A sitara or sitarah (Arabic: سِتَارَة [si.taː.ra] ⓘ) is an ornamental curtain used in the sacred sites of Islam. A sitara forms part of the kiswah, the cloth covering of the Kaaba in Mecca. Another sitara adorns the Prophet's Tomb in the Al-Masjid an-Nabawi mosque in Medina. These textiles bear embroidered inscriptions of verses from the Quran and other significant texts. Sitaras have been created annually since the 16th century as part of a set of textiles sent to Mecca. The tradition is that the textiles are provided by the ruler responsible for the holy sites. In different eras, this has meant the Mamluk Sultans, the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire, and presently the rulers of Saudi Arabia.[1] The construction of the sitaras is both an act of religious devotion and a demonstration of the wealth of the rulers who commission them.[2]

Textiles of the Islamic holy sites

The earliest recorded sitara was made in Egypt in 1544, during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent.[3] Suleiman set aside the revenue of ten villages to fund the creation of textiles for the Kaaba and the Prophet's Mosque: an arrangement that continued until 1813.[4] Replacing the textiles is one of the privileges of the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, a title adopted by Mamluk, Ottoman, and Saudi Arabian rulers.[5]

Sitaras for the Kaaba were part of a set of textiles made annually at a dedicated workshop in Cairo, the Dar al-Kiswa, until 1927 when the king Ibn Saud established a workshop in Mecca.[6][3] At the start of the 20th century, the Cairo workshop employed more than a hundred artists and textile workers.[4] Responsibility for transporting the textiles from Cairo to Mecca was given to a specially chosen Muslim family, for whom it was a high honour.[6] The textiles were usually cut up and distributed once replaced. Ottoman royals and dignitaries would convert the pieces to clothing or tomb coverings.[3]

Textiles of the Great Mosque

The Kaaba, situated in the Great Mosque of Mecca, is the most holy site in Islam.[7] It is the qibla, the point that Muslims face towards while praying.[7] The Five Pillars of Islam include the hajj, a pilgrimage to Islam's holiest sites. One of the rites of the hajj is the tawaf which involves walking seven times around the Kaaba.[8]

The textile coverings of the Kaaba are among the most sacred objects in Islamic art.[5] A sitara, on average 5.75 metres (18.9 ft) by 3.5 metres (11 ft), covers the door of the Kaaba and forms part of the kiswah: the textile covering of the building.[5] This is assembled by sewing together four separate textile panels.[4] This sitara is also known as the burqu'.[3] A smaller sitara covers an internal door of the Kaaba, the Bab al-Tawba.[5] Being protected from weathering, this internal sitara is replaced much less frequently.[5] The tradition is also more recent; the earliest documented internal sitara was in 1893.[5] The Maqam Ibrahim (Station of Abraham) is a small square stone near the Kaaba which, according to Islamic tradition, bears the footprint of Abraham.[9] It used to be housed in a structure with its own sitara that was replaced annually.[4] The minbar (pulpit) within the Great Mosque has its own sitara.[4]

Having been in contact with the holiest site of Islam, the textiles are regarded as infused with barakah (blessings).[1] After use, they are usually split into parts to be given to dignitaries or pilgrims. Fragments of recent kiswahs adorn many of Saudi Arabia's government buildings and embassies.[6]

Sitaras of the Prophet's Tomb

The tradition of the Sultan sending a sitara to cover the Prophet's Tomb began in the 10th century.[10] A white sitara was provided for the tomb in the 12th century by the Fatimids.[11] Being away from direct sunlight, the Medina textiles have been replaced less frequently than the Kaaba textiles; in the 15th century, this was every six or seven years as the fabric wore out.[12]

Decoration

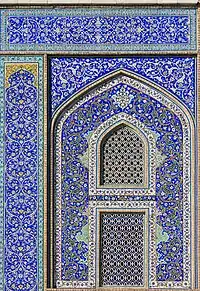

The basic designs of the sitara were established in the 16th century and continue to the present.[3] The colours used have changed in different eras. The present colour scheme for the sitara of the Kaaba, in use since the early 20th century, is gold and white embroidery on a black background.[13]

The inscriptions embroidered in gold and silver wire have become more ornate over time.[3] These inscriptions include verses from the Quran and supplications to Allah, as well as the names of the rulers who commissioned the textiles.[13][4] Sitaras made in the Ottoman Empire included the Sultan's tughra (their official calligraphed monogram) in their design.[10] The shahada (the Islamic declaration of faith) is another text used repeatedly.[1] Sitaras for the Kaaba were traditionally decorated with gold buttons and tassels.[4]

Surviving examples

Although they are usually divided into parts after use, rare examples of complete sitaras exist in some collections.[5] These collections include the Khalili Collection of Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage,[14] the British Museum, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met).[5][15] During the Ottoman era, many sacred textiles, including some sitaras, were returned to Istanbul after use, now forming part of the collection of the Topkapı Palace.[1] Among the Khalili collection's sitaras is one from the Kaaba, 499 centimetres (196 in) high, dating from 1606. Made in Cairo, it was commissioned by Ahmed I.[16][17] Others, similarly embroidered with multiple verses from the Quran, were commissioned by Abdülmejid I[18][19] and Mahmud II.[20] This collection also includes several sitaras for the Prophet's Mosque, from the 18th century onwards.[21] One in red silk, 280 centimetres (110 in) high, was made in Istanbul in the early 19th century. It bears the cartouche of Mahmud II who commissioned it for the Rawḍah ash-Sharifah (Noble Garden) of the mosque.[22][23] The Met's sitara was commissioned by Abdul Hamid II for the interior door of the Kaaba and is 280 centimetres (110 in) high. It is dated 1315 AH (1897–98 AD) and calls for blessings for Abbas II of Egypt, who would have overseen the textile's production.[15]

An 18th century sitara, commissioned by Selim III for the Prophet's Mosque, was donated to the Ashmolean Museum by Nasser Khalili in 2012.[24][2] Khalili also donated two sitaras made for the Prophet's Mosque to the British Museum in 2012. One is dated AH 1204 (1789–1790 AD) and bears the name of Selim III.[25] The other was commissioned by Mahmud II in the early 18th century and bears his tughra.[26] The Sharjah Museum of Islamic Civilisation includes a sitara from the door of the Kaaba from 1985.[27] The Museum of Turkish Calligraphy Art in Istanbul has a complete kiswah.[1] In 1983 the Saudi Arabian government donated a sitara from the Kaaba to the headquarters of the United Nations, where it remains on display.[6]

Sitara for the Prophet’s Mosque, made in Istanbul, dated 1298 AH (1880–81 AD)

Sitara for the Prophet’s Mosque, made in Istanbul, dated 1298 AH (1880–81 AD) Sitara for the Internal Door of the Kaaba, made in Cairo, early 20th century

Sitara for the Internal Door of the Kaaba, made in Cairo, early 20th century

See also

Media related to Sitaras (textiles) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sitaras (textiles) at Wikimedia Commons

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ipek, Selin (Summer 2011). "Dressing the Prophet: Textiles from the Haramayn". Hali. 168: 49–51. ISSN 0142-0798.

- 1 2 "Sitarah made for the Mosque of the Prophet in Medina". Yousef Jameel Centre for Islamic and Asian Art. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Porter, Venetia (2012). "Textiles of Mecca and Medina". In Porter, Venetia (ed.). Hajj : journey to the heart of Islam. Cambridge, Mass.: The British Museum. pp. 257–265. ISBN 978-0-674-06218-4. OCLC 709670348.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Nassar, Nahla (2013). "Dar al-Kiswa al-Sharifa: Administration and Production". In Porter, Venetia; Saif, Liana (eds.). The Hajj : collected essays. London: The British Museum. pp. 176–178. ISBN 978-0-86159-193-0. OCLC 857109543.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kern, Karen M.; Rosenfield, Yael; Carò, Federico; Shibayama, Nobuko (December 2017). "The Sacred and the Modern: The History, Conservation, and Science of the Madina Sitara". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 52: 72–93. doi:10.1086/696548. ISSN 0077-8958. S2CID 194836803.

- 1 2 3 4 Vincent-Barwood, Aileen (September–October 1985). "A Gift from the Kingdom". Saudi Aramco World. 36 (5). Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- 1 2 Wensinck, Arent Jan (1978). "Kaʿba". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume IV: Iran–Kha (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 317–322. OCLC 758278456.

- ↑ Ruqaiyyah Maqsood (1994), World Faiths, teach yourself – Islam, p. 76, ISBN 0-340-60901-X

- ↑ Peters, F. E. (1994). "Another Stone: The Maqam Ibrahim". The Hajj. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9780691026190.

- 1 2 Burge, Stephen (2020). The Prophet Muhammad: Islam and the Divine Message. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-83860-659-6.

- ↑ McGregor, Richard J. A. (2020). Islam and the Devotional Object. Cambridge University Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-1-108-48384-1.

- ↑ al-Mojan, Mohammed H. (2013). "The Textiles made for the Prophet's Mosque at Medina". In Porter, Venetia; Saif, Liana (eds.). The Hajj : collected essays. London: The British Museum. pp. 184–194. ISBN 978-0-86159-193-0. OCLC 857109543.

- 1 2 Ghazal, Rym (28 August 2014). "Woven with devotion: the sacred Islamic textiles of the Kaaba". The National. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ↑ "Sitarah". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- 1 2 "Sitara, Interior Door Curtain of the Ka'ba: dated A.H. 1315/A.D. 1897–98". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- ↑ Nassar, Nahla (2020). "Curtain for the door of the Ka'ba, with the name of Sultan Ahmed I". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- ↑ "Curtain for Door of the Ka'bah". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- ↑ "Curtain for the Door of the Ka'bah". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

- ↑ Nassar, Nahla (2020). "Curtain for the door of the Ka'ba, with the name of Sultan Abdülmecid ['Abd al-Majid] I". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

- ↑ "Sitarah for the Door of the Ka'aba". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

- ↑ "Hajj and The Arts of Pilgrimage". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2021-01-14.

- ↑ "Sitarah for the Rawdah of the Prophet's Mosque in Medina". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- ↑ Nassar, Nahla (2020). "Sitara for the rawda of the Prophet's mosque in Medina". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- ↑ Artdaily. "Important textile from the prophet Muhammad's tomb donated to the Ashmolean Museum". artdaily.cc. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- ↑ "curtain; hanging". The British Museum. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- ↑ "curtain; hanging". The British Museum. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- ↑ "Curtain for the door of the Holy Ka'ba in Makkah al-Mukarramah". Explore Islamic Art Collections. 2021. Retrieved 2021-03-11.

- ↑ Rogers, J. M. (2008). The arts of Islam : treasures from the Nasser D. Khalili collection (Revised and expanded ed.). Abu Dhabi: Tourism Development & Investment Company (TDIC). p. 345. OCLC 455121277.

.jpeg.webp)