| Millennium |

|---|

| 2nd millennium |

| Centuries |

| Decades |

| Years |

| Categories |

|

The 1820s (pronounced "eighteen-twenties") was a decade of the Gregorian calendar that began on January 1, 1820, and ended on December 31, 1829.

It saw the rise of the First Industrial Revolution. Photography, rail transport, and the textile industry were among those that largely developed and grew prominent over the decade, as technology advanced significantly. European colonialism began gaining ground in Africa and Asia, and trade with the Qing Dynasty began to open up more towards foreign traders, particularly those from Europe. As European imperialism gained momentum, opposition from affected/exploited societies resulted, with wars such as the Java War and the Greek War of Independence. Resistance in the form of separatism and nationalism (particularly in the Spanish American wars of independence) led to the independence of many countries around the world, such as Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia.

Politics and wars

The Greek War of Independence and the Russo-Turkish War were two of the decade's more important conflicts. Meanwhile, colonialism in Africa had just begun to accelerate, and global trade between Asian powers (e.g. the Qing Dynasty) with European powers (mainly the British and French empires) increased substantially. In South America, states such as Bolivia, Peru, and Brazil gained independence from the Spanish Empire and Portuguese Empire.

Global

- 1820: Anchor coinage is issued for use in some British colonies.

East Asia

Indonesia

- 1824 – The Dutch sign the Masang Agreement, temporarily ending hostilities in the Padri War in West Sumatra.

Java War

The Java War (also known as the "Diponegoro War") was fought in Java between 1825 and 1830. It started as a rebellion led by Prince Diponegoro after the Dutch decided to build a road across a piece of his property that contained his parents' tomb.

The troops of Prince Diponegoro were very successful in the beginning, controlling the middle of Java and besieging Yogyakarta. Furthermore, the Javanese population was supportive of Prince Diponegoro's cause, whereas the Dutch colonial authorities were initially very indecisive. As the Java war prolonged, Prince Diponegoro had difficulties in maintaining the numbers of his troops. Prince Diponegoro started a fierce guerrilla war and it was not until 1827 that the Dutch army gained the upper hand. The Dutch colonial army was able to fill its ranks with troops from Sulawesi, and later on from the Netherlands.

The rebellion finally ended in 1830, after Prince Diponegoro was tricked into entering Dutch custody near Magelang, believing he was there for negotiations for a possible cease-fire. It is estimated that 200,000[1] died over the course of the conflict, 8,000 being Dutch.[1]

Malaysia

- November 1821 - Siamese invasion of Kedah – The Siamese forces of King Rama II achieved a rapid victory against those of Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin Halim Shah II of Kedah, in what is now northern Malaysia. The campaign initiated a period of two decades in which Kedah resisted Siamese control. The Sultan took refuge on Penang Island, then under British control.[2] By 1822 there was a rise in the population of the British territories caused by an influx of Malays displaced by the invasion.[3]

- 1826 – The Burney Treaty allowed the Siamese view of their rights to prevail in Kelah.[4]

- 1826 – The British crown colony of the Straits Settlements is established in what is now Malaysia and Singapore.

Vietnam

- February 14, 1820 – Minh Mang starts to rule in Vietnam.

- 1825 – Minh Mang outlaws the teaching of Christianity in Vietnam.

Laos

- 1827: King Anouvong of Vientiane declares war on Siam and successfully attacks Nakhon Ratchasima.

- 1828 Siamese-Lao War: The Siamese invade and sack the city of Vientiane.

- November 12, 1828: Anouvong is deposed and his kingdom is annexed by Siam. Large forced population transfers are made from Laos to the more securely held area of Isan, and the Lao mueang is divided into smaller units to prevent another uprising.

Burma

- 1824–1826: The First Anglo-Burmese War ended in a British victory, and by the Treaty of Yandabo, Burma lost territory previously conquered in Assam, Manipur, and Arakan.[5] The British also took possession of Tenasserim with the intention to use it as a bargaining chip in future negotiations with either Burma or Siam.[6]

Siam (Thailand)

- 1824–1826 - Rattanakosin Kingdom (Siam): Rama II died in 1824 and was peacefully succeeded by his son Jessadabodindra (Rama III). In 1825 the British sent another mission to Bangkok led by East India Company emissary Henry Burney. They had by now annexed southern Burma and were thus Siam's neighbours to the west, and they were also extending their control over Malaya. The King was reluctant to give in to British demands, but his advisors warned him that Siam would meet the same fate as Burma unless the British were accommodated. In 1826, therefore, Siam concluded its first commercial treaty with a western power, the Burney Treaty. Under the treaty, Siam agreed to establish a uniform taxation system, to reduce taxes on foreign trade and to abolish some of the royal monopolies. As a result, Siam's trade increased rapidly, many more foreigners settled in Bangkok, and western cultural influences began to spread. The kingdom became wealthier and its army better armed.

Australia

- 1824 – The name Australia, recommended by Matthew Flinders in 1804, is finally adopted as the official name of the country once known as New Holland.

- September 13, 1824 – With his crew and 29 convicts aboard the Amity, John Oxley arrives at and founds the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement at what is now Redcliffe in Queensland, Australia, after leaving Sydney.

- December 25, 1826 – Major Edmund Lockyer arrives at King George Sound to take possession of the western part of Australia, establishing a settlement near Albany.

- June 3, 1829 – The Swan River Colony (later to become the cities of Perth and Fremantle) is founded in Western Australia. This secures the western 'third' of the Australian landmass for the British.

- August 12, 1829 – Mrs. Helen Dance, wife of the captain of the ship Sulphur, cuts down a tree to mark the day of the founding of the town of Perth, Western Australia.

Central Asia

- Caucasian War (1817–1864)

- 1826 – Britain annexes Assam.

South Asia

- Siege of Bharatpur – India (9 December 1825 – 18 January 1826) ended in British victory.

- December 4, 1829 – India: In the face of fierce opposition, British Lord William Bentinck carries a regulation declaring that all who abet suttee in India are guilty of culpable homicide.

Western Asia

- October 1, 1827 – Russo-Persian War, 1826–1828: The Russians under Ivan Paskevich storm Yerevan, ending a millennium of Muslim domination in Eastern Armenia.

- February 22, 1828 –Treaty of Turkmenchay: Russian-Persian peace treaty: Russia captures Eastern Armenia from Persia.

Europe

Eastern Europe

- April 6 1821 – The Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire is proclaimed officially in South Greece.

- June 19, 1821 – The Philikí Etaireía are decisively defeated by the Ottomans at Drăgăşani (in Wallachia).

- December 1825 – The Decembrist Revolt breaks out in Russia, but is thoroughly suppressed.

- December 1, 1825 – Nicholas I of Russia succeeds his older brother Alexander I.

- June 14–June 15, 1826 – The Auspicious Incident: Mahmud II, sultan of Ottoman Empire, crushes the last mutiny of janissaries in Istanbul.

- September 29, 1828 – Russo-Turkish War, 1828–1829: Varna is taken by the Russian army.

- July 2, 1829 – Russo-Turkish War, 1828–1829: Russian Field-Marshal Hans Karl von Diebitsch launches the Transbalkan offensive, which brings the Russian army within 68 km of Istanbul.

- September 16, 1829 – Russo-Turkish War, 1828–1829: The Treaty of Adrianople gains for Russia some territory at the mouth of the Danube and along the eastern coast of the Black Sea.

Northern Europe

- February 3, 1825 – Vendsyssel-Thy, once part of the Jutland peninsula that formed westernmost Denmark, becomes an island after a flood drowns its 1 km wide isthmus.

- September 27, 1825 - The world's first modern railway, the Stockton and Darlington Railway, opens with engineer George Stephenson driving the first public train pulled by the steam engine Locomotion No 1.[7]

- September 4, 1827 – Finland: The Great Fire of Turku destroys 3/4 of the city, with many human casualties.

Central Europe

- October 25, 1820 –November 20 – The Congress of Troppau (Opava) is convened between the rulers of Russia, Austria and Prussia.

- October–December, 1822 – Congress of Verona: Russia, Austria and Prussia approve French intervention in Spain.

- July 6, 1825 – The Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Beck gains possession of Glücksburg and changes his title to Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg. The line of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg later becomes the royal house of Greece, Denmark and Norway.

Southern Europe

- January 1, 1820 – A constitutionalist military insurrection at Cádiz leads to the summoning of the Spanish Parliament (March 7) (see Mid-nineteenth century Spain).

- March 9, 1820 – King Ferdinand VII of Spain accepts the new constitution, beginning the Liberal Triennium ("Trienio Liberal").

- July 1820 – A Constitutionalist revolution occurs in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

- August 24, 1820 – A Constitutionalist insurrection breaks out at Oporto, Portugal.

- September 15, 1820 – A revolution breaks out in Lisbon (see Portugal's crises of the Nineteenth Century).

- September 22, 1822 – Portugal approves its first Constitution.[8]

- January 4, 1825 – King Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies is succeeded by his son Francis I of the Two Sicilies.

- May 28, 1826 – Pedro I of Brazil abdicates as King of Portugal.

- June 23, 1828 – Portugal: King Miguel I overthrows his niece Queen Maria II, beginning the Liberal Wars.

Greek War of Independence

At the start of the decade, most of Greece was under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, as it had been since 1453, despite frequent revolts.[9] In early 1821, a secret organization called the Filiki Eteria instigated several battles that, together with the blessing of a Greek flag and proclamation of uprising by Bishop Germanos of Patras on March 25, marked the beginning of the revolution.[10][11][12] The uprising successfully established a foothold in the Peloponnese, seizing Tripolitsa in September 1821, and had some success in Crete, Macedonia and Central Greece.

Between 1821 and 1824, first and second national assemblies were held, and the constitutions of 1822 and of 1823 were established. However, revolutionary activity was fragmented, resulting in the civil wars of 1824–1825. The Greek side withstood the Turkish attacks because, during this period, the Ottoman military campaigns were periodic and uncoordinated.

That changed when the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II negotiated with Mehmet Ali of Egypt, who agreed to send his son Ibrahim Pasha to Greece with an army to suppress the revolt in return for territorial gain. Ibrahim landed in the Peloponnese in February 1825 and secured most of the peninsula by the end of 1825. He then helped break the siege of Missolonghi. Although Ibrahim was defeated in Mani, he had succeeded in suppressing most of the revolt in the Peloponnese and Athens had been retaken.

Following years of negotiation, three Great Powers, Russia, the United Kingdom and France had come to agree to the formation of an autonomous Greek state under Ottoman suzerainty, as stipulated in the Treaty of London. Ottoman refusal to accept these terms led to the Battle of Navarino, which effectively secured complete Greek independence. That year, the Third National Assembly at Troezen established the First Hellenic Republic. With the help of a French expeditionary force, the Greeks drove the Turks out of the Peloponnese and proceeded to the captured part of Central Greece by 1828. As a result of years of negotiation, Greece was finally recognized as an independent nation in May 1832.

Western Europe

United Kingdom

In the 1820s, the British government was formally headed by King George IV, but in practice, was led by his prime ministers Lord Liverpool (1812–1827), George Canning (1827), Lord Goderich (1827–1828), and Duke of Wellington (1828–1830). This decade was largely peaceful for Britain, with some foreign intervention. The British supported the Portuguese liberals in the Liberal Wars, and supported Greek rebels in the war for independence. During this time, London became the largest city of the world, taking the lead from Beijing.[13]

Domestic tensions ran high at the start of the decade, with the Peterloo Massacre (1819), the Cato Street Conspiracy (1820), and the Radical War (1820) in Scotland. However, by the end of the 1820s, many repressive laws were repealed. In 1822, Britain repealed the death penalty for over 100 crimes, and punishments such as drawing and quartering and flagellation fell out of use. Seditious Meetings prevention Act (barring large assemblies) and the Combination Act (banning trade unions) were repealed in 1824. The Roman Catholic Relief Act by Parliament of the United Kingdom granted a substantial measure of Catholic Emancipation in Britain and Ireland.[7]

France

- May 5, 1821 – Emperor Napoléon I dies in exile on Saint Helena of stomach cancer.

- September 16, 1824 – Charles X succeeds his brother Louis XVIII as King of France.

- January 4, 1828 – France: The Vicomte de Martignac succeeds the Comte de Villèle as Prime Minister of France.

- August 8, 1829 – France: The Prince de Polignac succeeds the Vicomte de Martignac as Prime Minister of France.

Africa

- February 6, 1820: 86 free African American colonists sail from New York City to Freetown, Sierra Leone.

- Americo-Liberians begin to settle in the Colony of Liberia with the support of the American Colonization Society

- June 14, 1821 – King Badi VII of Sennar surrenders his throne and realm to Ismail Pasha, general of the Ottoman Empire, ending the existence of that Sudanese kingdom.

- 1822 – The first group of freed slaves from the United States arrive in modern-day Liberia and found Monrovia (see History of Liberia).

- January 22, 1824 – The Ashanti crush British forces in the Gold Coast, killing the British governor Sir Charles MacCarthy (see also Wars between Britain and Ashanti in Ghana and Ashanti Confederacy).

- August 18, 1826 – Explorer Alexander Gordon Laing becomes the first European to reach Timbuktu.[7]

- April 1827 – Ottoman Algeria: Husain Dei slaps the French consul Decalina on the face, eventually leading to war and French rule in Algeria.

North America

Canada

- July 8, 1822 – The Chippewas turn over huge tract of land in Ontario to the United Kingdom.

- November 30, 1824 – The first sod is turned in Ontario, for the first of four Welland Canals (the canal opens for a trial run exactly 5 years later to the day).

United States

At the beginning of the 1820s, the United States stretched from the Atlantic Ocean through to (roughly) the western edge of the Mississippi basin, though Florida, Michigan, Wisconsin and all present-day states fully west of the Mississippi had yet to be granted statehood. Two states were admitted to the union during this decade: Maine in 1820 and Missouri in 1821. The Adams–Onís Treaty, signed in 1819 and ratified by Spain in 1821, ceded Florida to the United States, and established a boundary between New Spain and the United States.

Slavery was widespread throughout the southern United States. According to the 1820 U.S. Census, the slave population at that time was 1,538,000.[14] The Missouri Compromise of 1820 prohibited slavery in the former Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30′ north except within the boundaries of the proposed state of Missouri. By the 1830 U.S. Census, the slave population had risen to 2,009,043.[14] With the coordination of the American Colonization Society, many freed African-Americans repatriated to Africa during this decade to the newly formed colony of Liberia.

The political mood at the start of the 1820s was referred to as the Era of Good Feelings, following the collapse of the Federalist party. James Monroe, the sitting U.S. president since 1817, was re-elected in 1820, virtually unopposed. In 1823, Monroe introduced the Monroe Doctrine in the State of the Union Address, declaring that any European attempts to recolonize the Americas would be considered a hostile act towards the United States.

The feeling of unity during the Monroe administration was dispelled in the presidential election of 1824, which due to an Electoral College stalemate, was decided in the United States House of Representatives. John Quincy Adams was chosen as the sixth U.S. president, despite receiving only 30.9% of the popular vote to Andrew Jackson's 41.3%. This gave rise to Jacksonian Nationalism and the rise of the modern Democratic Party,[15] with Andrew Jackson elected in the 1828 election.

Mexico

After ten years of civil war in Mexico (then called the "Viceroyalty of New Spain") and the death of two of its founders, by early 1820 the Mexican independence movement was stalemated and close to collapse. However, the Army of the Three Guarantees was formed under the command of Colonel Agustín de Iturbide with the support of patriots and loyalists to secure independence for Mexico and the protection of Roman Catholicism. Iturbide's army was joined by rebel forces from all over Mexico, and quickly gained control of Mexico. On August 24, 1821, representatives of the Spanish crown and Iturbide signed the Treaty of Córdoba, which recognized the Mexican Empire under the terms of the Plan of Iguala.

On September 27 the Army of the Three Guarantees entered Mexico City, and the following day Iturbide proclaimed the independence of the Mexican Empire. The newly formed Mexican congress eventually declared Iturbide emperor of Mexico on May 19, 1822. Later that year, Iturbide dissolved Congress and replaced it with a sympathetic junta. However, on March 19, 1823 Iturbide abdicated.

The First Federal Republic was established on October 4, 1824. In the new constitution, the republic took the name of United Mexican States, and was defined as a representative federal republic, with Catholicism as the official and unique religion.[16] Guadalupe Victoria was the first President of Mexico from 1824 until 1829.

After Manuel Gómez Pedraza won the election to succeed Victoria, Vicente Guerrero staged a coup d'état and took the presidency on April 1, 1829.[17] Guerrero was deposed in a rebellion under Vice-president Anastasio Bustamante in December 1829.

Caribbean

- December 1, 1821 – The Dominican Republic declares independence from Spain only to be invaded by Haiti in 1822 (see History of the Dominican Republic).

- February 9, 1822 – The invading Haitian forces led by Jean-Pierre Boyer arrive in Santo Domingo, to overthrow the newly founded Republic.

- April 17, 1825 – Charles X of France recognizes Haiti, 21 years after it expelled the French following the successful Haitian Revolution, and demands the payment of 150 million gold francs, 30 million of which Haiti must finance through France itself, as down payment.

Central America

- February 20, 1820 – A revolt begins in Santa María Chiquimula, Totonicapán department of Guatemala.

- The United Provinces of Central America were formed in 1823.

- September 15, 1821 – Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica gain independence from Spain (see History of Central America).

- November 28, 1821 – Panama declares independence from Spain (see History of Panama).

- July 1– The congress of Central America declares absolute independence from Spain, Mexico, and any other foreign nation, including North America and a Republican system of government is established.

- June 22, 1826 – The Pan-American Congress of Panama tries (unsuccessfully) to unify the American republics.

South America

Gran Colombia

- October 9, 1820 – Guayaquil declares independence from Spain (see also History of Ecuador).

- June 24, 1821 – Battle of Carabobo: Simón Bolívar wins Venezuela's independence from Spain (see Venezuela's independence).

- September 7, 1821 – The Republic of Gran Colombia (a federation covering much of present-day Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, and Ecuador) is established, with Simón Bolívar as the founding President and Francisco de Paula Santander as vice president.

- May 24, 1822 – Battle of Pichincha: Simón Bolívar secures the independence of Quito.

- July 26, 1822 – José de San Martín arrives in Guayaquil, Ecuador, to meet with Simón Bolívar.

- July 27, 1822 – Simón Bolívar and General José de San Martín meet in Guayaquil. Bolívar later annexes Guayaquil (See Guayaquil Conference).

- June 3, 1828 – Gran Colombia – Peru War: President Simón Bolívar declares war on Peru.

- August 27, 1828 – Simón Bolívar declares himself dictator of Gran Colombia.

Bolivia

- August 6, 1825 – Bolivia gains its independence from Spain as a republic with the instigation of Simón Bolívar.

Peru

- July 28, 1821 – Peru declares independence from Spain (see Peru's Independence from Spain).

- September 10, 1823 – Simón Bolívar is named President of Peru.

- February 10, 1824 – Simón Bolívar is proclaimed dictator of Peru.

- December 9, 1824 – Battle of Ayacucho: Peruvian forces defeat the Spanish.

- February 10, 1825 – Simón Bolívar gives up his title of dictator of Peru and takes the alternative title of Liberator.

Brazil

- 1822: Brazil gains independence

- September 7, 1822 – Brazil declares its independence from Portugal (see Brazilian independence).

- October 12, 1822 – Peter I of Brazil is declared the constitutional emperor of the Brazilian Empire.

- December 1, 1822 – Peter I is crowned as Emperor of Brazil (see The reign of Pedro I, 1822–31).

- April 26, 1828 – Treaty of Commerce and Navigation signed between Brazil and Denmark, establishing diplomatic relations between the two countries.[18]

Argentina–Brazil War

- March 7, 1827 – Brazilian marines sail up the Rio Negro and attack the temporary naval base of Carmen de Patagones, Argentina; they are defeated by the local citizens.

- April 7–April 8, 1827 – Battle of Monte Santiago: A squadron of the Brazilian Imperial Navy defeats Argentine vessels in a major naval engagement.

- February 20, 1827 – Battle of Ituzaingo (Passo do Rosário): A force of the Brazilian Imperial Army meets Argentine–Uruguayan troops in combat.

- August 27, 1828 – South America: Brazil and Argentina recognize the independence of Uruguay.

Uruguay

- July 18, 1825 – Uruguay declares independence from Brazil (see Uruguay's independence).

- August 27, 1828 – South America: Brazil and Argentina recognize the independence of Uruguay.

Argentina

- 1820: The Argentine Confederation (Argentina) establishes a penal colony in the Malvinas.

- February 8, 1826 – Unitarian Bernardino Rivadavia becomes the first President of Argentina.

Chile

- February 6, 1820 – Lord Cochrane occupies Valdivia in the name of the Republic of Chile.

- September 4, 1821 – Chilean general José Miguel Carrera is executed by an Argentinian military tribunal in the city of Mendoza.

Pacific Islands

- August 21, 1821 – Jarvis Island is discovered by the crew of the Eliza Frances.

- July 14, 1827 – Kingdom of Hawaii: The Diocese of Honolulu is founded.

Economics and commerce

- 1821: High-quality cotton is introduced in Egypt.

- 1822 – Ashley's Hundred leave from St. Louis, setting off a major increase in fur trade.

- 1822 – Coffee is no longer banned in Sweden.

- 1824 – The construction of Fort Vancouver trading post started on the North shore of the lower Columbia River by the Hudson's Bay Company. Inauguration occurred the following year when Fort George was closed.

- August 18, 1825 – Gregor MacGregor issues a £300,000 loan with 2.5% interest through the London bank of Thomas Jenkins & Company. His actions lead to the Panic of 1825, the first modern stock market crash in London.

Slavery, serfdom and labor

- March 3, 1820 and March 6, 1820 – Slavery in the United States: The Missouri Compromise becomes law.

- 1820: Robert Owen devises the labour voucher.

- 1820: 18,957 black slaves leave Luanda, Angola.

- 1828 – 32,000 Angolans are sold in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- June 5, 1829 – Slave trade: HMS Pickle captures the armed slave ship Voladora off the coast of Cuba.

Science and technology

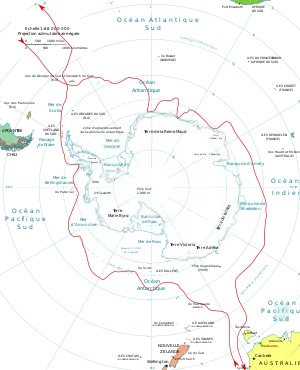

- January 28, 1820 – A Russian expedition led by Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Petrovich Lazarev approaches the Antarctic coast (see History of Antarctica).

- January 30, 1820 – Edward Bransfield lands on the Antarctic mainland (see History of Antarctica).

- April 1820 – Hans Christian Ørsted discovers the relationship between electricity and magnetism.

- May 11, 1820 – HMS Beagle (the ship that later takes young Charles Darwin on his scientific voyage) is launched.

- 1820: The 6th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica appears.

- June 14, 1822 – Charles Babbage proposes a Difference engine.

- 1822 – Hieroglyphs are deciphered by Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion, using the Rosetta Stone.

- 1822 – Galileo Galilei's Dialogue is taken off the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the Roman Catholic Church's list of banned books.

- 1822 – The Graham Cracker is developed in Bound Brook, New Jersey by the Presbyterian minister Sylvester Graham.

- 1823 – Olbers' paradox is described by the German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers.

- January 8, 1824 – After much controversy, Michael Faraday is finally elected as a member of the Royal Society with only one vote against him.

- October 21, 1824 – Joseph Aspdin patents Portland Cement.

- 1824 – The Panoramagram is developed, creating the first volumetric display.

- 1824- Gideon Mantell and Mary Anning discover an Iguanodon tooth and Megalosaurus skeletons not far from their home in England giving birth to Paleontology.

- 1825 – Hans Christian Ørsted reduces aluminium chloride to make aluminium.

- June 1826 – Photography: Nicéphore Niépce makes a true photograph.

- 1826 – Aniline is first isolated from the destructive distillation of indigo by Otto Unverdorben.

- May 25, 1827 – Romanian inventor Petrache Poenaru receives a French patent for the invention of the first fountain pen with a replaceable ink cartridge.

- 1827 – Englishman John Walker invents the first friction match which he names Lucifer.

- 1828 – Friedrich Wöhler synthesizes urea, implicitly discrediting a cornerstone of vitalism.

- 1828 – Ányos Jedlik creates the world's first electric motor.

- 1828 – Casparus van Houten Sr. (father of Coenraad Johannes van Houten) patents an inexpensive method for pressing cocoa butter from roasted cocoa beans,[19] leaving cocoa solids. This is an important step in modern solid chocolate production.

- May 6, 1829 – The patent for an instrument called the accordion is applied for by Cyrill Demian (Officially approved on May 23.)

- July 23, 1829 – In the United States, William Burt obtains the first patent for a form of typewriter.

Transportation

- 1825 – The first horse-drawn omnibuses established in London.

- September 27, 1825 – The world's first modern railway, the Stockton and Darlington Railway, opens in England.

- October 26, 1825 – The Erie Canal opens, providing passage from Albany, New York to Buffalo and Lake Erie.

- 1825: The Ohio and Erie Canal is dug to extend settlement access and commercial traffic to the Ohio River.

- January 30, 1826 – The Menai Suspension Bridge, built by engineer Thomas Telford, is opened between the island of Anglesey and the mainland of Wales.

- April 1, 1826 – Samuel Morey patents the internal combustion engine.

- October 1, 1826 – Opening of the Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway in Scotland.[20]

- September 21, 1826 – Construction of the Rideau Canal begins in Canada.

- October 7, 1826 – The first train operates over the Granite Railway in Massachusetts.[21][22]

- 1826 – The first railway tunnel is built en route between Liverpool and Manchester in England.

- February 28, 1827 – The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad is incorporated, becoming the first railroad in United States offering commercial transportation of both people and freight.

- April 26–May 24, 1827 - The Royal Netherlands Navy's British-built paddle steamer Curaçao makes the first Transatlantic Crossing by steam, from Hellevoetsluis to Paramaribo.[23]

- July 4, 1829 – George Shillibeer begins operating the first bus service in London.[24]

- October 8, 1829 – Rail transport: Stephenson's Rocket wins the Rainhill Trials.

- November 30, 1829 – The original Welland Canal opens for a trial run with a ceremony at Port Dalhousie.

Culture

Literature

- 1824–1825: The earliest history of American literature by John Neal is published in Blackwood's Magazine[25]

Music

- February 3, 1823 – Gioachino Rossini's Semiramide is first performed.

- April 13, 1823 – Eleven-year-old Franz Liszt gives a concert after which he is personally congratulated by Ludwig van Beethoven.

- May 7, 1824 – One of Beethoven's most notable pieces, his Symphony No. 9, premieres in Vienna.

- Early July, 1826 – Ludwig van Beethoven puts the finishing touches on the String Quartet in C sharp Minor, Opus 131.

- 1826 – Ludwig van Beethoven composes the Große Fuge.

- March 11, 1829 – Felix Mendelssohn performs Bach's St Matthew Passion.

- April–September – Felix Mendelssohn pays his first visit to Britain. This includes the first London performance of his concert overture to A Midsummer Night's Dream and his trip to Fingal's Cave.[26]

Art

- 1820: Venus de Milo is found on the island of Melos (Milos).

Poetry

- 1820: John Keats completes Ode on Melancholy, one in a series of his famous Odes.

- 1820: John Clare 13 July 1793 - 20 May 1864 publishes Poems Descriptive of Rural life 1820

- 1826: Felicia Hemans publishes Casabianca, a poem commemorating the sinking of a French ship called the Orient during The Battle of the Nile in 1798.

Sports

- 1823 – William Webb Ellis "invents" Rugby football.

- August 10, 1826 – The first Cowes Regatta is held on the Isle of Wight in the UK.[24]

- June 10, 1829 – The Oxford University Boat Club wins the very first boat race.[7][27]

- August 10, 1829 – First ascent of Finsteraarhorn, the highest summit of the Bernese Alps.

Theatre

- January 19, 1829 – August Klingemann's adaptation of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Faust premieres in Braunschweig.[28]

Fashion

During the 1820s in European and European-influenced countries, fashionable women's clothing styles transitioned away from the classically influenced "Empire"/"Regency" styles of ca. 1795–1820 (with their relatively unconfining empire silhouette) and re-adopted elements that had been characteristic of most of the 18th century (and were to be characteristic of the remainder of the 19th century), such as full skirts and clearly visible corseting of the natural waist.

The silhouette of men's fashion changed in similar ways: by the mid-1820s coats featured broad shoulders with puffed sleeves, a narrow waist, and full skirts. Trousers were worn for smart day wear, while breeches continued in use at court and in the country.

Miscellaneous

- May 26, 1828 – Feral child: Kaspar Hauser is discovered in Nuremberg, Germany.

- 1822 Jean-François Champollion cracks the hieroglyphic code by using the Rosetta Stone.

Establishments

- July 20, 1820 – Saint Cronan's Boys National School opens in Bray, County Wicklow, Ireland under the title Bray Male School. It is the oldest school in Bray and its notable past pupils include the former president of Ireland, Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh.

- 1820: Indiana University is founded as the Indiana State Seminary and renamed the Indiana College in 1846, to later be renamed Indiana University.

- February 9, 1821 – The George Washington University is chartered as The Columbian College of the District of Columbia by President Monroe.

- June 27, 1821 – The New Hampton School is founded in the United States state of New Hampshire.

- September 18, 1821 – Amherst College is founded in Massachusetts.

- 1822 – Aban Palace is completed.

- August 12, 1822 – St David's College (now the University of Wales, Lampeter) is founded by Bishop Thomas Burgess.

- November 13, 1822 – founding of the Congregation of St. Basil

- June 5, 1823 – Raffles Institution, then the Singapore Institution, was founded by the founder of Singapore, Sir Stamford Raffles.

- 1823 – Jackson Male Academy, precursor of Union University, is founded in Tennessee.

- 1823 – The Oxford Union is founded.

- January 24, 1824 – The Westminster Review, No1. is published.

- June 16, 1824 – Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals is established in Great Britain.

- October 10, 1824 – The Edinburgh Town Council makes a decision to found the Edinburgh Municipal Fire Brigade, the first fire brigade in Britain.

- November 5, 1824 – Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (the first technological university in the English-speaking world) is founded in Troy, New York.

- December 24, 1824 – The First American Fraternity, Chi Phi (ΧΦ), is founded at Princeton University.

- 1824 – The Cimetière du Montparnasse is established in Paris, France.

- September 1825 – The Lady Margaret Boat Club is founded by 12 members of St John's College, Cambridge.

- 1825 – The City of Brisbane is founded (see History of Brisbane).

- 1825 – The United States Postal Service started a dead letter office.

- February 11, 1826 – University College London is founded, under the name University of London.

- February 13, 1826 – The American Temperance Society is founded.

- March 16, 1827 – Freedom's Journal, the first African-American owned and published newspaper in the United States, is founded in New York City by John Russwurm.

- 1827 – Egypt: Cairo University School of Medicine is established as the first African medical school in the Middle East.

- 1827 – J. J. Audubon begins publishing Birds of America.

- April 11, 1828 – Bahía Blanca is founded.

- June 1, 1829 – The Philadelphia Inquirer is founded as The Pennsylvania Inquirer.

- October 1, 1829 – South African College inaugurated in Cape Town.

- 1829 – King's College London is founded under the patronage of King George IV and the prime minister The Duke of Wellington. It will become the third official university in England.

- 1829 – The Chalmers University of Technology is founded in Gothenburg.

Disasters, natural events, and notable mishaps

- November 20, 1820 After the sinking of the Essex (1799 whaleship) of Nantucket by a whale the survivors were left floating in three small whaleboats. They eventually resorted, by common consent, to cannibalism to allow some to survive.

- 1820: Mount Rainier erupts over what is today Seattle.

- February 6, 1822 – Chinese junk Tek Sing sinks in the South China Sea with the loss of around 1600 people on board.

- May 26, 1822 – 116 people die in the Grue Church fire, the biggest fire disaster in Norway's history.

- 1822 – An earthquake in Chile raises the coastal area.

- July 15, 1823 – The Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome is almost completely destroyed by fire.

- November 7, 1824 – In the worst flood to date in Saint Petersburg, water rises 421 cm above normal and 200 lose their lives.

- October 7, 1825 – The Miramichi Fire breaks out in New Brunswick.

- August, 1826 – The town of Crawford Notch suffers a landslide, killing nine people. Those killed include seven members of the Willey family, after whom Mount Willey is named.

- 1828 – A typhoon kills approximately 10,000 people in Kyūshū, Japan.

Religion

- 1820: Joseph Smith receives his First Vision in the spring in Palmyra, New York.

- September 22, 1823 – Joseph Smith says that he was directed by God through the angel Moroni to the place where the Golden plates are stored.

- February 11, 1826 – Swaminarayan writes the Shikshapatri, an important text within the Swaminarayan faith.

- July 26, 1826 – The last auto-da-fé is held in Valencia, Spain.

- March 31, 1829 – Pope Pius VIII succeeds Pope Leo XII as the 253rd pope.

- June 19, 1829 – Robert Peel's Metropolitan Police Act establishes the Metropolitan Police Service in London, the first modern police force. The first officers, known by the nicknames "bobbies" or "peelers", go on patrol on September 29.[7]

People

Authors

References

- 1 2 M. C. RicKlefs: A History of modern Indonesia since 1300, p. 117.

- ↑ "Siam, Cambodia, and Laos 1800-1950 by Sanderson Beck". www.san.beck.org.

- ↑ Nordin Hussin (2007). Trade and Society in the Straits of Melaka: Dutch Melaka And English Penang, 1780–1830. NIAS Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-87-91114-88-5. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ Frank Athelstane Swettenham, Map to Illustrate the Siamese Question (1893) p. 62; archive.org.

- ↑ Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur P. Phayre (1967). History of Burma (Second ed.). London: Susil Gupta. pp. 236–247.

- ↑ D. G. E. Hall (1960). Burma (PDF). Hutchinson University Library. pp. 109–113. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-05-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Penguin Pocket On This Day. Penguin Reference Library. 2006. ISBN 0-14-102715-0.

- ↑ "The Constitutional Monarchy". Assembly of the Republic of Portugal. 2013-10-22. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ↑ Woodhouse, A Story of Modern Greece, 'The Dark Age of Greece (1453–1800)', p. 113, Faber and Faber (1968)

- ↑ "Greek Independence Day". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

The Greek revolt was precipitated on March 25 (April 6 in Gregorian Calendar), 1821, when Bishop Germanos of Patras raised the flag of revolution over the Monastery of Agia Lavra in the Peloponnese. The cry "Freedom or Death" became the motto of the revolution. The Greeks experienced early successes on the battlefield, including the capture of Athens in June 1822, but infighting ensued.

- ↑ Frazee, Charles A. (1969). The Orthodox Church and independent Greece, 1821–1852. CUP Archive. pp. 18–20. ISBN 0-521-07247-6.

On 25 March, Germanos gave the revolution its great symbol when he raised a banner with the cross on it at the monastery of Ayia Lavra.

- ↑ McManners, John (2001). The Oxford illustrated history of Christianity. Oxford University Press. pp. 521–524. ISBN 0-19-285439-9.

The Greek uprising and the church. Bishop Germanos of old Patras blesses the Greek banner at the outset of the national revolt against the Turks on 25 March 1821. The solemnity of the scene was enhanced two decades later in this painting by T. Vryzakis….The fact that one of the Greek bishops, Germanos of Old Patras, had enthusiastically blessed the Greek uprising at the onset (25 March 1821) and had thereby helped to unleash a holy war, was not to gain the church a satisfactory, let alone a dominant, role in the new order of things.

- ↑ "Largest Cities Through History". About.com Geography. Archived from the original on 2016-08-18. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- 1 2 Population Division. "Selected Historical Decennial Census Population and Housing Counts". US Census.

- ↑ Brown, 1966, p. 22

- ↑ "Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States (1824)". Archived from the original on March 18, 2012.

- ↑ Katz, William Loren. "The Majestic Life of President Vicente Ramon Guerrero". William Loren Katz. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ↑ British and Foreign State Papers. Great Britain. Foreign Office. 1829 – via Harvard University.

- ↑ "Onderzoekers in actie: Peter van Dam De geschiedenis van de firma Van Houten Cacao" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. Wellingborough: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 1-85260-049-7.

- ↑ "Granite Railway". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ "The First Railroad in America". Catskill Archive. Granite City B.P.O.E. - Quincy Lodge No. 943. 1924. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ "Steamship Curaçao". Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- 1 2 "Icons, a portrait of England 1820–1840". Archived from the original on 22 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-8057-7230-2.

- ↑ Grove, George (1 October 1904). "Mendelssohn's Scotch Symphony". The Musical Times. 45 (740): 644. doi:10.2307/904111. JSTOR 904111.

- ↑ "Origins Of The Boat Races". Archived from the original on November 27, 2011.

- ↑ Richard Acland Armstrong (1881). The Modern review. J. Clarke & Co. pp. 152–. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

.jpg.webp)