| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Zinc antimonide | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.031.708 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| UN number | 1459 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| ZnSb, Zn3Sb2, Zn4Sb3 | |

| Molar mass | 434.06 g/mol |

| Appearance | silver-white orthorhombic crystals |

| Density | 6.33 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 546 °C (1,015 °F; 819 K) (565 °C, 563 °C) |

| reacts | |

| Band gap | 0.56 eV (ZnSb), 1.2eV (Zn4Sb3) |

| Structure | |

| Orthorhombic, oP16 | |

| Pbca, No. 61 | |

| Hazards | |

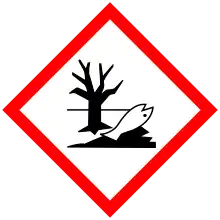

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H302, H331, H410 | |

| P261, P273, P311, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Zinc antimonide (ZnSb), (Zn3Sb2), (Zn4Sb3) is an inorganic chemical compound. The Zn-Sb system contains six intermetallics.[2] Like indium antimonide, aluminium antimonide, and gallium antimonide, it is a semiconducting intermetallic compound. It is used in transistors, infrared detectors and thermal imagers, as well as magnetoresistive devices.

History of zinc–antimony alloys and zinc antimonide

The first reported use of zinc-antimony alloys was in the original work of T. J. Seebeck on thermoelectricity,[3] a scientist who would then give his name to the Seebeck effect. By the 1860s, Moses G. Farmer, an American inventor, had developed the first high powered thermoelectric generator based on using a zinc-antimony alloy with a composition very close to stoichiometric ZnSb. He showed this generator at the 1867 Paris Exposition where it was carefully studied and copied (with minor modifications) by a number of people including Clamond. Farmer finally received the patent on his generator in 1870. George H. Cove patented a thermoelectric generator based on a Zn-Sb alloy in the early 1900s. His patent [4] claimed that the voltage and current for six "joints" was 3V at 3A. This was a far higher output than would be expected from a thermoelectric couple, and was possibly the first demonstration of the thermophotovoltaic effect, as the bandgap for ZnSb is 0.56eV, which under ideal conditions could yield close to 0.5V per diode. The next researcher to work with the material was Mária Telkes while she was at Westinghouse in Pittsburgh during the 1930s. Interest was revived again with the discovery of the higher bandgap Zn4Sb3 material in the 1990s.

References

- ↑ Lide, David R. (1998), Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87 ed.), Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, pp. 4–95, ISBN 0-8493-0594-2

- ↑ Li, Jing-Bo; Record, Marie-Christine; Tedenac, Jean-Claude (2007). "A thermodynamic assessment of the Sb-Zn system". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 438 (1–2): 171–177. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2006.08.035.

- ↑ Seebeck (1822). "Magnetische Polarisation der Metalle und Erze durch Temperatur-Differenz" [Magnetic polarization of metals and ores by temperature differences]. Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin (in German): 265–373.

- ↑ Cove (1906). "THERMOELECTRIC BATTERY AND APPARATUS" (PDF).