| Dongba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | Pictographic

|

Time period | At least 30 C.E. to the present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Naxi language |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Nkdb (085), Naxi Dongba (na²¹ɕi³³ to³³ba²¹, Nakhi Tomba) |

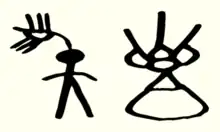

The Dongba, Tomba or Tompa or Mo-so symbols are a system of pictographic glyphs used by the ²dto¹mba (Bon priests) of the Naxi people in southern China. In the Naxi language it is called ²ss ³dgyu 'wood records' or ²lv ³dgyu 'stone records'.[1] The first artifacts with this script on them originate from approximately 30 AD.[2]

The glyphs may be used as rebuses for abstract words which do not have glyphs. Dongba is largely a mnemonic system, and cannot by itself represent the Naxi language; different authors may use the same glyphs with different meanings, and it may be supplemented with the geba syllabary for clarification.

Origin and development

_2087.jpg.webp) | _2088.jpg.webp) |

The Dongba script appears to be an independent ancient writing system, though presumably it was created in the environment of older scripts. According to Dongba religious fables, the Dongba script was created by the founder of the Bön religious tradition of Tibet, Tönpa Shenrab (Tibetan: ston pa gshen rab) or Shenrab Miwo (Tibetan: gshen rab mi bo),[3] while traditional Naxi genealogies attribute the script to a 13th-century king named Móubǎo Āzōng.[4] From Chinese historical documents, it is clear that dongba was used as early as the 7th century, during the early Tang dynasty. By the Song dynasty in the 10th century, dongba was widely used by the Naxi people.[3] It continues to be used in certain areas; thus, it is the only pictographic writing system in the world still actively maintained.

Chinese historical documents called Naxi 納西 as Mosuo or Moso or Mo-so (麽些 mósuò, "tiny little"), The Dongba script was called Les Mo-So: Ethnographie des Mo-so Écriture by Jacques Bacot on 1913. Dongba means Priest.

After the conclusion of the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949, the use of Dongba was discouraged.

In 1957, the Chinese government implemented a Latin-based phonographic writing system for Naxi.[5]

During the Cultural Revolution, thousands of manuscripts were destroyed. Paper and cloth writings were boiled into construction paste for building houses. About half of the dongba manuscripts that survive today had been taken from China to the United States, Germany and Spain.

Today Dongba is nearly extinct, and the Chinese government is trying to revive it in an attempt to preserve Naxi culture.[6]

Usage

The script was originally used as a prompt for the recitation of ritual texts.[7] For inventories, contracts, and letters, the geba script was used. Milnor concludes it is "unlikely that it [the Dongba script] would make the minor developmental leap to becoming a full-blown writing system. It arose a number of centuries ago to serve a particular ritual purpose. As its purpose need not expand to the realm of daily use among non-religious specialists—after all, literate Naxi today, as in the past, write in Chinese—at most it will presumably but continue to fulfill the needs of demon exorcism, amusing tourists and the like."[8]

Tourists to southern China are likely to encounter Dongba in the Ancient City of Lijiang where many businesses are adorned with signs in three languages: Dongba, Chinese, and English.

Structure and form

Dongba is both pictographic and ideographic.[9] There are about a thousand glyphs, but this number is fluid as new glyphs are coined. Priests drew detailed pictures to record information, and illustrations were simplified and conventionalized to represent not only material objects but also abstract ideas. Glyphs are often compounded to convey the idea of a particular word. Generally, as a mnemonic, only keywords are written; a single pictograph can be recited as different phrases or an entire sentence.

Examples of Dongba rebus include using a picture of two eyes (myə3) to represent fate (myə3), a rice bowl for both xa2 'food' and xa2 'sleep', and a picture of a goral (se3) stands in for an aspectual particle. It has two variants ma˧ lɯ˥ ma˧ sa˧ (玛里玛莎文) and ʐər˧ dy˨˩/ʐər˧ k’o˧ (阮坷文).[10]

|  |  |  |  |

Writing media and tools

The Naxi name of the script, 'wood and stone records', testifies that Dongba was once carved on stone and wood. Nowadays it is written on handmade paper, typically from the trees Daphne tangutica and D. retusa.[11] The sheets are typically 28 by 14 cm, and are sewn together at the left edge, forming a book. The pages are ruled into four horizontal lines.[12] Glyphs are written from left to right and top to bottom.[1] Vertical lines are used to section off elements of the text (see image above), equivalent to sentences or paragraphs. Writing utensils include bamboo pens and black ink made from ash.

See also

References

- 1 2 He, 292

- ↑ Memory of the World: The Treasures That Record our History from 1700 BC to the Present Day (1st ed.). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. 2012. p. 36. ISBN 978-92-3-104237-9.

- 1 2 He, 144

- ↑ Ramsey, 268

- ↑ He, 313

- ↑ "Rune revival". The Economist. Vol. 437, no. 9215. October 10, 2020. p. 28.

- ↑ Yang, 118; Ethnologue: "[Dongba is] not practical for everyday use, but is a system of prompt-illustrations for reciting classic texts."Naxi at the Ethnologue Archived 2007-03-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Seaver Johnson Milnor, A Comparison Between the Development of the Chinese Writing System and Dongba Pictographs Archived 2007-03-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ On the Twenty-Eight Lunar Mansions Systems in Dabaism and Dongbaism and on the analysis of the two writing systems according to an innovative interpretation, cf. XU Duoduo. (2015). A Comparison of the Twenty-Eight Lunar Mansions Between Dabaism and Dongbaism. «Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies», 3 (2015) 2: 61-81 (links: 1. academia.edu; 2. Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine)

- ↑ "四种东巴文的调查与研究" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-03-06. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

- ↑ Yang, p.138

- ↑ Yang, p.140

- XU Duoduo. (2015). A Comparison of the Twenty-Eight Lunar Mansions Between Dabaism and Dongbaism. «Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies», 3 (2015) 2: 61-81 (links: 1. academia.edu; 2. Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies);

- Yang, Zhengwen (2008). Zhengwen Naxi Study Collection. Beijing: Culture Publisher. ISBN 978-7-105-08499-9.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1989). The Languages of China. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691014685.

- Fang, Guoyu (2008). Guoyu Naxi Study Collection. Beijing: Culture Publisher. ISBN 978-7-105-08271-1.

- He, Zhiwu (2008). Zhiwu Naxi Study Collection. Beijing: Culture Publisher. ISBN 978-7-105-09099-0.

- Crampton, Thomas (February 12, 2001). "Hieroglyphic Script Fights for Life". International Herald Tribune.

External links

- Edongba Input Dongba hieroglyphs and Geba symbols.

- Dr. Richard S. Cook, Naxi Pictographic and Syllabographic Scripts: Research notes toward a Unicode encoding of Naxi Archived 2015-07-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Lawrence Lo, Ancient Scripts: Naxi

- Dominique Ryon (1993). Grammatologie et anthropologie: déchiffrement des écritures hiéroglyphiques et réinterprétation de la nature linguistique de l'écriture Dongba (Yunnan, Chine). Université de Montréal. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- "Annals of Creation / 創世經". World Digital Library. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- 建立东巴文象形字典语料库的构想

- 东巴文通行字典的疏失与理想字典的编纂构想

- 我们将会更加了解东巴文字

- 云南民族出版社