| Gupta script (Late Brahmi script) | |

|---|---|

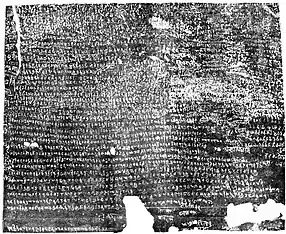

The Gopika Cave Inscription of Anantavarman, in the Sanskrit language and using the Gupta script. Barabar Caves in Jehanabad Bihar, 5th or 6th century CE. | |

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 4th–6th century CE[1] |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages | Sanskrit |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | |

Sister systems | Pallava script, Kadamba script, Sinhala, Tocharian |

The theorised Semitic origins of the Brahmi script are not universally agreed upon. | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

The Gupta script (sometimes referred to as Gupta Brahmi script or Late Brahmi script)[6] was used for writing Sanskrit and is associated with the Gupta Empire of the Indian subcontinent, which was a period of material prosperity and great religious and scientific developments. The Gupta script was descended from Brāhmī and gave rise to the Śāradā and Siddhaṃ scripts. These scripts in turn gave rise to many of the most important Indic scripts, including Devanāgarī (the most common script used for writing Sanskrit since the 19th century), the Gurmukhī script for Punjabi, the Bengali-Assamese script and the Tibetan script.

Origins and classification

The Gupta script was descended from the Ashokan Brāhmī script, and is a crucial link between Brahmi and most other Brahmic scripts, a family of alphasyllabaries or abugidas. This means that while only consonantal phonemes have distinct symbols, vowels are marked by diacritics, with /a/ being the implied pronunciation when the diacritic is not present. In fact, the Gupta script works in exactly the same manner as its predecessor and successors, and only the shapes and forms of the graphemes and diacritics are different.

Through the 4th century, letters began to take more cursive and symmetric forms, as a result of the desire to write more quickly and aesthetically. This also meant that the script became more differentiated throughout the Empire, with regional variations which have been broadly classified into three, four or five categories;[7][8] however, a definitive classification is lacking, because even in a single inscription, there may be variation in how a particular symbol is written. In this sense, the term Gupta script should be taken to mean any form of writing derived from the Gupta period, even though there may be a lack of uniformity in the scripts.

| k- | kh- | g- | gh- | ṅ- | c- | ch- | j- | jh- | ñ- | ṭ- | ṭh- | ḍ- | ḍh- | ṇ- | t- | th- | d- | dh- | n- | p- | ph- | b- | bh- | m- | y- | r- | l- | v- | ś- | ṣ- | s- | h- | |

| Brahmi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gupta | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Devanagari | क | ख | ग | घ | ङ | च | छ | ज | झ | ञ | ट | ठ | ड | ढ | ण | त | थ | द | ध | न | प | फ | ब | भ | म | य | र | ल | व | श | ष | स | ह |

Inscriptions

The surviving inscriptions of the Gupta script are mostly found on iron or stone pillars, and on gold coins from the Gupta Dynasty. One of the most important was the Prayagraj (Allahabad) Prasasti. Composed by Harishena, the court poet and minister of Samudragupta, it describes Samudragupta's reign, beginning from his accession to the throne as the second king of the Gupta Dynasty and including his conquest of other kings. It is inscribed on the Allahabad pillar of Ashoka.

Alphabet

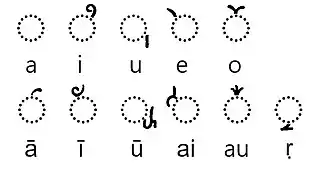

The Gupta alphabet is composed of 37 letters: 32 consonants with the inherent ending "a" and 5 independent vowels. In addition diacritics are attached to the consonants in order to change the sound of the final vowel (from the inherent "a" to other sounds such as i, u, e, o, au ...). Consonants can also be combined into compounds, also called conjunct consonants (for example sa+ya are combined vertically to give "sya").[10][11][12]

Independent vowels

| Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| a /ə/ | ā /aː/ | ||

| i /i/ | ī /iː/ | ||

| u /u/ | ū /uː/ | ||

| e /eː/ | o /oː/ | ||

| ai /əi/ | au /əu/ | ||

| 𑀋 | ṛ /r̩/ | 𑀌 | ṝ /r̩ː/ |

| 𑀍 | l̩ /l̩/ | 𑀎 | ḹ /l̩ː/ |

Consonants

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | ka /k/ | kha /kʰ/ | ga /g/ | gha /ɡʱ/ | ṅa /ŋ/ | ha /ɦ/ | ||||||||||

| Palatal | ca /c/ | cha /cʰ/ | ja /ɟ/ | jha /ɟʱ/ | ña /ɲ/ | ya /j/ | śa /ɕ/ | |||||||||

| Retroflex | ṭa /ʈ/ | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | ḍa /ɖ/ | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | ṇa /ɳ/ | ra /r/ | ṣa /ʂ/ | |||||||||

| Dental | ta /t̪/ | tha /t̪ʰ/ | da /d̪/ | dha /d̪ʱ/ | na /n/ | la /l/ | sa /s/ | |||||||||

| Labial | pa /p/ | pha /pʰ/ | ba /b/ | bha /bʱ/ | ma /m/ | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||||||||

In Unicode

The Unicode standard considers the Gupta script to be a stylistic variation of Brahmi, and thus Gupta texts are encoded using Brahmi Unicode characters.

| Brahmi[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1100x | 𑀀 | 𑀁 | 𑀂 | 𑀃 | 𑀄 | 𑀅 | 𑀆 | 𑀇 | 𑀈 | 𑀉 | 𑀊 | 𑀋 | 𑀌 | 𑀍 | 𑀎 | 𑀏 |

| U+1101x | 𑀐 | 𑀑 | 𑀒 | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 |

| U+1102x | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 |

| U+1103x | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 | 𑀴 | 𑀵 | 𑀶 | 𑀷 | 𑀸 | 𑀹 | 𑀺 | 𑀻 | 𑀼 | 𑀽 | 𑀾 | 𑀿 |

| U+1104x | 𑁀 | 𑁁 | 𑁂 | 𑁃 | 𑁄 | 𑁅 | 𑁆 | 𑁇 | 𑁈 | 𑁉 | 𑁊 | 𑁋 | 𑁌 | 𑁍 | ||

| U+1105x | 𑁒 | 𑁓 | 𑁔 | 𑁕 | 𑁖 | 𑁗 | 𑁘 | 𑁙 | 𑁚 | 𑁛 | 𑁜 | 𑁝 | 𑁞 | 𑁟 | ||

| U+1106x | 𑁠 | 𑁡 | 𑁢 | 𑁣 | 𑁤 | 𑁥 | 𑁦 | 𑁧 | 𑁨 | 𑁩 | 𑁪 | 𑁫 | 𑁬 | 𑁭 | 𑁮 | 𑁯 |

| U+1107x | 𑁰 | 𑁱 | 𑁲 | 𑁳 | 𑁴 | 𑁵 | BNJ | |||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Gupta numismatics

The study of Gupta coins began with the discovery of a hoard of gold coins in 1783. Many other such hoards have since been discovered, the most important being the Bayana (situated in Bharatpur district of Rajasthan) hoard, discovered in 1946, which contained more than 2000 gold coins issued by the Gupta Kings.[18] Many of the Gupta Empire's coins bear inscriptions of legends or mark historic events. In fact, it was one of the first Indian Empires to do so, probably as a result of its unprecedented prosperity.[7] Almost every Gupta king issued coins, beginning with its first king, Chandragupta I.

The scripts on the coin are also of a different nature compared to scripts on pillars, due to conservatism regarding the coins that were to be accepted as currency, which would have prevented regional variations in the script from manifesting on the coinage.[7] Moreover, space was more limited especially on their silver coins, and thus many of the symbols are truncated or stunted. An example is the symbol for /ta/ and /na/, which were often simplified to vertical strokes.

Gallery

The Allahabad pillar inscription of Samudragupta, with its standardised Gupta characters.

The Allahabad pillar inscription of Samudragupta, with its standardised Gupta characters. Brahmi and its descendent scripts.

Brahmi and its descendent scripts. The 5th- or 6th-century Gupta script Gopika Cave Inscription in Sanskrit about goddess Durga

The 5th- or 6th-century Gupta script Gopika Cave Inscription in Sanskrit about goddess Durga_141.jpg.webp) Gupta script decipheration table

Gupta script decipheration table

The name

The name

Śrī Yaśodharmma ("Lord Yashodharman") in Gupta script in Line 4 of the Mandsaur stone inscription of Yashodharman-Vishnuvardhana.[20]

Śrī Yaśodharmma ("Lord Yashodharman") in Gupta script in Line 4 of the Mandsaur stone inscription of Yashodharman-Vishnuvardhana.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy. p. 32.

- ↑ "Epigraphy, Indian Epigraphy Richard Salmon OUP" – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Handbook of Literacy in Akshara Orthography, R. Malatesha Joshi, Catherine McBride(2019),p.27

- ↑ Daniels, P. T. (January 2008), Writing systems of major and minor languages

- ↑ Masica, Colin (1993). The Indo-Aryan languages. p. 143.

- ↑ Sharma, Ram. 'Brahmi Script' . Delhi: BR Publishing Corp, 2002

- 1 2 3 Srivastava, Anupama. The Development of Imperial Gupta Brahmi Script. New Delhi: Ramanand, 1998

- ↑ Fischer, Steven Roger. A History of Writing. UK: Reaktion, 2004

- ↑ Evolutionary chart, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 7, 1838

- ↑ Fischer, Steven Roger (2004). History of Writing. Reaktion Books. p. 123. ISBN 9781861895882.

- ↑ Publishing, Britannica Educational (2010). The Culture of India. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 9781615302031.

- 1 2 3 "Gupta Unicode" (PDF).

- ↑ Das Buch der Schrift: Enthaltend die Schriftzeichen und Alphabete aller ... (in German). K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei. 1880. p. 126.

- ↑ The "h" (

) is an early variant of the Gupta script.

) is an early variant of the Gupta script. - ↑ Verma, Thakur Prasad (2018). The Imperial Maukharis: History of Imperial Maukharis of Kanauj and Harshavardhana (in Hindi). Notion Press. p. 264. ISBN 9781643248813.

- ↑ Sircar, D. C. (2008). Studies in Indian Coins. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 376. ISBN 9788120829732.

- ↑ Tandon, Pankaj (2013). Notes on the Evolution of Alchon Coins Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society, No. 216, Summer. Oriental Numismatic Society. pp. 24–34. also Coinindia Alchon Coins (for an exact description of this coin type)

- ↑ Bajpai, KD. 'Indian Numismatic Studies. ' New Delhi: Abhinav Publications 2004

- ↑ Puri, Baij Nath (1987). Buddhism in Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 187 Note 32. ISBN 9788120803725.

- ↑ Fleet, John Faithfull (1960). Inscriptions Of The Early Gupta Kings And Their Successors. pp. 150-158.

Further reading

- Carl Faulmann (1835–1894), Das Buch der Schrift, Druck und Verlag der Kaiserlichen Hof-und Staatsdruckerei, 1880

External links

- (in Spanish) The Gupta Alphabet

- AncientScripts.com entry on the Gupta Script

- Ye, Shao-Yong. (2009). An eastern variety of the post-Gupta script: Akṣara List of the Manuscripts of the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā and Buddhapālita's Commentary (ca. 550–650 CE). Research Institute of Sanskrit Manuscripts & Buddhist Literature, Peking University.