Republic of Botswana | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Pula "Let There Be Rain" | |

| Anthem: Fatshe leno la rona "Blessed Be This Noble Land" | |

.svg.png.webp)  | |

| Capital and largest city | Gaborone 24°39.5′S 25°54.5′E / 24.6583°S 25.9083°E |

| Official languages | English[1] |

| National language | Setswana[1] |

| Ethnic groups (2012[2]) |

|

| Religion (2021) |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary dominant-party parliamentary republic with an executive presidency[4][5] |

| Mokgweetsi Masisi[6] | |

| Slumber Tsogwane | |

| Phandu Skelemani | |

| Legislature | Parliament (National Assembly) |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

• Established (Constitution) | 30 September 1966 |

| Area | |

• Total | 581,730 km2 (224,610 sq mi)[7] (47th) |

• Water (%) | 2.7 |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 2,675,352[8] (145th) |

• 2023 census | 2,675,352 [9] |

• Density | 4.6/km2 (11.9/sq mi) (231st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2015) | high |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 117th |

| Currency | Pula (BWP) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (Central Africa Time[13]) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +267 |

| ISO 3166 code | BW |

| Internet TLD | .bw |

Website www | |

| Tswana | |

|---|---|

| Person | Motswana |

| People | Batswana |

| Language | Setswana |

| Country | Botswana |

Botswana (English: Land of the Tswana; /bɒtˈswɑːnə/ ⓘ, also UK: /bʊt-, bʊˈtʃw-/[14]), officially the Republic of Botswana (Setswana: Lefatshe la Botswana, [lɪˈfatsʰɪ la bʊˈtswana]), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. Botswana is topographically flat, with approximately 70 percent of its territory being the Kalahari Desert. It is bordered by South Africa to the south and southeast, Namibia to the west and north, and Zimbabwe to the northeast. It is connected by the Kazungula Bridge[15] to Zambia, across the world's shortest border between two countries.

A country of slightly over 2.3 million people,[16] Botswana is one of the most sparsely populated countries in the world. It is essentially the nation state of the Tswana, who make up 79% of the population.[17] About 11.6 per cent of the population lives in the capital and largest city, Gaborone. Formerly one of the world's poorest countries—with a GDP per capita of about US$70 per year in the late 1960s—it has since transformed itself into an upper-middle-income country, with one of the world's fastest-growing economies.[18]

Modern-day humans first inhabited the country over 200,000 years ago. The Tswana ethnic group were descended mainly from Bantu-speaking tribes who migrated southward of Africa to modern Botswana around 600 CE, living in tribal enclaves as farmers and herders. In 1885, the British colonised the area and declared a protectorate under the name of Bechuanaland. As decolonisation occurred, Bechuanaland became an independent Commonwealth republic under its current name on 30 September 1966.[19] Since then, it has been a representative republic, with a consistent record of uninterrupted democratic elections and the lowest perceived corruption ranking in Africa since at least 1998.[20]

The economy is dominated by mining and tourism. Botswana has a GDP (purchasing power parity) per capita of about $18,113 as of 2021, one of the highest in subsaharan Africa.[2] Botswana is the world's biggest diamond producing country. Its relatively high gross national income per capita (by some estimates the fourth-largest in Africa) gives the country a relatively high standard of living and the third-highest Human Development Index of continental Sub-Saharan Africa (after Gabon and South Africa).[21][12] Botswana is the first African country to host Forbes 30 Under 30[22] and the 2017 Netball World Youth Cup.

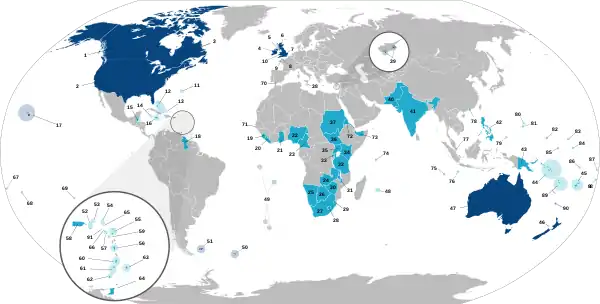

Botswana is a member of the Southern African Customs Union, the Southern African Development Community, the Commonwealth of Nations, and the United Nations. The country has been adversely affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In 2002, Botswana became the first country to offer anti-retroviral drugs (ARVs) to help combat the epidemic.[23] Despite the launch of programs to make treatment available and to educate the populace about the epidemic,[24] the number of people with AIDS rose from 290,000 in 2005 to 320,000 in 2013.[25]: A20 As of 2014, Botswana had the third-highest prevalence rate for HIV/AIDS, with roughly 20% of the population infected.[26] However, in recent years the country has made strides in combatting HIV/AIDS, with efforts being made to provide proper treatment and lower the rate of mother-to-child transmission.[27][28]

Etymology

The country's name means "Land of the Tswana", referring to the dominant ethnic group in Botswana.[29] The Constitution of Botswana recognizes a homogeneous Tswana state.[30] The term Batswana was originally applied to the Tswana, which is still the case.[31] However, it has also come to be used generally as a demonym for all citizens of Botswana.[32]

History

Early history

Archaeological digs demonstrate that hominids lived in Botswana for around two million years. Stone tools and fauna remains have shown that all areas of the country were inhabited at least 400,000 years ago.[33]

In October 2019, researchers reported that Botswana was the birthplace of all modern humans about 200,000 years ago.[34][35] Evidence left by modern humans, such as cave paintings, is about 73,000 years old.[36] The earliest known inhabitants of southern Africa are thought to have been the forebears of present-day San ("Bushmen") and Khoi peoples. Both groups speak click languages from the small Khoe-Kwadi, Kx’a and Tuu families whose members hunted, gathered, and traded over long distances. When cattle were first introduced about 2000 years ago into southern Africa, pastoralism became a major feature of the economy, since the region had large grasslands free of tsetse flies.[37]

It is unclear when Bantu-speaking peoples first moved into the country from the north, although 600 CE seems to be a consensus estimate. In that era the ancestors of the modern-day Kalanga moved into what is now the north-eastern areas of the country. These proto-Kalanga were closely connected to states in Zimbabwe as well as to the Mapungubwe state and the notable of these was Domboshaba ruins, a cultural and heritage site in Botswana originally occupied towards the end of the Great Zimbabwe period (1250–1450), with stone walls that have an average height of 1.8 metres. The site is a respected place for the people living in the region and it is believed that the chief lived on the top of the hill together with his helpers or assistants. These states, located outside of current Botswana's borders, appear to have kept massive herds of cattle in what is now the Central District—apparently at numbers approaching modern cattle density.[38] This massive cattle-raising complex prospered until 1300 CE or so and seems to have regressed following the collapse of Mapungubwe. During this era the first Tswana-speaking groups, the Bakgalagadi, moved into the southern areas of the Kalahari. All these various peoples were connected to trade routes that ran via the Limpopo River to the Indian Ocean, and trade goods from Asia such as beads made their way to Botswana, most likely in exchange for ivory, gold and rhinoceros horn.[39]

Toutswemogala Hill Iron Age Settlement's radio-carbon dates for this settlement range from 7th to late 19th century indicating occupation of more than one thousand years. The hill was part of the formation of early states in Southern Africa with cattle keeping as major source of economy. Toutswe settlement include house-floors, large heaps of vitrified cow-dung and burials while the outstanding structure is the stone wall. There are large tracts of centaurs ciliaris, a type of grass which has come to be associated with cattle-keeping settlements in South, Central Africa. Around 700 CE, the Toutswe people moved westward into Botswana and began an agricultural and pastoral land tenure system based on sorghum and millet, and domesticated stock, respectively.[40] The site was situated in the centre of a broader cultural area in Eastern Botswana and shares many commonalities with other archaeological sites of this region, in both ceramic production styles and also time frames inhabited. Large structures were observed that contained vitrified remains of animal dung, leading to the theory that these were animal enclosures and that Toutswemogala Hill was thus a major centre of animal husbandry in the region.[40]

However, agriculture also played a vital role in the longevity of Toutswemogala Hill's extended occupation, as many grain storage structures have also been found on the site. Many different stratified layers of housing floors further signal continuous occupation over hundreds of years. The arrival of the ancestors of the Tswana-speakers who came to control the region has yet to be dated precisely. Members of the Bakwena, a chieftaincy under a legendary leader named Kgabo II, made their way into the southern Kalahari by 1500 CE, at the latest, and his people drove the Bakgalagadi inhabitants west into the desert. Over the years, several offshoots of the Bakwena moved into adjoining territories. The Bangwaketse occupied areas to the west, while the Bangwato moved northeast into formerly Kalanga areas.[41] Not long afterwards, a Bangwato offshoot known as the Batawana migrated into the Okavango Delta, probably in the 1790s.[42]

Effects of the Mfecane and Batswana-Boer Wars

The first written records relating to modern-day Botswana appear in 1824. What these records show is that the Bangwaketse had become the predominant power in the region. Under the rule of Makaba II, the Bangwaketse kept vast herds of cattle in well-protected desert areas, and used their military prowess to raid their neighbours.[43] Other chiefdoms in the area, by this time, had capitals of 10,000 or so and were fairly prosperous.[44] This equilibrium came to end during the Mfecane period, 1823–1843, when a succession of invading peoples from South Africa entered the country. Although the Bangwaketse were able to defeat the invading Bakololo in 1826, over time all the major chiefdoms in Botswana were attacked, weakened, and impoverished. The Bakololo and AmaNdebele raided repeatedly and took large numbers of cattle, women, and children from the Batswana—most of whom were driven into the desert or sanctuary areas such as hilltops and caves. Only after 1843, when the Amandebele moved into western Zimbabwe, did this threat subside.[45]

During the 1840s and 1850s trade with Cape Colony-based merchants opened up and enabled the Batswana chiefdoms to rebuild. The Bakwena, Bangwaketse, Bangwato and Batawana cooperated to control the lucrative ivory trade and then used the proceeds to import horses and guns, which in turn enabled them to establish control over what is now Botswana. This process was largely complete by 1880, and thus the Bushmen, the Kalanga, the Bakgalagadi, and other current minorities were subjugated by the Batswana.[46] The earliest known map of Botswana dates from 1849, drawn by David Livingstone.[47]

Following the Great Trek, Afrikaners from the Cape Colony established themselves on the borders of Botswana in the Transvaal. In 1852 a coalition of Tswana chiefdoms led by Sechele I defeated Afrikaner incursions at the Battle of Dimawe and, after about eight years of intermittent tensions and hostilities, eventually came to a peace agreement in Potchefstroom in 1860. From that point on, the modern-day border between South Africa and Botswana was agreed on, and the Afrikaners and Batswana traded and worked together comparatively peacefully.[48][49]

In 1884 Batawana, a northern based Tswana clan's cavalry under the command of Kgosi Moremi fought and defeated the Ndebele's invasion of northern Botswana at the Battle of Khutiyabasadi. This blow to the larger invading Ndebele force signalled the start of the collapse of the Ndebele Kingdom in Zimbabwe and helped galvanise Tswana speaking authority of the area now making part of northern Botswana.[50]

Due to newly peaceful conditions, trade thrived between 1860 and 1880. Taking advantage of this were Christian missionaries. The Lutherans and the London Missionary Society both became established in the country by 1856. By 1880, every major village had a resident missionary, and their influence slowly became felt. Khama III (reigned 1875–1923) was the first of the Tswana chiefs to make Christianity a state religion and changed a great deal of Tswana customary law as a result. Christianity became the de facto official religion in all the chiefdoms by World War I.[51]

Colonialism and the Bechuanaland Protectorate

During the Scramble for Africa the territory of Botswana was coveted by both the German Empire and Britain. During the Berlin Conference, Britain decided to annex Botswana in order to safeguard the Road to the North and thus connect the Cape Colony to its territories further north. It unilaterally annexed Tswana territories in January 1885 and then sent the Warren Expedition north to consolidate control over the area and convince the chiefs to accept British overrule. Despite their misgivings, they eventually acquiesced to this fait accompli.[52][53]

In 1890 areas north of 22 degrees were added to the new Bechuanaland Protectorate. During the 1890s the new territory was divided into eight different reserves, with fairly small amounts of land being left as freehold for white settlers. During the early 1890s, the British government decided to hand over the Bechuanaland Protectorate to the British South Africa Company. This plan, which was well on its way to fruition despite the entreaties of Tswana leaders who toured England in protest, was eventually foiled by the failure of the Jameson Raid in January 1896.[54][55]

When the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910 from the main British colonies in the region, the High Commission Territories—the Bechuanaland Protectorate, Basutoland (now Lesotho), and Swaziland (now Eswatini)—were not included, but provision was made for their later incorporation. However, the UK began to consult with their inhabitants as to their wishes. Although successive South African governments sought to have the territories transferred to their jurisdiction, the UK kept delaying; consequently, it never occurred. The election of the Nationalist government in 1948, which instituted apartheid, and South Africa's withdrawal from the Commonwealth in 1961, ended any prospect of the UK or these territories agreeing to incorporation into South Africa.[56]

An expansion of British central authority and the evolution of native government resulted in the 1920 establishment of two advisory councils to represent both Africans and Europeans.[57] The African Council consisted of the eight heads of the Tswana tribes and some elected members.[57] Proclamations in 1934 regulated tribal rule and powers. A European-African advisory council was formed in 1951, and the 1961 constitution established a consultative legislative council.

Independence

In June 1964, the United Kingdom accepted proposals for a democratic self-government in Botswana. An independence conference was held in London in February 1966.[58] The seat of government was moved in 1965 from Mahikeng in South Africa, to the newly established Gaborone, which is located near Botswana's border with South Africa. Based on the 1965 constitution, the country held its first general elections under universal suffrage and gained independence on 30 September 1966.[59] Seretse Khama, a leader in the independence movement and the legitimate claimant to the Ngwato chiefship, was elected as the first president, and subsequently re-elected twice.

Queen Elizabeth II, accompanied by Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh and her son Prince Andrew, Duke of York, arrived in Botswana during the fourth-leg tour of Africa on 25–27 July 1979. During their visit, they were greeted by tribal dancers and a 21-gun salute.

Khama died in office in 1980. The presidency passed to the sitting vice-president, Quett Masire, who was elected in his own right in 1984 and re-elected in 1989 and 1994. Masire retired from office in 1998. He was succeeded by Festus Mogae, who was elected in his own right in 1999 and re-elected in 2004. The presidency passed in 2008 to Ian Khama (son of the first president), who had been serving as Mogae's vice-president since resigning his position in 1998 as Commander of the Botswana Defence Force to take up this civilian role. On 1 April 2018 Mokgweetsi Eric Keabetswe Masisi was sworn in as the fifth president of Botswana, succeeding Ian Khama. He represents the Botswana Democratic Party, which has also won a majority in every parliamentary election since independence. All the previous presidents have also represented the same party.[60]

A long-running dispute over the northern border with Namibia's Caprivi Strip was the subject of a ruling by the International Court of Justice in December 1999. It ruled that Kasikili Island belongs to Botswana.[61]

In 2014, the Okavango Delta of Botswana, the largest inland delta in the world, was inscribed as the 1,000th World Heritage Site.

In the 1970s, Botswana held a reputation of being one the world's principal producers of diamonds.[62] This reputation has held into the modern day as Botswana's diamond mining industry is among the world's largest.[63][64] Botswana's Jwaneng mine in particular is the world's richest.[65]

Geography

At 581,730 km2 (224,607 sq mi) Botswana is the world's 48th-largest country. It is similar in size to Madagascar or France. It lies between latitudes 17° and 27° south, and longitudes 20° and 30° east.

Botswana is predominantly flat, tending towards gently rolling tableland. Botswana is dominated by the Kalahari Desert, which covers up to 70% of its land surface. The Okavango Delta, one of the world's largest inland river deltas, is in the north-west. The Makgadikgadi Pan, a large salt pan, lies in the north.

The Limpopo River Basin, the major landform of all of southern Africa, lies partly in Botswana, with the basins of its tributaries, the Notwane, Bonwapitse, Mahalapye, Lotsane, Motloutse and the Shashe, located in the eastern part of the country. The Notwane provides water to the capital through the Gaborone Dam. The Chobe River lies to the north, providing a boundary between Botswana and Namibia's Zambezi Region. The Chobe River meets with the Zambezi River at a place called Kazungula (meaning a small sausage tree, a point where Sebitwane and his Makololo tribe crossed the Zambezi into Zambia).

Biodiversity and conservation

%252C_vista_a%C3%A9rea_del_delta_del_Okavango%252C_Botsuana%252C_2018-08-01%252C_DD_28.jpg.webp)

Botswana has diverse areas of wildlife habitat. In addition to the delta and desert areas, there are grasslands and savannas, where blue wildebeest, antelopes, and other mammals and birds are found. Northern Botswana has one of the few remaining large populations of the endangered African wild dog. Chobe National Park, found in the Chobe District, has the world's largest concentration of African elephants. The park covers about 11,000 km2 (4,247 sq mi) and supports about 350 species of birds.

The Chobe National Park and Moremi Game Reserve (in the Okavango Delta) are major tourist destinations. Other reserves include the Central Kalahari Game Reserve located in the Kalahari Desert in Ghanzi District; Makgadikgadi Pans National Park and Nxai Pan National Park are in Central District in the Makgadikgadi Pan. Mashatu Game Reserve is privately owned, located at the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo Rivers in eastern Botswana. The other privately owned reserve is Mokolodi Nature Reserve near Gaborone. There are also specialised sanctuaries like Khama Rhino Sanctuary (for rhinoceros) and Makgadikgadi Sanctuary (for flamingos). They are both located in Central District.

.jpg.webp)

Giraffe crossing a road (bottom).

Botswana faces two major environmental problems, drought and desertification, which are heavily linked. Three-quarters of the country's human and animal populations depend on groundwater due to drought. Groundwater use through deep borehole drilling has somewhat eased the effects of drought. Surface water is scarce in Botswana and less than 5% of the agriculture in the country is sustainable by rainfall. In the remaining 95% of the country, raising livestock is the primary source of rural income. Approximately 71% of the country's land is used for communal grazing, which has been a major cause of the desertification and the accelerating soil erosion of the country.[66]

Since raising livestock has been profitable for the people of Botswana, they continue to exploit the land with dramatically increasing numbers of animals. From 1966 to 1991, the livestock population grew from 1.7 million to 5.5 million.[66]: 64 Similarly, the human population has increased from 574,000 in 1971 to 1.5 million in 1995, a 161% increase in 24 years. Over 50% of all households in Botswana own cattle, which is currently the largest single source of rural income. Rangeland degradation or desertification is regarded as the reduction in land productivity as a result of overstocking and overgrazing, or as a result of veld product gathering for commercial use. Degradation is exacerbated by the effects of drought and climate change.[66]

Environmentalists report that the Okavango Delta is drying up due to the increased grazing of livestock.[67] The Okavango Delta is one of the major semi-forested wetlands in Botswana and one of the largest inland deltas in the world; it is a crucial ecosystem to the survival of many animals.[67]

The Department of Forestry and Range Resources has already begun to implement a project to reintroduce indigenous vegetation into communities in Kgalagadi South, Kweneng North and Boteti.[68] Reintroduction of indigenous vegetation will help reduce the degradation of the land. The United States Government has also entered into an agreement with Botswana, giving them US$7 million to reduce Botswana's debt by US$8.3 million. The stipulation of the US reducing Botswana's debt is that Botswana will focus on more extensive conservation of the land.[67] The country had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 9.13/10, ranking it 8th globally out of 172 countries.[69]

The United Nations Development Programme claims that poverty is a major problem behind the overexploitation of resources, including land, in Botswana. To help change this the UNDP joined in with a project started in the southern community of Struizendam in Botswana. The purpose of the project is to draw from "indigenous knowledge and traditional land management systems". The leaders of this movement are supposed to be the people in the community, to draw them in, in turn increasing their possibilities to earn an income and thus decreasing poverty. The UNDP also stated that the government has to effectively implement policies to allow people to manage their own local resources and are giving the government information to help with policy development.[70]

Government and politics

Botswana is a parliamentary republic governed by the Constitution of Botswana,[71] and it is the longest uninterrupted democracy in Africa.[72] Its seat of government is in Gaborone.[73] Botswana's governing institutions were established after it became an independent nation in 1966. Botswana's governmental structure is based on both the Westminster system of the United Kingdom and the tribal governments of the Tswana people.[71] Botswana has a centralised government in which national law supersedes local law.[74] Local laws are developed by local councils and district councils.[75] They are heavily influenced by tribal governments, which are led by the tribe's chief.[75]

The Parliament of Botswana consists of the National Assembly, which serves as the nation's formal legislature, and the Ntlo ya Dikgosi, an advisory body made up of tribal chiefs and other appointed members.[76] Botswana's executive branch is led by the President of Botswana, who serves as both the head of state and head of government.[71] The members of parliament choose the president,[77] and the president then appoints the Vice-President and the members of the Cabinet.[78] The president has significant power in Botswana, and the legislature has little power to check the president once appointed.[77][79] The judiciary includes the High Court of Botswana, the Court of Appeal, and Magistrates' Courts.[80] Cases are often settled by customary courts with tribal chiefs presiding.[75]

Elections in Botswana are held every five years and overseen by the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC).[81] Botswana operates a multi-party system in which many political parties compete in elections,[72] but it is effectually a dominant-party state in which the Botswana Democratic Party has ruled with a majority government since independence.[82][83] The nation's elections are recognised as free and fair, but the ruling party has institutional advantages that other parties do not.[81][84] Factionalism is common within Botswana's political parties, and several groups have formed new parties by splitting from established ones.[72] Since 2019, the Umbrella for Democratic Change has operated as a coalition of opposition parties.[85] The most recent election was held in 2019, with the Botswana Democratic Party maintaining its majority and Mokgweetsi Masisi being re-elected president.[86]

In Botswana's early years, its politics were managed by President Seretse Khama and Vice-President (later president) Quett Masire.[87] Since the Kgabo Commission in 1991, factionalism and political rivalries have dominated Botswana politics. The Barata-Phathi faction was led by Peter Mmusi, Daniel Kwelagobe, and Ponatshego Kedikilwe, while the A-Team faction was led by Mompati Merafhe and Jacob Nkate.[88][89] When Festus Mogae and Ian Khama became president and vice-president, respectively, they aligned with the A-Team. Khama effectively expelled the A-Team from the party in 2010 after he became president.[89] A new rivalry formed in 2018 when Khama's chosen successor, Mokgweetsi Masisi, became president. He opposed Khama, and the two formed a political rivalry that looms over Batswana politics in the 2020s.[90]

Foreign relations and military

At the time of independence, Botswana had no armed forces. It was only after the Rhodesian and South African armies attacked the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army and Umkhonto we Sizwe[91] bases respectively that the Botswana Defence Force (BDF) was formed in 1977.[92] The president is commander-in-chief of the armed forces and appoints a defence council and the BDF currently consists of roughly 60,000 servicemen. In 2019, Botswana signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[93]

Following political changes in South Africa and the region, the BDF's missions have increasingly focused on prevention of poaching, preparing for disasters, and foreign peacekeeping. The United States has been the largest single foreign contributor to the development of the BDF, and a large segment of its officer corps have received U.S. training. The Botswana government gave the United States permission to explore the possibility of establishing an Africa Command (AFRICOM) base in the country.[94]

Human rights

Many of the indigenous San people have been forcibly relocated from their land to reservations. To make them relocate, they were denied access to water on their land and faced arrest if they hunted, which was their primary source of food.[95] Their lands lie in the middle of the world's richest diamond field. Officially, the government denies that there is any link to mining and claims the relocation is to preserve the wildlife and ecosystem, even though the San people have lived sustainably on the land for millennia.[95] On the reservations they struggle to find employment, and alcoholism is rampant.[95] On 24 August 2018 the UN Special Rapporteur on Minorities, Fernand de Varennes, issued a statement calling on Botswana "to step up efforts to recognise and protect the rights of minorities in relation to public services, land and resource use and the use of minority languages in education and other critical areas."

Botswana was ranked as a "flawed democracy" and 30th out of 167 states in the 2021 Democracy Index (The Economist), higher than Italy and Belgium, and just below the Czech Republic. This was the second highest rating in Africa, and highest ranking in continental Africa (only the offshore island nation of Mauritius bested its ranking). According to 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices Botswana ranks as 75th electoral democracy worldwide and 12th electoral democracy in Africa. According to Transparency International, Botswana is the least corrupt country in Africa and ranks just below Portugal and South Korea.[96]

Until June 2019, homosexual acts were illegal in Botswana. A Botswana High Court decision of 11 June of that year struck down provisions in the Criminal Code that punished "carnal knowledge of any person against the order of nature" and "acts of gross indecency", making Botswana one of twenty-two African countries that have either decriminalised or legalised homosexual acts.[97]

Capital punishment is a legal penalty for murder in Botswana, and executions are carried out by hanging.[98]

The Botswana Centre for Human Rights, Ditshwanelo, was established in 1993.[99]

Administrative divisions

.svg.png.webp)

Botswana's ten districts are:

- Southern District

- South-East District

- Kweneng District

- Kgatleng District

- Central District

- North-East District

- Ngamiland District

- Kgalagadi District

- Chobe District

- Ghanzi District

Botswana's councils created from urban or town councils are: Gaborone City, Francistown, Lobatse Town, Selebi-Phikwe Town, Jwaneng Town, Orapa Town and Sowa Township.

Economy

Since independence, Botswana has had one of the fastest growth rates in per capita income in the world.[100] Botswana has transformed itself from one of the poorest countries in the world to an upper middle-income country. GDP per capita grew from $1,344 in 1950 to $15,015 in 2016.[101] Although Botswana was resource-abundant, a good institutional framework allowed the country to reinvest resource-income in order to generate stable future income.[102] By one estimate, it has the fourth highest gross national income at purchasing power parity in Africa, giving it a standard of living around that of Mexico.[103]

%252C_%25_of_world_average%252C_1960-2012%253B_Zimbabwe%252C_South_Africa%252C_Botswana%252C_Zambia%252C_Mozambique.png.webp)

The Ministry of Trade and Industry of Botswana is responsible for promoting business development throughout the country. According to the International Monetary Fund, economic growth averaged over 9% per year from 1966 to 1999. Botswana has a high level of economic freedom compared to other African countries.[104] The government has maintained a sound fiscal policy, despite consecutive budget deficits in 2002 and 2003, and a negligible level of foreign debt. It earned the highest sovereign credit rating in Africa and has stockpiled foreign exchange reserves (over $7 billion in 2005/2006) amounting to almost two and a half years of current imports.[105]

The constitution provides for an independent judiciary, and the government respects this in practice. The legal system is sufficient to conduct secure commercial dealings, although a serious and growing backlog of cases prevents timely trials. The protection of intellectual property rights has improved significantly. Botswana is ranked second only to South Africa among sub-Saharan Africa countries in the 2014 International Property Rights Index.[106]

While generally open to foreign participation in its economy, Botswana reserves some sectors for citizens. Increased foreign investment plays a significant role in the privatisation of state-owned enterprises. Investment regulations are transparent, and bureaucratic procedures are streamlined and open, although somewhat slow. Investment returns such as profits and dividends, debt service, capital gains, returns on intellectual property, royalties, franchise's fees, and service fees can be repatriated without limits.

Botswana imports refined petroleum products and electricity from South Africa. There is some domestic production of electricity from coal.

Energy

Energy in Botswana is a growing industry with tremendous potential. However almost all Botswana's electricity is generated from coal.[107] No petroleum reserves have been identified and all petroleum products are imported refined, mostly from South Africa. There is extensive woody biomass from 3 to 10t / hectare.

Recently, the country has taken a large interest in renewable energy sources and has completed a comprehensive strategy that may attract investors in the wind, solar and biomass renewable energy industries. Botswana's power stations include Morupule Power Stations B(600 MW), and A (132 MW),[108] Orapa Power Station (90 MW) and Phakalane Power Station (1.3 MW).

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) undertook an evaluation of the national energy sector in 2021 and found that Botswana could meet 15% of its energy needs in 2030 from its indigenous solar, wind, and bioenergy resources.[109][110]Transport

During SONA 2020 summit it was announced that Botswana has a network of roads, of varied quality and capacity, totalling about 31,747 kilometres (19,727 mi). Of these, 20,000 kilometres (12,000 mi) are paved (this is including 134 kilometres (83 mi) of motorways.[111] The remaining 11,747 kilometres (7,299 mi) worth are unpaved. Road distances are shown in kilometres and speed limits are indicated in kilometres per hour (kph) or by the use of the national speed limit (NSL) symbol. Some vehicle categories have various lower maximum limits enforced by speed limits, for example trucks.[112]

Finance

An array of financial institutions populates the country's financial system, with pension funds and commercial banks being the two most important segments by asset size. Banks remain profitable, well-capitalised, and liquid, as a result of growing national resources and high interest rates.[113] The Bank of Botswana serves as a central bank. The country's currency is the Botswana pula.

Botswana's competitive banking system is one of Africa's most advanced. Generally adhering to global standards in the transparency of financial policies and banking supervision, the financial sector provides ample access to credit for entrepreneurs. The Capital Bank opened in 2008.[114] As of August 2015, there are a dozen licensed banks in the country.[115] The government is involved in banking through state-owned financial institutions and a special financial incentives programme that is aimed at increasing Botswana's status as a financial centre. Credit is allocated on market terms, although the government provides subsidised loans. Reform of non-bank financial institutions has continued in recent years, notably through the establishment of a single financial regulatory agency that provides more effective supervision.[116] The government has abolished exchange controls, and with the resulting creation of new portfolio investment options, the Botswana Stock Exchange is growing.[117]

Gemstones and precious metals

In Botswana, the Department of Mines[118] and Mineral Resources, Green Technology and Energy Security[119] led by Hon Sadique Kebonang in Gaborone, maintains data regarding mining throughout the country. Debswana, the largest diamond mining company operating in Botswana, is 50% owned by the government.[120] The mineral industry provides about 40% of all government revenues.[121] In 2007, significant quantities of uranium were discovered, and mining was projected to begin by 2010. Several international mining corporations have established regional headquarters in Botswana, and prospected for diamonds, gold, uranium, copper, and even oil, many coming back with positive results. Government announced in early 2009 that they would try to shift their economic dependence on diamonds, over serious concern that diamonds are predicted to dry out in Botswana over the next twenty years.

Botswana's Orapa mine is the largest diamond mine in the world in terms of value and quantity of carats produced annually.[122] Estimated to have produced over 11 million carats in 2013, with an average price of $145/carat, the Orapa mine was estimated to produce over $1.6 billion worth of diamonds in 2013.[123]

Creative industries

Increasing importance is being given to the economic contribution of the creative industries to national economies. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) recompiles statistics about the export and import of goods and services related to the creative industries.[124] The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) has assisted in the preparation of national studies measuring the size of over 50 copyright industries around the world.[125] According to the WIPO compiled data, the national contribution of creative industries varies from 2% to 11% depending on the country.

Using the WIPO-framework, the Companies and Intellectual Property Authority(CIPA) and the Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis were published by a sector-specific study in 2019.[126] In 2016, copyright industries contributed 5.46% to value-added and 2.66% to the total labour force, 1.28% to exports, and 3.47% to imports.

Demographics

| Year | Million |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 0.4 |

| 2000 | 1.7 |

| 2020 | 2.4 |

As of 2012, the Tswana are the majority ethnic group in Botswana, making up approximately 79% of the population, followed by Kalanga at 11% and the San (Basarwa) at 3%. The remaining 7% is made up of White Batswana/European Batswana,[129] Indians,[2] and a number of other smaller Southern African ethnic groups.

Native groups include the Bayei, Bambukushu, Basubia, Baherero and Bakgalagadi. The Indian minority is made up of both recent migrants and descendants of Indian migrants who arrived from Mozambique, Kenya, Tanzania, Mauritius and South Africa.

Since 2000, because of deteriorating economic conditions in Zimbabwe, the number of Zimbabweans in Botswana has risen into the tens of thousands.[130] Fewer than 10,000 San people are still living their traditional hunter-gatherer way of life. Since the mid-1990s the central government of Botswana has been trying to move San out of their historic lands.[131]

James Anaya, as the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people for the United Nations in 2010, described loss of land as a major contributor to many of the problems facing Botswana's indigenous people, citing the San's eviction from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR)[132] as a special example.[133]: 2 Among Anaya's recommendations in a report to the United Nations Human Rights Council was that development programs should promote, in consultation with indigenous communities such as the San and Bakgalagadi people, activities in harmony with the culture of those communities such as traditional hunting and gathering activities.[133]: 19

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Gaborone .jpg.webp) Francistown |

1 | Gaborone | South-East | 246,325 | 11 | Kanye | Southern | 48,028 |  Maun |

| 2 | Francistown | North-East | 103,417 | 12 | Selibe Phikwe | Central | 42,488 | ||

| 3 | Mogoditshane | Kweneng | 88,006 | 13 | Letlhakane | Central | 36,338 | ||

| 4 | Maun | North-West | 84,993 | 14 | Ramotswa | South-East | 33,271 | ||

| 5 | Molepolole | Kweneng | 74,674 | 15 | Lobatse | South-East | 29,772 | ||

| 6 | Serowe | Central | 55,676 | 16 | Mmopane | Kweneng | 25,345 | ||

| 7 | Tlokweng | South-East | 55,508 | 17 | Thamaga | Kweneng | 25,297 | ||

| 8 | Palapye | Central | 52,636 | 18 | Moshupa | Southern | 23,858 | ||

| 9 | Mochudi | Kgatleng | 50,317 | 19 | Tonota | Central | 23,296 | ||

| 10 | Mahalapye | Central | 48,431 | 20 | Bobonong | Central | 21,216 | ||

Languages

The official language of Botswana is English, while Setswana is widely spoken across the country.[1] In Setswana, prefixes are more important than they are in many other languages, since Setswana is a Bantu language and has noun classes denoted by these prefixes. They include Bo, which refers to the country, Ba, which refers to the people, Mo, which is one person, and Se which is the language. For example, the main ethnic group of Botswana is the Tswana people, hence the name Botswana for its country. The people as a whole are Batswana, one person is a Motswana, and the language they speak is Setswana.

Other languages spoken in Botswana include Kalanga (Sekalanga), Sarwa (Sesarwa), Ndebele, Kgalagadi, Tswapong, !Xóõ, Yeyi, and, in some parts, Afrikaans.

Religion

An estimated 77% of the country's citizens identify as Christians. Anglicans, Methodists, and the United Congregational Church of Southern Africa make up the majority of Christians. There are also congregations of Lutherans, Baptists, Roman Catholics, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Dutch Reformed Church, Mennonites, Seventh-day Adventists, Jehovah's Witnesses and Serbian Orthodox in the country. According to the 2001 census, the nation has around 5,000 Muslims (mainly from South Asia), 3,000 Hindus, and 700 of the Baháʼí Faith. Approximately 20% of citizens identify with no religion.

Culture

Literature and cinema

Botswana literature belongs somewhere in the strong African literary writing circles. African literature is known for its consciousness and didactic writing styles. Writing as an art form has existed in Botswana for a long while, from the rock painting era — especially in the Tsodilo Hills, known to be 20,000 years old — to the present day, with the movie production of The No.1 Ladies Detective Agency, based on a series of more than 20 novels set in Botswana.

.jpg.webp)

In recent times and to date Botswana has seen a remarkable appearance of distinguished writers whose genres range from historical, political and witty story writing. Prominent amongst these are the South African-born Bessie Head, who settled in Serowe; Andrew Sesinyi; Barolong Seboni (whose works include Images of the Sun, Screams and Pleas, Lovesongs, Windsongs of the Kgalagadi and Lighting the Fire, and several other publications that include a play, Sechele I, and Setswana Riddles Translated into English); Unity Dow, Galesiti Baruti; Caitlin Davies; Lauri Kubuetsile; Albert Malikongwa; Toro Mositi; and Moteane Melamu.[136]

Most of Bessie Head's important works are set in Serowe. When Rain Clouds Gather (1968), Maru (1971), and A Question of Power (1973) all have this setting. The three are also autobiographical; When Rain Clouds Gather is based on her experience living on a development farm, Maru incorporates her experience of being considered racially inferior, and A Question of Power draws on her understanding of what it was like to experience acute psychological distress. Head also published a number of short stories, including the collection The Collector of Treasures (1977). She published a book on the history of Serowe, Serowe: Village of the Rainwind. Her last novel, A Bewitched Crossroad (1984), is historical, set in 19th-century Botswana. She had also written a story of two prophets, one wealthy and one who lived poorly, called Jacob: The Faith-Healing Priest.[137][138]

The 1981 comedy The Gods Must Be Crazy was set in Botswana and became a major international hit; 2000's Disney production Whispers: An Elephant's Tale was filmed in Botswana. In 2009, parts of M. Saravanan's Tamil-language Indian action film Ayan were filmed in Botswana.

The critically acclaimed A United Kingdom, about the real-life love story of Seretse Khama and Ruth Williams, was filmed partly between Botswana and London, and was released internationally in 2016.[139]

Media

There are six television stations in Botswana, one of which is state-owned (Botswana TV), along with Now TV, Khuduga HD, Maru TV, Access TV and EBotswana. There are five local radio stations (RB1, RB2, Duma FM, Gabz FM, and Yarona FM) and thirteen newspapers (Mmegi, Sunday Standard, The Telegraph, Business Weekly, The Botswana Gazette, The Voice, The Guardian, Echo, Botswana People's Daily, DailyNews, Tswana Times, Weekend Post, and The Monitor) that publish regularly.

Music

Botswana's music is mostly vocal and performed, sometimes without drums depending on the occasion; it also makes heavy use of string instruments. Botswana folk music has instruments such as setinkane (a sort of miniature piano), segankure/segaba (a Botswanan version of the Chinese instrument erhu), moropa (meropa -plural) (many varieties of drums), phala (a whistle used mostly during celebrations, which comes in a variety of forms). Botswanan cultural musical instruments are not confined only to the strings or drums. The hands are used as musical instruments too, by either clapping them together or against phathisi (goat skin turned inside out wrapped around the calf area, only used by men) to create music and rhythm. For the last few decades, the guitar has been celebrated as a versatile music instrument for Tswana music as it offers a variety in string which the segaba instrument does not have. The national anthem is "Fatshe leno la rona". Written and composed by Kgalemang Tumediso Motsete, it was adopted upon independence in 1966.[140][141][142]

Visual arts

In the northern part of Botswana, women in the villages of Etsha and Gumare are noted for their skill at crafting baskets from Mokola Palm and local dyes. The baskets are generally woven into three types: large, lidded baskets used for storage, large, open baskets for carrying objects on the head or for winnowing threshed grain, and smaller plates for winnowing pounded grain. The artistry of these baskets is being steadily enhanced through colour use and improved designs as they are increasingly produced for international markets.[143]

The oldest paintings from both Botswana and South Africa depict hunting, animal and human figures, and were made by the Khoisan (!Kung San/Bushmen) over twenty thousand years ago within the Kalahari Desert.

Food

The cuisine of Botswana mostly includes meat as Botswana is a cattle country. The national dish is seswaa, pounded meat made from goat meat or beef, Segwapa dried, cured meat ranging from beef to game meats & the cut may also vary, either fillets of meat cut into strips following the grain of the muscle, or flat pieces sliced across the grain. Botswana's cuisine shares some characteristics with other cuisine of Southern Africa.

Examples of Botswana food are: Bogobe, pap (maize porridge), boerewors, samp, Magwinya (fried dough bread) and mopane worms. Porridge (bogobe) is made by putting sorghum, maize, or millet flour into boiling water, stirring into a soft paste, and cooking it slowly. A dish called ting is made when the sorghum or maize is fermented, and milk and sugar added. Without the milk and sugar, ting is sometimes eaten with meat or vegetables as lunch or dinner. Another way of making bogobe is to add sour milk and a cooking melon (lerotse). This dish is called tophi by the Kalanga tribe. Madila is a traditional fermented milk product similar to yogurt or sour cream.[144]

Many different kinds of beans are grown, including cowpeas, ditloo, and letlhodi. Some vegetables grow in the wild and are available seasonally including thepe and Delele (okra). Many fruits are locally available, including marula. Watermelons, believed to have come originally from Botswana, are plentiful in season. Another kind of melon, called lerotse or lekatane, is also grown. Some kinds of wild melon found in sandy desert areas are an important food and water source for the people who live in those areas. Kgalagadi Breweries Limited produces the national beer, St. Louis Lager, Botswana's first and only local beer brand that has also been a part of Botswana's rich history since 1989, and non-alcoholic beverage Keone Mooka Mageu, a traditional fermented porridge.

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in Botswana, with qualification for the 2012 Africa Cup of Nations being the national team's highest achievement to date. Other popular sports are softball, cricket, tennis, rugby, badminton, handball, golf, and track and field.[145][146] Botswana is an associate member of the International Cricket Council. Botswana became a member of The International Badminton Federation and Africa Badminton Federation in 1991. The Botswana Golf Union has an amateur golf league in which golfers compete in tournaments and championships. Botswana won the country's first Olympic medal in 2012 when runner Nijel Amos won silver in the 800 metres. In 2011, Amantle Montsho became world champion in the 400 metres and won Botswana's first athletics medal at the world level. High jumper Kabelo Kgosiemang is a three-time African champion, Isaac Makwala is a sprinter who specialises in the 400 metres, he was the gold medalist at the Commonwealth Games in 2018, Baboloki Thebe was a silver medalist in the 200 metres at the 2014 Summer Youth Olympics and reached the semi-finals at the 2014 World Junior Championships in Athletics, and Ross Branch Ross, a motor-biker, holds the number one plate in the South African Cross Country Championship and has competed at the Dakar Rally. Letsile Tebogo set the world junior record in the 100 metres with a time of 9.94 at the 2022 World Athletics Championships.

On 7 August 2021 Botswana won the bronze medal in the Men's 4 × 400 metres relay at the Olympics in Tokyo.

The card game bridge has a strong following; it was first played in Botswana around 40 years ago, and it grew in popularity during the 1980s. Many British expatriate schoolteachers informally taught the game in Botswana's secondary schools. The Botswana Bridge Federation (BBF) was founded in 1988 and continues to organise tournaments. Bridge has remained popular and the BBF has over 800 members.[147] In 2007 the BBF invited the English Bridge Union to host a week-long teaching programme in May 2008.[148]

Education

Botswana has made great strides in educational development since independence in 1966. At that time there were very few graduates in the country and only a very small percentage of the population attended secondary school. Botswana increased its adult literacy rate from 69% in 1991 to 83% in 2008.[149] Among sub-Saharan African countries, Botswana has one of the highest literacy rates.[150] According to The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency as of 2015, 88.5% of the population age 15 and over could read and write and were respectively literate.[150]

With the discovery of diamonds and the increase in government revenue that this brought, there was a huge increase in educational provision in the country. All students were guaranteed ten years of basic education, leading to a Junior Certificate qualification. Approximately half of the school population attends a further two years of secondary schooling leading to the award of the Botswana General Certificate of Secondary Education (BGCSE). Secondary education in Botswana is neither free nor compulsory.

After leaving school, students can attend one of the seven technical colleges in the country, or take vocational training courses in teaching or nursing. Students enter the University of Botswana, Botswana University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Botswana International University of Science and Technology and the Botswana Accountancy College in Gaborone. Many other students end up in the numerous private tertiary education colleges around the country. Notable among these is Botho University, the country's first private university which offers undergraduate programs in Accounting, Business and Computing. Another international university is the Limkokwing University of Creative Technology which offers various associate degrees in Creative Arts.[151] Other tertiary institutions include Ba Isago, ABM University College the largest school of business and management, New Era, Gaborone Institute of Professional Studies, Gaborone University College of Law And Professional Studies etc. Tremendous strides in providing quality education have been made by private education providers such that a large number of the best students in the country are now applying to them as well. A vast majority of these students are government sponsored. The nation's second international university, the Botswana International University of Science and Technology, was completed in Palapye in 2011.

The quantitative gains have not always been matched by qualitative ones. Primary schools in particular still lack resources, and the teachers are less well paid than their secondary school colleagues. The Botswana Ministry of Education[152] is working to establish libraries in primary schools in partnership with the African Library Project.[153] The Government of Botswana hopes that by investing a large part of national income in education, the country will become less dependent on diamonds for its economic survival, and less dependent on expatriates for its skilled workers.[154] Those objectives are in part pursued through policies in favour of vocational education, gathered within the NPVET (National Policy on Vocational Education and Training), aiming to "integrate the different types of vocational education and training into one comprehensive system".[154] Botswana invests 21% of its government spending in education.[149]

In January 2006, Botswana announced the reintroduction of school fees after two decades of free state education[155] though the government still provides full scholarships with living expenses to any Botswana citizen in university, either at the University of Botswana or if the student wishes to pursue an education in any field not offered locally, they are provided with a full scholarship to study abroad.

Science and technology

Botswana is planning to use science and technology to diversify its economy and thereby reduce its dependence on diamond mining. To this end, the government has set up six hubs since 2008, in the agriculture, diamonds, innovation, transport, health and education sectors.[156]

Botswana published its updated National Policy on Research, Science and Technology in 2011, within a UNESCO project sponsored by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation and Development (AECID). This policy aims to take up the challenges of rapid technological evolution, globalisation and the achievement of the national development goals formulated in high-level strategic documents that include Botswana's Tenth National Development Plan to 2016 and Vision 2016.[156] The National Policy on Research, Science, Technology and Innovation (2011) fixes the target of raising gross domestic expenditure on research and development (R&D) from 0.26% of GDP in 2012 to over 2% of GDP by 2016. This target can only be reached within the specified time frame by raising public spending on R&D.[156]

Despite the modest level of financial investment in research, Botswana counts one of the highest researcher densities in sub-Saharan Africa: 344 per million inhabitants (in head counts), compared to an average of 91 per million inhabitants for the subcontinent in 2013.[156] Botswana was ranked 85th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[157][158]

In 2009, Botswana-based company Deaftronics launched a solar-powered hearing aid after six years of prototype development. Since then, Deaftronics has sold over 10,000 of the hearing aids. Priced at $200 per unit, each hearing aid includes four rechargeable batteries (lasting up to three years) and a solar charger for them. The product is inexpensive compared to many similar devices, that can start from around $600.[159][160]

In 2011, Botswana's Department of Agricultural Research (DAR) unveiled Musi cattle, designed to ultimately optimise the overall efficiency for beef production under Botswana conditions. A hybrid of Tswana, Bonsmara, Brahman, Tuli and Simmental breeds,[161] it is hoped that the composite will lead to increased beef production. The objective of the research was to find a genetic material that could perform like crossbreeds already found in Botswana and well above the indigenous Tswana breed while retaining the hardiness and adaptability of the native stock in one package.[162]

In 2016, the Botswana Institute of Technology Research and Innovation (BITRI) developed a rapid testing kit for foot-and-mouth disease in collaboration with the Botswana Vaccine Institute and Canadian Food Inspection Agency. The existing diagnostic methods required highly trained laboratory personnel and special equipment, which caused delays in the implementation of control procedures; whereas the kit developed in Botswana allows for on-site diagnosis to be made.[163]

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) (MeerKAT) will consist of thousands of dishes and antennas spread over large distances linked together to form one giant telescope. Additional dishes will be located in eight other African countries Botswana among them. Botswana was selected to participate because of its ideal location in the southern hemisphere and environment, which could enable easier data collection from the universe. Botswana government has built SKA precursor telescope at Kgale View, called the African Very Long Base Line Interferometry Network (AVN) & sent student on Astronomy scholarships.[164]

Botswana launched its own 3-year programme to build & launch a Micro Satellite (CubeSat) Botswana Satellite Technology (Sat-1 Project) in Gaborone on 18 December 2020. The development of the satellite will be led by Botswana International University of Science and Technology (BIUST) with technical support from University of Oulu in Finland and Loon, a giant leap forward in the realisation of Botswana's ambition to become a technologically driven economy. The satellite, which will be used for earth observation, will generate data for smart farming and real-time virtual tourism. Furthermore, it will help us predict and forecast harvest time through the use of robotics and automated technology.[165][166]

In the IT sector in 2016 a firm, Almaz, opened a first-of-its-kind computer assembly company.[167][168] Ditec, a Botswana company, also customises, designs and manufactures mobile phones. Ditec is one of the leading experts in design, development and customisation of Microsoft powered devices.[169]

On 19 November 2021 scientists at the Botswana Harvard HIV Reference Laboratory (BHHRL) first discovered the variant Omicron subsequently designated B.1.1.529, and then named "Omicron" becoming the first country in the world to discover the variant. Since early 2021, they have genome-sequenced some 2,300 positive SARS-CoV-2 virus samples. According to Dr Gaseitsiwe, Botswana's genome sequence submissions to GISAID are among the highest in the African region on a per capita basis, on a par with its well-resourced neighbour South Africa. Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership (BHP) was built in 2003, two years after the umbrella organisation opened the BHHRL, its purpose-built HIV research lab and one of the first on the continent.[170]

Infrastructure

Botswana has 971 kilometres (603 mi) of railway lines, 18,482 kilometres (11,484 mi) of roads, and 92 airports, of which 12 have paved runways. The paved road network has almost entirely been constructed since independence in 1966. The national airline is Air Botswana, which flies domestically and to other countries in Africa. Botswana Railways is the national railway company, which forms a crucial link in the Southern African regional railway system. Botswana Railways offers rail-based transport facilities for moving a range of commodities for the mining sector and primary industries, as well as passenger-train services and dry ports.[171][172]

In terms of power infrastructure in Botswana, the country produces coal for electricity and oil is imported into the country. Recently, the country has taken a large interest in renewable energy sources and has completed a comprehensive strategy that will attract investors in the wind, solar and biomass renewable energy industries. Botswana's power stations include Morupule B Power Station (600 MW), Morupule A Power Station (132 MW), Orapa Power Station (90 MW), Phakalane Power Station (1.3 MW) and Mmamabula Power Station (300 MW), which is expected to be online in the near future. A 200 MW solar power plant is at the planning and design stage by Ministry of Mineral Resources, Green Technology and Energy Security.[173][174]

Health

Botswana's healthcare system has been steadily improving and expanding its infrastructure to become more accessible. The country's position as an upper middle-income country has allowed them to make strides in universal healthcare access for much of Botswana's population. The majority of the Botswana's 2.3 million inhabitants now live within five kilometres of a healthcare facility.[175] As a result, the infant mortality and maternal mortality rates have been on a steady decline.[176] The country's improving healthcare infrastructure has also been reflected in an increase of the average life expectancy from birth, with nearly all births occurring in healthcare facilities.[175]

Access to healthcare has not alleviated all of the country's healthcare concerns because, like many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Botswana is still battling high rates of HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases. In 2013, about 25% of the population was infected with HIV/AIDS.[177] Botswana is also grappling with high rates of malnutrition among children under the age of 5 which has led to other health concerns such as diarrhea and stunted growth.[178]Health industry

The Ministry of Health[179] in Botswana is responsible for overseeing the quality and distribution of healthcare throughout the country. Life expectancy at birth was 55 in 2009 according to the World Bank, having previously fallen from a peak of 64.1 in 1990 to a low of 49 in 2002.[180] After Botswana's 2011 census, current life expectancy is estimated at 54.06 years.[2]

The Cancer Association of Botswana is a voluntary non-governmental organisation. The association is a member of the Union for International Cancer Control. The Association supplements existing services through provision of cancer prevention and health awareness programs, facilitating access to health services for cancer patients and offering support and counselling to those affected.[181]

HIV/AIDS epidemic

Like elsewhere in Sub-Saharan Africa, the economic impact of AIDS is considerable. Economic development spending was cut by 10% in 2002–3 as a result of recurring budget deficits and rising expenditure on healthcare services. Botswana has been hit very hard by the AIDS pandemic; in 2006 it was estimated that life expectancy at birth had dropped from 65 to 35 years.[182] However, after Botswana's 2011 census current life expectancy is estimated at 54.06 years.[2] However the graph here shows over 65 years, therefore there is conflicting information about life expectancy.

The prevalence of HIV/AIDS in Botswana was estimated at 25.4% for adults aged 15–49 in 2009 and 21.9% in 2013,[25]: A8 exceeded by Lesotho and Eswatini in sub-Saharan African nations. This places Botswana at the third highest prevalence in the world, in 2013, while "leading the way in prevention and treatment programmes".[26] In 2003, the government began a comprehensive programme involving free or cheap generic antiretroviral drugs as well as an information campaign designed to stop the spread of the virus; in 2013, over 40% of adults in Botswana had access to antiretroviral therapy.[25]: 28 In the age group of 15–19 years old, prevalence was estimated at 6% for females and 3.5% for males in 2013,[25]: 33 and for the 20–24 age group, 15% for females and 5% for males.[25]: 33 Botswana is one of 21 priority countries identified by the UN AIDS group in 2011 in the Global Plan to eliminate new HIV infections among children and to keep their mothers alive.[25]: 37 From 2009 to 2013, the country saw a decrease over 50% in new HIV infections in children.[25]: 38 A further measure of the success, or reason for hope, in dealing with HIV in Botswana, is that less than 10% of pregnant HIV-infected women were not receiving antiretroviral medications in 2013, with a corresponding large decrease (over 50%) in the number of new HIV infections in children under 5.[25]: 39, 40 Among the UN Global Plan countries, people living with HIV in Botswana have the highest percentage receiving antiretroviral treatment: about 75% for adults (age 15+) and about 98% for children.[25]: 237

With a nationwide Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission program, Botswana has reduced HIV transmission from infected mothers to their children from about 40% to just 4%. Under the leadership of Festus Mogae, the Government of Botswana solicited outside help in fighting HIV/AIDS and received early support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Merck Foundation, and together formed the African Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Partnership (ACHAP). Other early partners include the Botswana-Harvard AIDS Institute, of the Harvard School of Public Health and the Botswana-UPenn Partnership of the University of Pennsylvania. According to the 2011 UNAIDS Report, universal access to treatment – defined as 80% coverage or greater – has been achieved in Botswana.[183]

Tourism

The Botswana Tourism Organisation[184] is the country's official tourism group. Primarily, tourists visit Gaborone due to the city having numerous activities for visitors. The Lion Park Resort[185] is Botswana's first permanent amusement park and hosts events such as birthday parties for families. Other destinations in Botswana include the Gaborone Yacht Club and the Kalahari Fishing Club and natural attractions such as the Gaborone Dam and Mokolodi Nature Reserve. There are golf courses which are maintained by the Botswana Golf Union (BGU).[186] The Phakalane Golf Estate is a multi-million-dollar clubhouse that offers both hotel accommodations and access to golf courses. Museums in Botswana include:

- Botswana National Museum in Gaborone

- Kgosi Bathoen II (Segopotso) Museum in Kanye

- Kgosi Sechele I Museum in Molepolole

- Khama III Memorial Museum in Serowe

- Nhabe Museum in Maun

- Phuthadikobo Museum in Mochudi

- Supa Ngwano Museum Centre in Francistown

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 "About Our Country". Gov.bw. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

Botswana has a number of tribes across the country, collectively known as Batswana. The official language is English and Setswana is the national language, although there are other spoken languages.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Botswana". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 16 April 2014. (Archived 2014 edition)

- ↑ "Botswana". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. 14 September 2022. (Archived 2022 edition)

- ↑ "Botswana". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 17 December 2019. (Archived 2019 edition)

- ↑ Selolwane, Onalenna (2002). "Monopoly Politikos: How Botswana's Opposition Parties Have Helped Sustain One-Party Dominance". African Sociological Review. 6 (1): 68–90. doi:10.4314/asr.v6i1.23203. JSTOR 24487673.

- ↑ "Masisi to Lead Botswana as Khama Steps Down After a Decade". Bloomberg.com. 28 March 2018. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ↑ Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015 – Country Report – Botswana (PDF). fao.org (Report). United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. 2015. p. 9.

Total Country Area ('000)ha / 58 173

- ↑ "Botswana". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ↑ "Statistics Bostwana - Census 2023 - Population of cities, towns and villages" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Botswana)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ↑ "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". World Bank. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- 1 2 Human Development Report 2021-22: Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping our Future in a Transforming World (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. pp. 272–276. ISBN 978-9-211-26451-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Chapter: 01:04 (20 July 1984). "Interpretation Act 1984 (§40(1))". Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Botswana". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ↑ Darwa, P. Opoku (2011). Kazungula Bridge Project (PDF). African Development Fund. p. Appendix IV. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ "Population, total - Botswana | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ↑ "Botswana", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 28 March 2023, retrieved 5 April 2023

- ↑ Maundeni, Zibani; Mpabanga, Dorothy; Mfundisi, Adam (1 January 2007). "Consolidating Democratic Governance in Southern Africa : Botswana". Africa Portal. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ↑ "Bechuanaland was the former name of Botswana". generalknowledgefacts.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ↑ "overview of CPI indices". Transparency International. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ↑ Gross national income (GNI) – Nations Online Project Archived 19 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Nationsonline.org. Retrieved on 27 October 2016.

- ↑ Releases, Forbes Press. "Inaugural Forbes Under 30 Summit Africa To Take Place In Botswana In April 2022". Forbes. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ Rollnick, Roman (September 2002). "Botswana's high-stakes assault on AIDS". Africa Renewal. United Nations. 16 (10): 6–9. PMID 12458550. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ↑ Powell, Alvin (16 April 2009). "Mogae shifts stress to HIV prevention". Harvard Gazette. Harvard University. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "The Gap Report" (PDF). Geneva: UN AIDS. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- 1 2 "HIV and Aids in Botswana". Avert International Aids Charity. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ↑ "Botswana is first country with severe HIV epidemic to reach key milestone in the elimination of mother-to-child HIV transmission". Brazzaville: UN AIDS. 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ↑ "Partnership for Success: CDC and Botswana Lead Progress Toward HIV Epidemic Control". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 30 September 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ↑ "Botswana". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 15 May 2007. (Archived 2007 edition)

- ↑ Monaka, Kemmonye Collete; Chebanne, Anderson Monthusi (2019). "Setswana and the Building of a Nation State". Anthropological Linguistics. 61 (1): 75–93. ISSN 0003-5483. JSTOR 26907070.

- ↑ Bolaane, Maitseo; Mgadla, Part Themba (1997). Batswana. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 1. ISBN 9780823920082.

- ↑ "Botswanan or Batswana? It's complicated – Voices of Africa". Voices of Africa. 17 August 2015. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ↑ Morton, F.; Ramsay, J. and Mgadla, T. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Botswana. Scarecrow Press, p. 34; ISBN 9780810854673

- ↑ Chan, Eva KF; Timmermann, Axel; Baldi, Benedetta F.; Moore, Andy E.; Lyons, Ruth J.; Lee, Sun-Seon; Kalsbeek, Anton MF; Petersen, Desiree C.; Rautenbach, Hannes; Förtsch, Hagen EA; Bornman, MS Riana; Hayes, Vanessa M. (28 October 2019). "Human origins in a southern African palaeo-wetland and first migrations". Nature. Nature Research. 575 (7781): 185–189. Bibcode:2019Natur.575..185C. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1714-1. PMID 31659339. S2CID 204946938. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ↑ Woodward, Aylin (29 October 2019). "Every person alive today descended from a woman who lived in modern-day Botswana about 200,000 years ago, a new study finds". Business Insider. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ↑ Staurset, S.; Coulson, S. (2014). "Sub-surface movement of stone artefacts at White Paintings Shelter, Tsodilo Hills, Botswana: Implications for the Middle Stone Age chronology of central southern Africa". Journal of Human Evolution. 75: 153–65. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.04.006. PMID 24953669.

- ↑ Wilmsen, E. (1989) Land Filled With Flies: A Political Economy of the Kalahari. Chicago: Chicago University Press, pp. 71–5. ISBN 9780226900155

- ↑ Denbow, James (1986). "A New Look at the Later Prehistory of the Kalahari". The Journal of African History. 27 (1): 3–28. doi:10.1017/S0021853700029170. JSTOR 181334. S2CID 163079138.

- ↑ Denbow, James; Klehm, Carla; Dussubieux, Laure (April 2015). "The glass beads of Kaitshàa and early Indian Ocean trade into the far interior of southern Africa". Antiquity. 89 (344): 361–377. doi:10.15184/aqy.2014.50. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 161212483.

- 1 2 Hall, Martin (1990), Farmers, Kings, and Traders: The People of Southern Africa, 200-1860, University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-31326-3.

- ↑ Magang, D. (2008) The Magic of Perseverance: The Autobiography of David Magang. Cape Town: CASAS, pp. 10–14; ISBN 9781920287702

- ↑ Tlou, T. (1974). "The Nature of Batswana States: Towards a Theory of Batswana Traditional Government – The Batawana Case". Botswana Notes and Records. 6: 57–75. ISSN 0525-5090. JSTOR 40959210.

- ↑ Morton, Fred. "The Rise of a Raiding State: Makaba II's Ngwaketse, 1780–1824".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Morton, B. (1993). "Pre-1904 Population Estimates of the Tswana". Botswana Notes and Records. 25: 89–99. JSTOR 40979984.

- ↑ Morton, Barry (14 January 2009). "The Hunting Trade and the Reconstruction of Northern Tswana Societies after the Difaqane, 1838–1880". South African Historical Journal. 36: 220–239. doi:10.1080/02582479708671276.

- ↑ Morton, Barry (1997). "The Hunting Trade and the Reconstruction of Northern Tswana Societies after the Difaqane, 1838–1880". South African Historical Journal. 36: 220–239. doi:10.1080/02582479708671276.

- ↑ timestamp 45:20

- ↑ Magang, D. (2008) The Magic of Perseverance: The Autobiography of David Magang. Cape Town: CASAS, pp. 28–38. ISBN 9781920287702

- ↑ Ramsay, J. (1991). "The Botswana-Boer War of 1852–53: How the Batswana Achieved Victory". Botswana Notes and Records. 23: 193–208. JSTOR 40980851.

- ↑ Ramsay, Jeff. "Mmegi Blogs :: The Guns of Khutiyabasadi (II)". Mmegi Blogs. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ↑ Landau, P. (1995) The Realm of the Word: Language, Gender, and Christianity in the Southern African Kingdom. Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann.

- ↑ Morton, Barry; Ramsay, Jeff. "The Invention and Perpetuation of Botswana's National Mythology, 1885–1966". pp. 4–7. Retrieved 13 July 2018 – via academia.edu.

- ↑ "Warren informed Chiefs Bathoen of Bangwaketse, Khama of Bangwato and Sebele of Bakwena about the protection in May 1885 (Mogalakwe, 2006)." (from T.E. Malebeswa (2020): Tribal Territories Act, indirect rule, chiefs and subjects)

- ↑ Morton, Barry; Ramsay, Jeff. "The Invention and Perpetuation of Botswana's National Mythology, 1885–1966". pp. 7–11. Retrieved 13 July 2018 – via academia.edu.

- ↑ Parsons, N. (1998) King Khama, Emperor Joe, and the Great White Queen: Victorian Britain Through African Eyes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Hayes, Frank (1980). "South Africa's Departure from the Commonwealth, 1960–1961". The International History Review. 2 (3): 453–484. doi:10.1080/07075332.1980.9640222. ISSN 0707-5332. JSTOR 40105085.

- 1 2 "Botswana: Late British colonialism (1945–1966)". eisa.org. Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ "U.K.: Bechuanaland independence conference opens in London 1966". British Pathé historical collection.

- ↑ "Fireworks at Midnight". Britishempire.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ↑ "Botswana country profile". BBC News. 3 April 2018.

- ↑ "Namibia General Information". Southern-eagle.com. 21 March 1990. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ↑ Mineral Facts and Problems (1975 ed.). United States Bureau of Mines. 1975. p. 329. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ↑ "Botswana's Diamond Mines". NASA Earth Observatory. 14 October 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ↑ "Mining & Minerals". International Trade Administration. 2 August 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ↑ Guest, Peter (3 December 2015). "Inside the world's richest diamond mine". CNN. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Darkoh" (PDF). IS: Rala. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Botswana, US sign 'Debt-for-Nature' agreement". Afrol. Archived from the original on 1 December 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ "NOTCDIB" (PDF). UNCCD. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2010.