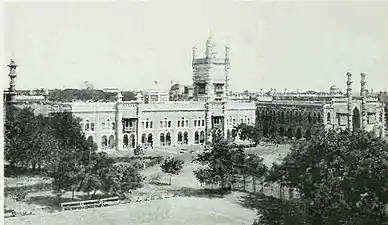

| Chepauk Palace | |

|---|---|

Chepauk Palace, c. 2006 | |

| General information | |

| Type | Palace |

| Architectural style | Indo-Saracenic architecture |

| Location | Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India |

| Completed | 1768 |

Chepauk Palace was the official residence of the Nawab of Arcot from 1768 to 1855. It is situated in the neighbourhood of Chepauk in Chennai, India and is constructed in the Indo-Saracenic style of architecture.

History

After the Carnatic Wars Nawab Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah of the Carnatic Sultanate, an ally of the British and was dependent on Company troops for his protection. So, in 1764, he thought of constructing a palace for himself within the ramparts of Fort St George.[1] However, due to space constraints, Wallajah was forced to abandon his plans and instead constructed a palace at Chepauk, a few miles to the south of the fort.[1]

Known for its intricate carvings, wide arches, red brick walls and lime mortar, Chepauk Palace was built by the engineer Paul Benfield, who completed it in 1768. It was one of the first buildings in India to be built in the Indo-Saracenic style. According to historian S. Muthiah: "Paul Benfield, an East India Company engineer turned contractor, made buildings to last, a reputation that made him rich."[2]

When the principality of Carnatic was abolished in 1855 as per the Doctrine of Lapse, the Chepauk Palace was brought to auction to pay off the Nawab's debts and was eventually purchased by the Madras government.[3] The palace functioned as the office of the revenue board and the Public Works Department (PWD) Secretariat.[3]

The palace comprises two blocks, namely, Kalas Mahal and Humayun Mahal. Kalas Mahal was the official residence of the Nawabs from 1768 to 1855.[4] Humayun Mahal, the northern block, was virtually rebuilt between 1868 and 1871 by Robert Chisholm when assigned the work of creating a new records office and building for the Revenue Board by Governor Lord Napier.[5][6]

Originally Humayun Mahal had been single story[6] with the Diwan-e-Khana Durbar Hall[2] in its middle over which there was a dome. To transform Humayun Mahal, Chisholm removed the tower, added a first floor and Madras terraced roof. He also added a facade that matched the Khalsa Mahal, which can be seen from the Wallajah Road. To compensate for removing the dome he also added a new eastern entrance, also in the style of the Khalsa Mahal, that faces the beach. Rather than being part of the Humayun Mahal, this new entrance was built as a square block in front of the Mahal and was called the Records Office.[6]

In 1859, the former Survey School became the Civil Engineering College and moved into part of Kalasa Mahal.[7]: 246 The college was renamed College of Engineering in 1861.[8] In 1862 the accommodation for the college was extended to a part of the lower floor and the whole of the upper floor. The Government Carnatic Agent occupied the remainder of the lower floor.[7]: 247

Chepauk Palace in Chennai, c. 1905

Chepauk Palace in Chennai, c. 1905.jpg.webp) Chepauk Palace, Madras - Tucks Oilette (1907)[9]

Chepauk Palace, Madras - Tucks Oilette (1907)[9] A panoramic view of Chepauk Palace

A panoramic view of Chepauk Palace

In 1904, a committee considering the re-organisation of the College recommended that it be moved to Guindy.[7]: 247 This move finally occurred in 1923.[10]

In 2010, a roof collapsed in the Humayun Mahal and as of 2013 the Public Works Department, which was charged with the palace's maintenance, had not cleared the debris. Also in 2010, following an inspection, the building was declared not fit for occupation as it was structurally unstable. Commenting on this in 2013 an engineer said "We realised that it was beyond restoration."[2] In 2012, a fire, which killed a member of the fire service,[11] gutted the Khalsa Mahal.[6] K. V. Ramalingam, Public Works Department minister, said that as only the walls remained the building would have to be demolished. A descendant of the Nawab Wallajah, Nawab Muhammed Abdul Ali, called on Chief Minister Jayalalithaa to restore Chepauk Palace.[11] Until the southern building, Khalsa Mahal, was gutted by fire, it had remained virtually as it was first built. It had at the west and south minareted entrances and was a handsome two-story building.[6]

In 2013, there was a further roof collapse in the Humayun Mahal.[2] In 2017, Kalas Mahal was restored and will be the home of the National Green Tribunal, Southern Bench. Also in 2017 the PWD started the process of restoring Humayun Mahal.[12]

Architecture

The Chepauk Palace comprises two blocks—the northern block is known as Kalas Mahal while the southern block is known as Humayun Mahal.[1] The palace is built over an area of 117 acres and is surrounded by a wall.[1] The Humayun Mahal is spread over 66,000 square feet and has ventilators on the terrace and a connecting corridor to the Kalas Mahal.[13]

In 2017, the Public Works Department submitted a proposal to the tourism department to restore Humayun Mahal at a cost of ₹ 380 million.[13]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Srinivasachari, C. S. (1939). History of the city of Madras written for the Tercentenary Celebration Committee. Madras: P. Varadachary & Co. p. 181.

- 1 2 3 4 Ramkumar, Pratiksha (21 September 2013). "Once crown of Chennai, Chepauk Palace now falling to pieces". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- 1 2 Srinivasachari, C. S. (1939). History of the city of Madras written for the Tercentenary Celebration Committee. Madras: P. Varadachary & Co. p. 243.

- ↑ Lakshmi, K. (22 August 2017). "Chepauk Palace, an iconic structure". The Hindu. Chennai: The Hindu. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ Muthiah, S. (2004). Madras Rediscovered. East West Books (Madras) Pvt Ltd. pp. 166–168. ISBN 81-88661-24-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Muthiah, S (17 February 2013). "The Mahals of Chepauk". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 University of Madras (1957). History of Higher Education in South India, Vol. II, University of Madras 1857-1957 Affiliated Institutions (PDF). Madras: University of Madras. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2017.

- ↑ "College of Engineering, Guindy, History". Anna University. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ↑ "Madras Series I: Chepauk Palace". TuckDB.org. 1911. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ Peer Mohamed, K.R. (1996). History of Progress of Education in Madras City (1854-1947). Chennai: University of Madras. p. Ch V, p 182. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017.

- 1 2 Kumar, G Pramod (18 January 2012). "Chennai outraged: 224-year-old Chepauk palace gutted in fire". FIRSTPOST. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ↑ Lakshmi, K. (22 August 2017). "Chepauk Palace, an iconic structure". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- 1 2 K., Lakshmi (13 December 2017). "3 historic buildings to rise from the ruins". The Hindu. Chennai: Kasturi & Sons. p. 2. Retrieved 17 December 2017.