| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

The status of women in Mexico has changed significantly over time. Until the twentieth century, Mexico was an overwhelmingly rural country, with rural women's status defined within the context of the family and local community. With urbanization beginning in the sixteenth century, following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire, cities have provided economic and social opportunities not possible within rural villages. Roman Catholicism in Mexico has shaped societal attitudes about women's social role, emphasizing the role of women as nurturers of the family, with the Virgin Mary as a model. Marianismo has been an ideal, with women's role as being within the family under the authority of men. In the twentieth century, Mexican women made great strides towards a more equal legal and social status. In 1953 women in Mexico were granted the right to vote in national elections.

Urban women in Mexico worked in factories, the earliest being the tobacco factories set up in major Mexican cities as part of the lucrative tobacco monopoly. Women ran a variety of enterprises in the colonial era, with the widows of elite businessmen continuing to run the family business. In the prehispanic and colonial periods, non-elite women were small-scale sellers in markets. In the late nineteenth century, as Mexico allowed foreign investment in industrial enterprises, women found increased opportunities to work outside the home. Women can now be seen working in factories, working in portable food carts, and owning their own business. “In 1910, women made up 14% of the workforce, by 2008 they were 38%”.[1]

Mexican women face discrimination and at times harassment from the men exercising machismo against them. Although women in Mexico are making great advances, they are faced with the traditional expectation of being the head of the household. Researcher Margarita Valdés noted that while there are few inequities imposed by law or policy in Mexico, gender inequalities perpetuated by social structures and Mexican cultural expectations limit the capabilities of Mexican women.[2]

As of 2014, Mexico has the 16th highest female homicide rate in the world.[3]

History

Pre-Columbian societies

Maya

The Mayan civilization was initially established during the Pre-Classic period (c. 2000 BC to 250 AD). According to the consensus chronology of Mesoamerica, many Mayan cities reached their highest state of development during the Classical period (c. 250 to 900 AD), and continued throughout the post-Classical period until the arrival of the Spanish in 1519 AD. Women within Mayan society were limited in regards to status, marriage, and inheritance. In all pre-Columbian societies, marriage was the ideal state for women beyond the age of puberty. Noble women were often married to the rulers of neighboring kingdoms, thus creating dynastic alliances[4]

Although the majority of these women had few political responsibilities, these women were vital to the political fabric of the state.[4] Elite women enjoyed a high status within their society and were sometimes rulers of city states.[4] Among a handful of female rulers were Lady Ahpo-Katum of Piedras Negras and Lady Apho-He of Palenque.[4] Although women had little political influence, Mayan glyph data include many scenes with a female participating in various public activities and genealogies trace male rulers' right to power through female members of their family.[4]

Women could not own or inherit land. They owned what could be termed feminine goods which included household objects, domestic animals, beehives, and their own clothing.[4] Women could bequeath their property, but it was gender specific and was usually not of much value.[4]

Aztec

The term 'Aztec' refers to certain ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Náhuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica from the 1300 A.D. to 1500 A.D. Women within Aztec society were groomed from birth to be wives and mothers and to produce tribute goods that each household owed. Each girl was given small spindles and shuttles to symbolize her future role in household production.[4] Her umbilical cord was buried near the fireplace of her house in the hope that she would be a good keeper of the home.[4]

Growing up, unmarried girls were expected to be virgins and were closely chaperoned to ensure their virginity stayed intact until their marriage.[4] Girls were married soon after reaching puberty[4] as marriage was the ideal state for women. It is estimated that as many as ninety-five percent of indigenous women were married.[4] Couples were expected to stay together, however Aztec society did recognize divorce, with each partner retaining their own property brought into the marriage after divorce.[4]

Similar to Mayan society, Aztec noblewomen had little choice in their marriage as it was a matter of state policy to create alliances.[4] In regards to inheritance and property rights, Aztec women were severely limited. Although women were allowed to inherit property, their rights to it were more to usage rights.[5] Property given to children was much freeing where it could be bequeathed or sold.[5]

Spanish conquest

When the Spanish conquistadores arrived in Mexico, they needed help to conquer the land. Although often overlooked in the history of the conquest, individual women facilitated the defeat of the powerful Aztec Empire. Women possessed knowledge of the land and the local language. One of the most notable women who assisted Hernán Cortés during the conquest period of Mexico was Doña Marina, or Malinche, who knew both the Nahuatl and Mayan language and later learned Spanish.[6]

Born a Nahua, or an Aztec, Marina was sold into slavery by her own people to the Mayans and eventually was given to Cortés as a payment of tribute. To Cortés, Doña Marina was a valuable asset in overthrowing the Aztec empire based in Tenochtitlán (now Mexico City) and was always seen at his side, even during battles with the Aztecs and Mayans.[6]

Malinche had become the translator and the mistress of Hernán Cortés. No matter how useful Doña Marina was to Cortés, he was “reluctant to give Doña Marina credit, referring to her as ‘my interpreter, who is an Indian woman’”. During the conquest women were viewed as objects that could be exploited by men to gain a higher standing in society. Malinche was considered a spoil of conquest to the males surrounding her and originally intended to sexually please the soldiers.[7]

Just like Malinche, many women were offered to the conquistadors as an offering because both cultures viewed females as objects to be presented to others.[8] Since few women traveled to the New World, native females were considered a treasure that needed to be Christianized. It is believed that there were ulterior motives in the Christianization of indigenous individuals, especially women. Conquistadores were quick to convert the women and distribute them amongst themselves.[9]

Spanish era

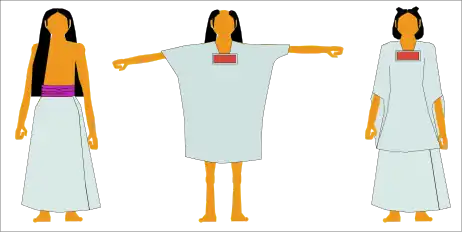

The division of social classes was essential and such divisions were expressed through the attire worn by individuals. Elite and upper-class women could afford expensive textiles imported from Spain. Due to the strong system of racial hierarchy, known as the sistema de castas, women tended to dress in accordance with their level of wealth and racial status. The racial hierarchy divided society first through separating the República de Españoles, which was the Hispanic sphere encompassing Spaniards, (Españoles) both peninsular- and American-born; Mestizos (mixed Español and Indian); Mulatos (mixed Negro and Español); Negros (Africans); and offspring of further mixed-race pairings.[10] Regardless of the social status of Indian women, she would dress in compliance with Indian customs. Wealthy females were able to purchase superior materials for clothing.

The importance placed upon social class caused purity of blood to become a factor in regards to marriage. Women were affected by these policies as it was required for both men and women to submit documents proving their blood purity. European men sought elite Mexican women to marry and have children with, in order to retain or gain a higher status in society. Problems that occurred with providing documentation in blood purity are that males were the ones who were called as a witness. Women rarely were able to defend their purity and had to rely on men from the community.[11]

Regardless of social class, women in eighteenth century Mexico City usually married for the first time between the ages of 17 and 27, with a median age of 20.5 years. Women were inclined to marry individuals belonging to the same social group as their fathers.[12]

Education for women was surrounded by religion. Individuals believed that girls should be educated enough to read the bible and religious devotionals, but should not be taught to write. When girls were provided with an education, they would live in convents and be instructed by nuns, with education being significantly limited. Of all the women who sought entry into Mexico City's convent of Corpus Christi, only 10 percent of elite Indian women had a formal education.[13]

_Cervantes_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Miguel Cabrera (painter). Doña María de la Luz Padilla y Gómez de Cervantes, ca. 1760. Brooklyn Museum.

Miguel Cabrera (painter). Doña María de la Luz Padilla y Gómez de Cervantes, ca. 1760. Brooklyn Museum. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera (painter) ca. 1750.

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera (painter) ca. 1750.

Mexican War of Independence and early republic 1810-50

The Mexican War of Independence was an armed conflict between the Mexican people and Spain. It began with the Grito de Dolores on September 16 of 1810 and officially ended on September 27 of 1821 when Spanish rule collapse and the Army of the Three Guarantees marched into Mexico City. Women participated in the Mexican War of Independence, most famously Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez, known in Mexican history as La Corregidora. Her remains were moved to the Monument to Independence in Mexico City; there are statues of her in her honor, and her face has appeared on Mexican currency. Other distinguished women of the era are Gertrudis Bocanegra, María Luisa Martínez de García Rojas, Manuela Medina, Rita Pérez de Moreno, Maria Fermina Rivera, María Ignacia Rodríguez de Velasco y Osorio Barba, better known as La Güera Rodríguez (Rodríguez the Fair);[14] and Leona Vicario.

Following independence, some women in Zacatecas raised the question of citizenship for women. They petitioned for it, saying "women also wish to have the title of citizen .. to see ourselves in the census as 'La ciudadana' (woman citizen)."[15] Independence affected women in both positive and negatives ways. Prior to the independence, women were only allowed to act as their children's guardians until the age of seven in cases of separation of widowhood. Post-independence laws allowed women to serve as guardians until the age of majority.[16] Women continued to occupy domestic service positions although economic instability led to many households ending employment of domestic servants.[16]

19th c. Liberal Reform and Porfiriato 1850-1910

As with Liberalism elsewhere, Liberalism in Mexico emphasized secular education as a path forward toward equality before the law. In the colonial era, there were limited opportunities for Mexican girls and women, but with the establishment of secular schools in the middle of the nineteenth century, girls had greater access to education, while women entered the teaching profession. Quite a number of them became advocates for women's rights, becoming active in politics, founding journals and newspapers, and attending international conferences for women's rights. Women teachers were part of the new middle class in Mexico, which also included women office workers in the private sector and government. Women also became involved in general improvement in society, including better hygiene and nutrition. Toward the end of the Porfiriato, the period when General Porfirio Díaz ruled Mexico (1876-1910), women began pressing for legal equality and the right to vote. The largest sector of Mexico's population was rural and indigenous or mixed-race, so that the movement for women's equality was carried forward by a very small sector of educated, urban women.[17]

Mexican Revolution and its Consolidation, 1910-40

The Mexican revolution began in 1910 with an uprising led by Francisco I. Madero against the longstanding regime of Porfirio Diaz. This military phase is generally considered to have lasted through 1920. Most often it is the case that women involved in war are overlooked. Although the revolution is attributed to men, it is important to note the dedication and participation women contributed, just as much as their male counterparts. Poor mestiza and indigenous women had a strong presence in the revolutionary conflict becoming camp followers often referred to in Mexico as soldaderas.[16] Nellie Campobello was one of the few women to write a first-person account of the Mexican Revolution, Cartucho.

Most often, these women followed the army when a male relative joined and provided essential services such as food preparation, tending to the wounded, mending clothing, burying the dead, and retrieval of items from the battlefield.[16] Women involved in the revolution were just as laden if not more so than men, carrying food, cooking supplies, and bedding.[16] Many soldaderas took their children with them, often because their husband had joined or been conscripted into the army. In 1914, a count of Pancho Villa’s forces included 4,557 male soldiers, 1,256 soldaderas, and 554 children many of whom were babies or toddlers strapped to their mother’s backs.[16] Many women picked up arms and joined in combat alongside men, often when a male comrade, their husband or brother had fallen.[16]

There were also many cases of women who fought in the revolution disguised as men, however most returned to female identities once the conflict had ended.[16] The lasting impacts of the revolution have proved mixed at best. The revolution promised reforms and greater rights for women to one extent or another, but failed to live up to its promises. Thousands of women fought in the battles and provided necessary services to the armies, however their contributions have largely been forgotten and viewed as merely supportive.[16]

There had been agitation for women's suffrage in Mexico in the late nineteenth century, and both Francisco Madero and Venustiano Carranza were sympathetic to women's issues, both having female private secretaries who influenced their thinking on the matter.[18] Carranza's secretary Hermila Galindo was an important feminist activist, who in collaboration with others founded a feminist magazine La Mujer Moderna that folded in 1919, but until then advocated for women's rights. Mexican feminist Andrea Villarreal was active agitating against the Díaz regime in the Mexican Liberal Party and was involved with La Mujer Moderna, until it ceased publication. She was known as the "Mexican Joan of Arc" and was a woman represented in U.S. artist Judy Chicago's dinner party.[19]

Carranza made changes in family and marital law with long-lasting consequences. In December 1914, he issued a decree that allowed for divorce under certain circumstances. His initial decree was then expanded when he became president in 1916, which in addition to divorce "gave women the right to alimony and to the management of property, and other similar rights."[20]

With the victory of the Constitutionalist faction in the Revolution, a new constitution was drafted in 1917. It was an advanced social document on many grounds, enshrining rights of labor, empowering the state to expropriate natural resources, and expanding the role of the secular state, but it did not grant women the right to vote, since they were still not considered citizens.[21]

During the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–40), legislation to give women the right to vote was passed, but not implemented. He had campaigned on a "promise to reform the constitution to grant equal rights."[22] Women did not achieve the right to vote until 1953.

Women in the Professions

Politics

|thumb|right|Olga Sanchez Cordero, Minister of the Interior]]

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

|thumb|left|200px|Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo a Mexican politician and scientist who jointly received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007 as a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.]]

Although women comprise half of the Mexican population, they are generally absent from the highest ranks of political power. They did not achieve the vote nationally until 1953. However, President Porfirio Díaz married Carmen Romero Rubio the young daughter of one of his cabinet ministers, Manuel Romero Rubio; she was an influential First Lady of Mexico during his long presidency, 1881–1911. A few subsequent First Ladies took more visible roles in politics. The wife of President Vicente Fox (2000-2006), Marta Sahagún was an active member of the National Action Party[23] and became the wife of Fox after she had served as his spokesperson. Sahagún was criticized for her political ambitions, and she has stated that she will no longer pursue them. She was seen as undermining Fox's presidency.[24] A political landmark in Mexico was the election of feminist and socialist Rosa Torre González to the city council of Mérida, Yucatán in 1922, becoming the first woman elected to office in Mexico. The state accorded women the vote shortly after the Mexican Revolution.[25] During the presidency of Ernesto Zedillo (1994-2000), Rosario Green served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs, briefly served as Secretary General of the Institutional Revolutionary Party,[26] and as a Mexican senator. Amalia García became the fifth woman to serve as governor of a Mexican state on September 12, 2004 (Zacatecas 2004–2010). Earlier women governors were Griselda Álvarez (Colima, 1979–1985), Beatriz Paredes (Tlaxcala, 1987–1992), Dulce María Sauri (Yucatán, 1991–1994), Rosario Robles Berlanga (Distrito Federal, 1999–2000). From 1989 to 2013, the head of the Mexican teachers' trade union was Elba Esther Gordillo, considered at one point the most powerful woman in Mexican politics. She was the first and so far only head of the largest union in Latin America; in 2013 she was arrested for corruption and was named by Forbes Magazine as one of the 10 most corrupt Mexicans of 2013.[27] The Minister of Education in the government of Felipe Calderón was Josefina Vázquez Mota, so far the first and only woman to hold the position. She went on to become the presidential candidate for the National Action Party[23] in 2018. First Lady Margarita Zavala wife of the former President of Mexico Felipe Calderón also ran as an independent candidate for the presidency of Mexico between October 12, 2017, and May 16, 2018.

On the left, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador appointed an equal number of women and men to his cabinet when he took office in 2018. These include Olga Sánchez Cordero as Secretary of the Interior, the first woman to hold the high office. Other women in his cabinet are Graciela Márquez Colín, Secretary of the Economy; Luisa María Alcalde Luján, Secretary of Labor and Social Welfare; Irma Eréndira Sandoval, Secretary of Public Administration; Alejandra Frausto Guerrero, Secretary of Culture; Rocío Nahle García, Secretary of Energy; María Luisa Albores González, Secretary of Social Development; and Josefa González Blanco Ortiz Mena, Secretary of the Environment and Natural Resources.[28] Claudia Sheinbaum was elected mayor of Mexico City as a candidate for the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) party, the first woman to hold the post;[29] it has been previously held by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas and López Obrador.

.jpg.webp)

Human rights activists

A number of women have been active in various kinds of human rights movements in Mexico.

Women intellectuals, journalists, and writers

Eulalia Guzmán participated in the Mexican Revolution and then taught in a rural primary school and was the first woman archeologist in Mexico. Her identification of human bones as those of Aztec emperor Cuauhtémoc brought her to public attention. Rosario Castellanos was a distinguished twentieth-century feminist novelist, poet, and author of other works, a number of which have been translated to English.[30] At the time of her death at 49, she was Mexican ambassador to Israel. Novelist Laura Esquivel (Like Water for Chocolate) has served in the Mexican Chamber of Deputies for the Morena Party. Other women writers have distinguished themselves nationally and internationally in the modern era, including Anita Brenner,[31] and Guadalupe Loaeza.[32] The most famous woman writer and intellectual was seventeenth-century nun, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. "Today, Sor Juana stands as a national icon of Mexican identity, and her image appears on Mexican currency. She came to new prominence in the late 20th century with the rise of feminism and women's writing, ... credited as the first published feminist of the New World."[33] A number of women have become distinguished intellectuals in modern Mexico, especially Elena Poniatowska, whose reportage on the Tlatelolco Massacre of 1968 and the 1995 Mexico City earthquake have been important. Historian Virginia Guedea has specialized in the history of independence-era Mexico.

Many Mexican journalists have been murdered since the 1980s, including a number of Mexican women. In 1986, Norma Alicia Moreno Figueroa was the first woman journalist identified as a murder victim of the Mexican drug war.[34] Broadcast crime reporter Dolores Guadalupe García Escamilla was murdered in 2005.[35] Yolanda Figueroa was murdered in the drug war, along with her journalist husband, Fernando Balderas Sánchez, and children in 1996.[36] In 2009, Michoacan journalist María Esther Aguilar Cansimbe disappeared.[37] Former TV journalist at Televisa, María Isabella Cordero was murdered in Chihuahua in 2010.[38] In Veracruz in 2011, crime reporter Yolanda Ordaz de la Cruz was killed.[39] Marisol Macías was murdered in Nuevo Laredo by the Los Zetas in 2011.[40]

Women in the arts

There is a long list of Mexican women in the arts. Probably the most famous woman artist in Mexican history is painter Frida Kahlo, daughter of a prominent photographer Guillermo Kahlo and wife of muralist Diego Rivera. Frida Kahlo was known for her famous self portraits.

In the circle of Mexican muralists was painter María Izquierdo, whose work is often examined with her contemporary Kahlo.[41][42] Ángela Gurría was the first woman elected to the Academia de Artes. Graciela Iturbide is one of a number of Mexican women photographers who have gained recognition. Amalia Hernández founded the Ballet Folklórico de México, which continues to perform regularly at the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City. Google celebrated Hernández on the anniversary of her 100th birthday.[43]

A number of Mexican actresses have reached prominence outside Mexico, including Salma Hayek[44] and María Félix.[45] Yalitza Aparicio, an indigenous woman from Oaxaca, starred in Alfonso Cuarón's 2018 film Roma.[46]

Architecture

Mexican women have made significant advancements in the field of architecture.

The first prominent woman architect in Mexico was Ruth Rivera Marin (1927-1969). She was the daughter of Diego Rivera and Guadalupe Marín Preciado. Rivera was the first woman to study architecture at the College of Engineering and Architecture of the National Polytechnic Institute. She focused primarily on teaching architectural theory and practice and was the head of the Architecture Department at the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes from 1959 to 1969. After her father's death, she worked with Mexican architects Juan O'Gorman and Heriberto Pagelson to complete the Anahuacalli Museum in Coyoacán.

In the early twenty-first century, Mexico has had several important women architects at the forefront of architectural innovation. Sustainability, balance, and integration with nature have been important motifs in their works. Beatriz Peschard Mijares' ultra-luxury modernist projects balance minimalist structures with their surrounding landscapes. This aim of functionalist balance is rooted in Peschard's own personal struggles balancing “family life, being a mother, and her work” as an architect.[47] A major proponent of experimentation in Mexican architecture, Peschard stated in 2017 that it's important to “invent new things, not to copy either the Mexican or the foreigner... [but to] search our history and combine what we find with technological and technical advances to create something personal and innovative.”[47]

Another prominent 21st-century Mexico City architect, Tatiana Bilbao (1972) has designed several buildings which merge geometry with nature. Her practice has largely focused on sustainable design and social housing. Bilbao was born in Mexico City into a family of architects, and she studied architecture at the Universidad Iberoamericana. Bilbao is a strong advocate of architectural social justice, and many of her projects have sought to create low-cost housing to address Mexico's affordable housing crisis.[48]

Ruth Rivera Marin: Anahuacalli Museum (1964)

Ruth Rivera Marin: Anahuacalli Museum (1964) Tatiana Bilbao: Exhibition Room in Jinhua Architecture Park (2004)

Tatiana Bilbao: Exhibition Room in Jinhua Architecture Park (2004)

Contemporary issues

Labor rights

Many women in the workforce do not have legal protections, especially domestic workers. In 2019, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador signed into law protections and benefits for domestic workers, including access to health care and limits on hours of work. The legislation comes after years of activism, including that by Marcelina Bautista, who founded SINACTRAHO, Mexico's first domestic workers union, in 2015. Awareness of the issue got a boost from the 2018 film Roma by Alfonso Cuarón, whose main character is an indigenous female domestic servant. Enforcement of the legislation will be a challenge, since costs to employers will significantly increase.[49]

Violence against women

As of 2012, Mexico has the 16th highest rate of homicides committed against women in the world.[50] In the first 4 months of 2020 987 women and girls were murdered.[51] Approximately 10 women are killed every day in Mexico, and the rate of femicide has doubled in the last 5 years.[50]

According to the 2013 Human Rights Watch, many women do not seek out legal redress after being victims of domestic violence and sexual assault because "the severity of punishments for some sexual offenses are contingent on the "chastity" of the victim and "those who do report them are generally met with suspicion, apathy, and disrespect."[52]

According to a 1997 study by Kaja Finkler, domestic abuse is more prevalent in Mexican society as women are dependent on their spouses for subsistence and self esteem, caused by the embedded societal ideology of romantic love, family structure, and residential arrangements.[53]

Mexican women are at risk for HIV infection because they often are unable to negotiate condom use. According to published research by Olivarrieta and Sotelo (1996) and others, the prevalence of domestic violence against women in Mexican marital relationships varies at between 30 and 60 percent of relationships. In this context, requesting condom use with a stable partner is perceived as a sign of infidelity and asking to use a condom can result in domestic violence.[54]

In Mexico City, the area of Iztapalapa has the highest rates of rape, violence against women, and domestic violence in the capital.[55]

Gender violence is more prevalent in regions along the Mexico-US border and in areas of high drug trading activity and drug violence.[56] The phenomenon of the female homicides in Ciudad Juárez involves the violent deaths of hundreds of women and girls since 1993 in the northern Mexican region of Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, a border city across the Rio Grande from the U.S. city of El Paso, Texas. As of February 2005, the number of murdered women in Ciudad Juarez since 1993 is estimated to be more than 370.[57] The civic organization Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa A.C. was founded by Norma Andrade in Ciudad Juárez. Her daughter was one of the rape and murder victims. Andrade was subsequently attacked twice by assailants.[58] In November 2019, Mexico vowed to stop gender-based violence as new statistics showed killings of women rose more than 10% in 2018.[59]

Women in the Mexican Drug War (2006–present) have been raped,[60][61] tortured,[62][63] and murdered in the conflict.[64][65][66][67][68] They have also been victims of sex trafficking in Mexico.[69][70][71][72][73][74]

Contraception

.jpg.webp)

Even as late as the 1960s, the use of contraceptives was prohibited by civil law, but there were private clinics where elite women could access care.[75][76][77]

Surging birthrates in Mexico in the 1960s and 70s became a political issue, particularly as agriculture was less productive and Mexico was no longer self-sufficient in food. As Mexico became more urban and industrialized, the government formulated and implemented family planning policies in the 1970s and 80s that aimed at educating Mexicans about the advantages of controlling fertility.[78] A key component of the educational campaign was the creation of telenovelas (soap operas) that conveyed the government's message about the virtues of family planning. Mexico pioneered the use of soap operas to shape public attitudes on sensitive issues in a format both accessible and enjoyable to a wide range of viewers.[79] Mexico's success in reducing the increase of its population has been the subject of scholarly study.[80][81]

One scholar, the Stanford University historian Ana Raquel Minion, has attributed at least part of Mexico's success to forced sterilization programs. In her 2018 text Undocumented Lives, she writes:

"After the new Ley General of 1974 passed, some medical authorities in public health care institutions responded to the growing pressures to lower birth rates by forcibly sterilizing working-class women immediately after they delivered via cesarean section. Because most of these cases went undetected and undenounced, their exact number is unknown. However, a governmental study performed in 1987 found staggering results. Ten percent of the women in the national sample claimed to have been sterilized without having been asked; 25 percent affirmed they were not informed that sterilization was an irreversible method of birth control or that other options existed; and 70 percent declared that they had been sterilized immediately after giving brith or having an abortion."[82]

Contraception is still a big issue for Mexican women with a population of 107 million. It is the second most populous nation in Latin America. The population trend is even expected to grow in size in a little over thirty years. With a population that keeps increasing it was the first nation in 1973 to establish a family planning program. It is called MEXFAM (The Mexican Family Planning Association); the program has been recorded to have decreased Mexican households from 7.2 children to 2.4 in 1999.[83]

Contraceptive use in rural areas is still far lower than that of urban areas. Approximately 25% of Mexican women live in rural areas, and of that, only 44% of those use birth control, and their fertility rate, 4.7%, is almost twice that of urban women.”[83] Mexico was even able to incorporate a sexual education program in the schools to educate on contraception, but with many young girls living in rural areas, they are usually not able to attend.

Emergency Contraception in Mexico Since the introduction of Emergency Contraception (EC) into the Mexican family planning guidelines in 2004, knowledge and usage of EC has been rapidly growing (Han, 2017). The past years, EC has been available as an over-the-counter product without age restriction and also free of charge in the national health system. So far, there are 13 different kinds of pills that can be purchased without prescription (LNG-EC products) and one where a prescription is needed (UPA-EC product) (ICEC, 2012). The rapid growth in education and use of Emergency Contraception, can be seen in a study conducted by Leo Han et. Al., comparing data from the ENADID survey from 2006, 2009, and 2014. EC knowledge among women has accordingly inclined from 62% in 2006, 79% in 2009 to 83% in 2014, and the use EC among women who have generally used contraception rose from 3% (2006), to 11% (2009) to 14% (2014) (Han, 2017). However, certain disparities in the increased knowledge have been identified. Reproductive health experts have concluded, that “stigma, gender, relationships and ethnicity may all play a role in a woman´s experience in receiving birth control” (Rafanelli, 2022), leading to less, or even denied access to EC. Lower wealth and education, rural living and indigenous status on access and knowledge are associated with less possibilities of contact to EC resources, denying women in certain living situations the chances to break out of sometimes repressive gender roles and with less bodily autonomy. So while the rapid growth in knowledge and use of Emergency Contraception in Mexico can be seen as a successful step in women's empowerment, a lot of steps still must be taken in order to include Mexican women in all kinds of living situations.

Sexuality

There are still persisting inequalities between levels of sexual experience between females and males. In national survey of Mexican youth published in 2000, 22% of men and 11% of women of the age 16 had admitted to having experienced sexual intercourse.[84] However, these rates for both men and women remain fairly low due to the cultural perception that it is inappropriate to engage in intercourse before marriage. This shared cultural belief stems from the traditional teachings of the Catholic Church which has had great influence over Latin American cultures.[85]

Perceptions of beauty

Mexican women have participated in international beauty competitions.

Activism

.jpg.webp)

In 2020, activists called for a one-day strike by women on March 9, the day after International Women's Day (March 8). The strike has been called "A Day Without Women," to emphasize women's importance in Mexico. At the March 8th demonstration in Mexico City, there was a crowd estimated at 80,000 people. There was a widespread response to the strike the next day as well, with both events reported in the international press.[86][87][88] The strike is part of a new wave of feminism in Mexico.[89] President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has been called tone-deaf on the issue, a source of feminist criticism.[90]

Official logo of the government of Mexico

The original logo of the Government of Mexico, in force since Andrés Manuel López Obrador assumed the Presidency on December 1, 2018, caused controversy by showing five men protagonists of the history of Mexico and no woman. In the image the characters appear, that López Obrador has qualified as his references on various occasions. These are Benito Juárez (1806-1872) president who faced the French and American invasion; Francisco Ignacio Madero (1873-1913), forerunner of the Mexican Revolution, and Lázaro Cárdenas (1895-1970), president who nationalized oil. Also Miguel Hidalgo (1753-1811) new Hispanic priest who starred the Grito de Dolores with which the War of Independence began, and José María Morelos (1765-1815), one of the main leaders of the independence struggle.

Female version

A new official logo featuring prominent women in the country's history on the occasion of the commemoration of International Women's Day. In the green and gold logo, used in official events and in government social networks five celebrities appear on the motto "Women transforming Mexico. March, women's month." In the center of the image appears holding a Mexican flag Leona Vicario (1789-1842), one of the most outstanding figures of the Mexican War of Independence (1810-1821) who served as an informant for the insurgents from Mexico City then capital of the vice-royalty. To her left, it is also drawn Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez (1768-1829), known as "la Corregidora" who played a fundamental role in the conspiracy that gave rise to the beginning of the independence movement from the state of Querétaro. The nun and neo-Hispanic writer sister sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648-1695), one of the main exponents of the Golden Age of literature in Spanish thanks to her lyrical and dramatic work, both religious and profane stars in the far left of the image. On the opposite side, the revolutionary Carmen Serdán (1875-1948), is drawn, who strongly supported from the city of Puebla to Francisco Ignacio Madero in his proclamation against the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, which was finally overthrown in 1911. On her side is located Elvia Carrillo Puerto (1878-1968), who was a feminist leader who fought for the right to vote of women in Mexico, which was achieved in 1953 and that she became one of the first women to hold office elected when elected as a deputy in the state congress of Yucatan.

See also

References

- ↑ "Mexican women - then and now - International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine". www.internationalviewpoint.org. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ Valdés, Margarita M. (1995). Nussbaum M. e Glover J. (ed.). Inequality in capabilities between men and women in Mexico. pp. 426–433.

- ↑ "Femicide and Impunity in Mexico: A context of structural and generalized violence" (PDF). Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Socolow, S. M. (2000). The women of colonial Latin America. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- 1 2 Kellogg, Susan. (1986). Aztec Inheritance in Sixteenth-Century Mexico City: Colonial Patterns, Prehispanic Influences. Duke University Press.

- 1 2 Alves, A. A. (1996). Brutality and benevolence: Human ethology, culture, and the birth of Mexico. Greenwood Press, Westwood, Conn. p. 71.

- ↑ Alves, A. A. (1996). Brutality and benevolence: Human ethology, culture, and the birth of Mexico. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. Pg 72

- ↑ Tuñón, J. (1999). Women in Mexico: A past unveiled. Austin: University of Texas Press, Institute of Latin American Studies, p 16.

- ↑ Alves, A. A. (1996). Brutality and benevolence: Human ethology, culture, and the birth of Mexico. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press.74

- ↑ Ilarione, ., Miller, R. R., & Orr, W. J. (2000). Daily life in colonial Mexico: The journey of Friar Ilarione da Bergamo, 1761-1768. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, p 92.

- ↑ Martínez, M. E. (2008). Genealogical fictions: Limpieza de sangre, religion, and gender in colonial Mexico. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, p 174

- ↑ Socolow, S. M. (2000). The women of colonial Latin America. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, p 61

- ↑ Socolow, S. M. (2000). The women of colonial Latin America. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, p 166

- ↑ Silvia Arrom, La Güera Rodríguez: The Life and Legends of a Mexican Independence Heroine. Austin: University of Texas Press 2021

- ↑ quoted in Miller, Francesca. "Feminism and Feminist Organizations" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 2, p. 551. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 O’Connor, Erin E. (2014). Mothers Making Latin America. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- ↑ Miller, "Feminism and Feminist Organizations", p. 550

- ↑ Wade M. Morton, Woman Suffrage in Mexico. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1962, p. 2-3.

- ↑ "Brooklyn Museum: Andres Villareal". www.brooklynmuseum.org. Retrieved 2018-02-19.

- ↑ Morton, Woman Suffrage in Mexico, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Miller, "Feminism and Feminist Organizations" pp. 550-51.

- ↑ Miller, "Feminism and Feminist Organizations" p. 552

- 1 2 "National Action Party | History & Ideology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ↑ EDT, Scott C. Johnson On 7/18/04 at 8:00 PM (2004-07-18). "WORST LADY?". Newsweek. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Asunción Lavrin (1978). Latin American Women: Historical Perspectives. Westport: Greenwood Press 1978.

- ↑ "Institutional Revolutionary Party | History & Ideology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ↑ Estevez, Dolia. "The 10 Most Corrupt Mexicans Of 2013". Forbes. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ "AMLO announced his cabinet in December; this is who they are". Mexico News Daily. 2018-07-03. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ "Meet Mexico City's First Elected Female Mayor". NPR.org. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ A Rosario Castellanos Reader: An Anthology of Her Poetry, Short Fiction, Essays and Drama. Austin University of Texas Press 2010.

- ↑ John A. Britton, "Anita Brenner" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, p. 467. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996

- ↑ "Guadalupe Loaeza". 2011-03-05. Archived from the original on 2011-03-05. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ "Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz". Biography. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ "54 periodistas asesinados y dos desaparecidos. Por Teodoro Rentería Arróyave - CUBAPERIODISTAS-". 2012-03-08. Archived from the original on 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ Avenue, Committee to Protect Journalists 330 7th; York, 11th Floor New; Ny 10001. "Dolores Guadalupe García Escamilla". cpj.org. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "CNN - Grisly murder points to drugs, powerful figures in Mexico - Dec. 6, 1996". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ Avenue, Committee to Protect Journalists 330 7th; York, 11th Floor New; Ny 10001 (20 November 2009). "Mexican crime reporter vanishes in western Michoacán". cpj.org. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Latin American Herald Tribune - Former Televisa Reporter Killed in Mexico". www.laht.com. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ "Mexico crime reporter found dead". 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ Avenue, Committee to Protect Journalists 330 7th; York, 11th Floor New; Ny 10001. "Maria Elizabeth Macías Castro". cpj.org. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Deffebach, Nancy. María Izquierdo and Frida Kahlo: Challenging Visions in Modern Mexican Art. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015.

- ↑ Tarver, Gina. "Issues of Otherness and Identity in the Works of Izquierdo, Kahlo, Artaud, and Breton". The Latin American Institute: University of New Mexico, April 1996, vol. 27.

- ↑ "All you need to know about Amalia Hernandez, who Google is celebrating". The Independent. 2017-09-18. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ "Salma Hayek | Biography, Movies, TV Shows, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ "María Félix | Mexican actress". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ Sippell, Margeaux (2018-12-06). "First-Time Actress Yalitza Aparicio on How She Found 'Roma'". Variety. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- 1 2 Romero, Graciela (22 July 2017). "Inventar desde la experiencia: Beatriz Peschard". México Design. Grupo México Design. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ↑ "Tatiana Bilbao "urgent" housing Mexico's poorest inhabitants". Dezeen. 2015-10-06. Archived from the original on 2019-11-12. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ↑ Villegas, Paulina (2019-05-14). "Mexico's Congress Votes to Expand Domestic Workers' Labor Rights". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- 1 2 "Femicides in Mexico: Impunity and Protests". www.csis.org. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ↑ Gallon, Natalie (16 July 2020). "Women are being killed in Mexico at record rates, but the president says most emergency calls are 'false'". CNN.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch (31 January 2013). World Report 2013: Mexico. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ↑ Finkler, Kaja (1997). "Gender, domestic violence and sickness in Mexico". Social Science & Medicine. 45 (8): 1147–1160. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00023-3. PMID 9381229.

- ↑

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Health Profile: Mexico" Archived 2009-09-10 at the Wayback Machine. United States Agency for International Development (June 2008). Accessed September 7, 2008.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Health Profile: Mexico" Archived 2009-09-10 at the Wayback Machine. United States Agency for International Development (June 2008). Accessed September 7, 2008. - ↑ Ríos, Fernando (October 8, 2010). "Tiene Iztapalapa el más alto índice de violencia hacia las mujeres" [Iztapalapa has the highest rate of violence against women]. El Sol de México (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- ↑ Wright, Melissa W. (March 2011). "Necropolitics, Narcopolitics, and Femicide: Gendered Violence on the Mexico-U.S. Border". Signs. 36 (3): 707–731. doi:10.1086/657496. JSTOR 10.1086/657496. PMID 21919274. S2CID 23461864.

- ↑ "Mexico: Justice fails in Ciudad Juarez and the city of Chihuahua". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ↑ P, Eesha; Ago, It • 7 Years. "Human rights activist Norma Andrade shot in Juarez". Feministing. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Mexico commits to 'zero tolerance' of violence against women amid rise in killings". Reuters. 2019-11-25. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ "Mexico's Narco-Insurgency". Time. January 25, 2008.

- ↑ "More than 11,000 migrants abducted in Mexico". BBC News. February 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Drug Killings Haunt Mexican Schoolchildren". The New York Times. October 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Mexican police find 12 bodies in Cancun". Reuters. June 18, 2010.

- ↑ "Drug traffickers suspected in murders of 154 women". Fox 5 Morning News. January 2, 2020.

- ↑ "Cartel turf war behind Juarez massacre, official says". CNN. February 2, 2010.

- ↑ "72 Bodies Found at Ranch: Mexico Massacre Survivor Describes Grisly Scene". CBS News. August 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Mass graves in Mexico reveal new levels of savagery". The Washington Post. April 24, 2011.

- ↑ "Mexican newspaper editor Maria Macias found decapitated". BBC News. September 25, 2011.

- ↑ "How a Mexican family became sex traffickers". Thomson Reuters Foundation. November 30, 2017.

- ↑ "The Mexican Drug Cartels' Other Business: Sex Trafficking". Time. July 31, 2013.

- ↑ "Tenancingo: the small town at the dark heart of Mexico's sex-slave trade". The Guardian. April 4, 2015.

- ↑ "DOJ: Mexican Sex Trafficking Organization Uses Southern Border to Smuggle Victims". People's Pundit Daily. January 7, 2019.

- ↑ "Human trafficking survivors find hope in Mexico City". Deseret News. July 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Human trafficking survivor: I was raped 43,200 times". CNN. September 20, 2017.

- ↑ Gabriela Soto Laveaga, "'Let's become fewer': Soap operas, contraception, and nationalizing the Mexican family in an overpopulated world." Sexuality Research and Social Policy September 2007, vol. 4 no. 3, p. 23.

- ↑ G. Cabrera, "Demographic dynamics and development: The role of population policy in Mexico." in The New Politics of Population: conflict and consensus in family planning, Population and Development Review 20 (suppl.) 105-120.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Barocio, R.; et al. (1980). "Fertility and family planning in Mexico". International Family Planning Perspectives. 6 (1): 2–9. doi:10.2307/2947963. JSTOR 2947963.

- ↑ Soto Laveaga, “Let’s Become Fewer” p. 19

- ↑ Miguel Sabido, Towards the social use of soap operas. Mexico City: Institute for Communication Research 1981.

- ↑ Soto Laveaga, “Let’s become fewer”

- ↑ F. Turner, Responsible parenthood: The politics of Mexico’s new population policies. Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research 1974.

- ↑ Minian, Ana Raquel (March 18, 2018). Undocumented Lives: The Untold Story of Mexican Migration (1 ed.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780674737037. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- 1 2 Birth Control & Mexico. (n.d.). .. Retrieved April 20, 2014, from http://www.d.umn.edu/~lars1521/BC&Mexico.htm Archived 2017-12-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ MEXFAM. 2000. Encuesta genre joven.Fundación Mexicana para la Paneación Familiar. México.

- ↑ Welti, Carlos (2002). Adolescents in Latin America: Facing the Future with Skepticism. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 289–290. ISBN 9780521006057.

- ↑ New York Times, "Mexican Women Strike and Protest". accessed 10 March 2020

- ↑ "Mexican Women Stay Home to Protest Femicides in a Day Without Us", National Public Radio accessed 10 March 2020

- ↑ "Mexico: A Day Without Women" New York Times accessed 2 February 2020

- ↑ The Economist, "Mexico's New Feminist Wave", accessed 7 March 2020.

- ↑ "Antiviolence in Mexico: "Despiccable women seethe over Mexican leader's wobbly response to violence" Reuters. access 6 March 2020

Further reading

- Alonso, Ana Maria. Thread of Blood: Colonialism, Revolution, and Gender on Mexico's Northern Frontier. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 1995.

- Arrom, Silvia. The Women of Mexico City, 1790-1857. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1985.

- Arrom, Silvia. Volunteering for a Cause: Gender, Faith, and Charity from the Reform to the Revolution. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2016.

- Bartra, Eli. "Women and Portraiture in Mexico". In "Mexican Photography." Special Issue, History of Photography 20, no. 3 (1996)220-25.

- Bliss, Katherine Elaine. Compromised Positions: Prostitution, Public Health, and Gender Politics in Revolutionary Mexico City. University Park: Penn State Press, 2001.

- Blum, Ann S. Domestic Economies: Family, Work, and Welfare in Mexico City, 1884-1943. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 2009.

- Boyer, Richard. "Women, La Mala Vida, and the Politics of Marriage," in Sexuality and Marriage in Colonial Latin America, Asunción Lavrin, ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1989.

- Blough, William J (1972). "Political attitudes of Mexican women: Support for the political system among a newly enfranchised group". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 14 (2): 201–224. doi:10.2307/174713. JSTOR 174713.

- Bruhn, Kathleen. "Social spending and political support: The" lessons" of the National Solidarity Program in Mexico." Comparative Politics (1996): 151-177.

- Buck, Sarah A. "The Meaning of Women's Vote in Mexico, 1917-1953" in Mitchell and Schell, The Women's Revolution in Mexico, 1953 pp. 73–98.

- Castillo, Debra A. Easy Women: Sex and Gender in Modern Mexican Fiction. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 1998.

- Chasteen-López, Francie. "Cheaper than Machines: Women in Agriculture in Porfirian Oaxaca." in Creating Spaces, Shaping Transitions: Women of the Mexican Countryside, 1850-1990, ed. Mary Kay Vaughan and Heather Fowler-Salamini. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 1994, pp. 27–50.

- Chowning, Margaret. Rebellious Nuns: The Troubled History of a Mexican Convent, 1752-1863. New York: Oxford University Press 2005.

- Cortina, Regina. "Gender and Power in the Teacher's Union of Mexico." Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 6. no. 2 (Summer 1990): 241–62.

- Deans-Smith, Susan. “The Working Poor and the Eighteenth-Century Colonial State: Gender, Public Order, and Work Discipline.” In Rituals of Rule, Rituals of Resistance: Public Celebrations and Popular Culture in Mexico, edited by William H. Beezley, Cheryl English Martin, and William E. French. Wilmington, Del.: SR Books, 1994.

- Fernández Aceves, María Teresa. “Guadalajaran Women and the Construction of National Identity.” In The Eagle and the Virgin: Nation and Cultural Revolution in Mexico, 1920-1940, edited by Mary Kay Vaughan and Stephen E. Lewis. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2006.

- Fisher, Lillian Estelle. "The Influence of the Present Mexican Revolution upon the Status of Mexican Women," Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 22, No. 1 (Feb. 1942), pp. 211–228.

- Fowler-Salamini, Heather. Working Women, Entrepreneurs, and the Mexican Revolution: The Coffee Culture of Córdoba, Veracruz. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 2013.

- Fowler-Salamini, Heather and Mary Kay Vaughn, eds. Women of the Mexican Countryside, 1850-1990. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 1994.

- Franco, Jean. Plotting Women: Gender and Representation in Mexico. New York: Columbia University Press 1989.

- French, William E. "Prostitutes and Guardian Angels: Women, Work and the Family in Porfirian Mexico," Hispanic American Historical Review 72 (November 1992).

- García Quintanilla, Alejandra. "Women's Status and Occupation, 1821-1910," in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 2, pp. 1622–1626. Chicago: Fitzroy and Dearbon 1997.

- Gonzalbo, Pilar. Las Mujeres en la Nueva España: Educación y la vida cotidiana. Mexico City: Colegio de México 1987.

- Gosner, Kevin and Deborah E. Kanter, ed. Women, Power, and Resistance in Colonial Mesoamerica. Ethnohistory 45 (1995).

- Gutiérrez, Ramón A. When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico, 1500-1846. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1991.

- Healy, Teresa. Gendered Struggles Against Globalisation in Mexico. Burlington VT: Ashgate 2008.

- Hershfield, Joanne. Imagining the Chica Moderna: Women, Nation, and Visual Culture in Mexico, 1917-1936. Durham: Duke University Press 2008.

- Herrick, Jane (1957). "Periodicals for Women in Mexico during the Nineteenth Century". The Americas. 14 (2): 135–44. doi:10.2307/979346. JSTOR 979346. S2CID 143883806.

- Jaffary, Nora E. Reproduction and Its Discontents in Mexico: Childbirth and Contraception from 1750 to 1905. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 2016. ISBN 978-1-4696-2940-7

- Johnson, Lyman and Sonya Lipsett-Rivera, eds. The Faces of Honor: Sex, Shame, and Violence in Colonial Latin America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1998.

- Klein, Cecilia. "Women's Status and Occupation: Mesoamerica," in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 2 pp. 1609–1615. Chicago: Fitzroy and Dearborn 1997.

- Lavrin, Asunción, ed. Sexuality and Marriage in Colonial Latin America. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1989.

- Lavrin, Asunción. "In Search of the Colonial Woman in Mexico: The Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries." In Latin American Women: Historical Perspectives. Westport CT: Greenwood Press 1978.

- Lipsett-Rivera, Sonya. "Women's Status and Occupation: Spanish Women in New Spain," in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 2. pp. 1619–1621. Chicago: Fitzroy and Dearborn 1997.

- Lipsett-Rivera, Sonya. Gender and the Negotiation of Daily Life in Mexico, 1950-1856. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 2012.

- López, Rick (2002). "The India Bonita Contest of 1921 and the Ethnicization of Mexican National Culture". Hispanic American Historical Review. 82 (2): 291–328. doi:10.1215/00182168-82-2-291. S2CID 144334794.

- Macías, Ana. Against All Odds: The Feminist Movement in Mexico to 1940. Westport CT: Greenwood 1982.

- Martínez, Maria Elena. Genealogical fictions: Limpieza de sangre, religion, and gender in colonial Mexico. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press 2008.

- Melero, Pilar. Mythological Constructs of Mexican Femininity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2015.

- Mitchell, Stephanie. “Por la liberación de la mujer: Women and the Anti-Alcohol Campaign.” In The Women’s Revolution in Mexico, 1910-1953. Edited by Stephanie Mitchell and Patience A. Schell. 173–185. Wilmington, DE: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007

- Mitchell, Stephanie and Patience a. Schell, eds. The Women’s Revolution in Mexico, 1910-1953. Wilmington, DE: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007

- Morton, Ward M. Woman Suffrage in Mexico. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1962.

- Muriel, Josefina. Cultura feminina novohispana. 2nd edition. Mexico City: UNAM 1994.

- Muriel, Josefina. Los Recogimientos de mujeres: Respuesta a una problemática social novohispana. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 1974.

- Olcott, Jocelyn. Revolutionary Women in Postrevolutionary Mexico. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2005.

- Olcott, Jocelyn, Mary Kay Vaughan, and Gabriela Cano, eds. Sex in Revolution: Gender, Politics, and Power in Modern Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press 2006.

- Overmyer-Velázquez, Mark. "Portraits of a Lady: Visions of Modernity in Porfirian Oaxaca, Mexico." Mexican Studies/ Estudios Mexicanos 23, no. 1 (2007) 63–100.

- Pierce, Gretchen. “Fighting Bacteria, the Bible, and the Bottle: Projects to Create New Men, Women, and Children, 1910-1940.” In A Companion to Mexican History and Culture. Edited by William H. Beezley. 505–517. London: Wiley-Blackwell Press, 2011.

- Porter, Susie S. From Angel to Office Worker: Middle-Class Identity and Female Consciousness in Mexico, 1890-1950. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 2018.

- Porter, Susie S. Working Women in Mexico City: Material Conditions and Public Discourses, 1879-1931. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 2003.

- Ramos Escandón, Carmen. "Women's Movements, Feminism and Mexican Politics." In The Women's Movement in Latin America: Participation and Democracy. Jane S. Jaquette, 199–221.boulder: Westview Press 1994.

- Rashkin, Elissa J. Women Filmmakers in Mexico" The Country of Which We Dream. Austin: University of Texas Press 2001.

- Salas, Elizabeth. Soldaderas in the Mexican Military. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press 1990.

- Sanders, Nichole. Gender and Welfare in Mexico: The Consolidation of a Postrevolutionary State. University Park: Penn State University Press 2011.

- Schroeder, Susan. "Women's Status and Occupation: Indian Women in New Spain," in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 2. pp. 1615–1618. Chicago: Fitzroy and Dearborn 1997.

- Schroeder, Susan, Stephanie Wood, and Robert Haskett, eds. Indian Women of Early Mexico. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1997.

- Seed, Patricia. To Love, Honor, and Obey in Colonial Mexico: Conflicts over Marriage Choice, 1574-1821. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1988.

- Singer, Elyse Ona. Lawful Sins: Abortion Rights and Reproductive Governance in Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2022. ISBN 978-1-5036-3147-2

- Sloan, Kathryn A. Runaway Daughters: Seduction, Elopement, and Honor in Nineteenth-Century Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2008.

- Smith, Stephanie L. Gender and the Mexican Revolution: Yucatán women and the Realities of Patriarchy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 2009.

- Socolow, Susan. M. The women of colonial Latin America. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press 2000

- Soto, Shirlene. Emergence of the Modern Mexican Woman: Her Participation in Revolution and Struggle for Equality 1910-1940. Denver, Colorado: Arden Press, INC. 1990.

- Stepan, Nancy Leys. “The Hour of Eugenics:” Race, Gender, and Nation in Latin America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991.

- Stephen, Lynn. Zapotec Women. Austin: University of Texas Press 1991.

- Stern, Alexandra Minna. "Responsible Mothers and Normal Children: Eugenics, Nationalism, and Welfare in Post-revolutionary Mexico, 1920-1940." Journal of Historical Sociology vol. 12, no. 4 (December 1999) pp. 369–397.

- Stern, Steve J. The Secret History of Gender: Women, Men, and Power in Late Colonial Mexico. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 1995.

- Thompson, Lanny. “La fotografía como documento histórico: la familia proletaria y la vida domestica en la ciudad de México, 1900-1950.” Historias 29 (October 1992-March 1993).

- Towner, Margaret. "Monopoly Capitalism and Women's Work during the Porfiriato" Latin American Perspectives 2 (1979)

- Tuñon Pablos, Esperanza. "Women's Status and Occupation, 1910-96," in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 2 pp. 1626-1629. Chicago: Fitzroy and Dearborn 1997.

- Tuñon Pablos, Julia. Women in Mexico: A Past Unveiled. Trans. Alan Hynd. Austin: University of Texas Press 1999.

- Vaughan, Mary Kay. Cultural Politics in Revolution: Teachers, Peasants, and Schools in Mexico, 1930-1940. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1997.

- Villaba. Angela. Mexican Calendar Girls: Golden Age of Calendar Art, 1930-1960. San Francisco: Chronicle Books 2006.

- Walker, Louise. Waking from the Dream: Mexico's Middle Class after 1968. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2013.

- Wood, Andrew Grant. "Introducing La Reina de Carnaval: Public Celebration and Postrevolutionary Discourse in Veracruz". The Americas. 60 (1): 87–107. doi:10.1353/tam.2003.0090. S2CID 144272877.

- Zavala, Adriana. Becoming Modern, Becoming Tradition: Women, Gender and Representation in Mexican Art. State College: Penn State University Press 2010.

External links

- An Introduction to Mexico & the Role of Women (INTRODUCCIÓN DE MEXICO Y EL PAPEL DE LA MUJER) by Celina Melgoza Marquez, West Virginia University

.jpg.webp)