French Popular Party Parti populaire français | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official Leader | Jacques Doriot |

| General Secretary | Victor Barthélemy |

| Founded | June 28, 1936 |

| Dissolved | February 22, 1945 |

| Headquarters | Paris, France |

| Newspaper | L'Émancipation nationale Le Cri du Peuple |

| Youth wing | Jeunesse Populaire Française |

| Armed wing | Service d'Ordre |

| Membership (1937) | 120,000 |

| Ideology | French fascism |

| Political position | Far-right |

| National affiliation | Freedom Front (1937–1938) |

| Colours | Blue, red, white |

| Party flag | |

Other Flags: | |

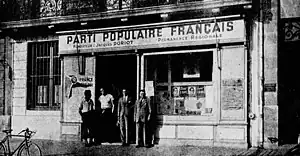

The French Popular Party (French: Parti populaire français) was a French fascist and anti-semitic political party led by Jacques Doriot before and during World War II. It is generally regarded as the most collaborationist party of France.

Formation and early years

The party was formed on 28 June 1936, by Doriot and a number of fellow former members of the French Communist Party (including Henri Barbé and Paul Marion) who had moved towards nationalism in opposition to the Popular Front. The PPF centered initially around the town of Saint-Denis, of which Doriot was mayor (as a Communist) from 1930 to 1934, and drew its support from the large working class population in the area. Although not avowedly nationalistic at this point, the PPF adopted many aspects of social nationalist politics, imagery and ideology, and quickly became popular among other nationalists, attracting to its ranks former members of such groups as Action Française, Jeunesses Patriotes, Croix de Feu and Solidarité Française. The party held a number of large rallies following their formation and adopted as the party flag a Celtic cross against a red, white and blue background. Members wore light blue shirts, dark blue trousers, berets and armbands bearing the party symbol as a uniform, although the uniform was not as ubiquitous as in other far-right movements.

Despite the Communist origins of much of its leadership (which retained the name Politburo), the party was virulently anti-Marxist, which it came to regard as a Jewish pseudo-socialism which was not working for real improvements to the situation of the French working-classes. Physical violence by PPF members (especially the PPF paramilitary wing, the Service d'Ordre) against Communist Party supporters and other perceived enemies was not uncommon. The PPF, in its initial, working class, phase, was economically populist and anti-banking. It moved closer to corporatism in 1937 when Doriot was deserted by his traditional working class base in losing the mayoral election in Saint-Denis, and the party began receiving financial support from right-wing leaders of business and finance, such as the General Manager of the Banque Worms, Gabriel Leroy-Ladurie.

Doriot proposed to Colonel François de La Rocque uniting his Parti Social Français with the PPF to form an anti-Marxist alliance to be called the Front de la Liberté, but La Rocque, who was a capitalist, rejected the movement. That same year, the PPF contacted the Italian government of Benito Mussolini to request support. According to the private diary of Count Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini's foreign minister and son-in-law: "Doriot's right-hand-man has asked me to continue to pay subsidies and provide weapons. He envisages a winter filled with conflicts. (Ciano diary, Sept. 1937).[1] Ciano paid 300 000 francs from the coffers of Fascist Italy to Victor Arrighi (head of the Algiers section of the PPF).

These funds from the Italian Fascists and French banking and business interests were used to purchase a number of newspapers, including La Liberté, which became the official party organ. In time, as the Nazi regime began to contribute a greater share of the PPF's funds, it began to advocate corporatism, and pushed for closer ties with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in a grand alliance against the Soviet Union.[2]

Ideology and fascism of PPF

The PPF's ardent advocacy of collaboration with the Nazis was accompanied, somewhat discordantly, with nationalistic rhetoric. Members of the PPF were required to take the following oath:

"In the name of the people and of the fatherland, I swear fidelity and devotion to the Parti Populaire Français, its ideals, and its leader. I swear to serve until the supreme sacrifice the cause of national and popular revolution which will leave a new, free and independent France."

The PPF is generally regarded to be a fascist party in its ideological, as well as its practical, orientation. The party denounced parliamentarianism and sought to limit French democracy and remake French society according to its own, authoritarian beliefs. It was vehemently opposed to both Marxism and liberalism and also wished to rid France of Freemasonry, about which it was greatly concerned.

It criticised supremacy of rationalism in politics and desired a move towards politics dictated by emotion and will rather than reason. Intellectuals who are often viewed as fascists, notably Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Ramón Fernandez, Alexis Carrel, Paul Chack, and Bertrand de Jouvenel, were members of the PPF at various times. Moreover, the PPF was anti-semitic.

It had initially been ambiguous towards anti-Semitism, expressing a negative view of Jews in their literature (associating Jews with banking interests) but allowing a Jew, Alexandre Abremski, to sit on its Politburo until his death in 1938. In 1936, Doriot stated: "Our party [the PPF] is not anti-Semitic. It is a great national party that has better things to do than fight Jews."[3] By 1938, PPF literature was filled with references to the "Judeo-masonic-bolshevik" conspiracy. As the PPF tended more towards fascism, and especially after the French defeat and the establishment of Vichy France, anti-Semitism became much more a central feature of party policy.

In 1941, Doriot, writing in the journal Au Pilori, would write: "... (t)he Jew is not a man. He's a stinking beast." This overt anti-semitic ideology was manifested by the paramilitary Gardes Françaises (formerly the Service d'Ordre), in which many PPF members operated[4] and which participated in wide-scale violence against Jews in France and North Africa and in the mass-deportation of Jews to concentration camps.

Apart from its anti-communism, the party also claimed to be anti-capitalist. Despite this, the PPF was financially supported by employers and French businessmen which sought to encourage a popular nationalist anti-Communist force and experienced rapid growth in its membership, particularly from the middle classes. The program of the party also did not envisage any nationalization of business and did not intend to undermine large property and free profit.[5][2]

The PPF during the war

After the French defeat in the Battle of France and the establishment of the regime of Philippe Pétain at Vichy, the PPF received additional support from Germany and increased its activities. The U.S. State Department placed it on a list of organizations under the direct control of the Nazi regime.[6] As a fascist party, the PPF was critical of the neotraditional authoritarian state established by Petain, criticizing the regime for being too moderate, and advocating closer military collaboration with Germany (such as sending troops to the Russian front), and modeling French government, and its racial policies, directly on those of Nazi Germany.

The PPF and the home front

The PPF increasingly placed anti-Semitism at its core as it collaborated with units of the Gestapo and the Milice, the French paramilitary organization led by Joseph Darnand, in violently rounding up Jews for deportation to concentration camps. The PPF paramilitaries participated in beatings, torture, assassinations and summary execution of Jews and political enemies of the Nazis. For this, the Germans rewarded them by allowing them the right to steal property from the Jews they arrested.

After Pierre Laval ascended to the leadership of the government on 18 April 1942, he requested that Nazi Germany allow him to force the PPF to merge into his own supporters, but the Nazis denied that request. However, as Laval moved France closer to the Nazi regime, the PPF ceased to be as useful to the Nazis as advocates of greater collaboration. As a result, the PPF was politically marginalized and their role as critics of the regime was diminished, although it did not cease entirely. By the end of the war, the PPF had virtually ceased to function as a political party, the attention of its leader and many of its members turning more directly to participation in the Nazi war effort.

The PPF and the collaborationist Rassemblement national populaire (RNP) also established the Comité ouvrier de secours immédiat in March 1942. This organisation sought to aid victims of the Allied bombing of France and, following the Normandy landings, aided refugees fleeing the fighting.[7]

Other groups linked to the PPF by common membership had less humanitarian motives: in Lyon a Mouvement national anti-terroriste was established to combat the Resistance by fighting "terror with terror"; other PPF members joined the Gardes Françaises set up by German police authorities as a counterweight to the Milice, which was deemed too French, or the Groupes d'action pour la justice sociale which hunted down French youth who went into hiding rather than do the mandatory labour work under the STO programme. These groups often operated beyond the control of the party.[8]

Debate exists as to whether PPF members actually fought against the Allies in Normandy. Doriot's biographers differ on the subject: Jean-Paul Brunet argues that the PPF did fight against the Allied invasion while Dieter Wolf denies any such action occurred.[9] However, Doriot, in German uniform, and Beugras, the clandestine PPF intelligence chief, visited the Normandy front in July 1944. PPF recruits were trained in espionage and sabotage and some were shot after being captured by the Allies while attempting to infiltrate Allied lines in Northern France.[10]

The PPF and wartime activities outside metropolitan France

In 1941, Doriot urged PPF members to join the newly formed Légion des Volontaires Français (LVF) to fight on the eastern front. The unit's performance was poor and the following year it was removed to anti-partisan actions in Belarus. In 1944 the LVF, along with a separate unit, the Waffen-SS Französische SS-Freiwilligen-Grenadier-Regiment (Waffen-SS French SS-Volunteer Grenadier Regiment), and French collaborators fleeing the Allied advance in the west were amalgamated into the Waffen-Grenadier-Brigade der SS "Charlemagne". In February 1945 the unit was officially upgraded to a division and renamed 33.Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS "Charlemagne". Doriot himself saw action and served three tours of duty on the Eastern Front between 1941 and 1944. In his absence, leadership of the PPF officially passed to a directorate. However effective leadership rested with Maurice-Yvan Sicard who resisted attempts to merge the party into a wider movement.[11]

The PPF attempted to aid German intelligence efforts and/or conduct sabotage activities in French territories occupied by the Allies. On 8 January 1943 a group of PPF militants originally from Maghreb, Germans and sympathetic Tunisians were parachuted into Southern Tunisia to conduct sabotage - but were arrested almost immediately.[12] From 1943 to 1944, PPF and collaborationist agents were parachuted into North Africa, where, under codename Atlas, they were to transmit information on Allied military preparations and the local political situation to PPF agents in France, who in turn, were to pass this information to German intelligence. These intelligence activities occurred under the aegis of Albert Beugras, head of the PPF's clandestine Service de renseignment, and whose activities were unknown even to the political cadres of the Party. Not only did Atlas fail to transmit the desired political information, but the head of the network, Edmond Latham, a professional soldier and former member of Vichy's Légion Tricolore, went over to the Free French and ensured that Atlas broadcast misinformation to the PPF and German intelligence. Atlas broadcast that the Allies intended to invade Sardinia or Greece rather than Sicily in 1943, therefore reinforcing British intelligence's famous Operation Mincemeat, and spread misinformation that disguised the Allied invasion plans of Italy and Provence. Atlas continued transmitting misinformation from Allied occupied Marseilles and Paris in 1944. Doriot and Beugras did not discover the 'treason' until 1945.[13]

In 1944, Doriot moved to Germany where he competed for the leadership of the French government-in-exile with the members of the former Vichy regime based in the Sigmaringen enclave. The PPF based itself in Mainau, set up its own radio station, Radio-Patrie, at Bad Mergentheim and published its own paper Le Petit Parisien.[14] The PPF was also involved in setting up training centres for French recruits to train operatives in conducting intelligence and sabotage activities, some of whom the Germans dropped by parachute into Allied occupied France.[15]

On 22 February 1945, Doriot, attired in his SS uniform and being driven in a Nazi officer's car, was killed by Allied strafers near Mengen, Württemberg, Germany, while en route from Mainau to Sigmaringen. The PPF movement did not survive the death of its leader, and no attempt was made to revive it in postwar France.

See also

- National Popular Rally — associated with former French Section of the Workers' International members

- Category:French Popular Party politicians

References

- ↑ "La résistible ascension du FN". raslfront.org. Archived from the original on 19 November 2003.

- 1 2 Winock, Michel (1994). Histoire de l'extrême droite en France (in French). Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-023200-5.

- ↑ "H-France Reviews". uakron.edu. Archived from the original on 11 March 2001.

- ↑ Cullen, Stephen M. (22 February 2018). World War II Vichy French Security Troops. ISBN 9781472827739.

- ↑ Payne, Stanley G. (1995). A History of Fascism, 1914–1945. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 297–298. ISBN 978-0-299-14874-4.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Olivier Pigoreau, "Rendez-vous tragique à Mengen" 53-61 in (2009) 34 Batailles: l'Histoire Militaire du XXe siècle 52-61, at 61, n.19 and p. 52

- ↑ Olivier Pigoreau, "Rendez-vous tragique à Mengen" 53-61 in (2009) 34 Batailles: l'Histoire Militaire du XXe siècle 52-61, p. 52

- ↑ Jean-Paul Brunet, Jacques Doriot, du communisme au fascisme Balland, 1996; Dieter Wolf, Doriot, du communisme à la collaboration Fayard, 1969

- ↑ See Olivier Pigoreau, "Rendez-vous tragique à Mengen" 53-61 in (2009) 34 Batailles: l'Histoire Militaire du XXe siècle 52-61, p. 52 and ensuing articles in the same series published in Batailles in 2009 about the PPF

- ↑ David Littlejohn, The Patriotic Traitors, London: Heinemann, 1972, p. 272

- ↑ Olivier Pigoreau, "Le PPF en guerre - Node de Code: Atlas" 36 (2009) Batailles: L'histoire militaire du XXe siècle, 60-69, at p.62

- ↑ see Paul Paillole (wartime commander of the Sécurité militaire, who helped turn Atlas), Services spéciaux, 1935-1945 éditions Robert Laffont, 1975, 484-488, 496) and Olivier Pigoreau, "Le PPF en guerre - Node de Code: Atlas" 36 (2009) Batailles: L'histoire militaire du XXe siècle, 60-69. Paillole notes that post-war communication with his Abewehr counterpart, Lt. Col. Oscar Reile, suggests that the Abewehr was aware that Atlas had been turned within months (p. 488). Pigoreau suggests that the Abewehr may have allowed the dangerous misinformation to influence Germany's OKW nonetheless as part of the resistance to the Nazi regime within the Abewehr (p. 69).

- ↑ Olivier Pigoreau, "Rendez-vous tragique à Mengen" 53-61 in (2009) 34 Batailles: l'Histoire Militaire du XXe siècle 52-61

- ↑ see Pierre-Philippe Lambert and Gérard Le Marrec, Les Français sous le casque allemand Granchier, 1994. Some 95 Frenchmen were dropped into Allied occupied France, but some were Milice or Franciste members.

- Robert Soucy, French Fascism: The Second Wave 1933-1939, 1995

- G. Warner, 'France', in SJ Woolf, Fascism In Europe, 1981

- Christopher Lloyd, Collaboration and Resistance in Occupied France: Representing Treason and Sacrifice, Palgrave MacMillan 2003

.svg.png.webp)