide rates.[11] Backlash has occurred against the rules, and in Norway someone even placed a grave for Jante Laws, declaring them dead in 2005. However, others have questioned whether they will ever go away, as they may be firmly entrenched in society.[8]

Appearance in English-language sources

- When interviewed during episode 646 of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, broadcast November 9, 2018, Swedish actor Alexander Skarsgård explained that although he had recently received an Emmy and a Golden Globe Award for a lauded performance, the inhibitions induced by the Law of Jante prevented him from boasting of the accolade.[12]

- In Wisting, a 2019 Norwegian police procedural television series, partially in English, the character Line says (translated), "The newspaper sales numbers and the Law of Jante are merging."[13]

- In Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown, Bourdain and René Redzepi discuss Janteloven's effect on Danish culture.[14]

- In some interviews, Greta Thunberg credits and appreciates the law for her being ignored by Swedes that see her in public.[15][16]

See also

References

- ↑ "Your Guide to Norwegian Culture". discover-the-world.com. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ↑ Adleswärd, Viveka (2 November 2003). "Avundsjukan har urgamla anor" [Jealousy has ancient ancestry]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ Stephen, Trotter (2015-04-15). "Breaking the law of Jante" (PDF). University of Glasgow. eSharp. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

"the concept of Janteloven (the law of Jante) [is] a literary construct from Aksel Sandemose‟s A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks (1997[1933])... assumed to explain the egalitarian nature of the Scandinavian nations.

- ↑ Scott, Mark (18 December 2003). "Signs of Cracks in the Law of Jante". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-12-22.

Taken from a book by the Danish author Aksel Sandemose, the concept suggests that the culture within Scandinavian countries discourages people from promoting their own achievements over those of others.

- ↑ Translator note, En flygtning krydser sit spor, 2nd ed.

- ↑ English translation of passage from foreword of the Norwegian edition (1999), p. 14.

- ↑ Andersen, Steen (6 July 1992). "Den løbske Jantelov" [The Runaway Jante Law]. Morsø Folkeblad. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 BBC Ideas Forget hygge: The laws that really rule in Scandinavia

- ↑ Agenda Magasin online

- ↑ "The happiness of the Danes can easily be explained by 10 cultural rules". quartz. 29 September 2016.

- ↑ Klas Leffler in MittMedia Allehanda Västernorrland 2016-07-16

- ↑ Alexander Skarsgård Is Too Swedish To Be Cocky - YouTube The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, Published on 2018-11-10

- ↑ Wisting (TV series), Season 1, Episode 6, 30:38+

- ↑ "Transcripts: Anthony Bourdain Parts Unknown". CNN. October 6, 2013. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ↑ Hook, Leslie (31 March 2021). "Greta Thunberg: 'It just spiralled out of control'". Financial Times. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ↑ Henry, Grace (22 April 2021). "Greta Thunberg on the climate crisis: "You need to laugh sometimes"". Radio Times. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

Notes

Further reading

- Sandemose, Aksel (1933). En flyktning krysser sitt spor. Oslo: Aschehoug (Repr. 2005). ISBN 82-03-18914-8

- Sandemose, Aksel (1936). A fugitive crosses his tracks. translated by Eugene Gay-Tifft. New York: A.A. Knopf.

- Koldau, Linda Maria (2013): Jante Universitet. (Jante University). Vol. 1: Den skønne facade (The Beautiful Facade); Vol. 2: Uddannelseskatastrofen (Educational Disaster); Vol. 3: Totalitære strukturer (Totalitarian Structures). Hamburg: Tredition. ISBN 978-3-8495-0351-2 (Vol. 1); ISBN 978-3-8495-0350-5 (Vol. 2); ISBN 978-3-8495-0266-9 (Vol. 3). In Danish language.

- Koldau, Linda Maria (2013): Educational Disaster. The Destruction of Our Universities: The Danish Case. (abridged English version of Jante Universitet containing the most important analyses and a chapter on Jante Law mentality in Danish education). Hamburg: Tredition (forthcoming). ISBN 978-3-8495-4936-7. In English language.

- Steffen, Juliane (2011): "Hjem til Jante" (Home to Jante), concise analysis of the mechanisms of Jante Law at Danish universities, published in: Linda Maria Koldau: Jante Universitet. Vol. 2: Uddannelseskatastrofen. Hamburg: Tredition, 2013, pp. 464–466. ISBN 978-3-8495-0350-5 (Vol. 2). In Danish language.

Andersen, Steen: Nye forbindelser. Pejlinger i Aksel Sandemoses forfatterskab. Vordingborg: Attika, 2015. ISBN 978-87-7528-8700. In Danish Language.