Theriac or theriaca is a medical concoction originally labelled by the Greeks in the 1st century AD and widely adopted in the ancient world as far away as Persia, China and India via the trading links of the Silk Route.[2] It was an alexipharmic, or antidote for a variety of poisons and diseases. It was also considered a panacea,[3] a term for which it could be used interchangeably: in the 16th century Adam Lonicer wrote that garlic was the rustic's theriac or Heal-All.[4]

The word theriac comes from the Greek term θηριακή (thēriakē), a feminine adjective signifying "pertaining to animals",[5] from θηρίον (thērion), "wild animal, beast".[6] The ancient bestiaries included information—often fanciful—about dangerous beasts and their bites. When cane sugar was an exotic Eastern commodity, the English recommended the sugar-based treacle as an antidote against poison,[7] originally applied as a salve.[8] By extension, treacle could be applied to any healing property: in the Middle Ages the treacle (i.e. healing) well at Binsey was a place of pilgrimage.

Norman Cantor observes[9] that the remedy's supposed effect followed the homeopathic principle of "the hair of the dog", whereby a concoction containing some of the poisonous (it was thought) flesh of the serpent would be a sovereign remedy against the creature's venom: in his book on medicine,[10] Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster, wrote that "the treacle is made of poison so that it can destroy other poisons".[11] Another rationale for including snake flesh was the widespread belief that snakes contained an antidote to protect themselves against being poisoned by their own venom.[12] Thinking by analogy, Henry Grosmont also thought of theriac as a moral curative, the medicine "to make a man reject the poisonous sin which has entered into his soul". Since the plague, and notably the Black Death, was believed to have been sent by God as a punishment for sin and had its origins in pestilential serpents that poisoned the rivers, theriac was a particularly appropriate remedy or therapeutic.[13] By contrast, Christiane Fabbri argues[14] that theriac, which very frequently contained opium, actually did have palliative effect against pain and reduced coughing and diarrhea.

History

According to legends, the history of theriac begins with the king Mithridates VI of Pontus who experimented with poisons and antidotes on his prisoners. His numerous toxicity experiments eventually led him to declare that he had discovered an antidote for every venomous reptile and poisonous substance. He mixed all the effective antidotes into a single one, mithridatium or mithridate. Mithridate contained opium, myrrh, saffron, ginger, cinnamon and castor, along with some forty other ingredients.[15] When the Romans defeated him, his medical notes fell into their hands and Roman medici began to use them. Emperor Nero's physician Andromachus improved upon mithridatum by bringing the total number of ingredients to sixty-four, including viper's flesh,[15] a mashed decoction of which, first roasted then well aged, proved the most constant ingredient.[16] Lise Manniche, however, links the origins of theriac to the ancient Egyptian kyphi recipe, which was also used medicinally.[17]

Greek physician Galen devoted a whole book Theriaké to theriac. One of his patients, Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, took it on a regular basis.

In 667, ambassadors from Rûm presented the Emperor Gaozong of the Tang dynasty in China with a theriac. The Chinese observed that it contained the gall of swine, was dark red in colour and the foreigners seemed to respect it greatly. The Tang pharmacologist Su Kung noted that it had proved its usefulness against "the hundred ailments". Whether this panacea contained the traditional ingredients such as opium, myrrh and hemp, is not known.[18]

In the Middle East, theriac was known as Tiryaq, and makers of it were known as Tiryaqi.[19]

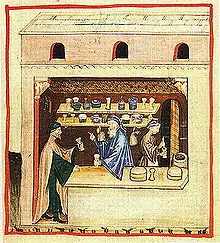

In medieval London, the preparation arrived on galleys from the Mediterranean, under the watchful eye of the Worshipful Company of Grocers. Theriac, the most expensive of medicaments, was called Venice treacle by the English apothecaries.

At the time of the Black Death in the mid 14th century, Gentile da Foligno, who died of the plague in June 1348, recommended in his plague treatise that the theriac should have been aged at least a year. Children should not ingest it, he thought, but have it rubbed on them in a salve.[20]

In 1669, the famous French apothecary, Moyse Charas, published the formula for theriac, seeking to break the monopoly held by the Venetians at that time on the medication, thereby opening up the transfer of medical information.[2]

Production

The production of a proper theriac took months with all the collection and fermentation of herbs and other ingredients. It was supposed to be left to mature for years. As a result, it was also expensive and hence available only for the rich.

According to the commentary on Exodus, Ki Tisa, the Spanish scholar Moses ben Nachman lists the ingredients of theriac as leaven, honey, flesh of wild beasts and reptiles, dried scorpion and viper.[21]

According to Galen, theriac reached its greatest potency six years after preparation and kept its virtues for 40 years. It was therefore good practice to make large batches; in 1712, 150 kg of theriac was prepared at one session in Maastricht in the Netherlands.[12]

By the time of the Renaissance, the making of theriac had become an official ceremony, especially in Italy. Pharmacists sold it as late as 1884.

Theriaca Andromachi Senioris

Theriaca andromachi or Venice Treacle contained 64 ingredients. In addition to viper flesh and opium, it included cinnamon, agarics and gum arabic. The ingredients were pulverized and reduced to an electuary with honey.

The following ingredients for the theriac were taken from the Amsterdammer Apotheek (1683) and translated from the old Latin names into the Latin names now used where possible.[22] Not all ingredients are known, and identifications and assignments below are tentative.

Roots: Iris, Balsamorhiza deltoidea, Potentilla reptans (creeping cinquefoil), Rheum rhabarbarum (garden rhubarb), Zingiber officinale, Angustifolia odorata, Gentiana, Meum athamanticum (spignel), Valeriana, Corydalis cava (hollowroot), glycyrrhiza

Stems and barks: Cinnamomum zeylanicum (cinnamon), Cinnamomum aromaticum (cassia)

Leaves: Teucrium scordium (water germander), Fraxinus excelsior, Clinopodium calamintha (lesser calamint), Marrubium vulgare (white or common horehound), Cymbopogon citratus (West-Indian lemongrass), Teucrium chamaedrys (wall germander), Cupressasae, Laurus nobilis (bay laurel), Polium montanum, Cytinus hypocistis

Flowers: Rosa, Crocus sativus, Lavandula stoechas (French lavender), Lavandula angustifolia (common or English lavender), Centaurea minoris

Fruits and seeds: Brassica napus (rapeseed), Petroselinum (parsley), Nigella sativa, Pimpinella anisum (anise), Elettaria cardamomum, Foeniculum vulgare (fennel), Hypericum perforatum (St. John's wort), seseli, thlaspi, Daucus carota (carrot), Piper nigrum (black pepper), Piper longum (long pepper), Juniperus (juniper), Syzygium aromaticum (clove), Canary Island wine, Agaricus fruiting bodies

Gums, oils and resins: Acaciae (acacia), Styrax benzoin, Gummi arabicum, Sagapeni (wax of an unknown tree, possibly some kind of Ferula), Gummi Opopanax chironium, Gummi Ferula foetida, Commiphora (myrrh), incense, Turpentine from Cyprus, oil from Myristica fragans (nutmeg), Papaver somniverum latex (opium).

Animal parts and products: Castoreum, Trochisci Viperarum, Narbonne white honey

Mineral substances: Boli armen. verae, Chalciditis (copper salts), Dead sea bitumen

See also

Notes

- ↑ Pancaroǧlu, Oya (2001). "Socializing Medicine: Illustrations of the Kitāb al-diryāq". Muqarnas. 18: 155–172. doi:10.2307/1523306. ISSN 0732-2992.

- 1 2 Boulnois, Luce (2005). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants. Hong Kong: Odyssey Books. p. 131. ISBN 962-217-721-2.

- ↑ Griffin, J. P. (2004). "Venetian treacle and the foundation of medicines regulation". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. Wiley. 58 (3): 317–25. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02147.x. PMC 1884566. PMID 15327592.

- ↑ A. Vogel, "Allium sativum". 'Plant Encyclopedia.

- ↑ θηριακή. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ θηρίον in Liddell and Scott.

- ↑ "Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary: treacle". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. "Treacle".

- ↑ Cantor 2001:174.

- ↑ Livre de seyntz medicines, 1354.

- ↑ Cantor, Norman F. (2015-03-17). In the Wake of the Plague: The Black Death and the World It Made. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-9774-8.

- 1 2 Hudson, Briony (8 October 2017). "Theriac: An ancient brand?". Wellcome Collection.

- ↑ Noted by Cantor 2001:174.

- ↑ Christiane Fabbri, 2007. Treating Medieval Plague: The Wonderful Virtues of Theriac.

- 1 2 (Hodgson 2001, p. 18)

- ↑ Norman F. Cantor, In the Wake of the Plague: The Black Death and the World It made(New York: Harper) 2001: 174ff.

- ↑ Manniche, Lise (1999). Sacred Luxuries. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3720-5.

lise manniche sacred luxuries.

- ↑ (Schafer 1985, p. 184)

- ↑ Redhouse, James William (1861). Turkish and English Lexicon (1890 ed.). Constantinople: A. H. Boyajian. p. 540. OCLC 988570649.

- ↑ Noted by Cantor 2001:175, who observes that Gentile also used gold and ground gemstones in medications and recommended amulets.

- ↑ Ramban Commentary to Exodus 30:34. See also Ritva (Pesahim 45b), Rabbenu Manoah (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Chametz u'Matzah 4:10), and Shulchan Aruch, Orah Haim 442

- ↑ Pharmacopaea Amstelredamensis, of d'Amsterdammer apotheek, in welke allerlei medicamenten, zijnde tot Amsterdam in 't gebruik, konstiglijk bereid worden: als ook des selfs krachten en manier van ingeven [Pharmacopaea Amstelredamensis, or the Amsterdammer pharmacy, in which all kinds of medications, being used in Amsterdam, are prepared in a constant manner: as well as the self's powers and method of entering]. by Jan ten Hoorn (bookseller, over 't oude Heere Logement). 1683.

References

- Hodgson, Barbara (2001), In the Arms of Morpheus: The Tragic History of Morphine, Laudanum and Patent Medicines, Firefly Books, ISBN 1-55297-540-1.

- Majno, Guido (1991), The Healing Hand: Man and Wound in the Ancient World, Harvard University Press, pp. 413–417, ISBN 0-674-38331-1.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1985), The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T'Ang Exotics, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-05462-8.

Further reading

- Griffin, J. P. (2004). "Venetian treacle and the foundation of medicines regulation". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 58 (3): 317–325. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02147.x. PMC 1884566. PMID 15327592.

- Raj D, Pękacka-Falkowska K, Włodarczyk M, Węglorz J. The real Theriac - panacea, poisonous drug or quackery? J Ethnopharmacol. 2021 Dec 5;281:114535. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114535. Epub 2021 Aug 17. PMID: 34416297.