| |

| Full name | Team Lotus |

|---|---|

| Base | Hethel, Norfolk, United Kingdom |

| Founder(s) | Colin Chapman |

| Noted staff | Maurice Philippe Peter Collins Peter Wright Peter Warr Mike Costin Keith Duckworth Gérard Ducarouge Frank Dernie Chris Murphy Andrew Ferguson |

| Noted drivers | |

| Formula One World Championship career | |

| First entry | 1958 Monaco Grand Prix |

| Races entered | 491 (489 starts) |

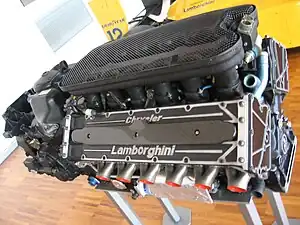

| Engines | Climax, BRM, Ford, Pratt & Whitney, Renault, Honda, Judd, Lamborghini, Mugen-Honda |

| Constructors' Championships | 7 (1963, 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, 1973, 1978) |

| Drivers' Championships | 6 (1963, 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, 1978) |

| Race victories | 74 |

| Podiums | 165 |

| Pole positions | 102 |

| Fastest laps | 65 |

| Final entry | 1994 Australian Grand Prix |

| Formula One World Championship career | |

|---|---|

| Engines | Borgward, Coventry Climax, BRM, Maserati, Ford-Cosworth, Pratt & Whitney, Renault, Honda, Judd, Lamborghini, Mugen-Honda |

| Entrants | Team Lotus, Rob Walker Racing Team, numerous minor teams and privateers |

| First entry | 1958 Monaco Grand Prix |

| Last entry | 1994 Australian Grand Prix |

| Races entered | 491 entries (489 starts) |

| Race victories | 79 |

| Constructors' Championships | 7 (1963, 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, 1973, 1978) |

| Drivers' Championships | 6 (1963, 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, 1978) |

| Pole positions | 107 |

| Fastest laps | 71 |

Team Lotus was the motorsport sister company of English sports car manufacturer Lotus Cars. The team ran cars in many motorsport categories including Formula One, Formula Two, Formula Ford, Formula Junior, IndyCar, and sports car racing. More than ten years after its last race, Team Lotus remained one of the most successful racing teams of all time, winning seven Formula One Constructors' titles, six Drivers' Championships, and the Indianapolis 500 in the United States between 1962 and 1978. Under the direction of founder and chief designer Colin Chapman, Lotus was responsible for many innovative and experimental developments in critical motorsport, in both technical and commercial arenas.

The Lotus name returned to Formula One in 2010 as Tony Fernandes's Lotus Racing team. In 2011, Team Lotus's iconic black-and-gold livery returned to F1 as the livery of the Lotus Renault GP team, sponsored by Lotus Cars, and in 2012 the team was re-branded completely as Lotus F1 Team.

1950s – Lotus's origins

Colin Chapman established Lotus Engineering Ltd in 1952 at Hornsey, UK. Lotus achieved rapid success with the 1953 Mk 6 and the 1954 Mk 8 sports cars. Team Lotus was split off from Lotus Engineering in 1954.[1] A new Formula Two regulation was announced for 1957, and in Britain, several organizers ran races for the new regulations during the course of 1956. Most of the cars entered that year were sports cars, and they included a large number of Lotus 11s, the definitive Coventry Climax-powered sports racer, led by the Team Lotus entries for Chapman, driven by Cliff Allison and Reg Bicknell.

The following year, the Lotus 12 appeared. Driving one in 1958, Allison won the F2 class in the International Trophy at Silverstone, beating Stuart Lewis-Evans's Cooper. The remarkable Coventry Climax-powered Type 14, the Lotus Cars production version of which was the original Lotus Elite, won six class victories, plus the "Index of Performance" several times at the 24 Hours of Le Mans race.

As the Coventry Climax engines were enlarged in 1952 to 2.2-litres, Chapman decided to enter Grand Prix racing, running a pair of Lotus 12s at Monaco in 1958 for Graham Hill and Cliff Allison. These were replaced later that year by Lotus 16s.

In 1959 – by which time the Coventry Climax engines had been stretched to 2.5-litres inline with Formula rules – Chapman continued with front-engined F1 cars, but achieved little, so in 1960 Chapman switched to the milestone mid-engined Lotus 18. By then, the company's success had caused it to expand to such an extent that it had to move to new premises at Cheshunt.

Domination in 1960s and 1970s

The first Formula One victory for Team Lotus came when Innes Ireland won the 1961 United States Grand Prix. A year earlier, Stirling Moss had recorded the first victory for a Lotus car at Monaco in his Lotus 18 entered by the independent Rob Walker Racing Team.

There were successes in Formula Two and Formula Junior. The road car business was doing well with the Lotus Seven and the Lotus Elite and this was followed by the Lotus Elan in 1962. More racing success followed with the 26R, the racing version of the Elan, and in 1963 with the Lotus Cortina, which Jack Sears drove to the British Saloon Car Championship title, a feat repeated by Jim Clark in 1964 and Alan Mann in the 1965 European Touring car Championship.

1966Aug.jpg.webp)

In 1963, Clark drove the Lotus 25 to a remarkable seven wins in the season and won the World Championship. The 1964 title was still for the taking by the time of the last race in Mexico but problems with Clark's Lotus and Hill's BRM gave it to Surtees in his Ferrari. However, in 1965, Clark dominated again, six wins in his Lotus 33 gave him the championship.

While very innovative, Chapman also came under criticism for the structural fragility of his designs. The number of top drivers seriously injured or killed in Lotus machinery was considerable – notably Stirling Moss, Alan Stacey, Mike Taylor, Jim Clark, Mike Spence, Bobby Marshman, Graham Hill, Jochen Rindt and Ronnie Peterson. In Dave Friedman's book "Indianapolis Memories 1961–1969", Dan Gurney is quoted as saying, "Did I think the Lotus way of doing things was good? No. We had several structural failures in those cars [Indianapolis Lotus 34 and 38]. But at the time, I felt it was the price you paid for getting something significantly better."

When the Formula One engine size increased to three litres in 1966, Lotus was caught unprepared partly because of the surprising failure of the Coventry Climax 1.5-Litre FWMW Flat-16 project, which prevented Climax from developing a 3-Litre successor. They started the season fielding the hastily prepared and uncompetitive two-litre Coventry-Climax FWMV V8 engine, only switching to the BRM P75 H16 engine in time for the Italian Grand Prix, with the new engine proving to be overweight and unreliable. A switch to the new Ford Cosworth DFV, designed by former Lotus employee Keith Duckworth, in 1967 returned the team to winning form.

Although they failed to win the title in 1967, by the end of the season, the Lotus 49 and the DFV engine were mature enough to make the Lotus team dominant again. However, for 1968 Lotus had lost its exclusive right to use the DFV. The season-opening 1968 South African Grand Prix confirmed Lotus's superiority, with Jim Clark and Graham Hill finishing 1–2. It would be Clark's last win. On 7 April 1968, Clark, one of the most successful and popular drivers of all time, was killed driving a Lotus 48 at Hockenheimring in a non-championship Formula Two event. The season saw the introduction of wings as seen previously on various cars, including the Chaparral sports car. Colin Chapman introduced modest front wings and a spoiler on Hill's Lotus 49B at the 1968 Monaco Grand Prix. Graham Hill won the F1 World Championship in 1968 driving the Lotus 49.

Around the same time, Chapman moved Lotus to new premises at Hethel in Norfolk. A new factory was built on the site, the former RAF Hethel bomber base, and the old runways were converted into a testing facility. The offices and design studios were based at nearby Ketteringham Hall, which became the headquarters of both Team Lotus and Lotus Cars. Additional car testing was carried out at Snetterton, a few miles from Hethel.

In 1969, the team spent a lot of time experimenting with a gas turbine powered car, and, after four wet races in 1968, with four wheel drive. Both were unsuccessful, especially as every race was dry. They penned a revolutionary new car for 1970 – the wedge-shaped Lotus 72.

The new Lotus 72 was a very innovative car, featuring torsion bar suspension, hip-mounted radiators, inboard front brakes and an overhanging rear wing. The 72 originally had suspension problems, and Jochen Rindt took a lucky victory in Monaco in the old 49 when Jack Brabham crashed on the last lap while leading. But when antidive and antisquat were designed out of the suspension, the car quickly showed its superiority, and Rindt dominated the championship until he was killed at Monza when a brake shaft broke. Rindt had only recently begun to wear a shoulder harness, but refused to wear crotch straps because he felt they slowed his exit from the car in the event of fire. When the car hit the barrier head-on, Rindt submarined forward and the lap belt inflicted fatal head and neck injuries.

The rest of the 1970 season was nailbiting, as Ferrari closed in on Rindt's undefended lead. A brilliant victory in the US GP by rookie driver Emerson Fittipaldi, who had made his debut in the British GP in a 49, sealed the championship for Rindt, who became the only man in history to win the world championship posthumously.

Lotus's 1971 experiments did not bring any serious advance in technology, but allowed Chapman to test several drivers. For 1972, the team focused again on the type 72 chassis, with Imperial Tobacco continuing its sponsorship of the team under its new John Player Special brand. The cars, now often referred to as 'JPS', were fielded in a new black and gold livery – a new brand developed to make the most of the promotional power of motorsport. Lotus took the championship by surprise in 1972 with 25-year-old Brazilian driver Emerson Fittipaldi, who became at the time the youngest world champion, a distinction he held until 2005, when 24-year-old Fernando Alonso took the accolade. Team Lotus also won the F1 World Championship for Manufacturers for a sixth time in 1973. The 72 raced in Formula 1 for five years, proving to be more successful than its supposed replacement, the Lotus 76. It was finally retired at the end of the 1975 season, as the Lotus 77 was prepared for the 1976 season.

The first-ever Formula Ford car was built around a Formula 3 Lotus, the Type 51.

Chapman was also successful at Indianapolis with the Lotus 29, almost winning the 500 at its first attempt in 1963 with Clark at the wheel. The race marked the beginning of the end for the old front-engined Indianapolis roadsters. Clark was leading when he retired from the 1964 event with suspension failure, but in 1965, he won the biggest prize in US racing driving his Lotus 38 and winning by a lap; it was the first mid-engined car to win the Indianapolis 500.

Many of Chapman's successes came from innovation. The Lotus 25 was the first monocoque chassis in F1, the 49 was the first car of note to use the engine as a stressed member, the Lotus 56 Indycar was powered by a gas turbine engine and was fitted with four-wheel drive, the Lotus 63 was the first mid-engined F1 car to race with four-wheel drive, and the 72 broke new ground in aerodynamics. Chapman was also an innovator as a team boss. For the 1968 season, the FIA decided to permit sponsorship after the withdrawal of support from automotive-related firms, such as BP, Shell and Firestone. In April, Team Lotus became the first works team (second only to Team Gunston entering a private Brabham car at the 1968 South African Grand Prix) to paint their cars in the livery of their sponsors, with Clark's Lotus 48 Formula Two car appearing at Hockenheim in the red, gold and white colors of Imperial Tobacco's Gold Leaf brand. The first Formula One car in this livery was Graham Hill's Lotus 49B car entered at the 1968 Spanish Grand Prix in Jarama.

Team Lotus as a constructor was first to achieve 50 Grand Prix victories. (Ferrari was the second to do so, having won their first Formula One race in 1951, seven years before the first Lotus F1 car.)

In the mid-to-late 1970s, Lotus experienced a resurgence with Mario Andretti joining the team. This came about the morning after the 1976 U.S. Grand Prix West at Long Beach, when Andretti's VPJ-Parnelli had proven uncompetitive. Bob Evans did not qualify his Lotus and Gunnar Nilsson, in the other Lotus 77, qualified 8th only to fall out with suspension failure before completing a lap. Chapman and Andretti ran into each other in a hotel coffee shop the morning after the race, and decided to join forces. Andretti's development expertise helped give new life to the then-moribund Lotus 77. Engineers began to investigate aerodynamic ground effects. The Lotus 78, and then the Lotus 79 of 1978 were extraordinarily successful, with Mario Andretti winning the F1 World Championship. Lotus attempted to take ground effects further with the Lotus 80 and Lotus 88. The team developed an all-carbon-fibre car, the Lotus 88, in 1981. The 88 was banned from racing for its 'twin chassis' technology where the driver had separate suspension from the aerodynamic parts of the car. McLaren's MP4/1 beat it as the first all-carbon-fibre car to race. Chapman was beginning work on an active suspension development programme when he died of a heart attack in December 1982 at the age of 54.

1980s

After Chapman's death, the racing team was continued by his widow, Hazel, and managed by Peter Warr,[2] but a series of F1 designs proved unsuccessful since then. Midway through 1983 Lotus hired French designer Gérard Ducarouge and, in five weeks, he built the Renault turbo powered 94T. A switch to Goodyear tyres in 1984 enabled Elio de Angelis to finish third in the World Championship, despite the fact that the Italian did not win a race. The team also finished in 3rd place in the Constructors' Championship.

When Nigel Mansell departed at the end of the year the team hired Ayrton Senna. The Lotus 97T scored victories with de Angelis at Imola and Senna in Portugal and Belgium. The team, although it had now won three races instead of none, lost 3rd in the Constructors' Championship to Williams (who beat them on countback with 4 wins). Senna scored eight pole positions, with two wins (Spain and Detroit) in 1986 driving the evolutionary Lotus 98T. Lotus regained 3rd in the Constructors' Championship, passing Ferrari. At the end of the year the team lost its long-time backing from John Player & Sons and found new sponsorship with Camel. Senna's skills attracted the attention of the Honda Motor Company and when Lotus agreed to run Satoru Nakajima as its second driver a deal for engines was agreed. The Ducarouge-designed 99T featured active suspension, but Senna was able to win just twice: at Monaco and Detroit, with the team again finishing 3rd in the Constructors' Championship, like the previous year behind British rivals Williams and McLaren, but ahead of Ferrari.

The Brazilian moved to McLaren in 1988, and Lotus signed Senna's countryman and then World Champion Nelson Piquet from Williams. Both Piquet and Nakajima failed to make any impressions in terms of fighting for victories. However the team still managed to finish 4th in the Constructors' Championship. Lotus showed in 1988 that it took more than a Honda engine to win races. 1988 was the year in which McLaren (with Senna and Alain Prost) won 15 of the season's 16 races with the same specification Honda engines as Lotus were using. The best results for the team were three 3rd places for Piquet in Brazil, San Marino and Australia. Lotus at times were hard-pressed fighting off the less powerful naturally-aspirated V8 cars during the season, and rarely challenged either McLaren or Ferrari.

The Lotus-Honda 100T was not a success and Ducarouge returned to France in mid-1989. Lotus hired Frank Dernie to replace him. With the new engine regulations in 1989, Lotus lost its turbocharged Honda engines and used the normally-aspirated Judd V8 instead. In the middle of the year Warr departed and was replaced as team manager by Rupert Manwaring, while long time Lotus senior executive Tony Rudd was brought in as chairman. The best results for the team in 1989 was 4th places for Piquet in the British, Canadian and Japanese races, and 4th place and fastest lap for Nakajima in Australia. At the end of the season Piquet left for Benetton, and Nakajima moved to Tyrrell.

1990s and demise

A deal was organized for Lamborghini V12 engines and Derek Warwick and Martin Donnelly were hired to drive for 1990. The Dernie design was not a success with Warwick scoring all the three points for a 6th in the 1990 Canadian Grand Prix and a 5th in the 1990 Hungarian Grand Prix; Donnelly was nearly killed in a violent accident at Jerez. At the end of the year Camel withdrew their sponsorship.

Former Team Lotus employees Peter Collins and Peter Wright organized a deal to take over the team from the Chapman family and in December the new Team Lotus was launched with Mika Häkkinen and Julian Bailey being signed for the 1991 season to drive updated Lotus 102Bs with Judd engines. At the 1991 San Marino Grand Prix, the team scored its first double points finish since the 1988 Brazilian Grand Prix, with Häkkinen in fifth and Bailey in sixth. Despite this, Bailey was soon replaced by Johnny Herbert for the balance of the season. For the following year, the team signed a deal to use Ford's HB V8 in their new Lotus 107s, designed by Chris Murphy. The team was now short on money and this affected performance, but the car allowed Häkkinen to score 11 points, including two fourth places at the 1992 French Grand Prix (where he had failed to qualify the previous year) and the 1992 Hungarian Grand Prix, while Herbert scored two points for 6th Places at the 1992 South African Grand Prix and 1992 French Grand Prix. The team finished 5th in the Constructors' Championship. Häkkinen, who finished 8th in the 1992 Drivers' Championship, moved to McLaren as a test driver in 1993. He was replaced by Alessandro Zanardi, who was himself replaced by Pedro Lamy after crashing heavily at the 1993 Belgian Grand Prix, where Herbert scored the last two points for Team Lotus. Over the year, the team scored 12 points despite the tight budget and finished 6th in the 1993 Constructors' Championship. Herbert finished 9th in the Drivers' Championship with three 4th placements: the 1993 Brazilian Grand Prix, where he lost 3rd to Benetton's Michael Schumacher shortly before the end of the race; the 1993 European Grand Prix, where he made only one pit stop for tyres; and the 1993 British Grand Prix, where he was not far behind Riccardo Patrese's 3rd placed Benetton at the end, having benefited from the retirements of Ayrton Senna, Martin Brundle and Damon Hill. Zanardi scored one 6th place at the 1993 Brazilian Grand Prix, the last race with both Lotus cars in the points.

Debts were mounting and the team was unable to develop the Lotus 107. For the 1994 season, the team gambled on success with Mugen Honda engines. Herbert and Lamy struggled on with the old car for the first few races. The Portuguese driver was seriously injured in an accident in testing at Silverstone and Zanardi returned. The team's new car, the Lotus 109, was introduced at the 1994 Spanish Grand Prix,[3] five races into the season, but only one car was available until the French Grand Prix two races later. In an effort to survive the team took on pay-driver Philippe Adams at the 1994 Belgian Grand Prix, but by the time of the Italian Grand Prix Zanardi was back in the car. Herbert qualified fourth in the 109, but at the first corner he was punted off by the Jordan of Eddie Irvine. Herbert later commented that he felt he could have won the race.[4] The following day the team applied for an Administration Order to protect itself from creditors. Tom Walkinshaw pounced and bought Johnny Herbert's contract, moving him into Ligier and then Benetton.

An Administration Order was made in respect of the Company on 12 September 1994, and it was compulsorily wound up by the Court on 13 February 1995. A sworn statement of affairs showed that the company had an estimated deficiency of £12,050,000. Disqualification Orders were made against Peter Collins, and Peter Wright on 15 October 1998 for nine years, and seven years respectively.

Before the end of the 1994 season, the team had been sold to David Hunt, brother of 1976 World Champion James, and Mika Salo was hired to replace Herbert for the last two races of the season. In December, however, work on the design of a new car (the Lotus 112) was halted and the staff laid off. In February 1995 Hunt announced an alliance with Pacific Grand Prix, who like Lotus were also based in Norfolk in the UK, and Team Lotus came to an end. Pacific were initially referred to as Pacific Team Lotus and their car featured a green stripe with the Lotus logo.

Pacific left Formula One after the 1995 Australian Grand Prix. The last race for Lotus was the 1994 Australian Grand Prix.

2010: return of Lotus name in Formula One

Following the 1994 collapse – but before the end of that season – the rights to the name Team Lotus were purchased by David Hunt, brother of former F1 champion James Hunt.[5] In 2009, when the FIA announced an intention to invite entries for a budget-limited championship in 2010, Litespeed acquired the right to submit an entry under the historic name.[5] Lotus Cars, the sister company of the original Team Lotus, distanced itself from the new entry and announced its willingness to take action to protect its name and reputation if necessary.[6] When the 2010 entry list was released on 12 June 2009, the Litespeed Team Lotus entry was not one of those selected.[7] In September 2009, reports emerged of plans for the Malaysian Government to back a Lotus named entry for the 2010 championship to promote the Malaysian car manufacturer Proton, which at that time owned Lotus Cars.[8] On 15 September 2009 the FIA announced that the Malaysian backed team Lotus Racing had been granted admission into the 2010 season.[9] Group Lotus later terminated the licence for future seasons as a result of what it called "flagrant and persistent breaches of the licence by the team". A little over one year later, on 24 September 2010, it was announced that Tony Fernandes (Lotus Racing) had acquired the name rights of Team Lotus from David Hunt, marking the official rebirth of Team Lotus in Formula One.[10] Then on 8 December 2010, Genii Capital and Group Lotus plc announced the creation of "Lotus Renault GP", the successor to the Renault F1 Team that would contest the 2011 FIA Formula One World Championship. The announcement came as part of a 'strategic alliance' between the two companies and at the time meant there would be two teams running as Lotus that season. Although neither had any physical links to the pre-1994 Team Lotus Formula 1 team, only Fernandes's "Team Lotus" had the name, while Lotus-Renault was backed by Group Lotus plc.

On 23 December 2010, the Chapman family released a statement in which they unequivocally backed Group Lotus in the dispute over the use of the Lotus name in Formula One, and made it clear that they would prefer that the Team Lotus name did not return to F1.[11]

On 27 May 2011, Justice Peter Smith finally made his verdict public in High Court, giving permission to Tony Fernandes to naming his F1 team Team Lotus after purchasing the rights to the name from previous owner David Hunt. Added to that, Group Lotus are entitled to race in F1 using the historic black and gold livery and have the right to use the Lotus marque on cars for road use. In summary, the 2011 Formula One season had two teams running the Lotus name with Group Lotus entitled to use the name "Lotus" on its own while Fernandes's team used "Team Lotus".[12]

In 2012, Lotus-Renault GP was given the rights to the Lotus name and was renamed Lotus F1, whereas Fernandes's team was renamed Caterham F1 following his purchase of Caterham Cars.[13] The team was active for 4 seasons, then it returned to the French constructor Renault.

Formula One results

References

- ↑ "retrieved on 1 May 2008". Gglotus.org. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ GrandPrix.com. "Ex-Lotus boss Peter Warr dies". 6 October 2010. Accessed 23 June 2011. http://www.grandprix.com/ns/ns22654.html

- ↑ "Car Model: Lotus 109". ChicaneF1.com. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ↑ "If it hadn't been for that day at Brands". forix.com. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- 1 2 "Lotus name ready for return to F1". BBC News. 7 June 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ↑ "Lotus company not behind 'Team Lotus'". Autosport.com. 10 June 2009. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- ↑ "2010 FIA Formula One World Championship Entry List". Fia.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ "Malaysians pushing for Lotus F1 entry". Autosport.com. 3 September 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ "Lotus to be 13th team on F1 grid in 2010". Fia.com. 15 September 2009. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ Archived 5 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Chapman family backs Group Lotus over Fernandes". ESPN F1. 23 December 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ "Both Lotus' claim High Court Victory". planetF1.com. 27 May 2011. Archived from the original on 30 May 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ↑ Cary, Tom (4 November 2011). "Row over Lotus name in F1 finally over as F1 Commission sanction three name changes". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2012.