| Traffic | |

|---|---|

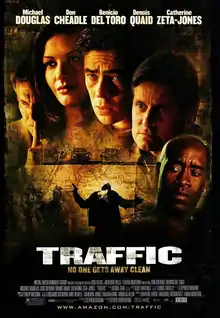

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Steven Soderbergh |

| Screenplay by | Stephen Gaghan |

| Based on | Traffik by Simon Moore |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Peter Andrews |

| Edited by | Stephen Mirrione |

| Music by | Cliff Martinez |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | USA Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 147 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $48 million[1] |

| Box office | $207.5 million[2] |

Traffic is a 2000 American crime drama film directed by Steven Soderbergh and written by Stephen Gaghan. It explores the illegal drug trade from several perspectives: users, enforcers, politicians, and traffickers. Their stories are edited together throughout the film, although some characters do not meet each other. The film is an adaptation of the 1989 British Channel 4 television series Traffik. The film stars an international ensemble cast, including Don Cheadle, Benicio del Toro, Michael Douglas, Erika Christensen, Luis Guzmán, Dennis Quaid, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Jacob Vargas, Tomas Milian, Topher Grace, James Brolin, Steven Bauer, and Benjamin Bratt. It features both English and Spanish-language dialogue.

20th Century Fox, the original financiers of the film, demanded that Harrison Ford play a leading role and that significant changes to the screenplay be made. Soderbergh refused and proposed the script to other major Hollywood studios; it was rejected because of the three-hour running time and the subject matter—Traffic is more of a political film than most Hollywood productions.[3] USA Films, however, liked the project from the start and offered the filmmakers more money than Fox. Soderbergh operated the camera himself and adopted a distinctive color grade for each storyline so that audiences could tell them apart.

Traffic was released in the United States on December 27, 2000, and received critical acclaim for Soderbergh's direction, the film's style, complexity, messages, and the cast's performances (particularly del Toro's). Traffic earned numerous awards, including four Oscars (from five nominations): Best Director for Steven Soderbergh, Best Supporting Actor for Benicio del Toro, Best Adapted Screenplay for Stephen Gaghan and Best Film Editing for Stephen Mirrione. It was also a commercial success with a worldwide box-office revenue total of $207.5 million, well above its estimated $46 million budget.

In 2004, USA Network ran a miniseries—also called Traffic—based on the film and the 1989 British television series.

Plot

Mexico storyline

In Mexico, police officer Javier Rodriguez and his partner Manolo Sanchez stop a drug transport and arrest the couriers. General Salazar, a high-ranking Mexican official, interrupts their arrest and decides to hire Javier. Salazar instructs him to apprehend Francisco Flores, a hitman for the Tijuana Cartel, headed by the Obregón brothers.

In Tijuana, under torture, Flores gives Salazar the names of important members of the Obregón cartel, who are arrested. Javier's and Salazar's efforts begin to cripple the Obregón brothers' cocaine outfit, but Javier soon discovers Salazar is a pawn for the Juárez Cartel, the rival of the Obregón brothers. That entire portion of Salazar's anti-drug campaign is a fraud, as he is only wiping out the competition.

Sanchez attempts to sell the information of Salazar's true affiliation to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), but Salazar discovers his plot and has him murdered in the desert with Javier being forced to watch; no longer able to handle working for Salazar, Javier arranges a deal with the DEA. In exchange for his testimony, Javier requests electricity in his neighborhood so the youngsters can play baseball at night rather than be tempted by street gangs and crime. Salazar's secrets are revealed, and he is arrested.

Javier explains to the media the widespread corruption in the police force and army. Later, Javier watches as children play baseball at night in their new stadium.

Wakefield storyline

Robert Wakefield, a conservative Ohio judge, is appointed to head the President's Office of National Drug Control Policy, taking on the title of drug czar. His predecessor and several influential politicians warn Wakefield that the War on Drugs is unwinnable. Meanwhile, Robert's teenage daughter, Caroline, an honors student, has been using cocaine, methamphetamine, and heroin. This develops into a drug addiction after her boyfriend Seth introduces her to freebasing. Caroline, Seth, and Vanessa are all arrested when a fellow student overdoses on drugs, and they try to dump him anonymously at a hospital. As Robert and his wife Barbara struggle to deal with the problem, of which Barbara has secretly known for over six months.

Robert ends up being caught between his demanding new position and difficult family life. On a visit to Mexico, he is encouraged by Salazar's successful efforts in hurting the Obregón brothers. Returning to Ohio, Robert learns that Caroline has run away to Cincinnati, and no one knows her exact location. She steals from her parents to procure money for drugs.

Robert drags Seth along as he begins to search Cincinnati for his daughter. After a drug dealer who is prostituting Caroline refuses to reveal her whereabouts, Robert breaks into a seedy hotel room. He finds a semi-conscious Caroline in the company of an older man. He breaks down in tears as Seth quietly leaves. Robert returns to Washington, D.C., to give his prepared speech on a "10-point plan" to win the war on drugs. Halfway through the speech, he falters. Realizing how futile his project is, he tells the press that the War on Drugs sometimes implies a war even on one's own family members, which he cannot endorse. He then exits the press conference and takes a taxi to the airport. Robert and Barbara attend Narcotics Anonymous meetings with their daughter to support her and others.

Ayala/DEA storyline

In San Diego, an undercover DEA investigation led by Montel Gordon and Ray Castro leads to the arrest of Eduardo Ruiz, a high-stakes dealer posing as a fisherman. Ruiz decides to take the road to immunity by giving up his boss: drug lord Carl Ayala, the biggest distributor for the Obregón brothers in the United States. Ayala is indicted by a tough prosecutor, hand-selected by Robert Wakefield to send a message to the Mexican drug organizations.

As the trial against Ayala begins, his pregnant wife Helena learns of her husband's true profession from his associate, Arnie Metzger. Facing the prospect of life imprisonment for her husband and death threats against her only child, Helena decides to hire Francisco Flores to assassinate Eduardo Ruiz; she knows killing Ruiz will effectively end the trial nolle prosequi. Flores plants a car bomb on a DEA car in an assassination attempt against Ruiz. Shortly after planting the bomb, Flores is assassinated by a sniper in retaliation for his cooperation with General Salazar. The bomb meant to kill Ruiz instead kills Agent Castro. Gordon and Ruiz survive.

Knowing Ruiz is soon scheduled to testify, Helena makes a deal with drug lord Juan Obregón, who forgives the Ayala family's debt and has Ruiz poisoned. Ayala is released, much to the dissatisfaction of Gordon, who is still angry over Castro's death. Ayala eventually deduces that Metzger initially informed on Ruiz. In a bid for power with another drug cartel in Mexico, Metzger accepted $3 million to inform on Ruiz to the FBI and facilitate the Ayala organization's downfall. According to Ayala, Metzger was planning on taking over Ayala's empire completely. Metzger is later visited by two men with guns. Soon after Ayala's release, Gordon bursts into the Ayala home during his homecoming celebration. Bodyguards wrestle him to the ground, but Gordon surreptitiously plants a listening bug under Ayala's desk. Gordon is forced from the property, smiling as he walks away.

Relationship to actual events

Some aspects of the plotline are based on actual people and events:

- The character General Arturo Salazar is closely modeled after Mexican General Jesús Gutiérrez Rebollo, who was secretly on the payroll of Amado Carrillo Fuentes, head of the Juarez Cartel.

- The character Porfirio Madrigal is modeled after Fuentes.

- The Obregón brothers are modeled after the Tijuana Cartel's Arellano Félix brothers.[4][5][6]

At one point in the film, an El Paso Intelligence Center agent tells Robert his position, official in charge of drug control, doesn't exist in Mexico. As noted in the original script, a Director of the Instituto Nacional para el Combate a las Drogas was created by the Attorney General of Mexico in 1996.

Cast

- Benicio del Toro as Javier Rodriguez Rodríguez, officer of the Mexican police and police partner of Manolo Sanchez

- Jacob Vargas as Manolo Sanchez, officer of the Mexican police and police partner of Javier Rodriguez

- Marisol Padilla Sánchez as Ana Sanchez, Manolo's wife

- Tomas Milian as General Arturo Salazar, a corrupt general of the Mexican Army who has ties with Porfirio Madrigal, head of the powerful Juarez Cartel

- Michael Douglas as Robert Wakefield, a powerful judge from Ohio and Caroline's father

- Amy Irving as Barbara Wakefield, Robert Wakefield's wife

- Erika Christensen as Caroline Wakefield, Robert Wakefield's daughter, and an endangered drug user

- Topher Grace as Seth Abrahams, Caroline's drug-using boyfriend

- D. W. Moffett as Jeff Sheridan

- James Brolin as General Ralph Landry, Robert's predecessor

- Albert Finney as White House Chief of Staff

- Steven Bauer as Carlos Ayala, a notorious and powerful drug lord from Mexico

- Catherine Zeta-Jones as Helena Ayala, Carlos Ayala's pregnant wife

- Dennis Quaid as Arnie Metzger, Carlos Ayala's crime partner

- Clifton Collins Jr. as Francisco "Frankie Flowers" Flores, a sicario who works for the Obregón brothers, the heads of the powerful Tijuana Cartel

- Don Cheadle as Montel Gordon, DEA agent and Ray's fellow undercover partner

- Luis Guzmán as Ray Castro, DEA agent and Montel's fellow undercover partner

- Miguel Ferrer as Eduardo Ruiz, a drug dealer who works for Carlos Ayala

- Peter Riegert as Michael Adler

- Benjamin Bratt as Juan Obregón, a powerful Mexican drug lord, one of the Obregón brothers and the head of Tijuana Cartel

- Viola Davis as the Social Worker

- John Slattery as Assistant District Attorney Dan Colier

- James Pickens Jr. as The Prosecutor

- Salma Hayek as Rosario (uncredited)

Development

Steven Soderbergh had been interested in making a film about the drug wars for some time but did not want to make one about addicts.[7] Producer Laura Bickford obtained the rights to the British television miniseries Traffik (1989) and liked its structure. Soderbergh, who had seen the miniseries in 1990,[8] started looking for a screenwriter to adapt it into a film. They read a script by Stephen Gaghan called Havoc, about upper-class white kids in Palisades High School doing drugs and getting involved with gangs.[9] Soderbergh approached Gaghan to work on his film but found he was already developing a film about drugs for producer/director Edward Zwick. Bickford and Soderbergh approached Zwick, who agreed to merge the two projects and come aboard as a producer.[7]

Traffic was originally going to be distributed by 20th Century Fox, but it was put into turnaround unless actor Harrison Ford agreed to star. Soderbergh began shopping the film to other studios, but when Ford suddenly showed interest in Traffic, Fox's interest in the film was renewed; the studio took it out of turnaround.[10] Fox CEO Bill Mechanic championed the film, but he departed from the studio by the time the first draft was finished. It went back into turnaround.[11] Mechanic had also wanted to make some changes to the script, but Soderbergh disagreed[1] and decided to shop the film to other major studios. They all turned him down because they were not confident in the prospects of a three-hour film about drugs, according to Gaghan.[9] USA Films, however, had wanted to take on the movie from the first time Soderbergh approached them.[11] They provided the filmmakers with a $46 million budget, a considerable increase from the $25 million which Fox offered.[1]

Screenplay

Soderbergh had "conceptual discussions" with Gaghan while he was shooting The Limey in October 1998; they finished the outline before he went off to shoot Erin Brockovich.[7] After Soderbergh was finished with that film, Gaghan had written a first draft in six weeks that was 165 pages long.[9] After the film was approved for production, Soderbergh and Gaghan met two separate times for three days to reformat the script.[9] The draft they shot had 163 pages with 135 speaking parts and featured seven cities.[7] The film shortens the storyline of the original mini-series; a significant character arc of a farmer is taken out, and the Pakistani plotline is replaced with one set in Mexico.[8]

Casting

Harrison Ford was initially considered for the role of Robert Wakefield in January 2000 but would have had to take a significant cut in his usual $20 million salary.[12] Ford met with Soderbergh to flesh out the character. Gaghan agreed to rework the role, adding several scenes to the screenplay. On February 20, Ford turned down the role, and the filmmakers brought it back to Michael Douglas, who had turned down an earlier draft. He liked the changes and agreed to star, which helped greenlight the project.[12] Gaghan believes Ford turned down the role because he wanted to "reconnect with his action fans".[9]

The filmmakers sent out letters to many politicians, both Democrat and Republican, asking them to make cameo appearances in the film. Several of the scenes had already been shot using actors in these roles, but the filmmakers went back and reshot those scenes when real politicians agreed to be in the film.[13] Those who agreed, including U.S. Senators Harry Reid, Barbara Boxer, Orrin Hatch, Charles Grassley, and Don Nickles, and Massachusetts governor Bill Weld, were filmed in a scene that was entirely improvised.[8]

Pre-production

The project was obtained from Fox by Initial Entertainment Group and was sold to USA Films by IEG for North American rights only. Steven Soderbergh never approached USA Films, and Initial Entertainment Group fully funded the film.

After Fox dropped the film in early 2000 and before USA Films expressed interest, Soderbergh paid for pre-production with his own money.[9] USA Films agreed to give him the final cut on Traffic and also agreed to his term that all the Mexican characters would speak Spanish while talking to each other.[12] This meant that almost all of Benicio del Toro's dialogue would be subtitled. Once the studio realized this, they suggested that his scenes be shot in English and Spanish, but Soderbergh and del Toro rejected the suggestion.[12] Del Toro, a native of Puerto Rico,[14] was worried that another actor would be brought in and re-record his dialogue in English after he had worked hard to master Mexican inflections and improve his Spanish vocabulary. Del Toro remembers, "Can you imagine? You do the whole movie, bust your butt to get it as realistic as possible, and someone dubs your voice? I said, 'No way. Over my dead body.' Steven was like, 'Don't worry. It's not gonna happen.'"[12] The director fought for subtitles for the Mexico scenes, arguing that if the characters did not speak Spanish, the film would have no integrity and would not convincingly portray what he described as the "impenetrability of another culture".[8]

The filmmakers went to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and U.S. Customs early on with the script; they told them that they were trying to present as detailed and accurate a picture of the current drug war as possible.[8] The DEA and Customs pointed out inaccuracies in the script. In addition, they gave the production team access to the border checkpoint to Mexico, as shown in the film during the scene in which Wakefield and his people talk with border officials. Despite the assistance, the DEA did not try to influence the script's content.[8] Soderbergh said Traffic had influences from the films of Richard Lester and Jean-Luc Godard. He also spent time analyzing The Battle of Algiers and Z, which, according to the director, had the feeling that the footage was "caught" and not staged.[11] Another inspiration was Alan J. Pakula's film All the President's Men because of its ability to tackle serious issues while being entertaining.[15] In the opening credits of his film, Soderbergh tried to replicate the typeface from All the President's Men and the placement on-screen at the bottom left-hand corner. Analyzing this film helped the director deal with the large cast and working in many different locations for Traffic.[15]

Principal photography

Half of the first day's footage came out overexposed and unusable.[12] Before the financiers or studio bosses knew about the problem, Soderbergh was already doing reshoots. The insurers made him agree that any further mishaps resulting in additional filming would come from the director's pocket.[12] Soderbergh shot in various cities in California, Ohio, and Texas, on a 54-day schedule and came in $2 million under budget.[7] The director acted as his cinematographer under the pseudonym Peter Andrews and operated the camera himself to "get as close to the movie as I can" and to eliminate the distance between the actors and himself.[16][7] Soderbergh drew inspiration from the cinema verite style of Ken Loach's films, studying the framing of scenes, the distance of the camera to the actors, lens length, and the tightness of eyelines depending on the position of a character. Soderbergh remembers, "I noticed that there's a space that's inviolate, that if you get within something, you cross the edge into a more theatrical aesthetic as opposed to a documentary aesthetic".[7] Most of the day was spent shooting because a lot of the film was shot with available light.[11]

For the hand-held camera footage, Soderbergh used Panavision Millennium XLs that were smaller and lighter than previous cameras and allowed him to move freely.[7] He adopted a distinctive look for each to tell the three stories apart. For Robert Wakefield's story, Soderbergh used tungsten film with no filter for a cold, monochrome blue feel.[7] For Helena Ayala's story, Soderbergh used diffusion filters, flashing the film and overexposing it for a warmer feel. For Javier Rodriguez's story, the director used tobacco filters and a 45-degree shutter angle whenever possible to produce a strobe-like sharp feeling.[7] Then, he took the entire film through an Ektachrome step, which increased the contrast and grain significantly.[7] He wanted different looks for each story because the audience had to keep track of many characters and absorb a lot of information, and he did not want them to have to figure out which story they were watching.[8]

Benicio del Toro had significant input into certain parts of the film; for example, he suggested a more straightforward, concise way of depicting his character kidnapping Francisco Flores that Soderbergh ended up using.[8] The director cut a scene from the screenplay in which Robert Wakefield smokes crack after finding it in his daughter's bedroom. After rehearsing this scene with the actors, he felt that the character would not do it; after consulting with Gaghan, the screenwriter agreed, and the filmmakers cut the scene shortly before it was scheduled to be shot.[9]

Balboa Park, Downtown San Diego and La Jolla were utilized as the environment for the film.[17]

Post-production

The first cut of Traffic ran three hours and ten minutes.[7] Soderbergh cut it to two hours and twenty minutes. Early on, there were concerns that the film might get an NC-17 rating, and he was prepared to release it with that rating, but the MPAA gave it an R.[7]

Release

Box office performance

Traffic was given a limited release on December 27, 2000, in four theaters where it grossed US$184,725 on its opening weekend. It was given a wide release on January 5, 2001, in 1,510 theaters, grossing $15.5 million on its opening weekend. The film made $124.1 million in North America and $83.4 million in foreign markets for a worldwide total of $207.5 million, well above its estimated $46 million budget.[1][18]

Home media

In the United States, the film was released on DVD on May 28, 2002, by The Criterion Collection.[19] In Australia, Traffic was released on DVD by Village Roadshow, with an MA15+ rating. Despite the Australian packaging stating the length to be 124 minutes, the actual DVD version is just over 141 minutes long.

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 93% based on 223 reviews, with an average rating of 8/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Soderbergh successfully pulls off the highly ambitious Traffic, a movie with three different stories and a very large cast. The issues of ethics are gray rather than black-and-white, with no clear-cut good guys. Terrific acting all around."[20] On Metacritic the film has received an average score of 86 out of 100, based on 34 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[21] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B" on an A+ to F scale.[22]

Film critic Roger Ebert gave the film four out of four stars and wrote, "The movie is powerful precisely because it doesn't preach. It is so restrained that at one moment—the judge's final speech—I wanted one more sentence, making a point, but the movie lets us supply that thought for ourselves".[23] Stephen Holden, in his review for The New York Times, wrote, "Traffic is an utterly gripping, edge-of-your-seat thriller. Or rather it is several interwoven thrillers, each with its own tense rhythm and explosive payoff".[24] In his review for The New York Observer, Andrew Sarris wrote, "Traffic marks [Soderbergh] definitively as an enormous talent, one who never lets us guess what he's going to do next. The promise of Sex, Lies, and Videotape has been fulfilled".[25]

Entertainment Weekly gave the film an "A" rating and praised Benicio del Toro's performance, which critic Owen Gleiberman called, "haunting in his understatement, [it] becomes the film's quietly awakening moral center".[26] Desson Howe, in his review for the Washington Post, wrote, "Soderbergh and screenwriter Stephen Gaghan, who based this on a British television miniseries of the same name, have created an often exhilarating, soup-to-nuts exposé of the world's most lucrative trade".[27] In his review for Rolling Stone, Peter Travers wrote, "The hand-held camerawork – Soderbergh himself did the holding—provides a documentary feel that rivets attention".[28] However, Richard Schickel of Time, in a rare negative review, finds the film's biggest weakness to be that it contains the "cliches of a hundred crime movies" before concluding that "Traffic, for all its earnestness, does not work. It leaves one feeling restless and dissatisfied".[29] In an interview, director Ingmar Bergman lauded the film as "amazing".[30]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Recipient(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[31] | Best Picture | Marshall Herskovitz, Edward Zwick and Laura Bickford | Nominated |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Best Screenplay – Based on Material Previously Produced or Published | Stephen Gaghan | Won | |

| Best Film Editing | Stephen Mirrione | Won | |

| ALMA Awards | Outstanding Feature Film | Won | |

| Outstanding Latino Cast in a Feature Film | Won | ||

| Outstanding Soundtrack or Compilation for Television and Film | Nominated | ||

| Amanda Awards | Best Foreign Feature Film | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated |

| American Cinema Editors Awards | Best Edited Feature Film – Dramatic | Stephen Mirrione | Nominated |

| American Film Institute Awards[32] | Top 10 Movies of the Year | Won | |

| Artios Awards[33] | Outstanding Achievement in Feature Film Casting – Drama | Debra Zane | Won |

| Awards Circuit Community Awards | Best Motion Picture | Marshall Herskovitz, Edward Zwick and Laura Bickford | Nominated |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | |

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Stephen Gaghan | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | Stephen Mirrione | Runner-up | |

| Best Cast Ensemble | Won | ||

| Berlin International Film Festival[34] | Golden Bear | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated |

| Best Actor | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Black Reel Awards[35] | Best Supporting Actor | Don Cheadle | Won |

| Blockbuster Entertainment Awards[36] | Favorite Actor – Drama | Michael Douglas | Nominated |

| Favorite Supporting Actor – Drama | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Favorite Supporting Actress – Drama | Catherine Zeta-Jones | Nominated | |

| BMI Film & TV Awards | Film Music Award | Cliff Martinez | Won |

| Bodil Awards | Best American Film | Nominated | |

| Bogey Awards | Won | ||

| Boston Society of Film Critics Awards[37] | Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | 3rd Place |

| British Academy Film Awards[38] | Best Direction | Nominated | |

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Stephen Gaghan | Won | |

| Best Editing | Stephen Mirrione | Nominated | |

| British Society of Cinematographers[39] | Best Cinematography in a Theatrical Feature Film | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated |

| César Awards[40] | Best Foreign Film | Anthony Minghella | Nominated |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Awards[41] | Best Film | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Catherine Zeta-Jones | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay | Stephen Gaghan | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | |

| Chlotrudis Awards[42] | Best Movie | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Stephen Gaghan | Nominated | |

| Best Cast | Nominated | ||

| Costume Designers Guild Awards | Excellence in Contemporary Film | Louise Frogley | Nominated |

| Critics' Choice Movie Awards[43] | Top 10 Films | Won | |

| Best Picture | Nominated | ||

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh (also for Erin Brockovich) | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Stephen Gaghan | Won[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Dallas-Fort Worth Film Critics Association Awards | Top 10 Films | Won | |

| Best Film | Won | ||

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Catherine Zeta-Jones | Nominated | |

| Directors Guild of America Awards[44] | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated |

| Edgar Allan Poe Awards[45] | Best Motion Picture | Stephen Gaghan (screenplay); Simon Moore (based on the mini-series) |

Won |

| Empire Awards | Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated |

| Best Actor | Benicio del Toro | Nominated | |

| Best British Actress | Catherine Zeta-Jones | Nominated | |

| Film Critics Circle of Australia Awards | Best Foreign Film | Won | |

| Florida Film Critics Circle Awards[46] | Best Film | Won | |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh (also for Erin Brockovich) | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Gold Derby Awards | Best Supporting Actor of the Decade | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards[47] | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture | Catherine Zeta-Jones | Nominated | |

| Best Director – Motion Picture | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay – Motion Picture | Stephen Gaghan | Won | |

| Golden Reel Awards | Best Sound Editing – Dialogue & ADR, Domestic Feature Film | Larry Blake and Aaron Glascock | Nominated |

| Grammy Awards[48] | Best Score Soundtrack Album for a Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media | Cliff Martinez | Nominated |

| Humanitas Prize[49] | Feature Film | Stephen Gaghan | Nominated |

| Imagen Awards | Best Theatrical Feature Film | Nominated | |

| Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards[50] | Best Film | Won | |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Kinema Junpo Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Steven Soderbergh | Won |

| Best Foreign Language Film Director | Won | ||

| Las Vegas Film Critics Society Awards[51] | Best Director | Steven Soderbergh (also for Erin Brockovich) | Won |

| Best Actor | Michael Douglas | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Best Original Screenplay | Stephen Gaghan | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | Stephen Mirrione | Nominated | |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards[52] | Best Director | Steven Soderbergh (also for Erin Brockovich) | Won |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Runner-up | |

| Best Cinematography | Steven Soderbergh | Runner-up | |

| Manaki Brothers Film Festival | Golden Camera 300 | Nominated | |

| MTV Movie Awards | Breakthrough Female Performance | Erika Christensen | Won |

| Nastro d'Argento | Best Foreign Director | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated |

| National Board of Review Awards[53] | Top Ten Films | 2nd Place | |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh (also for Erin Brockovich) | Won | |

| National Festival of Dubbing Voices in the Shadow | Best Overall Dubbing | Nominated | |

| National Society of Film Critics Awards[54] | Best Film | 2nd Place | |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh (also for Erin Brockovich) | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio Del Toro | Won | |

| Best Screenplay | Stephen Gaghan | 3rd Place | |

| Best Cinematography | Steven Soderbergh | 3rd Place | |

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards[55][56] | Best Film | Won | |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh (also for Erin Brockovich) | Won | |

| Best Actor | Benicio del Toro | Runner-up | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Won | ||

| Online Film & Television Association Awards[57] | Best Picture | Marshall Herskovitz, Edward Zwick and Laura Bickford | Won |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Nominated | |

| Best Youth Performance | Erika Christensen | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Stephen Gaghan | Nominated | |

| Best Casting | Debra Zane | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | Stephen Mirrione | Nominated | |

| Best Sound | Nominated | ||

| Best Ensemble | Won | ||

| Best Titles Sequence | Nominated | ||

| Best Official Film Website | Nominated | ||

| Online Film Critics Society Awards[58] | Top 10 Films | 5th Place | |

| Best Picture | Nominated | ||

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Won[lower-alpha 2] | |

| Best Screenplay | Stephen Gaghan | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Stephen Mirrione | Nominated | |

| Best Ensemble | Nominated | ||

| Phoenix Film Critics Society Awards | Best Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Won | |

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Benicio del Toro | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Stephen Gaghan | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | Stephen Mirrione | Nominated | |

| Political Film Society Awards | Exposé | Nominated | |

| Prism Awards | Theatrical Feature Film | Won | |

| San Diego Film Critics Society Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Won |

| Satellite Awards[59] | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Won | |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama | Benicio del Toro | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Stephen Gaghan | Nominated | |

| Best Art Direction | Keith P. Cunningham | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Stephen Mirrione | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Cliff Martinez | Nominated | |

| Outstanding Motion Picture Ensemble | Won | ||

| Saturn Awards[60] | Best Action/Adventure/Thriller Film | Nominated | |

| Screen Actors Guild Awards[61] | Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture | Benjamin Bratt, James Brolin, Don Cheadle, Erika Christensen, Clifton Collins Jr., Benicio del Toro, Michael Douglas, Albert Finney, Topher Grace, Amy Irving, Dennis Quaid and Catherine Zeta-Jones |

Won |

| Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Southeastern Film Critics Association Awards[62] | Best Picture | 2nd Place | |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Benicio del Toro | Won | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Stephen Gaghan | Won | |

| Teen Choice Awards | Choice Movie Breakout | Erika Christensen | Nominated |

| Toronto Film Critics Association Awards[63] | Best Film | Runner-up | |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Won | |

| Best Male Performance | Benicio Del Toro | Won | |

| Turkish Film Critics Association Awards | Best Foreign Film | 2nd Place | |

| Vancouver Film Critics Circle Awards[64] | Best Film | Won | |

| Best Director | Steven Soderbergh | Won | |

| Best Actor | Benicio Del Toro | Won | |

| Village Voice Film Poll[65] | Best Supporting Performance | Won | |

| Writers Guild of America Awards[66] | Best Screenplay – Based on Material Previously Produced or Published | Stephen Gaghan | Won |

| Young Hollywood Awards | Breakthrough Male Performance | Topher Grace | Won |

| Standout Female Performance | Erika Christensen | Won | |

Top ten lists

Traffic appeared on several critics' top ten lists for 2000. Some of the notable top-ten list appearances are:[67]

- 2nd: A. O. Scott, The New York Times

- 2nd: Jami Bernard, New York Daily News[68]

- 2nd: Bruce Kirkland, The Toronto Sun[69]

- 3rd: Stephen Holden, The New York Times

- 3rd: Owen Gleiberman, Entertainment Weekly

- 3rd: Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

- 4th: Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

- 4th: Jack Mathews, New York Daily News[70]

See also

- Hyperlink cinema—the film style of using multiple interconnected storylines

- List of media set in San Diego

- Mexican Drug War

- Narco film

Notes

- ↑ Tied with Steve Kloves for Wonder Boys.

- ↑ Tied with Philip Seymour Hoffman for Almost Famous.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Dargis, Manohla (2000-12-26). "Go! Go! Go!". L.A. Weekly. Archived from the original on 2010-01-04. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ "Traffic (2000)" Archived 2015-08-15 at the Wayback Machine. Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved 2012-03-03.

- ↑ Dargis, Manohla. "Traffic: Border Wars". The Criterion Collection.

- ↑ Cason, Jim; David Brooks (2001-03-09). "Traffic, película que podría ser la crítica más severa a la lucha antidrogas de EU". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2011-05-26. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ↑ Cavallo, Ascanio (2001-03-10). "Traffic". El Mercurio (in Spanish). Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ↑ Shaw, Deborah (2005). ""You Are Alright, But...": Individual and Collective Representations of Mexicans, Latinos, Anglo-Americans and African-Americans in Steven Soderbergh's 'Traffic'". Quarterly Review of Film and Video. 22: 211–223. doi:10.1080/10509200490474339. S2CID 190712388. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Hope, Darrell (January 2001). "The 'Traffic' Report with Steven Soderbergh". DGA Magazine. Archived from the original on March 16, 2010. Retrieved 2011-08-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lemons, Stephen (2000-12-20). "Steven Soderbergh". Salon.com. Archived from the original on 2008-06-22. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Divine, Christian (2001-01-02). "Pushing Words". Creative Screenwriting. pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Ascher-Walsh, Rebecca (2000-02-15). "Red Light, Green Light". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- 1 2 3 4 Kaufman, Anthony (2001-01-03). "Interview: Man of the Year, Steven Soderbergh 'Traffic''s in Success". indieWIRE. Archived from the original on 2006-04-12. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Daly, Steve (2001-03-02). "Dope & Glory". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 2008-07-23. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ Conversations with Ross: "Featuring Sam Jaeger" Archived 2011-04-24 at the Wayback Machine. RossCarey.com. Retrieved 2012-03-03.

- ↑ Méndez-Méndez, S.; Mendez, S.M.; Cueto, G.; Deynes, N.R.; Rodríguez-Deynes, N. (2003). Notable Caribbeans and Caribbean Americans: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-313-31443-8. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- 1 2 Lyman, Rick (2001-02-16). "Follow the Muse: Inspiration to Balance Lofty and Light". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- ↑ French, Phillip (January 28, 2001). "Traffic". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ↑ Benninger, Michael (2016-03-01). "Hot Shots". Pacific San Diego. Retrieved 2022-12-10.

- ↑ "Traffic". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on 2015-08-15. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ↑ Rivero, Enrique (February 1, 2002). "USA's Traffic' Travels to Criterion Collection". hive4media.com. Archived from the original on February 25, 2002. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ↑ "Traffic (2000)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Traffic reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ↑ "Home". CinemaScore. Retrieved 2022-03-25.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (2001-01-01). "Traffic". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 2008-04-19. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ↑ Holden, Stephen (2000-12-27). "Teeming Mural of a War Fought and Lost". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ↑ Sarris, Andrew (2000-12-24). "Soderbergh, on Border Patrol, Dissects the Drug Economy". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on 2008-01-01. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ↑ Gleiberman, Owen (2001-01-05). "The High Drama". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ↑ Howe, Desson (2001-01-05). "Green Light for 'Traffic'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2021-03-20. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ↑ Travers, Peter (2001-12-18). "Traffic". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2021-03-20. Retrieved 2011-03-10.

- ↑ Schickel, Richard (2000-12-31). "Caution: Gridlock Ahead". Time. Archived from the original on 2008-04-02. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ↑ "EuroScreenwriters – Interviews with European Film Directors – Ingmar Bergman". Sydsvenskan. Archived from the original on 2016-08-26. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ↑ "The 73rd Academy Awards (2001) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

- ↑ "AFI Awards 2000". Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ↑ "Nominees/Winners". Casting Society of America. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ↑ "Berlinale: 2001 Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ↑ "Black Reel Awards – Past Nominees & Winners by Category". Black Reel Awards. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ↑ LANCE FIASCO (12 April 2001). "'NSync Takes Home Three Blockbuster Entertainment Awards". idobi Network. Archived from the original on 2016-09-11. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ↑ "BSFC Winners: 2000s". Boston Society of Film Critics. 27 July 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 2001". BAFTA. 2001. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ "Best Cinematography in Feature Film" (PDF). Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ↑ "The 2002 Caesars Ceremony". César Awards. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "1988-2013 Award Winner Archives". Chicago Film Critics Association. January 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ↑ "7th Annual Chlotrudis Awards". Chlotrudis Society for Independent Films. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ↑ "The BFCA Critics' Choice Awards :: 2000". Bfca.org. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- ↑ "53rd DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Category List – Best Motion Picture". Edgar Awards. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ↑ "2000 FFCC AWARD WINNERS". Florida Film Critics Circle. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ↑ "Traffic – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "2001 Grammy Award Winners". Grammy.com. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ↑ "Past Winners & Nominees". Humanitas Prize. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ↑ "KCFCC Award Winners – 2000-09". December 14, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ↑ "Previous Sierra Award Winners". lvfcs.org. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ↑ "The 26th Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "2000 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. 19 December 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "2000 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ Holden, Stephen (2000-12-14). "'Traffic' Captures Awards From New York Film Critics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2021-03-20. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ "5th Annual Film Awards (2000)". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ↑ "2000 Awards (4th Annual)". Online Film Critics Society. 3 January 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ↑ "International Press Academy website – 2001 5th Annual SATELLITE Awards". Archived from the original on 1 February 2008.

- ↑ "Past Saturn Awards". Saturn Awards.org. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2008.

- ↑ "The 7th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". Screen Actors Guild Awards. Archived from the original on November 1, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ↑ "2000 SEFA Awards". sefca.net. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ↑ "TFCA Awards 2000". torontofilmcritics.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-06.

- ↑ "1st Annual Award Winners". Vancouver Film Critics Circle. February 2001. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ↑ "2000 Village Voice Film Poll". Mubi. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Writers Guild Awards Winners". WGA. 2010. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ↑ "Metacritic: 2000 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 31, 2008. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ Bernard, Jami (2000-12-29). "Jami's Top 10 Movies". New York Daily News.

- ↑ Kirkland, Bruce (2000-12-29). "The Best, and the Rest". Toronto Sun.

- ↑ Mathews, Jack (2000-12-29). "Jack's Top 10 Movies". New York Daily News.

External links

- Traffic at IMDb

- Traffic at Metacritic

- Traffic at Rotten Tomatoes

- Traffic at Box Office Mojo

- Traffic at AllMovie

- Traffic: Border Wars an essay by Manohla Dargis at the Criterion Collection