| Third Transjordan attack | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

The Third Transjordan attack by Chaytor's Force, part of the British Empire's Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF), took place between 21 and 25 September 1918, against the Ottoman Empire's Fourth Army and other Yildirim Army Group units. These operations took place during the Battle of Nablus, part of the Battle of Megiddo which began on 19 September in the final months of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of World War I. Fought on the right flank and subsidiary to the Battle of Nablus, the Third Transjordan attack began northwards, with the assault on Kh Fasail. The following day a section of Chaytor's Force, attacked and captured the Ottoman Empire's 53rd Division (Seventh Army) on the main eastwards line of retreat out of the Judean Hills across the Jordan River. Retreating columns of the Yildirim Army Group were attacked during the battle for the Jisr ed Damieh bridge, and several fords to the south were also captured, closing this line of retreat. Leaving detachments to hold the captured bridge and fords, Chaytor's Force began their eastwards advance by attacking and capturing the Fourth Army garrison at Shunet Nimrin on their way to capture Es Salt for a third time. With the Fourth Army's VIII Corps in retreat, Chaytor's Force continued their advance to attack and capture Amman on 25 September during the Second Battle of Amman. Several days later, to the south of Amman, the Fourth Army's II Corps which had garrisoned the southern Hejaz Railway, surrendered to Chaytor's Force at Ziza, effectively ending military operations in the area.

The British Empire victories during the Third Transjordan attack resulted in the occupation of many miles of Ottoman territory and the capture of the equivalent of one Ottoman corps. Meanwhile, the remnants of the Fourth Army were forced to retreat in disarray north to Damascus, along with the remnants of the Seventh and Eighth Armies after the EEF victories during the Battle of Sharon and Battle of Nablus. Fighting extended from the Mediterranean Sea during these seven days of battle, resulting in the capture of many thousands of prisoners, and extensive territory. After several days pursuing remnant columns, Desert Mounted Corps captured Damascus on 1 October. The surviving remnants of Yildirim Army Group which escaped Damascus were pursued north during the Pursuit to Haritan when Homs was occupied and Aleppo was captured by Prince Feisal's Sherifial Army Force. Soon after, on 30 October, the Armistice of Mudros was signed between the Allies and the Ottoman Empire, ending the Sinai and Palestine campaign.

Background

Following the victory at the Battle of Jerusalem at the end of 1917, and the Capture of Jericho in February 1918, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) crossed the Jordan River, establishing bridgeheads in March prior to the First Transjordan attack on Amman. These bridgeheads remained after the Second Transjordan attacks on Shunet Nimrin and Es Salt when a second withdrawal back to the Jordan Valley took place from 3 to 5 May. This marked the end of major operations in the area until September 1918.[1] General Edmund Allenby, the commander of the EEF, decided to occupy the Jordan Valley during the summer of 1918 for a number of reasons. A retreat out of the valley would further enhance the morale of the German and Ottoman forces, and their standing among the peoples living in the region, following their two Transjordan victories.[2] So important did Allenby consider the support of the Hedjaz Arabs to the defence of his right flank, that they were substantially subsidised:

I think we shall manage the subsidy required as well as the extra £50,000 you require for Northern Operations ... I am urging for another £500,000 additional to the £400,000 en route from Australia and I am sure you will do what you can, through the WO to represent the importance of not risking a delay again in the payment of our Arab subsidy.

The road from the Hedjaz railway station at Amman to Shunet Nimrin remained a serious threat to the occupation of the Jordan Valley, as a large German and Ottoman force could quickly be moved along this line of communication from Amman to Shunet Nimrin, from where they could mount a major attack into the Jordan Valley.[2][Note 1] As Allenby explains,

I am not strong enough to make holding attacks on both flanks, and the Turks can transfer their reserves from flank to flank as required. The Turks have more of these, the VII Army have 2400, and the VIII Army 5800 in Reserve. I must maintain my hold on the bridges of the Jordan, and my control of the Dead Sea. This will cause the Turks to keep a considerable force watching me, and ease pressure on Feisal and his forces. It is absolutely essential to me that he should continue to be active. He is a sensible, well–informed man; and he is fully alive to the limitations imposed on me. I keep in close touch with him, through Lawrence. I have now in the valley two Mounted Divisions and an Indian Infantry Brigade. I cannot lessen this number yet.

— Allenby letter to Wilson 5 June 1918[4]

By July, Allenby was "very anxious to make a move in September," when he aimed to capture Tulkarm, Nablus and the Jisr ed Damieh bridge across the Jordan River. He stated, "The possession by the Turks of the road Nablus–Jisr ed Damie–Es Salt is of great advantage to them; and, until I get it, I can't occupy Es Salt with my troops or the Arabs." He hoped the capture of this important Ottoman line of communication from Nablus along the Wadi Fara to the Jordan River at Jisr ed Damieh and on to Es Salt would also "encourage both my own new Indian troops and my Arab Allies."[5]

EEF front line

From the departure of the Australian Mounted Division in August steps were taken to make it appear the valley was still fully garrisoned.[6][7] On 11 September the 10th Cavalry Brigade, which included the Scinde Horse, left the Jordan Valley. They marched via Jericho, 19 miles (31 km) to Talaat de Dumm, then a further 20 miles (32 km) to Enab, reaching Ramleh on 17 September in preparation for the beginning of the Battle of Megiddo.[8]

Chaytor's Force held the right flank from their junction with the XX Corps in the Judean Hills 8 miles (13 km) north west of Jericho, across the Jordan Valley, and then southwards through the Ghoraniye and Auja bridgeheads to the Dead Sea.[9] This area was overlooked by well sited Ottoman or German long range guns and an observation post on El Haud.[10][11]

Ottoman front line

The Ottoman front line had been strengthened after the Second Transjordan attack. It began in the south, where Ottoman cavalry guarded tracks to Madaba before continuing with strongly wired entrenchments. In front of these, advanced posts extended from the foothills opposite the ford across the Jordan River at Makhadet Hijla to about 4 miles (6.4 km) north of the Jericho to Es Salt road. The road had been cut at the Ghorianyeh Bridge before the First Transjordan attack, in the vicinity of Shunet Nimrin. The front line was strengthened by advanced posts which were also wired on the left flank at Qabr Said, Kh. el Kufrein and Qabr Mujahid. From their right flank in the foothills a wired line of redoubts and trenches facing south ran from 8,000 yards (7,300 m) north of Shunet Nimrin, across the Jordan Valley to the Jordan River, 1,000 yards (910 m) south of the Umm esh Shert ford.[12][13][14] This line was continued west of the river by a series of individual "wired-in redoubts with good fields of fire,"[15] then as a series of trenches and redoubts along the northern or left bank of the Wadi Mellaha. These were followed by a "series of trenches and redoubts towards Bakr Ridge which were entrenched but not wired. A strong advanced position of well built sangars and [sic] [which were] wired in was held at Baghalat."[13] Bakr Ridge in the Judean Hills was situated to the west of the salient at El Musallabe which was held by the EEF. The Ottoman front line was supported by entrenched positions on Red Hill beside the Jordan River, which was also the site of their main artillery observation point.[12][13][14]

Battle of Megiddo 19 to 20 September

During the first 36 hours of the Battle of Megiddo, between 04:30 on 19 September and 17:00 on 20 September, the German and Ottoman front line had been cut by infantry of the EEF's XXI Corps. This allowed the cavalry of the Desert Mounted Corps to pass through the gap and begin their ride towards their objectives at Afulah, Nazareth, and Beisan. The two Ottoman armies were left without effective communications, and so could not organize any combined action against the continuing onslaught by the British Empire infantry in the Judean Hills. The Ottoman Seventh and Eighth Armies were forced to withdraw northwards along the main roads and railways from Tulkarm and Nablus, which converged to run through the Dothan Pass to Jenin on the Esdrealon Plain. There, retreating columns from these two Ottoman armies would be captured during the evening of 20 September by the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, who already occupied the town.[16][17][18][Note 2]

Liman von Sanders escapes

Otto Liman von Sanders, the commander of the Yildirim Army Group, was forced out of his headquarters at Nazareth during the Battle of Nazareth on the morning of 20 September by elements of the 5th Cavalry Division. He drove via Tiberias and Samakh where he alerted the garrisons, to arrive at Deraa on the morning of 21 September, on his way to Damascus. At Deraa, Liman von Sanders received a report from the Fourth Army, which he ordered to withdraw to the Deraa to Irbid line without waiting for the troops which garrisoned the southern Hejaz.[19][20][21][Note 3]

Prelude

Chaytor's Force

While the Battles of Sharon and Nablus were taking place, it was necessary to deploy a strong force, to defend the right flank of the Desert Mounted Corps, the XXI and the XX Corps fighting from the Mediterranean coast and into the Judean Hills. Their right flank in Jordan Valley was protected by Chaytor's Force from the threat of a flanking attack by the Ottoman Fourth Army.[22][23] This composite force commanded by Major General Edward Chaytor[24] has been described by Bou as "nearly equivalent to two divisions,"[25] being a reinforced mounted infantry division of 11,000 men.[26] By the end of operations on 30 September Chaytor's Force consisted of "8,000 British, 3,000 Indian, 500 Egyptian Camel Transport Corps troops."[27]

Medical support

In addition to the Anzac Mounted Division's medical units, the 1/1st Welsh and the 157th Indian Field Ambulances, the Anzac Field Laboratory, and a new operating unit formed from personnel of the 14th Australian General and the 2nd Stationary Hospitals, were attached to Chaytor's Force.[28]

A receiving station was formed from the immobile sections of light horse and mounted rifle brigades' field ambulances, a section from the 1/1st Welsh and the 157th Indian Field Ambulances with an operating unit, the Anzac Field Laboratory, and a detachment from an Egyptian hospital. This Receiving Station took over the site near Jericho, occupied by the main dressing station during the two Transjordan attacks, which could accommodate 200 patients in mud huts, 400 patients in tents, and 700 patients in the abandoned Desert Mounted Corps headquarters.[28]

Air support

The Royal Air Force's (RAF)'s 5th (Corps) Wing, headquartered at Ramle, deployed one flight of the No. 142 Squadron RAF on 18 September to Chaytor's Force. The flight was based at Jerusalem, with responsibility for cooperation with artillery, contact patrols, and tactical reconnaissance up to 10,000 yards (9,100 m) in advance of Chaytor's Force.[29]

No. 1 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps (AFC), operating Bristol Fighters, was to carry out bombing and strategic reconnaissance missions, provide a general oversight of the whole Megiddo battlefield, and report all developments. Meanwhile, Nos. 111 and 145 Squadrons, which were equipped with S.E.5.a aircraft, were to constantly patrol over Jenin aerodrome throughout the day to bomb and machine gun all targets in the area, and prevent any aircraft from taking off. Airco DH.9 aircraft from No. 144 Squadron were to bomb the Afulah telephone exchange and railway station, the Messudieh Junction railway lines, and the Ottoman Seventh Army headquarters and telephone exchange at Nablus. The newly arrived Handley Page bomber, armed with 16 112-pound (51 kg) bombs and piloted by the Australian Ross Smith, was to support No. 144 Squadron's bombing of Afulah.[30][31][32][Note 4]

Jordan Valley deployments

Chaytor took command of the Jordan Valley garrison on 5 September 1918. The right sector, under the command of Brigadier General Granville Ryrie, was held by the 2nd Light Horse Brigade and the 20th Indian Brigade. The left sector, under the command of Brigadier-General W. Meldrum, was held by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, the 38th Battalion Royal Fusiliers, and the 1st and 2nd Battalions British West Indies Regiment, supported by a field artillery battery and an Indian mountain battery. The 39th Battalion Royal Fusiliers formed the sector reserve, while the 1st Light Horse Brigade was in force reserve.[33][34]

While the Ottoman Fourth Army continued to hold the eastern side of the Jordan Valley, Es Salt, Amman and the Hejaz railway, Chaytor's smaller force was to continue the EEF's occupation of the Jordan Valley. As soon as possible, Chaytor's Force was to advance northwards to capture the Jisr ed Damieh bridge, which would cut a main line of retreat for the Ottoman Seventh and Eighth Armies. This was also a main line of communication between the two armies west of the Jordan River in the Judean Hills with the Fourth Army in the east.[23][35][36][37] The expectation was that, the attacks on the Eighth Army by the XXI and Desert Mounted Corps, and the start of the Battle of Nablus attacks on the Seventh Army, would force the Fourth Army to withdraw northwards along the Hejaz railway to conform with the withdrawals of the Seventh and Eighth Armies.[9]

Preliminary operations

Lieutenant General Harry Chauvel, the Australian commander of Desert Mounted Corps, instructed Chaytor to hold his ground "for the present," but to closely watch the Ottoman forces during around-the-clock patrolling, and to immediately occupy any abandoned enemy positions.[28][38] From 16 September, the Ottoman front line was closely monitored, while the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade and the British West Indies Regiment's infantry battalions carried out demonstrations to the north on the western side of the Jordan River. Chaytors Force was prepared to exploit all withdrawals by the Fourth Ottoman Army, including a third Occupation of Es Salt and a Second Battle of Amman.[12][38][39]

In addition to the close patrol work, demonstrations against Ottoman defences were made during the nights of 17 and 18 September, by the 1st Light Horse Brigade and a regiment of 2nd Light Horse Brigade, which rode out from the bridgeheads in the Jordan Valley. The Ottoman "heavy high-velocity gun" retaliated, firing shells on Jericho, and to the north of town on Chaytor's headquarters in the Wadi Nueiame.[13][40]

Yildirim Army Group

The Yildirim Army Group commanded by von Sanders consisted of 40,598 front line infantrymen armed with 19,819 rifles, 273 light machine guns and 696 heavy machine guns in August 1918.[Note 5] The high number of machine guns reflected the Ottoman Army's new tables of organization and the machine gun component of the German Asia Corps. The infantry were organised into 12 divisions and deployed along the 90 kilometres (56 mi) of front line from the Mediterranean to the Dead Sea: the Eighth Army from the coast into the Judean Hills, the Seventh Army in the Judean Hills and towards the Jordan, with the Fourth Army east of the Jordan River.[41]

An operational reserve was formed from the 2nd Caucasian Cavalry Division in the Eighth Army area and the 3rd Cavalry Division in the Fourth Army area.[42]

Fourth Army

The Ottoman Fourth Army consisting of 6,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry supported by 74 guns was commanded by General Mohammed Jemal Pasha.[Note 6] The army was headquartered at Amman.[Note 7] This army was composed of the VIII Corps' 48th Infantry Division, the Composite Division of a German battalion group,[Note 8] the Caucasus Cavalry Brigade, the division-sized Serstal Group, the 24th and 62nd Infantry Divisions, with the 3rd Cavalry Division in reserve. There were 6,000 Ottoman soldiers with 30 guns in the II Corps, known as the Seria Group or Jordan Group, which garrisoned the Hejaz railway along the line from Ma'an southwards towards Mecca.[42][43][44][45]

- Deployment

The Seventh and Fourth Armies touched at Baghalat, 6 miles (9.7 km) west north west of Umm esh Shert. Both sides of the Jordan River were defended by the 24th Infantry Division and the 3rd Cavalry Division, and both sides of the Ghoraniyeh to Es Salt Road were held by the VIII Corps's 48th Division. The Composite Division was on their left, while the Caucasus Cavalry Brigade and the Mule-Mounted Infantry Regiment held outposts extending southwards towards the Dead Sea. The II Corps was responsible for some 200 miles (320 km) of the Hejaz Railway, a strong detachment of about seven battalions was at Ma'an and about eight battalions were deployed between Ma'an and Amman. The Fourth Army's reserve was formed by the German 146th Regiment, the 3rd Cavalry Division and part of the 12th Regiment at Es Salt.[14]

The Fourth Army strongly garrisoned Shunet Nimrin, the entrenched area in the foothills which had repulsed an attack by Chetwode on 18 April and a second attack at the end of April during the Second Transjordan attack. The Fourth Army also held substantial forces at Amman, and guarding tunnels and viaducts along the Hejaz railway near Amman.[46]

Battle of Nablus eastern flank 19 to 21 September

Chaytor's Force continued to vigorously patrol the eastern flank as the Battles of Sharon and Nablus developed. They were opposed on the western side of the Jordan River by the Ottoman 53rd Division (Seventh Army) to the west of Baghalat and units of the Fourth Army, which held the Ottoman front line to east of Baghalat. The Auckland Mounted Rifle and Wellington Mounted Rifle Regiments carried out patrols north from the Wadi Aujah and west of Baghalat before dawn on 19 September, but were "compelled to withdraw" due to heavy artillery and machine gun fire. Progress made by the 160th Brigade (53rd Division, XX Corps),[Note 9] in the Judean Hills enabled one of its mountain batteries to direct fire at the Ottoman front line position on the Bakr Ridge during the afternoon. Three companies of the 2nd Battalion British West Indies Regiment, (Chaytor's Force) supported by the 160th Brigade's battery, "drove in" Ottoman outposts and captured a ridge to the south of Bakr Ridge at 15:25, despite intense enemy artillery and machine gun fire. Although heavily shelled, they dug in and held their position.[33][47][48] The British West Indies Regiment advances towards Bakr Ridge were consolidated, and continued at dawn on 20 September, when their 2nd Battalion captured Bakr Ridge. An attack by the 38th Battalion Royal Fusiliers (Chaytor's Force) at Mellaha opposed by machine gun and rifle fire, was less successful. An advance by the 1st and 2nd Battalions, British West Indies Regiment had by 7:00 captured Grant Ridge, Baghalat and Chalk Ridge. A large Ottoman force was seen south of Kh. Fusail in the late morning on the western side of the Jordan River. By 19:00 the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade had begun its advance towards Tel sh edh Dhib. Jericho was shelled again in the mid-afternoon.[40][47][48]

The 2nd Light Horse Brigade and Patiala Infantry, (Chaytor's Force) advanced on 20 September eastwards across the Jordan Valley toward the strongly entrenched Shunet Nimrin position, and Derbasi on the Ottoman left flank. The 6th Light Horse and 7th Light Horse Regiments, with a company of Patiala Infantry, were shelled by guns from El Haud in the foothills of Moab as they moved across the valley. Positions east of the Jordan River, including Mellaha, continued to be strongly held by Fourth Army units.[40][47]

Aircraft reconnaissance, during a second dawn patrol on 20 September reported the whole area quiet, from Jisr ed Damieh bridge north to Beisan and from the bridge east across the Jordan Valley to Es Salt. Bristol Fighters attacked 200 vehicles at the Wadi Fara elbow, seen withdrawing from Nablus towards Khurbet Ferweh.[49] The last aerial reconnaissance of the day reported seeing a brigade of Desert Mounted Corps' cavalry entering Beisan on the Esdrealon Plain. They also reported that three large fires were burning at Nablus railway station, while fires were also reported at the Balata dumps, and the whole Ottoman line from El Lubban to the Jordan appeared to be "alarmed", according to Cutlack.[50]

Only the Fourth Army remained intact by 21 September after the successful attacks during the Battle of Sharon and the Battle of Nablus. Allenby's next priority became the destruction of the Fourth Army, which had begun to move to conform with the withdrawals of the Seventh and Eighth Armies. Chaytor's Force was to advance eastwards to capture Es Salt and Amman, and to intercept and capture the 4,600-strong southern Hejaz garrison.[23][35][36][37] During the first days of the Battle of Megiddo, the Fourth Army had remained in position, while Chaytor's Force carried out demonstrations against it.[51]

Asia Corps retreat

Liman von Sanders had been out of contact with his three armies until he reached Samakh on the afternoon of 20 September. As soon as he was able, he placed the 16th and 19th Infantry Divisions of the Asia Corps (Eighth Army) under his direct orders. These two divisions made contact with Asia Corps commander von Oppen to the west of Nablus during the morning of 21 September, when Asia Corps was being reorganised; remnants of the 702nd and 703rd Battalions (Asia Corps) were amalgamated into one battalion, while the 701st Battalion remained intact.[52] At 10:00 that morning, von Oppen was informed that the EEF was approaching Nablus and that the Wadi Fara road was blocked. He attempted to retreat down to the Jordan at the Jisr ed Damieh bridge via Beit Dejan, 7 miles (11 km) east south east of Nablus, but found this way blocked by Chaytor's Force. He then ordered a retreat via Mount Ebal, leaving behind all guns and baggage. Asia Corps bivouacked at Tammun with the 16th and 19th Divisions at Tubas on the evening of 21 September, unaware that Desert Mounted Corps had already occupied Beisan.[53]

Capture of Kh Fasail on 21 September

The Seventh and Fourth Armies had begun to withdraw, and before dawn on 21 September Chaytor ordered the Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment to advance and capture Kh Fasail, 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Baghalat on the road to the Jisr ed Damieh bridge. The regiment, supported by one section of their brigade's machine gun squadron and two guns from 29th Indian Mountain Battery, advanced along an old Roman road on the western bank of the Jordan River, with patrols pushed towards Jisr ed Damieh and Umm esh Shert. They captured Kh Fusail and Tel es edh Dhiab, along with 26 prisoners and two machine guns. Shortly afterwards the regiment discovered an Ottoman defensive line stretching from the ford at Mafid Jozele on the Jordan River to El Musetterah 3.5 miles (5.6 km) to the north west, defending the Jisr ed Damieh bridge. Units of the Seventh Army were seen withdrawing along the Wadi el Fara road from Nablus towards the Jisr ed Damieh bridge. This Ottoman defensive line was reported at 08:05 to be strongly held, but movement in the rear was detected and at 16:15 the Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment reported they were withdrawing from Mafid Jozele.[48][54][55][56]

Meldrum's Force, commanded by Brigadier-General W. Meldrum, was formed at 20:30 from the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade and their machine gun squadron, mounted sections of the 1st and 2nd Battalions British West Indies Regiment, the 29th Indian Mountain Battery, and the Ayrshire (or Inverness) Battery RHA. This force concentrated half an hour later east of Musallabeh, to begin their advance to Kh. Fusail where they arrived just before midnight. At the same time, the Commander Royal Artillery (CRA) pushed guns forward into Mellaha to attack Ottoman guns on Red Hill on the eastern bank of the Jordan River, while the 1st Light Horse Brigade took over the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade position at Madbeh.[48][54][55]

Kh. Fusail was about half way to the Jisr ed Damieh bridge, and after waiting for the dismounted sections of Meldrum's Force to arrive, the consolidated force advanced to attack Jisr ed Damieh. The 2nd Battalion, British West Indies Regiment remained to garrison Kh. Fusail, occupying a position at Talat Armah to protect Meldrum's right flank and rear, and if necessary to block the track from Mafid Jozele.[48][56][57] Aerial reconnaissance flights during the evening of 21 September, confirmed that Shunet Nimrin in the rear of Meldrum's Force was still strongly garrisoned, and that the roads and tracks running west from Amman were carrying normal traffic.[58]

Battle for Jordan River crossings 22 September

Jisr ed Damieh

Chaytor ordered Meldrum to cut the Wadi el Fara road from Nablus to Es Salt west of the Jordan River, occupy the headquarters of the Ottoman 53rd Division at El Makhruk, and capture the Jisr ed Damieh on the Wadi el Fara road over the Jordan River.[48] Meldrum's Force left Kh Fusail at midnight on 22 September with the Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment as vanguard, followed by the 1st Battalion British West Indies Regiment, which dumped their kits and blankets to move "at once" towards the bridge.[48][54][59]

The Auckland and Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiments advanced north along a Roman road, across a narrow plain between the Judean Hills to the west, but exposed to artillery fire on the eastern side across the Jordan River.[54][60] The Auckland Mounted Rifle Regiment's objective was to capture the Damieh crossing from the north east, while the Wellington Mounted Rifle Regiment's objectives were to make a frontal attack on El Makhruk, capture the headquarters of the Ottoman 53rd Division, and cut the Nablus road.[54][60]

The Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment, with one section of machine gun squadron attached, reached the Nablus to Jisr ed Damieh road early on the morning of 22 September and captured their objectives.[55][57][61][Note 10] Meanwhile the Auckland and Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiments, supported by the 1st Battalion, British West Indies Regiment, advanced to attack the Ottoman garrison holding Jisr ed Damieh. After a "hot fight" by the infantry and mounted riflemen, they forced the defenders to withdraw in disorder, and the bridge was captured intact.[57][62]

Umm esh Shert and Mafid Jozele fords

To the south of Jisr ed Damieh, the Umm esh Shert ford was captured by the 38th Battalion Royal Fusiliers (Chaytor's Force). At 03:00 on 22 September they took advantage of the absence of Ottoman defenders at Mellaha, to advance to occupy trenches overlooking the ford at Umm esh Shert, which was captured shortly afterwards.[54][63]

The Mafid Jozel ford was captured by the 2nd Battalion British West Indies Regiment, reinforced by the 3rd Light Horse Regiment, 1st Light Horse Brigade. Despite encountering strong resistance at Mellahet umm Afein, this force attacked and "drove in" the rearguard defending the ford and an Ottoman column withdrawing across the ford. Mafid Jozele was captured by 05:50 on 23 September, along with 37 prisoners, but the bridge had been destroyed at the ford.[64][65] The last remaining Ottoman defences on the western bank of the Jordan south of the Jisr ed Damieh bridge had thus been captured, although most of the Ottoman defenders of these two fords managed to escape.[63] Captures included 105 prisoners, 4 machine guns, 4 automatic rifles, transport, horses and stores.[64]

Air support on 22 September

No. 1 Squadron (AFC) patrols found the Shunet Nimrin garrison still in place on the morning of 22 September, but Rujm el Oshir camp (to the east of Jericho, half way between the Jordan River and the Hedjaz railway) had been broken up, and fires burned west of the Amman railway station. Ain es Sir camp (south east of Es Salt, half way between the Jordan River and Amman) was found to be full of Ottoman troops, but at about midday the Ottoman garrison at Es Salt was hastily packing. Australian airmen reported the whole area east of the Jordan to be on the move towards Amman by between 15:00 and 18:00, when two Bristol Fighters bombed a mass of traffic at Suweile, half-way between Es Salt and Amman, and fired nearly 1,000 machine-gun rounds.[58]

Asia Corps withdrawal continues

Von Oppen's battalions and about 700 German and 1,300 Ottoman soldiers in the 16th and 19th Infantry Divisions were moving north towards Beisan on 22 September when they learned it had already been captured. He planned to continue his withdrawal north to Samakh during the night of 22 September, where he correctly guessed that Liman von Sanders would order a strong rearguard action. However, Jevad, the commander of the Eighth Army which included Asia Corps, ordered von Oppen to move eastwards across the Jordan River. Von Oppen got all the German and some of his Ottoman soldiers across the Jordan River before the 11th Cavalry Brigade attacked and closed that line of retreat during fighting to close the Jordan River gaps. All those who had not crossed the river were captured.[66][Note 11]

Fourth Army withdrawal

While at Deraa on 21 September during his withdrawal from Nazareth to Damascus, Liman von Sanders ordered the Fourth Army to withdraw. They were to move without waiting for the II Corps/Southern Force, which had also begun to withdraw north from Ma'an and the southern Hejaz railway. The army was in general moving northwards from Amman along the railway towards Deraa by 22 September, where they were ordered to form a rearguard line from Deraa to Irbid.[19][21][67][68] Aerial reconnaissance aircraft spotted the Ottoman army withdrawal from Amman towards Deraa. Ottoman units in the hills to the south west, and a column of all arms, were seen moving from the Es Salt area towards Amman. The aircraft bombed and machine gunned this column, then flew back to report at Ramleh.[69]

Advance to Es Salt 23 September

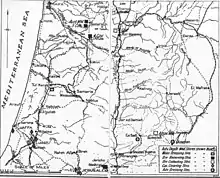

Chaytor's Force issued orders at midnight for attacks on Shunet Nimrin, Kabr Mujahid and Tel er Ramr when the retreat of the Fourth Army became apparent at 23:35 on 22/23 September. These attacks were to be carried out by the 2nd Light Horse Brigade and the mobile sections of the 20th Indian Brigade, armed with 1,500 rifles and supported by three sections of machine guns and 40 Lewis guns. This force moved eastwards along the main road from Jericho, across the Jordan River at Ghoranyeh to Es Salt towards Shunet Nimrin, while the immobile section remained in defence in the right sector of the occupied Jordan Valley. The CRA was to support this advance by targeting Shunet Nimrin.[64][70] Before Haifa on the Mediterranean coast, was captured by the 14th Cavalry Brigade during the Battle of Sharon, Chaytor's Force had crossed the Jordan River on 23 September to climb to the Plateau of Moab and Gilead on their way to capture Es Salt that evening. (See Gullett's Map 35.)[46][67]

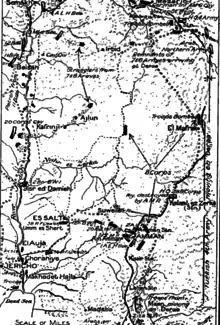

Chaytor's Force entered the hills of Moab on a front stretching from north to south of almost 15 miles (24 km). The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, the northernmost, left one squadron and the 1st Battalion British West Indies Regiment to hold the Jisr ed Damieh bridge. The brigade then advanced south east along the road from the bridge 8 miles (13 km) across the Jordan Valley to the foothills of Moab, with patrols to the east and north, to make the 3,000 feet (910 m) climb to Es Salt. The 1st Light Horse Brigade in the centre, advanced across the Jordan River at the Umm esh Shert ford at 09:10. They met no opposition as they rode up the Arseniyet track (also known as the Wadi Abu Turra track) to arrive at Es Salt at midnight. To the south, the 2nd Light Horse Brigade moved round the southern flank of the Shunet Nimrin position, captured Kabr Muahid at 04:45, before climbing to Es Salt via the village of Ain es Sir. All wheeled transport vehicles moved along the Shunet Nimrin road to Es Salt.[46][64][67][71][Note 12]

Chaytor's Anzac Mounted Division headquarters moved at 14:25 to the Ghoraniyeh crossing of the Jordan River on the main road to Es Salt from Jericho. By 18:15 in the evening, the 20th Indian Brigade had reached Shunet Nimrin with a squadron of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade as advance guard. Here they found the 150-mm long-range naval gun "Jericho Jane", also known as "Nimrin Nellie", abandoned on its side in a gully beside the road.[64][72][73][74] Patterson's Column, which had been formed at 15:00 on 22 September by the 38th and 39th Battalions Royal Fusiliers (Chaytor's Force) under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Patterson, concentrated at the Auja bridgehead just across the Jordan River to the north of Ghoraniyeh, ready to follow the 20th Indian Brigade to Shunet Nimrin.[64][71]

Capture of Es Salt

The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade' advanced guard was opposed by a line of outposts and a strongly wired Ottoman redoubt located across the main Jisr ed Damieh to Es Salt road 1 mile (1.6 km) west of Es Salt. This extensive rearguard position was attacked and outflanked by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade advanced guard consisting of the Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiment. The Ottoman redoubt had been defended by nine officers and 150 other ranks armed with rifles and machine guns. All defenders were captured, and at 16:20 on 23 September, Es Salt was occupied by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade. After establishing outpost lines and searching for prisoners and intelligence, the brigade bivouacked at Suweileh for the night, to the east of Ain Hummar on the north western road to Amman. Total captures for the day were 538 prisoners, four machine guns, two automatic rifles, two 4.2-inch howitzers, one 77-mm gun, and supplies of stores and ammunition. The brigade was reinforced by the 1st Light Horse Brigade, which reached Es Salt at 24:00, while Patterson's Column, less the 38th Royal Fusiliers, moved towards Shunet Nimrin.[48][64][73][75]

This was the third time Es Salt had been captured by the EEF in six months. The 3rd Light Horse Regiment (1st Light Horse Brigade) had captured Es Salt on 25 March, and the 8th Light Horse Regiment (3rd Light Horse Brigade) had captured Es Salt on 30 April.[64][72][73]

Air support on 23 September

At dawn on 23 September, aircraft "observed a column of fairly orderly traffic of all arms streaming down the road from Es Salt to Amman," which was subsequently bombed and machine gunned. Groups of retreating Ottoman soldiers were seen moving from the hills to the south-west towards Amman. Bombing formations attacked these columns with 48 bombs and 7,000 machine gun rounds shortly after 07:00. Eight direct hits on lorries and wagons blocked the road, and the retreat became a disorderly rout.[76] At about the same time, airmen reported that camps at Samakh and Deraa were burning and long trains "with steam up [were] facing east" and north, but "would never arrive anywhere" because the railway lines were cut. Retreating German and Ottoman forces from Nablus were seen approaching Deraa. "And this was the refuge towards which the Fourth Army from Amman was making in headlong retreat!"[76]

Consolidation of Chaytor's Force at Es Salt

During the night of 23/24 September, Allenby's General Headquarters (GHQ) instructed Chaytor's Force to continue harassment of the Fourth Army, cut off their retreat north from Amman, gain touch with the Arab Army, and maintain the detachment guarding the Jisr ed Damieh bridge.[64][72]

The main road from Jericho to Es Salt, along which all wheeled transport and supplies for Chaytor's Force travelled, had been severely damaged by the retreating Fourth Army. The 20th Indian Brigade, which had been marching up this road, was ordered to provide working parties to unblock it. This was completed by 08:50 on 24 September, when the 20th Indian Brigade continued their march to Es Salt, where they took over garrison duties from the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade.[72][77]

The 2nd Light Horse Brigade continued their advance to Es Salt up the Wadi Jeria and Wadi Sir, reaching Ain es Sir at 10:30, with forward patrols to the cross roads and north east of the village. During this advance the brigade was fired on by two Ottoman 77 mm guns located near Sueifiye. These guns fired 16 shells, then withdrew as the light horse patrols approached. The brigade bivouacked for the night on the road from Ain es Sir to Ain Hummar when a strong picquet line was maintained throughout the night. (See Falls Sketch Map 24 Amman detail) Most of the land to the west of Amman was cleared of enemy forces during the afternoon of 24 September, and by that evening Chaytor's Force, less the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, the 38th Royal Fusiliers at Shunet Nimrin and the Jisr ed Damieh detachment, was concentrated at Es Salt with mounted troops at Suweileh.[75][78][79][80]

Raid on Hejaz railway

Four officers and 100 men from the Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment carried out a successful raid from Suweileh on the Hejaz railway line north of Amman during the night of 24/25 September. This force, carrying nothing but tools and weapons, advanced 12 miles (19 km) to the railway, where they destroyed part of the Hejaz railway line 5 miles (8.0 km) north of Amman near Kalaat ez Zerka station. They "returned next morning without the loss of a man" to rejoin their regiment eleven hours and 20 miles (32 km) later.[78][81][82][Note 13]

Allenby's assessment of the battle

The Turks East of Jordan are retreating North; and I am sending all available troops from the Jordan Valley after them, via Es Salt. I've been going round hospitals today. All the sick and wounded are very cheerful and content. I've told them that they've done the biggest thing in the war – having totally destroyed two Armies in 36 hours! The VII and VIII Armies, now non–existent, were the best troops in the Turkish Empire; and were strongly backed by Germans and Austrians ... I have just heard that my cavalry have taken Haifa and Acre, today. They had a bit of a fight, at Haifa; but I have no details yet. I think my Jordan troops will probably reach Es Salt tomorrow; but they won't catch many Turks there. However, my aeroplanes have been pulverising the retreating Turks in that locality.

— Allenby, letter to Lady Allenby 23 September 1918[83]

Battle of Amman 25 September

Amman was an important city on the Ottoman lines of communication. All of the supplies and reinforcements for the Ottoman army force defending the line on the eastern edge of the Jordan Valley had passed through it. Now the city was on the main line of retreat.[84][85]

The defences at Amman had been greatly strengthened since the First Transjordan attack on Amman, with the construction of a series of redoubts that were defended by machine guns. However, the boggy ground which had limited movement during the first attack in March, was by the early autumn, firm and now favoured a rapid mounted attack.[86][Note 14]

Orders were issued for the New Zealand Mounted Rifles and the 2nd Light Horse Brigades to advance at 06:00 on 25 September to capture Amman followed by the 1st Light Horse Brigade who left at 06:30. They were to strongly assault the defenders, if the town was lightly held. If Amman was found to be held in strength the assault on the town was to be deferred until infantry could reinforce the mounted infantry. Only the outlying or forward trenches were to be attacked, artillery was to fire on the town, all lines of retreat northwards were to be cut. Aerial bombing of Amman was requested. The 1st Battalion British West Indies Regiment arrived at Suweileh at 07:00 to take over garrison duties from the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade.[78]

Within two hours the light horse and mounted rifle brigades were in sight of Amman and the attack had begun. The movement of Ottoman units were seen behind Amman, on Hill 3039. Two batteries of small guns and a number of machine guns opened fire. Several Ottoman posts 4 miles (6.4 km) from Amman were attacked and captured by the 2nd Light Horse Brigade along with 106 prisoners and four machine guns.[78][81][85][87] One regiment of the 1st Light Horse Brigade was sent at 10:00 to reinforce the left flank of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade and came under Meldrum's command. The Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment advanced half an hour later, on the right of the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment, with the 2nd Light Horse Brigade on their left. They eventually forced the Ottoman front line defenders to retire back to the main line of defence, which was also strongly supported by machine guns.[78][81][88] At noon the Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiment advanced towards "the main entrance to Amman," but they were stopped by fire from concealed machine guns. However, by 13:30, fighting in the streets of the town was underway, when the Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment continued their steady advance, and the 5th Light Horse Regiment entered the southern part of the town. At 14:30, a second regiment of 1st Light Horse Brigade was ordered to reinforce the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade's left. The Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiment advanced to a position from which they were able to enfilade the defenders in the Citadel, and shortly afterwards the 10th Squadron, with a troop of the 8th Squadron, attacked and "stormed" the Citadel.[78][81][88] By 15:00 the Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiment was in Amman and, with the 5th Light Horse Regiment, were "hunting out snipers and capturing prisoners."[88]

By 16:30 on 25 September the Anzac Mounted Division, captured Amman along with between 2,500 and 2,563 prisoners, 300 sick, ten guns (three of which were heavy), and 25 machine guns.[57][89][90] The mounted infantry method of systematically "galloping to points of vantage and bringing fire to bear on the flanks of such machine gun nests," combined with quick outflanking of machine guns eventually won all obstacles, and the opposition was broken.[91]

During the Third Transjordan attack, Chaytor's Force suffered 139 casualties, consisting of 27 killed, 7 missing and 105 wounded. Of these the Anzac Mounted Division suffered 16 men killed and 56 wounded, while the 2nd Battalion British West Indies Regiment suffered 41 casualties.[92][93][94] Historian Earl Wavell notes that "the Anzac Mounted Division here ended a very fine fighting record. It had taken a gallant part in practically every engagement since the EEF had set out from the Canal two and a half years previously."[95]

Aftermath

By the evening of 25 September, the 1st Light Horse Brigade held the Amman railway station area, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade held the area to the south, while the 2nd Light Horse Brigade bivouacked on the western slope of Hill 3039.[78] A squadron from the Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment was sent to Madeba where they captured a number of prisoners and a very large amount of grain. Emergency rations were supplemented by food bought from the inhabitants.[96][97] The 20th Indian Brigade along with the VIIIXX RHA Brigade and 1st Battalion British West Indies Regiment were ordered to march to Amman, leaving the 39th Royal Fusiliers at Suweileh to take over the defence of Es Salt.[78][98]

Allenby wrote to Henry Wilson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff at the War Office regarding his plans for the Anzac Mounted Division: "I shall leave one cavalry division in the Amman area to operate against and cut off the enemy retreating Northwards from Ma'an, and thereafter it will proceed to Damascus and rejoin Desert Mounted Corps."[99]

Pursuit of Fourth Army north of Amman

Only a rearguard of the Fourth Army was captured at Amman. The remainder of the garrison was already retreating northwards, following orders received from Liman von Sanders on 21 September, four days before Chaytor's attack. Those who had escaped by train, before the line was cut by Chaytor's Force during the night of 24/25 September, were forced to detrain south of Deraa. Here they found the railway line cut by Arab Sherifial forces.[19][20][98] A retreating column of 3,000 infantry and cavalry, 300 horse transport and guns, and 600 camels was seen at Mafrak, withdrawing northwards from Amman in the early morning of 25 September. Ten Australian aircraft bombed Mafrak between 06:00 and 08:00. The railway station, a long train and several dumps were destroyed, and the railway was completely blocked. A number of trains continued to arrive at Mafrak from Amman during the day, but each was attacked by aircraft. No. 1 Squadron AFC bombed the area three times, dropping four tons of bombs and firing almost 20,000 machine gun rounds. The survivors were forced to abandon their wheeled-transport, and only a few thousand managed to escape on foot or horse towards Deraa and Damascus.[100]

The 1st Light Horse Brigade was ordered to capture the nearest water in the Wadi el Hamman 10 miles (16 km) north of Amman, to deny it to the retreating columns. A regiment of the brigade captured Kalaat ez Zerka railway station, 12 miles (19 km) north east of Amman. Here, "after a short action" on 26 September, they captured 105 prisoners and one gun.[98][101][102] Aircraft guided the 1st Light Horse Brigade to the location of an Ottoman force on 27 September, which the aircraft then machine gunned. Subsequently the light horsemen captured 300 prisoners and two machine guns. By evening, they had captured the water at Wadi el Hamman, while one regiment occupied Kalaat ez Zerka.[98][101][103] The next day the 1st Light Horse Regiment advanced to Qalat el Mafraq, 30 miles (48 km) north north east of Amman. Here they captured several trains, one Red Crescent train full of wounded, along with 10 officers and 70 other ranks found sick at Kh es Samra.[98][101] Woodward claims the Red Crescent train at Qalat el Mafraq had been looted and all the sick and wounded killed.[104]

A total of 6,000 or 7,000 retreating soldiers from the three Ottoman armies, mostly from the Fourth Army, escaped the combined encirclement by the XX Corps, the XXI Corps, the Desert Mounted Corps and Chaytor's Force, to retreat towards Damascus.[100]

Capture of Fourth Army units south of Amman

Chaytor's Force blocked the road and railway at Amman and prepared to intercept the Ottoman II Corps of the Fourth Army, which was retreating north from Ma'an. This large Ottoman force which had garrisoned the towns and railway stations on the southern Hejaz Railway, was reported to be 30 miles (48 km) south of Amman on the evening of 25 September, advancing quickly north towards Chaytor's Force.[78][98][105][106]

Consisting of Ottoman, Arab and Circassian soldiers,[Note 15] the II Corps had three options: to pass to the east of Amman along the Darb el Haj direct to Damascus, although water would be a problem in that desert region, to attack Chaytor's Force at Amman, or to move westwards, to try to get to the Jordan Valley. Patterson's Column was ordered to entrench Shunet Nimrin, Es Salt and Suweileh in case they moved westwards.[Note 16] On the Royal Fusiliers' right the 2nd Light Horse Brigade closely guarded the country to the south, in particular the Madaba to Naur to Ain Hummar road across the plateau, with a strong detachment occupying Ain es Sir.[98][107] The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade sent a detachment at about midday on 26 September to investigate a report of Ottoman and German soldiers with guns at Er Rumman, but none were found. They subsequently sent a second detachment east of Amman to watch the Darb el Haj.[101] The 20th Indian Brigade of infantry arrived after dark on 26 September to take over garrison duties at Amman.[108][Note 17]

The 2nd Light Horse Brigade was ordered to blow up the railway line as far to the south as they could, in order to obstruct and delay the northward movement of the Ottoman II Corps. They cut the railway line just north of Ziza Station. By 08:30 on 27 September, they had captured some Ottoman soldiers south of Leban Station, 12 miles (19 km) to the south of Amman. One of the prisoners said the advanced guard of a 6,000 strong retreating column had reached Kastal, 15 miles (24 km) south of Amman.[98][101][102] Aircraft located the Ottoman Southern Force at 06:55 on 28 September at Ziza, about 20 miles (32 km) south of Amman, where three trains were in the station. A message dropped at 15:15 called on them to surrender. They were warned that all water north of Kastal was in EEF hands, and that they would be bombed the next day, if they refused to surrender.[101][109] No answer had been received by 08:45 on 29 September, and arrangements were made for the bombing to be carried out in the afternoon.[101]

The 5th Light Horse Regiment (2nd Light Horse Brigade), meanwhile had reached 3 miles (4.8 km) north of Ziza at 10:30, where an Ottoman officer delivered a letter from the commander of the II Corps. The 5th Light Horse regimental commander was informed at 11:40 by 2nd Light Horse Brigade headquarters that, unless the Ottoman force surrendered, they would be bombed at 15:00. Negotiations for a surrender began at 11:45, and the 5th Light Horse Regiment moved across the railway to within 700 yards (640 m) of the Ottoman force, which was surrounded by Bedouin. Reports were received by 12:45 that the Ottoman force at Ziza would surrender, and the bombing raid was cancelled. The remainder of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade was ordered to "make a forced march" from Amman to Ziza, and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade was ordered to follow at dawn the next day. The 7th Light Horse Regiment (2nd Light Horse Brigade) arrived at Ziza late in the afternoon.[80][101][110][111] The remainder of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, less details and patrols, left Amman at 13:45. They moved slowly at first, through hilly and stony country between Amman and Leban, then trotted to Ziza, where they arrived at 17:20. The Bedouin force which surrounded the Ottoman II Corps were Beni Sakhr Bedouin Arabs. They demanded that the Ottoman force be handed over to them. This was refused, and after the arrival of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, the Beni Sakhr force became openly hostile.[80][104][Note 18]

Chaytor arrived at about 17:00, and informed the Ottoman commander that his soldiers were to "be prepared to defend" themselves for the coming night.[111][112] The Ottoman commander Colonel Kaaimakan Ali Bey Whahaby agreed to be a hostage in exchange for the cooperation of his men with Chaytor's Force, and left for Amman with Chaytor at 17:30.[80][113] The 5th and 7th Light Horse Regiments galloped through the encircling Arabs into the Ottoman position, and placed troops in position at intervals in the Ottoman line, where they remained until the morning.[80][93][114] Two small clashes between Beni Sakhr Arabs and Ottomans occurred before dark, but a cordon was put round the Ottoman force after the arrival of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade. The Beni Sakhr were warned to keep back, though they attempted to raid the hospital.[115][116] During the night, several attacks by the Beni Sakhr Arab force were driven off by Ottoman machine gun fire and light horse rifles.[80][113]

The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade arrived at 05:30 on 30 September to take over the position and the care of the 534 sick, as well as collecting the 14 guns, 35 machine guns, two automatic rifles, three railway engines, 25 railway trucks, lorries and large amounts of ammunition and stores. After assurances by Brigadier General Ryrie commanding the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, that the sick and wounded Ottoman soldiers would be cared for, the Ottoman force concentrated at dawn near Ziza railway station while the light horsemen took the bolts from the Ottoman rifles. Two Anatolian battalions remained armed in case the Beni Sakhr attacked during the march. The 5th Light Horse Regiment marched between 4,068 and 4,082 prisoners, including walking wounded, north to Amman. They were followed by 502 sick.[80][113][114][117]

All prisoners were mustered. Walking sick cases were collected under shelter of the station buildings, and cot cases were transferred to 2nd Light Horse Field Ambulance cacolets. The prisoners escorted by 5th Light Horse Regiment, less one squadron at Amman with one squadron 7th Light Horse attached, moved off to Amman at 07:15. All arms and equipment were collected and put in railway trucks. This task was finished by 15:30. The Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiment remained to guard the sick until transport was organised. One hundred sick walking cases were sent on to Amman in New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade transport wagons and the 2nd Light Horse Brigade commenced its return journey to Amman. They arrived at 21:00, while the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade remained in charge at Ziza.[80][116]

Chaytor's Force's total captures from the beginning of operations to 30 September were 10,322 prisoners, 57 guns including one 5.9-inch gun, three 5.9-inch howitzers, one anti aircraft gun, ten 10 cm guns, 32 77 mm guns, six 75 mm guns, two 3-inch guns and two 13 pounder HAC guns, 147 machine guns, 13 automatic rifles including one Hotchkiss rifle and one Lewis gun, two wireless sets, 11 railway engines, 106 railway rolling stock, 142 vehicles and large quantities of artillery shells, small arms ammunition (SAA) and other material.[94][113]

Medical establishments and evacuations

The mobile sections of the field ambulances followed their brigades to Es Salt with their camel transport. They travelled up the Umm esh Shert and Jisr ed Damieh tracks, while their wheeled transport followed by the Shunet Nimrim road.[67] A divisional collecting station was established at Suweileh, during the Second Battle of Amman, by the immobile section of the 1st Light Horse Field Ambulance and the Anzac (No. 7) Sanitary Section. Both of these units arrived from Jerusalem early on 25 September, following the wheeled supply vehicles along the Shunet Nimrin road. Subsequently a dressing-station was opened in the ruins of the Roman amphitheatre at Amman. There, 268 sick and wounded light horsemen were admitted up to 30 September and evacuated from Amman by motor ambulance wagons. Two Ottoman hospitals in the town were found to hold 480 patients, a number which quickly grew to more than 1,000. These patients and the Ottoman medical staff were evacuated to Jerusalem by motor lorries. There were also 1,269 British and Indian sick evacuated from Amman in the ten days between 30 September and 9 October.[118]

These large numbers of evacuations to Jericho, eight to ten hours away, travelled mostly in motor lorries. Motor ambulances were reserved for the most severe cases. The trip was broken about 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Es Salt, where the Welsh Field Ambulance fed the patients and rested them for two hours before they resumed their journey. One group of motor ambulances drove between Amman and the Welsh Field Ambulance, and a second group drove from the Welsh Field Ambulance to Jericho. Motor lorries and some cars of No. 35 Motor Ambulance Convoy evacuated the sick from the Anzac Mounted Division receiving station near Jericho to the casualty clearing station at Jerusalem.[92]

Health among the troops

Many of the troops at Amman had garrisoned the malarial Jordan Valley for over six months, during the summer. The hot, humid Jordan Valley sits at about 1,000 feet (300 m) below sea level, while the troops at Amman were now some 3,000 feet (910 m) above sea level in a climate where the nights were cold. With malaria dormant in their blood, the change of climate caused many cases of attacks of malaria fever.[84][98][Note 19] Before the returning 2nd Light Horse and New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigades reached Jerusalem on their way back to Deiran, they, along with the 1st Light Horse Brigade still the Amman area, were struck by a heavy outbreak of disease.[119] "Between 19 September and 3 November, 6920 men in Chaytor's Force were listed as sick. In the Anzac division, 1088 men were sick in September; the number trebled in the following month ... In some regiments, riderless horses were let loose and herded down into the valley like a mob of cattle."[94]

The Anzac Mounted Division evacuated more than 3,000 sick in the last three weeks of September 2700 of which were cases of malignant malaria.[120] The divisional collecting station was brought forward from Suweileh on 30 September, and at one time treated as many as 246 cases, the majority of which were seriously ill.[119] The 1st Light Horse Brigade evacuated 126 cases during the seven days following 28 September, and 239 cases by 10 October. The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade evacuated 316 cases and the 2nd Light Horse Brigade had 57 cases, many of whom suffered a high fever of 105° to 106 °F.[121] More than 700 cases of mostly malignant malaria were reported during the first 12 days of October, and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade lost about one third of its strength.[122] Of the approximately 5,000 New Zealanders, about 3,000 were either in hospital or in convalescent depots, mostly with malaria.[123]

On 21 September 1 Light Horse and the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigades accompanied by the 1st and 2nd Battalions British West Indies Regiment advanced to the Jisr ed Damieh. The surrounding area was swampy ground where no mosquito management had been carried out. "The air was full of hordes of peculiarly aggressive and blood–thirsty mosquitoes, laden with as subsequent events proved the parasites of malignant malaria." While the other units advanced to Es Salt and Amman, the 2nd Battalion remained to guard the bridge and was subsequently virtually the whole unit was infected with malaria. By 19 October 726 soldiers from this unit, had been evacuated with malignant malaria. Within the units of Chaytor's Force which moved to Es Salt and Amman cases of malignant malaria began to appear in much smaller numbers on 28 September and up to 10 October 2 Light Horse Brigade which had not been in the Jisr ed Damieh area evacuated 57 soldiers compared with 239 from the 1st Light Horse Brigade and 316 from the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade.[124]

To people accustomed to ordinary benign tertian malaria the serious and dramatic nature of the malignant type was most alarming. The men attacked were suddenly prostrated in high fever, 105° and 106 °F (41 °C). being frequently reported, they were often delirious and occasionally maniacal. Unless treated immediately and efficiently with quinine the mortality was high.

Of the many hundreds sent to hospital with malaria, many died, many recovered in hospital but later suffered a relapse and went to hospital again, many men were invalided home as a result of malaria, with their health badly undermined.[125] With so many men sick amongst the British Empire forces, it became common for one man to be placed in charge of eight horses. At this time, the horses were fed newly threshed barley, which resulted in the deaths of 15 horses in Chaytor's Force, while a further 160 became seriously ill.[121]

Return to Richon le Zion

The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade returned from Ziza to Amman between 1 and 2 October, then continued on to Ain es Sir on 3 October and returned to the Jordan Valley the next day. At Ain es Sir, the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment captured a number of Circassians "suspected of involvement in the May attack and escorted them to Jerusalem for trial."[126][127][Note 20]

The brigade left the Jordan Valley after three days at Jericho, bivouacking at Tallat ed Dumm on 8 October. They paused at midday on 9 October at the Mount of Olives, near Bethany, then "rode down into the Valley of Jehosophat for the last time, past the Garden of Gethsemane, up round the old walls and then through the streets of Jerusalem, past the Jaffa Gate, on to the Hebron road." The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade rested for a few days near Jerusalem, then returned to Richon le Zion on 14 October to rest and recuperate.[123][126][128]

Notes

- ↑ The Ghoraniyeh bridgehead was just 15 miles (24 km) from Jerusalem direct. [Maunsell 1926 p. 194]

- ↑ Nazareth has been mentioned as the objective of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, who were to "await the retreating Turks beginning to stream back through the Dothan pass". [Keogh 1955 p. 248]

- ↑ It has been stated that the Fourth Army began its withdrawal towards Damascus as a consequence of the loss of Samakh on 25 September. [Keogh 1955 p. 252]

- ↑ Ross Smith was no relation to Charles Kingsford Smith, with whom Ross and his brother Keith flew after the war. "Reaching Down Under: Record Setting Flights to Australia". Archived from the original on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ↑ The only available German and Ottoman sources are Liman von Sanders' memoir and the Asia Corps' war diary. Ottoman army and corps records seem to have disappeared during their retreat. [Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 494–5]

- ↑ The commander has also been referred to as Cemal, [Erickson 2001 p. 196] Cemal Kucjuk Pasha [Kinloch 2007 p. 303] and Djemal the Lesser. [Bruce 2002 p. 236] [Carver 2003 p. 232]

- ↑ The Fourth Army had been headquartered at Es Salt during the Second Transjordan attack at the end of April, having moved forward from Amman after the First Transjordan attack in March/April.

- ↑ This Composite Division of a group of German battalions is not identified in any more detail by any of the sources quoted.

- ↑ The Ottoman 53rd Division and the British Empire 53rd Division both took part in the Battle of Nablus.

- ↑ This was the second time that a commander of the Ottoman 53rd Division had been captured by the New Zealanders. The first occurred at Gaza in March 1917. [Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 551] [Hill 1978 p. 173]

- ↑ Liman von Sanders was very critical of Jevad's intervention, which considerably weakened the Samakh position, but von Oppen would have had to break through the 4th Cavalry Division's piquet line across the Esdrealon Plain from Afulah to Beisan, to get to Samakh. [Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 521, 546]

- ↑ Falls refers to four columns. [Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 553]

- ↑ One source claims the raid took place during the night of 23/24 September. [Powles 1922 pp. 249–50]

- ↑ "The memory of those four days of bitter fighting [during the First Transjordan attack on Amman] in the rain and cold were yet fresh in everyone's memory." [Powles 1922 p. 250]

- ↑ The inhabitants of the region, from Beersheba to Jericho, varied greatly in their background, religious beliefs and political outlook. The population was mainly Arab of the Sunni branch of Islam, with some Jewish colonists and Christians. At Nablus, they were almost exclusively Moslems excepting the less than 200 members of the Samaritan sect of original Jews. To the east of the Jordan Valley in the Es Salt district were Syrian and Greek Orthodox Christians, and near Amman, Circassians and Turkmans. [GB Army EEF Handbook 9/4/18 p. 61]

- ↑ Patterson's Column, which was formed at 15:00 on 22 September by the 38th and 39th Battalions Royal Fusiliers under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Patterson, ceased to exist at 12:15 on 28 September. [Anzac MD War Diary pp. 4, 6]

- ↑ On 30 September, Allenby reported to the War Office his intentions for the occupied area: "I am not extending the existing Occupied Enemy Territory Administration to places east of Jordan in the "B" area, such as Es Salt and Amman, but until such time as an Arab administration be formed later, I am merely appointing a British officer to safeguard the interests of the inhabitants." [Hughes 2004 p. 191]

- ↑ These were not Feisal's men, but Bedouin of the Beni Sakhr tribe, who had agreed to co–operate with the EEF during the Second Transjordan attack in April, but were out of the area when the attack occurred. [Wavell 1968 p. 222]

- ↑ Many of Chaytor's Force became sick towards the end of operations, and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade lost almost 60 per cent of its strength sick to hospital during the period. [Moore 1920 p. 151]

- ↑ This incident occurred during the First Transjordan attack, on 1 April at 07:45, during the retreat from Amman. See First Transjordan attack on Amman.

Citations

- ↑ Bruce 2002 p. 203

- 1 2 Powles 1922 pp. 222–3

- ↑ Hughes 2004 pp. 167–8

- ↑ Hughes 2004 p. 160

- ↑ Allenby letter to Wilson 24 July 1918 in Hughes 2004 pp. 168–9

- ↑ Hamilton 1996 p. 135–6

- ↑ Mitchell 1978 pp. 160–1

- ↑ Maunsell 1926 p. 212

- 1 2 Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 547

- ↑ Gullett 1919 p. 32

- ↑ Maunsell 1926 p. 199

- 1 2 3 Hill 1978 p. 162

- 1 2 3 4 Anzac Mounted Division General Staff War Diary AWM4-1-60-31 Part 2 Appendix 38 p. 1

- 1 2 3 Falls 1930 Vol. 2. pp. 547–8

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 548

- ↑ Blenkinsop 1925 p. 241

- ↑ Massey 1920 pp. 155–7

- ↑ Wavell 1968 p. 211

- 1 2 3 Keogh 1955 p. 251

- 1 2 Wavell 1968 p. 223

- 1 2 Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 511, 545

- ↑ Gullett 1919 pp. 25–6

- 1 2 3 Powles 1922 pp. 233–4

- ↑ Powles 1922 p. 231

- ↑ Bou 2009 p. 194

- ↑ Kinloch, p.321

- ↑ Anzac Mounted Division Admin Staff, Headquarters War Diary 30 September 1918 AWM4-1-61-31

- 1 2 3 Downes 1938 p. 721

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 460

- ↑ Cutlack 1941 pp. 151–2

- ↑ Carver 2003 pp. 225, 232

- ↑ Maunsell 1926 p. 213

- 1 2 Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 548–9

- ↑ Powles 1922 pp. 231, 235

- 1 2 Blenkinsop 1925 p. 242

- 1 2 Pugsley 2004 p. 143

- 1 2 Bruce 2002 p. 235

- 1 2 Anzac Mounted Division General Staff War Diary AWM4-1-60-31 Part 2 Appendix 38 pp. 0–1 (E1/71-72)

- ↑ Wavell 1968 p. 199

- 1 2 3 Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 549

- ↑ Erickson 2007 pp. 132, 2001 p. 196

- 1 2 Erickson 2001 p. 196

- ↑ Keogh 1955 pp. 241–2

- ↑ Wavell 1968 p. 195

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 674

- 1 2 3 Gullett 1919 p. 39

- 1 2 3 Anzac Mounted Division General Staff War Diary AWM4-1-60-31 Part 2 Appendix 38 pp. 2–3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade War Diary AWM4-35-12-41

- ↑ Cutlack 1941 pp. 155–6

- ↑ Cutlack 1941 p. 158

- ↑ Wavell 1968 p. 220

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 511–2, 675

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 511–2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Anzac Mounted Division General Staff War Diary AWM4-1-60-31 Part 2 Appendix 38 p. 3

- 1 2 3 Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 550

- 1 2 Powles 1922 p. 245

- 1 2 3 4 Wavell 1968 p. 221

- 1 2 Cutlack 1941 p. 162

- ↑ Falls p. 551

- 1 2 Powles 1922 p. 246

- ↑ Powles 1922 pp. 245–6

- ↑ Moore 1920 pp. 148–50

- 1 2 Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 552

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Anzac Mounted Division General Staff War Diary AWM4-1-60-31 Part 2 Appendix 38 p. 4

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 551–2

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 546

- 1 2 3 4 Downes 1938 p. 722

- ↑ Wavell 1968 pp. 220, 223

- ↑ Cutlack 1941 p. 165

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 552, note

- 1 2 Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 552–3

- 1 2 3 4 Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 553

- 1 2 3 Powles 1922 p. 248

- ↑ Gullett 1919 p.52

- 1 2 Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 553–4

- 1 2 Cutlack 1941 pp. 165–6

- ↑ Anzac Mounted Division General Staff War Diary AWM4-1-60-31 Part 2 Appendix 38 pp. 4–5

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Anzac Mounted Division General Staff War Diary AWM4-1-60-31 Part 2 Appendix 38 p. 5

- ↑ Cutlack 1941 p. 166

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 2nd Light Horse Brigade War Diary AWM4-10-2-45

- 1 2 3 4 Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 554

- ↑ Powles 1922 pp. 249–50

- ↑ Hughes 2004 pp. 183–4

- 1 2 Moore 1920 p. 151

- 1 2 Powles 1922 p. 250

- ↑ Powles 1922 p. 252

- ↑ Kinloch 2007 p. 315

- 1 2 3 Powles 1922 p. 251

- ↑ DiMarco 2008 p. 332

- ↑ Kinloch 2007 p. 316

- ↑ Powles 1922 pp. 252, 257

- 1 2 Downes 1938 pp. 723–4

- 1 2 Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 559

- 1 2 3 Kinloch 2007 p. 321

- ↑ Wavell 1968 p. 222

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 554–5

- ↑ Powles 1922 pp. 255–6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 555

- ↑ Allenby to Wilson 25 September 1918 in Hughes 2004 p. 188

- 1 2 Cutlack 1941 pp. 166–7

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Anzac Mounted Division General Staff War Diary AWM4-1-60-31 Part 2 Appendix 38 p. 6

- 1 2 Powles 1922 p. 253

- ↑ Powles 1922 p. 254

- 1 2 Woodward 2006 p. 202

- ↑ Wavell 1968 p. 221–2

- ↑ Moore 1920 pp.160–1

- ↑ Anzac Mounted Division General Staff War Diary AWM4-1-60-31 Part 2 Appendix 38 pp. 5–6

- ↑ 2nd LHB War Diary

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. pp. 555–6

- ↑ Powles 1922 pp. 254–5

- 1 2 Kinloch 2007 p. 318

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 556–7

- 1 2 3 4 Anzac Mounted Division General Staff War Diary AWM4-1-60-31 Part 2 Appendix 38 p. 7

- 1 2 Kinloch 2007 pp. 318–9

- ↑ Anzac Mounted Division General Staff War Diary AWM4-1-60-31 Part 2 Appendix 38 pp. 6–7

- 1 2 Powles 1922 p. 255

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 558–9

- ↑ Downes 1938 pp. 722–3

- 1 2 Downes 1938 p. 723

- ↑ Preston 1921 p. 246

- 1 2 Blenkinsop 1925 pp. 243–4

- ↑ Pugsley 2004 p. 144

- 1 2 Moore 1920 pp. 166–7

- 1 2 Powles 1922 pp. 261–2

- ↑ Moore 1920 p. 142

- 1 2 Kinloch 2007 p. 323

- ↑ Powles 1922 p. 256

- ↑ Powles 1922 pp. 256, 263

References

- "2nd Light Horse Brigade War Diary". First World War Diaries AWM4, 10-2-45. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. September 1918. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade Headquarters War Diary". First World War Diaries AWM4, 35-1-41. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. September 1918. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "Anzac Mounted Division General Staff War Diary". First World War Diaries AWM4, 1-60-31 Part 2. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. September 1918. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "Anzac Mounted Division Admin Staff, Headquarters War Diary". First World War Diaries AWM4, 1-61-31. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. September 1918.

- Baly, Lindsay (2003). Horseman, Pass By: The Australian Light Horse in World War I. East Roseville, Sydney: Simon & Schuster. OCLC 223425266.

- Blenkinsop, Layton John; Rainey, John Wakefield, eds. (1925). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents Veterinary Services. London: HM Stationers. OCLC 460717714.

- Bou, Jean (2009). Light Horse: A History of Australia's Mounted Arm. Australian Army History. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19708-3.

- Bruce, Anthony (2002). The Last Crusade: The Palestine Campaign in the First World War. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5432-2.

- Carver, Michael, Field Marshal Lord (2003). The National Army Museum Book of The Turkish Front 1914–1918: The Campaigns at Gallipoli, in Mesopotamia and in Palestine. London: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-283-07347-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cutlack, Frederic Morley (1941). The Australian Flying Corps in the Western and Eastern Theatres of War, 1914–1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. VIII (11th ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 220900299.

- DiMarco, Louis A. (2008). War Horse: A History of the Military Horse and Rider. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing. OCLC 226378925.

- Downes, Rupert M. (1938). "The Campaign in Sinai and Palestine". In Butler, Arthur Graham (ed.). Gallipoli, Palestine and New Guinea. Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, 1914–1918: Volume 1 Part II (2nd ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. pp. 547–780. OCLC 220879097.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2001). Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War: Forward by General Hüseyiln Kivrikoglu. No. 201 Contributions in Military Studies. Westport Connecticut: Greenwood Press. OCLC 43481698.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2007). Gooch, John; Reid, Brian Holden (eds.). Ottoman Army Effectiveness in World War I: A Comparative Study. No. 26 of Cass Series: Military History and Policy. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-96456-9.

- Falls, Cyril; Becke (maps), A. F. (1930). Military Operations Egypt & Palestine from June 1917 to the End of the War. Official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence: Volume 2 Part II. London: HM Stationery Office. OCLC 256950972.

- Gullett, Henry S.; Barnet, Charles; Baker, David, eds. (1919). Australia in Palestine. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. OCLC 224023558.

- Hill, Alec Jeffrey (1978). Chauvel of the Light Horse: A Biography of General Sir Harry Chauvel, GCMG, KCB. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. OCLC 5003626.

- Hughes, Matthew, ed. (2004). Allenby in Palestine: The Middle East Correspondence of Field Marshal Viscount Allenby June 1917 – October 1919. Army Records Society. Vol. 22. Phoenix Mill, Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3841-9.

- Keogh, Eustace Graham; Joan Graham (1955). Suez to Aleppo. Melbourne: Directorate of Military Training by Wilkie & Co. OCLC 220029983.

- Kinloch, Terry (2007). Devils on Horses: In the Words of the Anzacs in the Middle East, 1916–19. Auckland: Exisle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-908988-94-5.

- Massey, William Thomas (1920). Allenby's Final Triumph. London: Constable & Co. OCLC 345306.

- Maunsell, E. B. (1926). Prince of Wales' Own, the Seinde Horse, 1839–1922. Regimental Committee. OCLC 221077029.

- Moore, A. Briscoe (1920). The Mounted Riflemen in Sinai & Palestine: The Story of New Zealand's Crusaders. Christchurch: Whitcombe & Tombs. OCLC 561949575.

- Powles, C. Guy; A. Wilkie (1922). The New Zealanders in Sinai and Palestine. Official History New Zealand's Effort in the Great War. Vol. III. Auckland: Whitcombe & Tombs. OCLC 2959465.

- Preston, Richard Martin Peter (1921). The Desert Mounted Corps: An Account of the Cavalry Operations in Palestine and Syria 1917–1918. London: Constable & Co. OCLC 3900439.

- Pugsley, Christoper (2004). The Anzac Experience: New Zealand, Australia and Empire in the First World War. Auckland: Reed Books. ISBN 978-0-7900-0941-4.

- Wavell, Field Marshal Earl (1968) [1933]. "The Palestine Campaigns". In Sheppard, Eric William (ed.). A Short History of the British Army (4th ed.). London: Constable & Co. OCLC 35621223.

- Woodward, David R. (2006). Hell in the Holy Land: World War I in the Middle East. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2383-7.

Further reading

- Carey, Gordon Vero; Scott, Hugh Sumner (2011). An Outline History of the Great War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-64802-9.