| Sasak | |

|---|---|

| Base Sasak Basâ Sasak | |

| Native to | Indonesia |

| Region | Lombok |

| Ethnicity | Sasak |

Native speakers | 2.7 million (2010)[1] |

| Balinese (modified),[2] Latin[3] | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | sas |

| ISO 639-3 | sas |

| Glottolog | sasa1249 |

| ELP | Sasak |

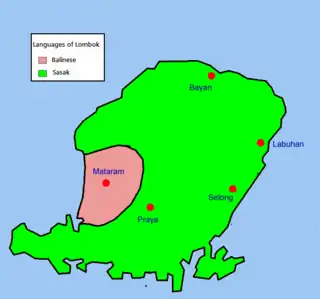

Linguistic map of Lombok, based on 1981 data. Areas with Sasak speakers are shown in green, and Balinese speakers in red. | |

The Sasak language (base Sasak or basâ Sasak) is spoken by the Sasak ethnic group, which make up the majority of the population of Lombok, an island in Indonesia. It is closely related to the Balinese and Sumbawa languages spoken on adjacent islands, and is part of the Austronesian language family. Sasak has no official status; the national language, Indonesian, is the official and literary language in areas where Sasak is spoken.

Some of its dialects, which correspond to regions of Lombok, have a low mutual intelligibility. Sasak has a system of speech levels in which different words are used depending on the social level of the addressee relative to the speaker, similar to neighbouring Javanese and Balinese.

Not widely read or written today, Sasak is used in traditional texts written on dried lontar leaves and read on ceremonial occasions. Traditionally, Sasak's writing system is nearly identical to Balinese script.

Speakers

Sasak is spoken by the Sasak people on the island of Lombok in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia, which is located between the island of Bali (on the west) and Sumbawa (on the east). Its speakers numbered about 2.7 million in 2010, roughly 85 percent of Lombok's population.[1] Sasak is used in families and villages, but has no formal status. The national language, Indonesian, is the language of education, government, literacy and inter-ethnic communication.[4] The Sasak are not the only ethnic group in Lombok; about 300,000 Balinese people live primarily in the western part of the island and near Mataram, the provincial capital of West Nusa Tenggara.[5] In urban areas with more ethnic diversity there is some language shift towards Indonesian, mainly in the forms of code-switching and mixing rather than an abandoning of Sasak.[4]

Classification and related languages

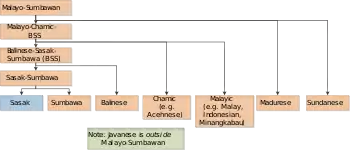

Austronesian linguist K. Alexander Adelaar classified Sasak as one of the Malayo-Sumbawan languages group (a group he first identified) of the western Malayo-Polynesian family in a 2005 paper.[6][7] Sasak's closest sister language is Sumbawa and, with Balinese, they form the Balinese-Sasak-Sumbawa (BSS) subgroup.[6] BSS, Malayic (which includes Malay, Indonesian and Minangkabau) and Chamic (which includes Acehnese) form one branch of the Malayo-Sumbawan group.[7][6] The two other branches are Sundanese and Madurese.[7] This classification puts Javanese, previously thought to belong to the same group, outside the Malayo-Sumbawan group in a different branch of the western Malayo-Polynesian family.[7]

The Malayo-Sumbawan proposal, however, is rejected by Blust (2010) and Smith (2017), who included the BSS languages in the putative "Western Indonesian" subgroup, alongside Javanese, Madurese, Sundanese, Lampung, Greater Barito and Greater North Borneo languages.[8][9]

Kawi, a literary language based on Old Javanese, has significantly influenced Sasak.[10] It is used in Sasak puppet theatre, poetry and some lontar-based texts, sometimes mixed with Sasak.[10][2] Kawi is also used for hyperpoliteness (a speech level above Sasak's "high" level), especially by the upper class known as the mènak.[10]

Phonology

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | tɕ | k | ʔ |

| voiced | b | d | dʑ | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | s | h | ||||

| Rhotic | ɾ~r | |||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||

Eight vowels appear in Sasak dialects,[12] contrasting with each other differently by dialect.[12] They are represented in Latin orthography by ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩ and ⟨u⟩, with diacritics sometimes used to distinguish conflated sounds.[12][13] The usual Indonesian practice is to use ⟨e⟩ for the schwa, ⟨é⟩ for the close-mid front vowel, ⟨è⟩ for the open-mid front vowel, ⟨ó⟩ for the close-mid back vowel and ⟨ò⟩ for the open-mid back vowel.[13]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Close-Mid | e | ə | o |

| Open-Mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Open | a |

Diphthongs

Sasak has the diphthongs (two vowels combined in the same syllable) /ae/, /ai/, /au/, /ia/, /uə/ and /oe/.[14]

Morphophonology

Sasak words have a single stress on the final syllable.[15] Final /a/ in Sasak roots change phonetically to a tense [ə] (mid central vowel); for example, /baca/ ('to read') will be realized (and spelled) as bace, but when affixed the vowel stays the same, as in bacaan, 'reading' and pembacaan, 'reading instrument'.[16] In compounding, if the first element ends in a vowel, the element will take a nasal linker (/n/ in most dialects, /ŋ/ in some). For example, compounding mate ('eye') and bulu ('hair') will result in maten bulu ('eyelash').[15]

Grammar

Sasak has a flexible word order, typical of Indonesian western Austronesian (WAN) languages.[17] Frequency distributions of the various word orders are influenced by the verb forms in the clause (i.e. whether the clause involves a nasal or an unmarked verb, see #Verbs).[17] Clauses involving the nasal verb form are predominantly subject-verb-object (SVO), similar to actor-focus classes in other Indonesian WAN languages.[17] In contrast, clauses with an unmarked verb form do not have a dominant word order; three of the six possible orders (subject-verb-object, verb-subject-object and object-verb-subject) occur with roughly-equal frequency.[18]

Verbs, like those of other western Indonesian languages, are not conjugated for tense, mood or aspect. All affixes are derivational.[19] Verbs may appear in two forms: unmarked (also known as basic or oral) and nasal.[20][13] The basic form appears in vocabulary lists and dictionaries,[13] and the nasal form adds the nasal prefix n-.[20] The nasal prefix, which also appears as nge-, m- and other forms, may delete the first consonant of the basic form.[20][21] For example, the unmarked form of 'to buy' is beli and the nasal form is mbeli.[21] The nasal prefix can also turn a noun into the corresponding verb; for example, kupi ('coffee') becomes ngupi ('to drink coffee').[19] The function of the prefix and nasal derivations from the basic form differ by dialect.[22] For example, eastern dialects of Sasak have three types of nasalization: the first marks transitive verbs, the second is used for predicate focus, and the third is for a durative action with a non-specific patient.[23] Imperative and hortative sentences use the basic form.[13]

Sasak has a variety of clitics, a grammatical unit pronounced as part of a word (like an affix) but a separate word syntactically—similar to the English language clitic 'll.[24] Simple clitics occur in a demonstrative specifier attached to a previous noun or noun phrase; for example, ni ('this') in dengan ni ('this person').[25][26] Special clitics occur with noun hosts to encode inalienable possession, and with other hosts to encode agents and patients.[26] For example, the possessive clitic ku (or kò or k, depending on dialect)—which means 'my' and corresponds to the pronoun aku ('I')—can attach to the noun ime ('hand') for imengku ('my hand').[16]

Variations

Regional

Sasak has significant regional variations, including by phonology, vocabulary and grammar.[4] Native speakers recognize five labelled dialects, named for how "like that" and "like this" are pronounced: Kutó-Kuté (predominant in North Sasak), Nggetó-Nggeté (Northeast Sasak), Menó-Mené (Central Sasak), Ngenó-Ngené (Central East Sasak, Central West Sasak) and Meriaq-Meriku (Central South Sasak).[1][3] However, linguist Peter K. Austin said that the five labels do not "reflect fully the extensive geographical variation ... found within Sasak" in many linguistic areas.[1] Some dialects have a low mutual intelligibility.[3]

Speech levels

Sasak has a system of speech levels in which different words are used, depending on the social level of the addressee relative to the speaker.[1] The system is similar to that of Balinese and Javanese (languages spoken on neighbouring islands)[4] and Korean.[27] There are three levels in Sasak for the status of the addressee (low, mid- and high),[1] and a humble-honorific dimension which notes the relationship between the speaker and another referent.[28] For example, 'you' may be expressed as kamu (low-level), side (mid-), pelinggih (high) or dekaji (honorific).[29] 'To eat' is mangan (low), bekelór (mid-), madaran (high) or majengan (honorific).[29]

All forms except low are known as alus ('smooth' or 'polite') in Sasak.[4] They are used in formal contexts and with social superiors, especially in situations involving mènak (the traditional upper caste, which makes up eight percent of the population).[4] The system is observed in regional varieties of the language. Although low-level terms have large regional variations, non-low forms are consistent in all varieties.[29] According to Indonesian languages specialist Bernd Nothofer, the system is borrowed from Balinese or Javanese.[10]

Literature

The Sasak have a tradition of writing on dried leaves of the lontar palm.[10] The Javanese Hindu-Buddhist Majapahit empire, whose sphere of influence included Lombok, probably introduced literacy to the island during the fourteenth century.[30] The oldest surviving lontar texts date to the nineteenth century; many were collected by the Dutch and kept in libraries in Leiden or Bali.[10] The Mataram Museum in Lombok also has a collection, and many individuals and families on the island keep them as heirlooms to be passed from generation to generation.[10]

The lontar texts are still read today in performances known as pepaòsan.[31] Readings are made for a number of occasions, including funerals, weddings and circumcision ceremonies.[31] Rural Sasak read the lontar texts as part of a ritual to ensure the fertility of their farm animals.[31] Peter K. Austin described a pepaòsan which was performed as part of a circumcision ceremony in 2002,[32] with paper copies of lontar texts rather than palm leaves.[33]

Lombok's lontar texts are written in Sasak, Kawi (a literary language based on old Javanese) or a combination of the two.[2] They are written in hanacaraka, a script nearly identical to Balinese.[2] Its basic letters consist of a consonant plus the vowel a.[2] The first five letters read ha, na, ca, ra and ka, giving the script its name.[2] Syllables with vowels other than a use the basic letter plus diacritics above, below or around it.[2] Final consonants of a syllable or consonant clusters may also be encoded.[2]

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Austin 2012, p. 231.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Austin 2010, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 Sasak language at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Austin 2010, p. 33.

- ↑ Austin 2010, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 Shibatani 2008, p. 869.

- 1 2 3 4 Adelaar 2005, p. 357.

- ↑ Blust 2010, p. 81-82.

- ↑ Smith 2017, p. 443, 456.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Austin 2010, p. 35.

- ↑ Archangeli, Tanashur & Yip (2020).

- 1 2 3 4 Seifart 2006, p. 294.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Austin 2012, p. 232.

- ↑ PHOIBLE 2014.

- 1 2 Austin 2004, p. 4.

- 1 2 Austin 2004, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Wouk 1999, p. 98.

- ↑ Wouk 1999, p. 99.

- 1 2 Austin 2013, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Wouk 1999, p. 93.

- 1 2 Austin 2013, p. 33.

- ↑ Austin 2013, p. 43.

- ↑ Austin 2013, p. 43-44.

- ↑ Austin 2004, p. 2-3.

- ↑ Austin 2004, p. 6.

- 1 2 Austin 2004, p. 18.

- ↑ Goddard 2005, p. 215.

- ↑ Austin 2012, p. 231-232.

- 1 2 3 Austin 2010, p. 34.

- ↑ Austin 2010, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Austin 2010, p. 39.

- ↑ Austin 2010, p. 42.

- ↑ Austin 2010, p. 44.

Bibliography

- Adelaar, Alexander (2005). "Malayo-Sumbawan". Oceanic Linguistics. 44 (2): 356–388. doi:10.1353/ol.2005.0027. JSTOR 3623345. S2CID 246237112.

- Archangeli, Diana; Tanashur, Panji; Yip, Jonathan (2020). "Sasak, Meno-Mené Dialect". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 50 (1): 93–108. doi:10.1017/S0025100318000063. S2CID 150248301.

- Austin, Peter K. (2004). Clitics in Sasak, Eastern Indonesia. Linguistics Association of Great Britain Annual Conference. Sheffield, United Kingdom.

- Austin, Peter K. (2010). "Reading the Lontars: Endangered Literature Practices of Lombok, Eastern Indonesia". Language Documentation and Description. 8: 27–48.

- Austin, Peter K. (2012). "Tense, Aspect, Mood and Evidentiality in Sasak, Eastern Indonesia". Language Documentation and Description. 11: 231–251.

- Austin, Peter K. (2013). "Too Many Nasal Verbs: Dialect Variation in the Voice System of Sasak". NUSA: Linguistic Studies of Languages in and Around Indonesia. 54: 29–46. hdl:10108/71804.

- Blust, Robert (2010). "The Greater North Borneo Hypothesis". Oceanic Linguistics. 49 (1): 44–118. doi:10.1353/ol.0.0060. JSTOR 40783586. S2CID 145459318.

- Donohue, Mark (2007). "The Papuan Language of Tambora". Oceanic Linguistics. 46 (2): 520–537. doi:10.1353/ol.2008.0014. JSTOR 20172326. S2CID 26310439.

- Goddard, Cliff (2005). The Languages of East and Southeast Asia: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927311-9.

- PHOIBLE (2014). "Sasak Sound Inventory (PH)". In Steven Moran; Daniel McCloy; Richard Wright (eds.). PHOIBLE Online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- Seifart, Frank (2006). "Orthography Development". In Jost Gippert; Nikolaus P. Himmelmann; Ulrike Mosel (eds.). Essentials of Language Documentation. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 275–300. ISBN 9783110197730.

- Shibatani, Masayoshi (2008). "Relativization in Sasak and Sumbawa, Eastern Indonesia" (PDF). Language and Linguistics. 9 (4): 865–916.

- Smith, Alexander D. (2017). "The Western Malayo-Polynesian Problem". Oceanic Linguistics. 56 (2): 435–490. doi:10.1353/ol.2017.0021. JSTOR 26408513. S2CID 149377092.

- Wouk, Fay (1999). "Sasak Is Different: A Discourse Perspective on Voice". Oceanic Linguistics. 38 (1): 91–114. doi:10.2307/3623394. JSTOR 3623394.

External links

- Online Dictionary Sasak language - English

- David Goldsworthy's collection of Music of Indonesia and Malaysia archived with Paradisec includes open access recordings in Sasak.