| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

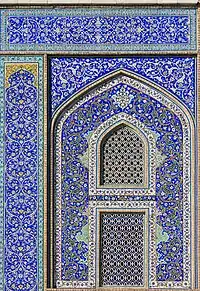

A sahn (Arabic: صَحْن, ṣaḥn), is a courtyard in Islamic architecture, especially the formal courtyard of a mosque.[1][2][3] Most traditional mosques have a large central sahn, which is surrounded by a riwaq or arcade on all sides. In traditional Islamic design, residences and neighborhoods can have private sahn courtyards.

The sahn is a common element in religious buildings and residences throughout the Muslim world, used in urban and rural settings. The cloister is its equivalent in European medieval architecture and its religious buildings.

Etymology

History

Originally, the sahn was used for dwellings, as a secure and private setting within a residence compound's walls. Ruins of houses in Sumerian Ur with sahns have been found, from the Third Dynasty of Ur (2100–2000 BCE).

Most mosque courtyards (sahn) contained a public fountain where Muslims performed Wudu a ritual purification required before prayer.[5] The Great Umayyad Mosque of Damascus built in 706 CE[6] provides one of the earliest withstanding example of a Sahn. The 122.5 meter long and 50 meter wide rectangular courtyard of the mosque is surrounded by a colonnaded portico (riwaq) on three sides.[7]

The use of sahn in Islamic architecture continued until the mid-twentieth century, when Modern architecture began to influence Islamic cultures' residential and public buildings' designs.

Types

Mosque design

Almost every historic or traditional mosque has a sahn. The use of it in Middle Eastern countries' mosques was carried on to most Islamic countries' mosque architecture.

Traditional mosque sahns are surrounded by the riwaq arcade on all sides. They also contain fountain water basins, such as a howz, for ritual purification cleansing and performing of wudu (Islamic ablutions), and flowing fountains for drinking water.

The inner courtyard is not a religiously proscribed architectural feature, and some mosques, especially since the twentieth century, do not have a sahn.

Residential design

Residential sahns, part of a courtyard house, are the most private. The scale and design details differ: from urban to rural locales; different regions and climates, and different eras and cultures – but the basic function of security and privacy remain the same. The sahn can be a private garden, a service yard, and a summer season outdoor living room for the family or entertaining.

Usually the main entrance of the house does not lead directly to the sahn. It is reached through a broken or curved corridor called a majaz (Arabic: مجاز, mağāz). This lets residents admit guests into the majlis (Arabic: مجلس, mağlis), a salon or reception room, without seeing into the sahn. It is then a protected and proscribed place where the women of the house need not be covered in the hijab clothing traditionally necessary in public.

In urban settings, the sahn is usually surrounded by a colonnaded riwaq, and has a howz, or pool of water, in the middle. The residence's iwan, a private family room veranda of three walls, usually overlooks the sahn and gives direct or stairway access to it. Upper floor rooms may also view it through mashrabiyas, wooden lattice covered windows.

The Moorish patios of al-Andalus, in present-day Spain, include World Heritage Sites such as the Court of the Lions and Court of the Myrtles at the Alhambra palace.

Urban design

- Private

Traditional Islamic neighborhoods can have a dedicated central open space, a communally private sahn, called saha (Arabic: ساحة, sāḥä), only for the neighbourhood's residents, usually consisting of members of the same tribe.

- Public

The idea of public open space, central in the middle of a city, a town square or central plaza, is part of historical and contemporary urban design in many cultures around the world. Ancient examples are the Greek agora and Roman forum. They can provide a place for various civic uses such as public gatherings, celebrations, and protests, open air markets and festivals, and transportation links.

See also

- durqāʿa: central space in a building

- Index: Islamic architectural elements

References

- ↑ M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Mosque". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ↑ Petersen, Andrew (1996). Dictionary of Islamic architecture. Routledge. p. 247. ISBN 9781134613663.

- ↑ "The Mosque". metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ Bandyopadhyay, Soumyen; Sibley, Magda (July 2002). "The Distinctive Typology of Central Omani Mosques: Its Nature and Antecedents". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 33 (33): 99–116. JSTOR 41223756. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ↑ "The Mosque". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ↑ Grafman and Rosen-Ayalon, 1999, p. 7.

- ↑ "Umayyad Mosque". Museum With No Frontiers. Retrieved 5 March 2021.