| Khom Thai | |

|---|---|

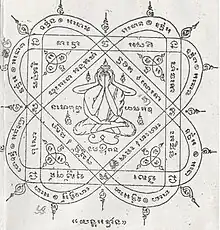

A Buddhist manuscript written in Khom Thai | |

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 1400 CE - present[1] |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages | Pali, Sanskrit, Khmer, Thai |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | Sukhothai, Lai Tay |

[a] The Semitic origin of the Brahmic scripts is not universally agreed upon. | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

The Khom script (Thai: อักษรขอม, romanized: akson khom, or later Thai: อักษรขอมไทย, romanized: akson khom thai; Lao: ອັກສອນຂອມ, romanized: Aksone Khom; Khmer: អក្សរខម, romanized: âksâr khâm) is a Brahmic script and a variant of the Khmer script used in Thailand and Laos,[2] which is used to write Pali, Sanskrit, Khmer and Thai.

Etymology

Historically, this script is known as Akson Khom (Khom Script, a variant of Khmer script) in Laos and Thailand.[3] The term khom (ขอม) means "Cambodia" or "Cambodian" and is used in historical chronicles; the modern term is khamen (เขมร).[4] Literally, the term "akson khom" means Khmer script.

History

The Thai adopted the ancient Khmer script as their official script around the 10th century, during the territorial expansion of the Khmer Empire, because the Thai language lacked a writing system at the time. The ancient Khmer script was not suitable for writing Thai, however, because of phonological differences between the Thai and Khmer languages.[5] Around the 15th century, the Thai added additional letterforms and letters to the script, to be able to write the Thai language. They called this new version of the Khmer script “Khom”, which means “Khmer” in Thai.[5] The knowledge of the Khom Thai script was, in the early periods of the Thai and Lao kingdoms, originally exclusive to the phraam. It is assumed that the phraam gained their knowledge from Khmer teachers or ancestors who came from Angkor. Later, the Khom Thai script spread from Central Thailand to neighboring regions including Nakhon Si Thammarat, to which many Thai phraam fled during and after the Burmese–Siamese wars.[6]

Punnothok (2006) indicated that the Khom Thai script has been used alongside the Thai script since the 15th century. The two scripts are used for different purposes, the Thai script is used for writing non-religious documents, while the Khom Thai script is mainly used for writing religious texts.[5] The Khom Thai script closely resembles the Aksar Mul script used in Cambodia, but some letters differ. The Khom Thai letterforms have not changed significantly since the Sukhothai era. The Khom Thai script was the most widely used of the ancient scripts found in Thailand.[7]

Use of the Khom Thai script has declined for three reasons. Firstly King Rama IV (1804–1868) ordered Thailand's Buddhist monks to use the Thai script when writing Pali, instead of Khom Thai.[8] Secondly, King Rama V (1853–1910) ordered the translation of the Tripiṭaka from Pali into Thai, using the Thai script. The third reason was the scrapping of the Khom Thai script from the Buddhist studies exam, the Sanam Luang test. In 1918, the Pali division of the Buddhist Association decided to again include an assignment about the Khom Thai script on the test, out of concern that the Khom Thai script would disappear. However, the Ministry of Education decided to cancel the Sanam Luang test permanently in 1945, on the basis of the government's nationalist and modernizing policies, which ended the study of the Khom Thai script at Buddhist institutes and schools and made it less necessary for monks and students to learn the Khom Thai script.[9] Tsumura (2009) pointed out that educational reforms in 1884 and 1921 were pivotal factors that worsened the situation for the Khom Thai script.[9] Since the national policies in that period focused on centralizing political power in Bangkok, the educational system tended to disregard traditional knowledge from outside of the capital, including the use of the Tham script, the Tai Noi script, and the Khom Thai script.[10]

Nowadays, the Khom Thai script is part of a required course for students of oriental palaeography in certain Thai universities including Silpakorn University. However, accessibility to information about the script is limited for ordinary Thais interested in the subject, and it receives little attention from the public in general.[11]

Usage

The script is used for various purposes such as Buddhist texts called Samut khoi, talismanic images, medicinal texts, magical textbooks, local Buddhist histories, treatises and manuals on topics like astrology, numerology, cosmology, warfare, sai-ja-saat, divination, and the creation and interpretation of yantras.[12]

Manuscripts employing the Khom Thai script can be found in the regions of Bangkok/Thonburi, Ayutthaya, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Champassak, Vientiane, parts of Isan, Luang Prabang, and Chiang Mai.[2] There are two main types of manuscripts that use the Khom Thai script, namely palm leaf manuscripts (Thai: ใบลาน, romanized: bai laan) and folding books (Thai: สมุดข่อย, romanized: samut khooi), the latter which were made of mulberry paper. A variety of other materials were also used.[13]

The Khom Thai script is considered a sacred script,[5] and its status is similar to the Siddhaṃ script used by Mahayana Buddhism. The script held a position of prestige at the Thai and Lao royal courts, similar to the Pali and Sanskrit languages and to a certain extent also the Khmer language, where the script was used in ritualised royal formula and formal protocols.[13]

Owing to the influence of Khmer occultism, it is common for Thai men to have their bodies ritualistically and symbolically marked with Khom Thai script— structured in various forms of “yantra”, called yantra tattooing.[14][15] The script is also used for yantras and mantras on cloth, paper, or engravings on brass plates in Cambodia and Thailand.[16][17]

The Khom Thai script on a Buddhist illustration

The Khom Thai script on a Buddhist illustration The Buddha legend written in the Khom Thai script - Ethnological Museum, Berlin

The Buddha legend written in the Khom Thai script - Ethnological Museum, Berlin The Suvannasama Jataka, in Pali language in the Khom Thai script

The Suvannasama Jataka, in Pali language in the Khom Thai script Thai Seal of the Royal Command: which reads "ព្រះបរម្មរាជឱង្ការ" (พฺระบรมฺมราชโองฺการ, royal command)

Thai Seal of the Royal Command: which reads "ព្រះបរម្មរាជឱង្ការ" (พฺระบรมฺมราชโองฺการ, royal command) Thai amulet or "Yantra" featuring the Khom Thai script

Thai amulet or "Yantra" featuring the Khom Thai script Pali manuscript from Thailand, written in Khom Thai script

Pali manuscript from Thailand, written in Khom Thai script

Characteristics

The Khom Thai script is written from left to right.[18] As the Khmer script does not contain tone symbols, some Thai vowels and tone symbols have been added to the Khom Thai script.[19]

The script is characterized by sharper serifs and angles than the Khmer script, and retainment of some antique characteristics, notably in the consonant kâ (ក).[17]

The Khom Thai script has subtypes and modifications like "Khoom Muul", "Khoom Chriang" and various others.[6]

Consonants

There are 35 full form letters in total, used for initial consonants. Most of these also have a subscribed form letter, which is used for word final consonants.[20]

| Velar |  ka ก |

kha ข |

ga ค |

gha ฆ |

ṅa ง |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alveolo-palatal |  ca จ |

cha ฉ |

ja ช |

jha ฌ |

ña ญ |

| Alveolar |  ṭa ฎ |

ṭha ฐ |

ḍa ฑ |

ḍha ฒ |

ṇa ณ |

ta ด |

tha ถ |

da ท |

dha ธ |

na น | |

| Labial |  pa บ |

pha ผ |

ba พ |

bha ภ |

ma ม |

| Fricative, liquid and guttural |  ya ย |

ra ร |

la ล |

va ว |

śa ศ |

ṣa ษ |

sa ส |

ha ห |

ḷa ฬ |

a อ |

Vowels

The Khom Thai script has two kind of vowels, namely, independent vowels that can be written alone, and dependent vowels that have to be combined with consonants to form words.[20] The dependent vowels are identical to their Thai counterparts.[21]

The following are eight independent vowels:

a อะ |

ā อา |

i อิ |

ī อี |

u อุ |

ū อู |

e เอ |

o โอ |

Tone marks

The tone marks of the Khom Thai script are identical to those of the Thai script.[21]

Numerals

The numerals used by the Khom Thai script resemble Thai and Khmer numerals, and feature long ascenders.[22]

Computerization

The Khom Thai script has not been included in Unicode, but Khom Thai fonts can be used with Thai encoding.

Farida Virunhaphol designed three Khom Thai fonts for teaching purposes. This set of fonts enables Thai users to become familiar with Khom Thai faster.[23]

References

- ↑ Virunhaphol 2017, pp. 154.

- 1 2 Igunma 2013, pp. 1.

- ↑ Igunma, Jana. "AKSOON KHOOM: Khmer Heritage in Thai and Lao Manuscript Cultures".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Haas, Mary R. (1964). Thai–English Student's Dictionary. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-8047-0567-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Virunhaphol 2017, pp. 22.

- 1 2 Igunma 2013, pp. 5.

- ↑ Virunhaphol 2017, pp. 155.

- ↑ Virunhaphol 2017, pp. 23.

- 1 2 Virunhaphol 2017, pp. 24.

- ↑ Virunhaphol 2017, pp. 25.

- ↑ Virunhaphol 2017, pp. 26.

- ↑ Igunma 2013, pp. 3.

- 1 2 Igunma 2013, pp. 2.

- ↑ Cadchumsang, Jaggapan (2011). People at the Rim: A Study of Tai Ethnicity and Nationalism in a Thai Border Village (Thesis). Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ↑ May, Angela Marie. (2014). Sak Yant: The Transition from Indic Yantras to Thai Magical Buddhist Tattoos (Master's thesis) (p. 6). The University of Alabama at Birmingham.

- ↑ Igunma 2013, pp. 4.

- 1 2 Tsumura, Fumihiko (2009). "Magical Use of Traditional Scripts in Northeastern Thai Villages. Senri Ethnological Studies, 74": 63–77.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "ประวัติอักษรขอมไทย". Archived from the original on 2017-07-15. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- ↑ "Buddhist Texts, Including the Legend of Phra Malai, with Illustrations of The Ten Birth Tales". Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- 1 2 Virunhaphol 2017, pp. 106.

- 1 2 Virunhaphol 2017, pp. 136.

- ↑ Virunhaphol 2017, pp. 133.

- ↑ Virunhaphol 2017, pp. 111.

Sources

- Virunhaphol, Farida (2017). "Designing Khom Thai Letterforms for Accessibility (Doctoral dissertation). University of Huddersfield" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Igunma, Jana (2013). "Aksoon Khoom: Khmer Heritage in Thai and Lao Manuscript Cultures. Tai Culture, 23: Route of the Roots: Tai-Asiatic Cultural Interaction".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)