| Northern Qiang | |

|---|---|

| Rrmearr | |

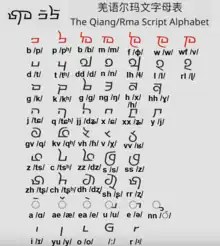

Rma Script used in Qiang Language | |

| Pronunciation | [ʐmeʐ] |

| Native to | China |

| Region | Sichuan Province |

| Ethnicity | Qiang people |

Native speakers | (58,000 cited 1999)[1] |

| Latin, Rma | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | cng |

| Glottolog | nort2722 Northern Qiangsout3257 Southeast Maoxian Qiang |

| ELP | Northern Qiang |

Northern Qiang is a Sino-Tibetan language of the Qiangic branch, more specifically falling under the Tibeto-Burman family. It is spoken by approximately 60,000 people in East Tibet, and in north-central Sichuan Province, China.

Unlike its close relative Southern Qiang, Northern Qiang is not a tonal language.

Northern Qiang dialects

Northern Qiang is composed of several different dialects, many of which are easily mutually intelligible. Sun Hongkai in his book on Qiang in 1981 divides Northern Qiang into the following dialects: Luhua, Mawo, Zhimulin, Weigu, and Yadu. These dialects are located in Heishui County as well as the northern part of Mao County. The Luhua, Mawo, Zhimulin, and Weigu varieties of Northern Qiang are spoken by the Heishui Tibetans. The Mawo dialect is considered to be the prestige dialect by the Heishui Tibetans.

Names seen in the older literature for Northern Qiang dialects include Dzorgai (Sifan), Kortsè (Sifan), Krehchuh, and Thóchú/Thotcu/Thotśu. The last is a place name.[2]

Sims (2016)[3] characterizes Northern (Upstream) Qiang as the *nu- innovation group. Individual dialects are highlighted in italics.

- Northern Qiang

- NW Heishui: Luhua 芦花镇

- Central Heishui

- Qinglang 晴朗乡

- Zhawo 扎窝乡

- Ciba 慈坝乡

- Shuangliusuo 双溜索乡

- uvular V's innovation group: Zhimulin 知木林乡, Hongyan 红岩乡, Mawo 麻窝乡

- SE Heishui: Luoduo 洛多乡, Longba 龙坝乡, Musu 木苏乡, Shidiaolou 石碉楼乡

- North Maoxian: Taiping 太平乡, Songpinggou 松坪沟乡

- South Songpan: Xiaoxing 小姓乡, Zhenjiangguan 镇江关乡, Zhenping 镇坪乡

- West Maoxian / South Heishui: Weigu 维古乡, Waboliangzi 瓦钵乡梁子, Se'ergu 色尔古镇, Ekou, Weicheng 维城乡, Ronghong, Chibusu, Qugu 曲谷乡, Wadi 洼底乡, Baixi 白溪乡, Huilong 回龙乡, Sanlong 三龙乡

- Central Maoxian: Heihu 黑虎乡

- SE Maoxian (reflexive marker innovation): Goukou 沟口乡, Yonghe 永和乡

Phonology

The phonemic inventory of the Northern Qiang of Ronghong village consists of 37 consonants, and eight basic vowel qualities.[4]: 22, 25 The syllable structure of Northern Qiang allows up to six sounds.[4]: 30

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||||

| Stop/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | ts | ʈʂ | tɕ | k | q | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | tsʰ | ʈʂʰ | tɕʰ | kʰ | qʰ | ||

| voiced | b | d | dz | ɖʐ | dʑ | ɡ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | ɸ | ɬ | s | ʂ | ɕ | x | χ | h |

| voiced | z | ʐ | ʁ | ɦ | |||||

| Approximant | l | [j] | [w] | ||||||

- A glottal stop [ʔ] may be heard in word-initial position when preceding vowels.

- /ɸ/ can also be heard as a labio-dental [f].

- /ʐ/ can also be heard as an alveolar [ɹ].

- /ɕ x/ can have voiced allophones of [ʑ ɣ].

- Approximants [w j] are not distinct from /i u/ but are transcribed in intervocalic position, and initially /i u/, to clarify syllable division.

Vowels

Northern Qiang distinguishes between unstressed and long vowels (signified by two small dots, "ː") for all of its vowels except for /ə/ . In addition, there exist 15 diphthongs and one triphthong in the language of Northern Qiang.[4]: 25–26

| Front | Mid | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i, iː y, yː | u, uː | |

| Mid | e, eː | ə | o, oː |

| Low | a, aː | ɑ, ɑː |

There may not be a significant phonetic difference in sound between /i/ and /e/, and /u/ and /o/, respectively. In fact, they are often used in place of one another without changing the meaning.

Diphthongs and triphthongs

Diphthongs: ia, iɑ, ie, ye, eu, əu, ei, əi, oi, uɑ, ua, uə, ue, ui, ya

Triphthong: uəi[4]: 26

R-coloring

As the Northern Qiang language becomes more endangered, the use of r-coloring is not being passed down to younger generations of the Northern Qiang people. As a result, there is great variation in its use. R-coloring is not considered its own phoneme because it is a vowel feature and only used to produce vowel harmony (see below), most commonly signifying a first person plural marking.[4]: 28

- Example: miʴwu [person (<mi):all] 'all the people'[4]: 28

Syllable structure

The following is the Northern Qiang Syllable prototype structure. All are optional apart from the central vowel (underlined):[4]: 30

(The final 'fricative' may be a fricative F, an affricate ᴾF, or /l/.)

All consonants occur as initials, though /ŋ/ only before /u/, and /ɦ/ only in a directional prefix and in a filler interjection. Almost all apart from the aspirated consonants occur as finals. These do not preserve Proto-Tibeto-Burman finals, which have all been lost, but are the result of the reduction of unstressed syllables (e.g. [səf] 'tree' from /sə/ 'wood' + /pʰə/ 'forest').

Initial FC clusters may be:

- /ʂ/ + /p t tɕ k q b d dʑ ɡ m/,

- /x/ + /tɕ tʂ k s ʂ ɬ l dʑ dʐ z ʐ/,

- /χ/ + /tʂ q s ʂ ɬ l d dʑ dʐ z ʐ n/

The fricatives are voiced to [ʐ ɣ ʁ] before a voiced consonant. In addition, /ʂ/ > [s z] before /t d/ and > [ɕ ʑ] before /pi pe bi tɕ dʑ/.

In final CᴾF clusters, the C is a fricative. Clusters include /ɕtɕ xʂ xtʂ xɬ ɣz ɣl χs/.

| Template | Qiang Word | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| V | ɑ | 'one' |

| VG | ɑu | 'one pile' |

| GV | wə | 'bird' |

| VC | ɑs | 'one day' |

| VCF | əχʂ | 'tight' |

| CV | pə | 'buy' |

| CGV | kʰuə | 'dog' |

| CGVG | kuɑi-tʰɑ | 'strange' |

| CVC | pɑq | 'intererst' |

| CVCF | bəxʂ | 'honey' |

| CGVC | duɑp | 'thigh' |

| FCV | xtʂe | 'louse' |

| FCGV | ʂkue | 'roast' |

| FCGVG | ʂkuəi | 'mt. goat' |

| FCVC | ʂpəl | 'kidney' |

| FCVCF | ʂpəχs | 'Chibusu' |

| FCGVC | ʂquɑp | 'quiet' |

| FCGVCF | ɕpiexɬ | 'scar' |

Phonological processes

Initial weakening

When a compound or a directional prefix is added before an aspirated initial, the latter becomes the final of the preceding syllable in the new word. This typically causes it to lose its aspiration.[4]: 31–32

- Example: tə- DIR + ba 'big' > təwa 'become big'[4]: 32

Vowel harmony

Vowel harmony exists in the Mawo (麻窝) dialect. Typically, vowel harmony is used to match a preceding syllable's vowel with the succeeding vowel or its height. In some cases, however, the vowel of a succeeding syllable will harmonize in the opposite way, matching with the preceding vowel. This process occurs across syllables in compounds or in prefix + root combinations. Vowel harmony can also occur for r-coloring on the first syllable if the second syllable of a compound or prefix + root combination already has r-coloring.[4]: 35–36

- Example: wə 'bird' + ʂpu 'flock' > wuʂpu '(wild) pigeon'[4]: 35

- Example: Chinese zhàogù + Qiang pə 'to do' > tʂɑuku-pu 'take care of'[4]: 36

- Example: me 'not' + weʴ 'reduce' > meʴ-weʴ 'unceasingly'[4]: 35

- Example: The realization of the word "one" (a) is influenced by the classifiers:[5]

- e si (a day)

- a qep (a can)

- ɑ pɑu (a packet)

- o ʁu (a barrel)

- ɘ ʑu (a pile)

- ø dy (a mouth)

Epenthetic vowel

The vowel /ə/ can be embedded within a collection of consonants that are restricted by the syllable canon. The epenthetic vowel is used to combine sounds that would typically be impermissible.[4]: 36

- Example: bəl-əs-je [do-NOM (< -s)-good to eat] 'advantageous'[4]: 36

Free variation

For some words, changing or adding consonants produces no phonological difference in meaning. The most common consonant interchange is between /ʂ/ and /χ/.[4]: 37

Orthography

| Letter | a | ae | b | bb | c | ch | d | dd | dh | e | ea | f | g | gg | gv | h | hh | hv | i | iu | j | jj | k | kv | l |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | a | æ | p | b | t͡sʰ | ʈ͡ʂʰ | t | d | ɖ͡ʐ | ə | e | f | k | g | q | x | ɣ | h | i | y | t͡ɕ | d͡ʑ | kʰ | qʰ | l |

| Letter | lh | m | n | ng | ny | o | p | ph | q | rr | s | sh | ss | t | u | v | vh | vv | w | x | xx | y | z | zh | zz |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | ɬ | m | n | ŋ | ȵ | o | pʰ | ɸ | t͡ɕʰ | ʐ | s | ʂ | z | tʰ | u | χ | ɦ | ʁ | w, u̥ | ɕ | ʑ | j | t͡s | ʈ͡ʂ | d͡z |

Nasalized vowels are indicated with trailing nn, rhotacized vowels are indicated with trailing r, long vowels are indicated by doubling the vowel letter.

Morphology

Northern Qiang uses affixes in the form of prefixes and suffixes to describe or modify the meaning of nouns and verbs.[4]: 39, 43, 120 Other morphological processes that are affixed include gender marking, marking of genitive case, compounding, and nominalization. Northern Qiang also uses non-affixational processes such as reduplication.[4]: 39

Noun phrase

In Northern Qiang, any combination of the following order is allowed as long as it follows this flow. Some of the items found below, such as adjectives, may be used twice within the same noun phrase.[4]: 39

Northern Qiang noun phrase structure

GEN phrase + Rel. clause + Noun + ADJ + DEM/DEF + (NUM + CL)/PL[4]: 39

Gender marking

Gender marking only occurs in animals. Typically, /mi/ is the suffix for females, while /zdu/ is the suffix for males.[4]: 48

Pronouns

Northern Qiang pronouns can be represented from the 1st, 2nd, or 3rd person, and can refer to one, two, or more than two people.[4]: 50

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | qɑ | tɕi-zzi | tɕi-le |

| 2 | ʔũ | ʔi-zzi | ʔi-le |

| 3 | theː / qupu | thi-zzi | them-le |

Genitive case

The genitive marker /-tɕ(ə)/ is placed on the modifying noun; this modifying noun will precede the noun it modifies.[4]: 99–100

Verbal morphology

The meaning of verbs can be changed using prefixes and suffixes, or by using reduplication.[4]: 120, 123

| Marking in Qiang | Purpose/Meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | intensifying adverb | |

| 2 | "various" | direction/orientation, or 3rd person indirect directive |

| 3 | /mə-/, or /tɕə-/ | simple negation, or prohibitive |

| 4 | /tɕi/ | continuative aspect |

| Marking in Qiang | Purpose/Meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | /-ʐ/ | causative |

| 6 | /-ɑː/ | prospective aspect |

| 7 | /kə/ or /lə/ | '(to) go', or '(to) come' (auxiliary directional verbs) |

| 8 | /-jə/ | repetition |

| 9 | /-ji/ | change of state |

| 10 | /-l-/ | 1st person indirect directive |

| 11 | /-k/ | inferential evidential, mirative |

| 12 | /-u/ | visual evidential |

| 13 | /-ʂɑ/, /-sɑn/, /-ʂəʴ/, /-sɑi/, [-wu/ ~ -u] | non-actor person (1sg, 2sg, 1pl, 2pl, 3sg/pl) |

| 14 | /-ɑ/, /-n/, /-əʴ/, /-i/, /-tɕi/ | actor person (1sg, 2sg, 1pl, 2pl, 3pl) |

| 15 | /-i/ | hearsay evidential |

Reduplication

Repetition of the same root verb signifies a reciprocal action upon one actors, or an ongoing action.[4]: 52, 123

- Example: mɑ 'plaster (a wall)' > məmɑ 'be plastering'[4]: 123

Other morphological processes

Compounding

In Northern Qiang, the modifying noun of the compound must precede the modified noun.[4]: 43

khuɑ-ʁl

dog-child

'puppy'[4]: 48, 49

Nominalization

Nouns are created from adjectives or verbs using clitics /-s/, /-m/, or /-tɕ/, the indefinite markers /le/ or /te/, or the definite marker /ke/.[4]: 59, 223

Syntax

The Northern Qiang language has quite a predictable syntax without many variations. The typical basic word order is subject–object–verb (SOV).[4]: 221 Northern Qiang borrows some Mandarin Chinese words and phrases.[4]: 222

Clause structure

Order

(TEMP) (LOC) (ACTOR) (GOAL/RECIPIENT) (ADV) (UG) VC (PART)[4]: 221

(TEMP = temporal phrase; UG = undergoer; VC = verb complex; PART = clause-final particle)

A sentence in Northern Qiang may be as short as a verb complex, which may just be a predicate noun.[4]: 222

As shown from the order stated above, Northern Qiang is a language with a SOV sentence structure.

Code mixing

Many loan words or loan phrases from Mandarin are borrowed, but the word order of these phrases is rearranged to fit the grammatical structure of Northern Qiang.[4]: 222

pəs-ŋuəɳi

today-TOP

ʐmətʂi-sətsim-leː

emperor-wife-DEF:CL

tɕiutɕin

(after.all

ʂə

be)

mi-leː

person-DEF:CL

ŋuə-ŋuɑ?

COP-Q

'Today, is the emperor's wife a human?'[4]: 222

In this sentence, the words "tɕiutɕin" and "ʂə" are borrowed from Mandarin.

Status

As with many Qiangic languages, Northern Qiang is becoming increasingly threatened.[6] Because the education system largely uses Standard Chinese as a medium of instruction for the Qiang people, and as a result of the universal access to schooling and television, most Qiang children are fluent or even monolingual in Chinese while an increasing percentage cannot speak Qiang.[7] Much of the population marry people from other parts of China who only speak Mandarin.[4]: 12

See also

References

- ↑ Northern Qiang at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ↑ Sun, Jackson T.-S. (1992). "Review of Zangmianyu Yuyin He Cihui "Tibeto-Burman Phonology and Lexicon"" (PDF). Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 15 (2): 76–77.

- ↑ Sims, Nathaniel (2016). "Towards a More Comprehensive Understanding of Qiang Dialectology" (PDF). Language and Linguistics. 17 (3): 351–381. doi:10.1177/1606822X15586685.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 LaPolla (2003)

- ↑ Sun, Hongkai 孙宏开 (1981). Qiāngyǔ jiǎnzhì 羌语简志 (in Chinese). Minzu chubanshe.

- ↑ "Qiang, Southern". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2019-03-17.

- ↑ LaPolla (2003), p. 5

Bibliography

- Bradley, David (1997). "Tibeto-Burman Languages and Classification" (PDF). In Bradley, D. (ed.). Papers in South East Asian Linguistics No. 14: Tibeto-Burman Languages of the Himalayas. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 1–72. ISBN 0-85883-456-1.

- LaPolla, Randy (2003). A Grammar of Qiang: With Annotated Texts and Glossary. with Chenglong Huang. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017829-X.

- Evans, Jonathan P. (2006). "Vowel Quality in Hongyan Qiang" (PDF). Language and Linguistics. 7 (4): 937–960.