| Flowering plant families (APG IV) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Early-diverging flowering plants | |||||

| Monocots: Alismatids • Commelinids • Lilioids | |||||

|

|

|||||

Eudicots

|

The nitrogen-fixing clade consists of four orders of flowering plants: Cucurbitales, Fabales, Fagales and Rosales.[lower-alpha 1] This subgroup, the COM clade and the order Zygophyllales constitute the fabids under the fourth Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG IV) system.[lower-alpha 2] The nitrogen-fixing clade encompasses 28 families of trees, shrubs, vines and herbaceous perennials and annuals. The roots of many of the species host bacteria that fix nitrogen into compounds the plants can use.[4][5]

The trees of this subgroup dominate many temperate forests.[6] Cannabis, with the psychoactive drug tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), has been used recreationally and ceremonially for at least 2400 years, but was in cultivation at least 6000 years before that for its oils and for making fabric and rope.[7] Cucumbers, melons and watermelons are cultivated around the globe.[8] The Mediterranean diet around 6000 years ago included fava beans, lentils, chickpeas and other legumes.[9] Chestnuts were spread throughout Europe by the ancient Romans.[10] The apple (in the rose family) is the second-most-cultivated sweet fruit, after the grape (in the order Vitales, not in this clade).[11]

Glossary

From the glossary of botanical terms:

- annual: a plant species that completes its life cycle within a single year or growing season

- basal: attached close to the base (of a plant or an evolutionary tree diagram)

- climber: a vine that leans on, twines around or clings to other plants for vertical support

- deciduous: falling seasonally, as with bark, leaves or petals

- herbaceous: not woody; usually green and soft in texture

- perennial: not an annual or biennial

- succulent (adjective): juicy or fleshy

- unisexual: of one sex; bearing only male or only female reproductive organs

- woody: hard and lignified; not herbaceous[12]

Families

| Family and a common name[6][lower-alpha 3] | Type genus and etymology[lower-alpha 4] | Total genera; global distribution | Description and uses | Order[6] | Type genus images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anisophylleaceae (leechwood family) | Anisophyllea, from Greek for "unequal leaves"[15][16] | 4 genera, mainly in the tropics[17][18] | Shrubs and trees with unisexual flowers. Anisophyllea griffithii is sometimes harvested for timber.[15][19] | Cucurbitales[15] | |

| Apodanthaceae (stemsucker family) | Apodanthes, from Greek for "stalkless flowers"[20][21] | 2 genera, scattered worldwide[22][23] | Parasitic plants lacking chlorophyll. Typically, only the flowers are visible on the host's bark.[19][22] | Cucurbitales[22] | |

| Barbeyaceae (elm-olive family) | Barbeya, for William Barbey (1842–1914)[24] | 1 genus, in forested slopes on either side of the Gulf of Aden[24][25] | Unisexual trees[24][26] | Rosales[24] | — |

| Begoniaceae (begonia family) | Begonia, for Michel Bégon (1638–1710), a French official and plant collector[27][28] | 2 genera, mainly throughout the tropics, extending into the subtropics[17][29] | Mostly perennial herbaceous succulents with unisexual flowers, with a few subshrubs and herbaceous plants up to 4 m (13 ft) tall. Some species grow on rocks, some on other plants. Many species are popular potted-plant ornamentals.[19][27] | Cucurbitales[27] | |

| Betulaceae (birch family) | Betula, from a Latin plant name[30][31][32] | 6 genera, in the Northern Hemisphere and parts of South America and Southeast Asia[33][34] | Deciduous shrubs and trees with unisexual flowers and loose bark, usually with lenticels, horizontal ruptures that allow gas exchange. The wood of birch and alder is used to make furniture and musical instruments.[19][33] | Fagales[33] | |

| Cannabaceae (hemp family) | Cannabis, from a Latin plant name[35][36] | 9 genera, scattered worldwide[7][37] | Shrubs, trees, vines and herbaceous plants with thin sap. Beer hops have been in cultivation since the 1200s.[7][38] | Rosales[7] | |

| Casuarinaceae (she-oak family) | Casuarina, from a Malaysian word for cassowary[39][40][41] | 4 genera, in parts of Oceania, Southeast Asia and Madagascar[39][42] | Evergreen trees and shrubs, unisexual or with unisexual flowers, with green branchlets and reduced leaves. Casuarina equisetifolia is planted to anchor beach sand.[26][39] | Fagales[39] | |

| Coriariaceae (tanner-bush family) | Coriaria, from Latin for "leather"[43][44] | 1 genus, scattered worldwide[17][45] | Shrubs and slightly woody herbaceous plants with nitrogen-fixing roots. The fruits are used for dyes. Most species are poisonous.[19][46] | Cucurbitales[46] | |

| Corynocarpaceae (cribwood family) | Corynocarpus, from Greek for "club fruit"[47] | 1 genus, mostly in the southwestern Pacific[17][48] | Evergreen trees and big shrubs. The trees have been used to construct canoes.[49] | Cucurbitales[49] | |

| Cucurbitaceae (cucumber family) | Cucurbita, from a Latin plant name[50][51][52] | 101 genera, worldwide, especially in the tropics[17][53] | Herbaceous and woody perennials, mostly vines. Butternut squash was domesticated in the Peruvian Andes over 9000 years ago. Cucumbers were cultivated in ancient Ur.[8][19] | Cucurbitales[8] | |

| Datiscaceae (durango-root family) | Datisca, from a Latin plant name[54][55] | 1 genus, in central and southwest Asia, in and near California, and around the Mediterranean[17][56] | Mostly unisexual herbaceous perennials with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. D. cannabina has been used as a dye in Asia.[57] | Cucurbitales[57] | |

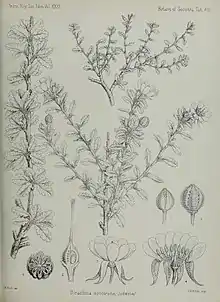

| Dirachmaceae (rachman family) | Dirachma, from a Socotran plant name, possibly[24] | 1 genus, in Socotra and Somalia[58][59] | Trees and shrubs[24] | Rosales[24] |  Dirachma socotrana |

| Elaeagnaceae (oleaster family) | Elaeagnus, from a Greek plant name[60][61][62] | 3 genera, mostly in the Northern Hemisphere, Southeast Asia and Queensland, Australia[58][63] | Small trees and shrubs. Several species of Elaeagnus are cultivated as ornamentals. Hippophae rhamnoides has been used in jams and juices for centuries. The roots are generally nitrogen-fixing.[64] | Rosales[64] | |

| Fabaceae (pea family) | Vicia. Faba, an earlier synonym, is from a Latin plant name.[9][65][66] | 780 genera, scattered worldwide[9][67] | Also known as legumes. Trees, shrubs, vines and herbaceous plants. The roots are generally nitrogen-fixing. Staple foods include soybeans, peanuts, peas and various beans. Some species provide valuable gums, soaps and perfumes.[9][19] | Fabales[9] | |

| Fagaceae (beech family) | Fagus, from a Latin plant name[68][69][70] | 8 genera, scattered in the tropics and the temperate Northern Hemisphere[10][71] | Mainly trees with unisexual flowers. Edible chestnuts have been cultivated for thousands of years. Cork is harvested mainly from the cork oak. Wood from beech and oak trees is used in construction and carpentry.[10][19] | Fagales[10] | |

| Juglandaceae (walnut family) | Juglans, from a Latin plant name[72][73][74] | 9 genera, mostly in parts of the Americas, Asia and Oceania.[75][76] | Shrubs and trees, mostly with unisexual flowers. Trees with edible nuts include walnuts and pecans.[19][75] | Fagales[75] | |

| Moraceae (mulberry family) | Morus, from a Latin plant name[77][78][79] | 48 genera, scattered worldwide[80][81] | Shrubs, trees, climbers and herbaceous perennials, frequently with whitish sap. Some grow on other plants. The common fig was most likely already in cultivation more than 11,000 years ago. Breadfruit is a food crop in parts of Asia and the Pacific.[38][80] | Rosales[80] | |

| Myricaceae (bayberry family) | Myrica, from a Greek plant name[82][83][84] | 3 genera, scattered worldwide[85][86] | Evergreen shrubs and small trees, unisexual or with unisexual flowers. The roots are usually nitrogen-fixing. Chinese bayberry is grown commercially in China for its fruit.[38][85] | Fagales[85] | |

| Nothofagaceae (roble family) | Nothofagus, from Greek for "false", plus Fagus[87][88] | 1 genus, in Oceania and southern South America[89][90] | Shrubs and trees with unisexual flowers. The timber is used in carpentry.[89] | Fagales[89] | |

| Polygalaceae (milkwort family) | Polygala, from Greek and Latin plant names[91][92][93] | 30 genera, scattered widely, except in polar regions[94][95] | Herbaceous plants, vines, shrubs and trees, some up to 50 m (160 ft) tall.[26][96] | Fabales[96] | |

| Quillajaceae (soapbark-tree family) | Quillaja, from a Chilean plant name[97] | 1 genus, in warmer regions of temperate South America[94][98] | Evergreen trees with leathery leaves and foamy saponins in their bark[99] | Fabales[99] | |

| Rhamnaceae (buckthorn family) | Rhamnus, from Greek and Latin plant names[100][101][102] | 63 genera, worldwide[58][103] | Deciduous shrubs and trees, for the most part. Ziziphus jujuba and Z. mauritiana, similar to dates, are commercially grown.[104][105] | Rosales[105] | |

| Rosaceae (rose family) | Rosa, from a Latin plant name[106][107][108] | 110 genera, worldwide[58][109] | Trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants, frequently with spiny branches. The genus Rubus includes raspberries and blackberries. Prunus includes plums, peaches, cherries and almonds; domesticated almonds are found in Bronze Age archaeological sites in the Eastern Mediterranean.[11][38] | Rosales[11] | |

| Surianaceae (bay-cedar family) | Suriana, for Joseph Donat Surian (1650–1691), a French doctor, chemist and botanist[110][111] | 5 genera, scattered worldwide in tropical, subtropical and warm-temperate zones[94][112] | Shrubs and trees[113] | Fabales[113] | |

| Tetramelaceae (false hemp-tree family) | Tetrameles, from Greek for "four-part" (sepals)[114][115] | 2 genera, in parts of Oceania and South and Southeast Asia[114][116] | Tall unisexual trees with soft wood[114] | Cucurbitales[114] | |

| Ticodendraceae (tico-tree family) | Ticodendron, from Tico plus Greek for "tree"[117] | 1 genus, in Central America and Mexico[117][118] | Just one species of unisexual evergreen trees[19][117] | Fagales[117] | |

| Ulmaceae (elm family) | Ulmus, from a Latin plant name[119][120][121] | 7 genera, mainly in the temperate Northern Hemisphere[122][123] | Trees and shrubs with thin sap. Dutch elm disease killed almost all of the elms in North America and Europe in the 20th century. Disease-resistant elms have been difficult to propagate.[19][122] | Rosales[122] | |

| Urticaceae (nettle family) | Urtica, from a Latin plant name[124][125] | 60 genera, worldwide[126][127] | Shrubs, trees, woody vines and herbaceous plants, some growing on other plants, and some with stinging hairs. Ramie (Boehmeria nivea) is grown in East Asia for its long, strong fibrous stalks.[126][128] | Rosales[126] | |

See also

Notes

- ↑ The taxonomy (classification) in this list follows Plants of the World (2017)[1] and the fourth Angiosperm Phylogeny Group system.[2] Total counts of genera for each family come from Plants of the World Online (POWO).[3] (See the POWO license.) Extinct taxa are not included. A clade of flowering plants is a subgroup consisting of all the descendants of a theoretical ancient ancestor.

- ↑ APG IV does not assign a name to the nitrogen-fixing clade.[2][4]

- ↑ Each family's formal name ends in the Latin suffix -aceae and is derived from the name of a genus that is or once was part of the family.[14]

- ↑ Some plants were named for naturalists (unless otherwise noted).

Citations

- ↑ Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017.

- 1 2 Angiosperm Phylogeny Group 2016.

- ↑ POWO.

- 1 2 Stevens 2023, Summary of APG IV.

- ↑ Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 10, 248–292.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 248–292.

- 1 2 3 4 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 272–273.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 286–289.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 249–259.

- 1 2 3 4 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 277–278.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 262–267.

- ↑ Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 638–670.

- ↑ Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 10.

- ↑ ICN, art. 18.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 284.

- ↑ USDA, Anisophylleaceae, Type.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kubitzki 2011, p. 4.

- ↑ POWO, Anisophylleaceae.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 POWO, Neotropikey.

- ↑ Quattrocchi 2000, p. 175.

- ↑ IPNI, Apodanthaceae, Type.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 283.

- ↑ POWO, Apodanthaceae.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 268.

- ↑ POWO, Barbeyaceae.

- 1 2 3 POWO, Flora of Somalia.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 291–292.

- ↑ IPNI, Begoniaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Begoniaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 64.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 66.

- ↑ IPNI, Betulaceae, Type.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 282.

- ↑ POWO, Betulaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 80.

- ↑ IPNI, Cannabaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Cannabaceae.

- 1 2 3 4 POWO, Flora of Tropical East Africa.

- 1 2 3 4 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 280–281.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 85.

- ↑ IPNI, Casuarinaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Casuarinaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 104.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 104.

- ↑ POWO, Coriariaceae.

- 1 2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 285–286.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 105.

- ↑ POWO, Corynocarpaceae.

- 1 2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 284–285.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 108.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 113.

- ↑ IPNI, Cucurbitaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Cucurbitaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 114.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 120.

- ↑ POWO, Datiscaceae.

- 1 2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 290–291.

- 1 2 3 4 Kubitzki 2004, p. 2.

- ↑ POWO, Dirachmaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 129.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 131.

- ↑ IPNI, Elaeagnaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Elaeagnaceae.

- 1 2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 269.

- ↑ IPNI, Fabaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Faba.

- ↑ POWO, Fabaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 138.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 141.

- ↑ IPNI, Fagaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Fagaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 179.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 180.

- ↑ IPNI, Juglandaceae, Type.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 279–280.

- ↑ POWO, Juglandaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 211.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 210.

- ↑ IPNI, Moraceae, Type.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 273–274.

- ↑ POWO, Moraceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 214.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 211.

- ↑ IPNI, Myricaceae, Type.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 278–278.

- ↑ POWO, Myricaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 219.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 215.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 276–277.

- ↑ POWO, Nothofagaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 245.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 239.

- ↑ IPNI, Polygalaceae, Type.

- 1 2 3 Kubitzki 2007, p. 5.

- ↑ POWO, Polygalaceae.

- 1 2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 261–262.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 254.

- ↑ POWO, Quillajaceae.

- 1 2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 248.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 257.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 252.

- ↑ IPNI, Rhamnaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Rhamnaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Flora of Zambesiaca.

- 1 2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 269–271.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 261.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 257.

- ↑ IPNI, Rosaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Rosaceae.

- ↑ Burkhardt 2018, p. S-108.

- ↑ IPNI, Surianaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Surianaceae.

- 1 2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 260.

- 1 2 3 4 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 289–290.

- ↑ USDA, Tetramelaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Tetramelaceae.

- 1 2 3 4 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 281.

- ↑ POWO, Ticodendraceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 302.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 296.

- ↑ IPNI, Ulmaceae, Type.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 271–272.

- ↑ POWO, Ulmaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 304.

- ↑ IPNI, Urticaceae, Type.

- 1 2 3 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 275–276.

- ↑ POWO, Urticaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Flora of West Tropical Africa.

References

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2016). "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 181 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1111/boj.12385.

- Burkhardt, Lotte (2018). Verzeichnis eponymischer Pflanzennamen – Erweiterte Edition [Index of Eponymic Plant Names – Extended Edition] (pdf) (in German). Berlin: Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum, Freie Universität Berlin. doi:10.3372/epolist2018. ISBN 978-3-946292-26-5. S2CID 187926901. Retrieved January 1, 2021. See the Creative Commons license.

- Christenhusz, Maarten; Fay, Michael Francis; Chase, Mark Wayne (2017). Plants of the World: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Vascular Plants. Chicago, Illinois: Kew Publishing and The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-52292-0.

- Coombes, Allen J. (2012). The A to Z of Plant Names: A Quick Reference Guide to 4000 Garden Plants. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-1-60469-196-2.

- IPNI (2022). "International Plant Names Index". London, Boston and Canberra: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; and the Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved December 20, 2022.

- Kubitzki, K. (2004). "Introduction to Families Treated in This Volume". In Kubitzki, K. (ed.). Celastrales, Oxalidales, Rosales, Cornales, Ericales. Vol. VI. Berlin: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 2. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-07257-8. ISBN 978-3-662-07257-8. S2CID 12809916.

- Kubitzki, K. (2007). "Introduction to the Groups Treated in This Volume". In Kubitzki, K. (ed.). Berberidopsidales, Buxales, Crossosomatales, Fabales p.p., Geraniales, Gunnerales, Myrtales p.p., Proteales, Saxifragales, Vitales, Zygophyllales, Clusiaceae Alliance, Passifloraceae Alliance, Dilleniaceae, Huaceae, Picramniaceae, Sabiaceae. Vol. IX. Berlin: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 5. ISBN 978-3-540-32214-6.

- Kubitzki, K. (2011). "Introduction to Cucurbitales". In Kubitzki, K. (ed.). Flowering Plants. Eudicots: Sapindales, Cucurbitales, Myrtaceae. The families and genera of vascular plants. Vol. X. Berlin: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 4. ISBN 978-3-642-14397-7.

- POWO (2019). "Plants of the World Online". London: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved January 1, 2023. See their terms-of-use license.

- Quattrocchi, Umberto (2000). CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names, Volume I, A–C. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-2675-2.

- Stearn, William (2002). Stearn's Dictionary of Plant Names for Gardeners. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-36469-5.

- Stevens, P.F. (2023) [2001]. "Angiosperm Phylogeny Website". Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- Turland, N. J.; et al. (eds.). International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China, July 2017 (electronic ed.). Glashütten: International Association for Plant Taxonomy. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- "USDA, Agricultural Research Service, National Plant Germplasm System". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN Taxonomy). Beltsville, Maryland: National Germplasm Resources Laboratory. 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2022.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_-_Utsira%252C_Norway_2021-08-06.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)