36°58′N 76°22′W / 36.967°N 76.367°W

Hampton Roads | |

|---|---|

| Virginia Beach–Norfolk–Newport News, VA–NC, Metropolitan Statistical Area | |

Satellite view of Hampton Roads with the Hampton Roads channel at center. (City urban centers visible, clockwise from top: Newport News, Hampton, Norfolk, Portsmouth) | |

Flag | |

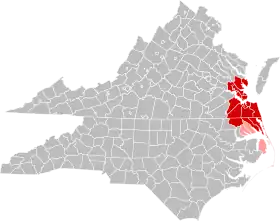

Jurisdictions in the Hampton Roads MSA are colored in red. Jurisdictions in the CSA, but not the MSA, are colored in pink. | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Virginia North Carolina |

| Independent cities | - Virginia Beach - Norfolk - Chesapeake - Newport News - Hampton - Portsmouth - Suffolk - Williamsburg - Franklin - Poquoson |

| Counties | - James City County - York County - Isle of Wight County - Southampton County - Gloucester County - Mathews County - Camden (N.C.) County - Currituck (N.C.) County - Gates (N.C.) County |

| Settled | 1607 |

| Area | |

| • Metropolitan area | 3,729.76 sq mi (9,660.0 km2) |

| • Land | 2,889.16 sq mi (7,482.9 km2) |

| • Water | 840.6 sq mi (2,177 km2) |

| • Urban | 527 sq mi (1,360 km2) |

| Elevation | 0–144 ft (0–34 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Metropolitan area | 1,799,674 |

| • Density | 463.50/sq mi (178.96/km2) |

| • CSA | 1,890,162 |

| GDP | |

| • MSA | $116.686 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | EST |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT |

| Zip Codes | VA:230xx,231xx,233xx,234xx, 235xx,236xx,237xx,238xx NC: 279xx |

| Area codes | 757, 804, 948, 252 |

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James, Nansemond, and Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's Point where the Chesapeake Bay flows into the Atlantic Ocean, and the surrounding metropolitan region located in the southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina portions of the Tidewater Region.

Comprising the Virginia Beach–Norfolk–Newport News, VA–NC, metropolitan area and an extended combined statistical area that includes the Elizabeth City, North Carolina, micropolitan statistical area and Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, micropolitan statistical area, Hampton Roads is known for its large military presence, ice-free harbor, shipyards, coal piers, and miles of waterfront property and beaches, all of which contribute to the diversity and stability of the region's economy.

The body of water known as Hampton Roads is one of the world's largest natural harbors (more accurately a roadstead or "roads"). It incorporates the mouths of the Elizabeth, Nansemond, and James rivers, together with several smaller rivers, and empties into the Chesapeake Bay near its mouth leading to the Atlantic Ocean.[2][3]

The land area includes a collection of cities, counties, and towns on the Virginia Peninsula and in South Hampton Roads. Some of the outlying areas further from the harbor may or may not be included as part of "Hampton Roads", depending upon the organization or usage. For example, as defined for federal economic purposes, the Hampton Roads metropolitan statistical area (MSA) includes two counties in northeastern North Carolina and two counties in Virginia's Middle Peninsula. The Virginia Beach–Norfolk–Newport News, VA–NC, MSA has an estimated 2022 population of 1,806,840, making it the 37th-largest metropolitan area in the United States.[4] The Combined Statistical Area includes three additional counties in North Carolina, pushing the regional population to 1,898,944 residents, the 32nd-largest CSA in the country.[5]

The area is home to hundreds of historical sites and attractions. The harbor was the key to Hampton Roads' growth, both on land and in water-related activities and events. While the harbor and its tributaries were (and still are) important transportation conduits, at the same time they presented obstacles to land-based commerce and travel.

Creating and maintaining adequate infrastructure has long been a major challenge. The Hampton Roads Bridge–Tunnel (HRBT) and the Monitor–Merrimac Memorial Bridge–Tunnel (MMMBT) are major harbor crossings of the Hampton Roads Beltway interstate, which links the large population centers of Hampton Roads. In 2009, the Hampton Roads Transportation Authority (HRTA) was abolished by the Virginia General Assembly less than two years after its creation.[6] In 2014, the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission was established to oversee the Hampton Roads Transportation Fund.

Etymology

The term "Hampton Roads" is a centuries-old designation that originated when the region was a struggling English outpost nearly four hundred years ago.

The word "Hampton" honors one of the founders of the Virginia Company of London and a great supporter of the colonization of Virginia, Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton. The early administrative center of the new colony was known as Elizabeth Cittie, named for Princess Elizabeth, the daughter of King James I, and formally designated by the Virginia Company in 1619. The town at the center of Elizabeth Cittie became known as "Hampton", and a nearby waterway was designated Hampton Creek (also known as Hampton River).

Other references to the Earl include the area to the north across the bay (in what is now the Eastern Shore) which became known as Northampton, and an area south of the James River which became Southampton. As with Hampton, both of these names remain in use today.

The term "Roads" (short for roadstead) indicates the safety of a port; as applied to a body of water, it is "a partly sheltered area of water near a shore in which vessels may ride at anchor".[7] Examples of other roadsteads are Castle Roads, in another of the Virginia Company's settlements, Bermuda, and Lahaina Roads, in Hawaii.

In 1755, the Virginia General Assembly recorded the name "Hampton Roads" as the channel linking the James, Elizabeth, and Nansemond rivers with the Chesapeake Bay.[8]

Hampton Roads is among the world's largest natural harbors. It is the northernmost major East Coast port of the United States which is ice-free year round. (This status is claimed with the notable exception of the extraordinarily cold winter of 1917, which was the entire U.S.'s coldest year on record.)

Over time, the entire region has come to be known as "Hampton Roads", a label more specific than its other moniker, "Tidewater Virginia", which includes the whole coastal region of the state. The U.S. Postal Service changed the area's postmark from "Tidewater Virginia" to "Hampton Roads, Virginia" beginning in 1983.[8]

Definitions

Counties and independent cities

The U.S. Census Bureau defines the "Virginia Beach–Norfolk–Newport News, VA–NC, MSA" as 19 county-level jurisdictions—six counties and ten independent cities in Virginia, and three counties in North Carolina. While the borders of what locals call "Hampton Roads" may not perfectly align with the definition of the MSA, Hampton Roads is most often the name used for the metropolitan area.

"Virginia Beach–Norfolk–Newport News, VA–NC, MSA" is a U.S. Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). In 2022, the population was estimated to be 1,806,840.[9]

Since a state constitutional change in 1871, all cities in Virginia are independent cities and they are not legally located in a county. The OMB considers these independent cities to be county-equivalents for the purpose of defining MSAs in Virginia. Each MSA is listed by its counties, then cities, in alphabetical order and not by size.

In Virginia

The MSA consists of these locations in Virginia:[10]

Counties

| # | Independent city | County | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2019 (estimate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Virginia Beach | – | – | 8,091 | 172,106 | 262,199 | 393,069 | 425,257 | 437,994 | 449,974 |

| 2 | Norfolk | - | 213,513 | 305,872 | 307,951 | 266,979 | 261,229 | 234,403 | 242,803 | 242,742 |

| 3 | Chesapeake | – | – | – | 89,580 | 114,486 | 151,976 | 199,184 | 222,209 | 244,835 |

| 4 | Newport News | – | – | – | – | – | 170,045 | 180,150 | 180,719 | 179,225 |

| 5 | Hampton | - | – | – | – | – | 133,811 | 146,437 | 137,436 | 134,510 |

| 6 | Portsmouth | – | 80,039 | 114,773 | 110,963 | 104,577 | 103,910 | 100,565 | 95,535 | 94,398 |

| 7 | Suffolk | – | – | – | – | 47,621 | 52,141 | 63,677 | 84,585 | 92,108 |

| 8 | Williamsburg | – | – | – | – | – | 11,530 | 11,998 | 14,068 | 14,954 |

| 9 | Poquoson | – | – | – | – | – | 11,005 | 11,566 | 12,150 | 12,271 |

| 10 | Franklin | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 7,967 |

| – | South Norfolk (defunct, 1950–1963) | – | 10,434 | 22,035 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 11 | – | James City County, VA | – | – | – | – | 34,859 | 48,102 | 67,009 | 76,523 |

| 12 | – | York County, VA | – | – | – | – | 42,422 | 56,297 | 65,464 | 68,280 |

| 13 | – | Gloucester County, VA | – | – | – | – | 30,131 | 34,780 | 36,858 | 37,348 |

| 14 | – | Isle of Wight County, VA | – | – | – | – | 25,503 | 29,728 | 35,270 | 37,109 |

| 15 | – | Currituck County, NC | – | – | – | 11,089 | 13,736 | 18,190 | 23,547 | 27,763 |

| 16 | – | Gates County, NC | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12,197 | 11,562 |

| 17 | – | Mathews County, VA | – | – | – | – | 8,348 | 9,207 | 8,978 | 8,834 |

| 18 | – | Southampton County, VA | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 17,631 |

| 19 | – | Camden County, NC | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10,867 |

| – | – | Surry County, VA | – | – | – | – | – | 6,829 | – | – |

| – | – | Norfolk County, VA (defunct, 1950–1963) | 99,537 | 51,612 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| – | – | Princess Anne County, VA (defunct, 1950–1963) | 42,277 | 77,127 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Metropolitan Area total | 445,800 | 579,510 | 680,600 | 806,951 | 1,443,715 | 1,576,370 | 1,676,822 | 1,768,901 |

| Virginia Peninsula Metropolitan Population History 1960–1980[11] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Independent City | County | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | |||||

| 1 | Newport News | – | 113,662 | 138,177 | 144,903 | |||||

| 2 | Hampton | - | 89,258 | 120,779 | 122,617 | |||||

| 3 | Williamsburg | – | – | – | 9,870 | |||||

| 4 | Poquoson | – | – | – | 8,726 | |||||

| 5 | – | York County, VA | 21,583 | 33,203 | 35,463 | |||||

| 6 | – | James City County, VA | – | – | 22,763 | |||||

| 7 | – | Gloucester County, VA | – | – | 20,107 | |||||

| Metropolitan Area total | 224,503 | 292,159 | 364,449 | |||||||

In North Carolina

The MSA also includes the following locations in North Carolina:

Evolution of Hampton Roads

The Hampton Roads metropolitan area was first defined in 1950 as the "Norfolk–Portsmouth Metropolitan Statistical Area". It comprised the independent cities of Norfolk, Portsmouth and South Norfolk and the counties of Norfolk and Princess Anne. In 1952, Virginia Beach separated from Princess Anne County.[12]

In 1963, Virginia Beach and Princess Anne County merged, retaining the name Virginia Beach. The city was added to the MSA that year, while South Norfolk lost its metropolitan status. Also in 1963, Norfolk County and the City of South Norfolk merged to create the city of Chesapeake.[13]

In 1970, Chesapeake was added to the MSA,[14] while Virginia Beach became a primary city.[15]

In 1973, Currituck County, North Carolina was added to the MSA.[16]

In 1983, the "Newport News–Hampton Metropolitan Statistical Area", comprising the cities of Newport News, Hampton, Poquoson and Williamsburg, and the counties of Gloucester, James City and York, was combined with the Norfolk–Virginia Beach–Portsmouth MSA and renamed the "Norfolk–Virginia Beach–Newport News MSA".

In 1993, Isle of Wight, Mathews and Surry counties were added. Although Virginia Beach had passed Norfolk as the state's largest city by 1990, it was not made the first primary city of the MSA until 2010.

As a result of the 2010 Census, Gates County, North Carolina was added to the MSA, while Surry County, Virginia was removed.[17]

Combined Statistical Area

The Virginia Beach–Norfolk, VA–NC, Combined Statistical Area additionally includes the Elizabeth City, NC, Micropolitan Statistical Area, comprising:

and the Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, Micropolitan Statistical Area, comprising:

The estimated population in 2022 of the Combined Statistical Area was 1,898,944. It is the 32nd largest in the country. Among the metropolitan areas in Virginia, only the Northern Virginia portion of the Washington–Arlington–Alexandria, DC–VA–MD–WV, MSA is larger.

Geography

The metropolitan area and water area is in the Tidewater region, a low-lying plains region composed of southeastern portions of Virginia and northeastern portions of North Carolina.

The water area known as Hampton Roads is a wide channel through which the waters of the James River, Nansemond River, and Elizabeth River pass (between Old Point Comfort to the north and Sewell's Point to the south) into the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean.[18]

Norfolk and Hampton Roads are among the worst-hit parts of the United States by the effects of global warming. As of 2016, the region is a few decades ahead in feeling the effects of sea-level rise compared to many American coastal areas.[19][20][21][22]

The geology and topography of the Hampton Roads region is influenced by the Chesapeake Bay impact crater, one of three factors contributing to the sinking of Hampton Roads at a rate between 15 and 23 centimeters (5.9 and 9.1 inches) per century.[23]

The region has extensive natural areas, including 26 miles (42 km) of Atlantic Ocean and Chesapeake Bay beaches, the Great Dismal Swamp, picturesque rivers, state parks, wildlife refuges, and botanical gardens. Inland from the bay, the region includes Lake Drummond, one of only two natural lakes in Virginia, and miles of waterfront property along the various rivers and waterways. The region's native flora is consistent with that of the Southeast Coastal Plain and the lower Southeast Maritime Forest.

The land area that constitutes Hampton Roads varies depending upon perspective and purpose. Most of Hampton Roads' land is geographically divided into 2 smaller regions: the eastern portion of the Virginia Peninsula (the Peninsula) and South Hampton Roads (locally known as "the Southside"), which are separated by the harbor. When speaking of communities of Hampton Roads, virtually all sources include the seven major cities, two smaller ones, and three counties within those two subregions.

In addition, the Middle Peninsula counties of Gloucester and Mathews, while not part of the geographical Hampton Roads area, are included in the metropolitan region's population, as is a small portion of northeastern North Carolina (Currituck County). Due to a peculiarity in the drawing of the Virginia-North Carolina border, Knott's Island in that county is connected to Virginia by land, but is only accessible to other parts of North Carolina by water via a ferry system.

Each of the following current cities, counties and towns is included by at least one of the three organizations that define Hampton Roads:

The Hampton Roads area consists of nine independent cities (which are not part of any county). Chesapeake, Norfolk, Portsmouth, Suffolk, and Virginia Beach cover the Southside of Hampton Roads while Hampton, Newport News, Poquoson, and Williamsburg are on the Peninsula. Franklin borders Suffolk but the Census Bureau does not consider it part of the metro area.[24]

The metro area has one county in North Carolina, Currituck. The remaining counties, in Virginia, include Isle of Wight and Surry on the Southside, James City and York on the Virginia Peninsula, and Gloucester and Mathews on the Middle Peninsula. While Southampton is adjacent to Surry, Isle of Wight, and the City of Suffolk, the Census Bureau does not consider it part of the metro area.[24]

Five incorporated towns are in the metro area, including Claremont in Surry County, Dendron in Surry County, Smithfield in Isle of Wight County, Surry, Surry County's seat, and Windsor in Isle of Wight County. (Two other incorporated towns, Boykins and Courtland, are in Southampton County, and therefore, like the county within which they are located, are not part of the federally defined metropolitan area).[24]

Other unincorporated towns and communities in the metropolitan area that are not within its cities include Gloucester Courthouse and Gloucester Point in Gloucester County, Isle of Wight Courthouse, Rushmere, Rescue, Carrollton, Benns Church, and Walters in Isle of Wight County, Yorktown, Grafton, Seaford, and Tabb in York County, Jamestown, Ford's Colony, Grove, Lightfoot, Toano, and Norge in James City County, Moyock, Knotts Island, and Currituck in Currituck County, North Carolina.[24]

The Hampton Roads MSA, with a population of about 1.7 million, is the seventh-largest metropolitan area in the Southeastern United States, after the Washington metropolitan area; Miami–Fort Lauderdale–Pompano Beach, FL, MSA; Atlanta–Sandy Springs–Marietta, GA, MSA, Tampa–St. Petersburg–Clearwater, FL, MSA; Orlando–Kissimmee, FL, MSA; and Charlotte–Gastonia-Rock Hill, NC–SC, MSA.

History

17th–19th centuries

The first colonists arrived in 1607 when English Captain Christopher Newport landed at Cape Henry, today's City of Virginia Beach, an event now called the "First Landing." However, his party moved on, in search of a more defensible area upriver, mindful of competitors such as the Spanish, who had built a failed settlement on the Virginia Peninsula known as the Ajacán Mission.

After exploring the James River, they established the first successful English colony in the New World on Jamestown Island on May 14, 1607.[25] But the low, marshy site proved unhealthy and most of the colonists died, before a new Governor, Lord De La Warr (Delaware) arrived with John Rolfe, who would establish the Virginia tobacco industry.[25]

The harbor and rivers of Hampton Roads were immediately recognized as prime locations for commerce, shipbuilding and military installations, with the fortifications at Old Point Comfort established as early as 1610, and Gosport Navy Yard (later Norfolk Naval Shipyard) in 1767. The decisive battle of the Revolution was won at Yorktown in 1781, and the first naval action of the War of 1812 took place in Hampton Roads, when a Royal Naval vessel was seized by the American privateer Dash. Later the entrance from Chesapeake Bay was equipped with new fortifications (Fort Monroe and Fort Wool), much of the building work being supervised by a young military engineer Robert E. Lee.

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), the historic Battle of Hampton Roads between the first American ironclad warships, the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia, took place off Sewell's Point in 1862. The battle was inconclusive, but Union forces later took control of Hampton Roads, Norfolk, and the lower James River, though they were thwarted from venturing further upstream by a strong Confederate battery at Drewry's Bluff. Also in 1862, Fort Monroe was the launching place for Union General George McClellan's massive advance up the Virginia Peninsula, which almost reached the Confederate capital Richmond, before the Seven Days Battles forced him back. In 1865, as the Confederacy was near collapse, President Abraham Lincoln met with three senior Confederates at Hampton Roads in an unsuccessful bid for a negotiated peace.[26]

Some former slaves had been camped near Fort Monroe, where they were declared to be Contraband of war, instead of being returned to their former owners. Booker T. Washington was among the freedmen who attended the local school, which evolved into the present-day Hampton University.

20th century

The Jamestown Exposition for the 300th anniversary of the 1607 founding of Jamestown was held at Sewell's Point in a rural section of Norfolk County in 1907.

President Theodore Roosevelt arrived by water in the harbor of Hampton Roads, as did other notable persons such as Mark Twain and Henry Huttleston Rogers, who both arrived aboard the latter's steam yacht Kanawha. A major naval display was featured, and the U.S. Great White Fleet made an appearance. The leaders of the U.S. Navy apparently did not fail to note the ideal harbor conditions, as was later proved.

Beginning in 1917, as the United States became involved in World War I under President Woodrow Wilson, formerly rural Sewell's Point became the site of what grew to become the largest Naval Base in the world which was established by the United States Navy and is now known as the Naval Station Norfolk.

Twice in the 20th century, inhabitants mostly African American were displaced when land along the northern side of the Peninsula primarily in York County west of Yorktown was taken in large tracts for military use during World War I and World War II, creating the present-day U.S. Naval Weapons Station Yorktown, which includes Cheatham Annex, and a former Seabee base which became Camp Peary.

Communities including "the Reservation", Halstead's Point, Penniman, Bigler's Mill, and Magruder were all lost and absorbed into the large military bases.

Although some left the area entirely, many of the displaced families chose to relocate nearby to Grove, an unincorporated town in southeastern James City County where many generations of some of those families now reside. From a population estimated at only 37 in 1895, Grove had grown to an estimated 1,100 families by the end of the 20th century. (To its north, Grove actually borders the Naval Weapons Station property and on its extreme east, a portion of the U.S. Army's land at Fort Eustis extends across Skiffe's Creek, although there is no direct access to either base).

Colonial Williamsburg

It was the dream of an Episcopal priest to save his 18th-century church building by turning Williamsburg into the world's largest living museum. Williamsburg replaced Jamestown at the very end of the 17th century after a disastrous fire. It was the capital of the colony and the new State of Virginia from 1699 to 1780. The capital was moved to Richmond in 1780. Williamsburg became a "sleepy" small town. During the Civil War the Battle of Williamsburg was fought nearby during the Peninsula Campaign in the spring months of 1862. The decaying town was not located along any major waterway and did not have railroad access until 1881. Perhaps due to the secure inland location originally known as Middle Plantation Williamsburg missed growth and economic expansion in the 19th century. The main economic engines were The College of William & Mary and Eastern State Hospital. The College of William and Mary was chartered by the Crown and is the only pre-Independence college to have kept it. In addition to the city's historic past, quite a few buildings of antiquity from the 18th century were still extant, although time was taking a toll by the early 20th century. The Reverend Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin of Bruton Parish Church motive was to only to save historic church building which was secured by 1907. He subsequently served in Rochester, New York for many years. Upon returning to Williamsburg in 1923 he realized that many of the other colonial-era buildings were deteriorating and their existence was at risk.

Goodwin dreamt of a much larger restoration of the colonial town. A cleric of modest means, he first sought support and financing from a number of sources before successfully drawing the interests before receiving major financial support from Standard Oil heir and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. and his wife Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. The result is the creation of Colonial Williamsburg with extensive restoration of buildings such as the Wren Building of the College of William & Mary and the Governor's Palace, and the transformation of downtown Williamsburg area into Historic District of restored buildings. Many 19th century buildings were removed.

By the 1930s, Colonial Williamsburg had become the centerpiece of the Historic Triangle of Colonial Virginia. These were, of course, Jamestown, where the colony started, Williamsburg, and Yorktown, where independence from Great Britain was won. The three points were joined by the U.S. National Park Service's Colonial Parkway, a remarkable accomplishment in course of 27 years. The Historic Triangle area of the Hampton Roads region became one of the largest tourist attractions in Virginia. In Dr. Goodwin's words: "Williamsburg is Jamestown continued, and Yorktown is Williamsburg vindicated."

Government

The area consists of ten independent cities and six counties. Each independent city has the powers and responsibilities of a county, including maintaining roads, courts, schools, and public safety. Some cities share these responsibilities with an adjoining county. Incorporated towns located within counties in Virginia operate with some level of autonomy, with some larger Towns exercising more autonomy than others.

The localities come together to consult on regional issues. Virginia defines regional planning districts by law. District members are usually independent cities and counties. Localities around the state may belong to more than one Planning District, as their constituents may have interests which cross over individual planning district boundaries.

The Hampton Roads Planning District Commission (HRPDC) currently includes 16 cities and counties and one incorporated town in Virginia, representing over 1.7 million people.

The 17 jurisdictions include:

- the Cities of Chesapeake, Franklin, Hampton, Newport News, Norfolk, Poquoson, Portsmouth, Suffolk, Virginia Beach, and Williamsburg,

- the Counties of Gloucester, Isle of Wight, James City, Southampton, Surry, and York

- the Town of Smithfield

There are incorporated towns in three of the counties (Isle of Wight, Southampton and Surry) within the district.[27]

The differences between the service area of the HRPDC and the federally defined metropolitan statistical area (MSA) are:

- Southampton County and the City of Franklin are not in the MSA.

- Mathews County is in the MSA but not the HRPDC.

- The MSA includes Currituck County and Gates County, North Carolina, but the HRPDC does not.

The Federal government has two major research laboratories in the area. NASA-Langley, on the northeast edge of Hampton near Poquoson, is the home of a variety of aeronautics research, including several one-of-a-kind wind tunnels. The Department of Energy's Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (known as 'Jefferson Lab')[28] conducts cutting edge physics research in Newport News; the lab hosts the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF)[29] and a kilowatt-class free-electron laser.[30]

U.S. military

The military has a large presence in the region. Area military facilities (alphabetically) include:

- Camp Allen, in Norfolk

- Camp Peary, in York County

- Coast Guard 5th District, in Portsmouth

- Coast Guard Base Portsmouth in Portsmouth

- Coast Guard Training Center Yorktown, in York County

- Fleet Training Center Dam Neck, in Virginia Beach

- Fort Eustis, in Newport News

- Fort Monroe, in Hampton (closed in September 2011)

- Joint Expeditionary Base East, in Virginia Beach

- Lafayette River Complex (LRC), in Norfolk

- Langley Air Force Base, in Hampton

- Naval Air Station Oceana, in Virginia Beach

- Naval Amphibious Base Little Creek, in Virginia Beach

- Naval Auxiliary Landing Field Fentress, in Chesapeake

- Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, in Portsmouth

- Naval Station Norfolk, in Norfolk

- Naval Support Activity Hampton Roads, in Chesapeake

- Naval Consolidated Brig, Chesapeake

- Naval Support Activity Northwest Annex, in Chesapeake

- Naval Weapons Station Yorktown, in York County

- Norfolk Naval Shipyard, in Portsmouth (not to be confused with Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, in Kittery, Maine)

- Saint Julian's Creek Naval Depot Annex, in Chesapeake

Economy

Hampton Roads is home to two Fortune 500 companies. Representing the retail and shipbuilding industry, these two companies are located in Chesapeake and Newport News.

|

Hampton Roads has become known as the "world's greatest natural harbor." The port is located only 18 miles (29 km) from open ocean on one of the world's deepest, natural ice-free harbors. Since 1989, Hampton Roads has been the mid-Atlantic leader in U.S. waterborne foreign commerce and is ranked second nationally behind the Port of South Louisiana based on export tonnage. When import and export tonnage are combined, the Port of Hampton Roads ranks as the third largest port in the country (following the ports of New Orleans/South Louisiana and Houston). In 1996, Hampton Roads was ranked ninth among major U.S. ports in vessel port calls with approximately 2,700. In addition, this port is the U.S. leader in coal exports. The coal loading facilities in the Port of Hampton Roads are able to load in excess of 65 million tons annually, giving the port the largest, most efficient and modern coal loading facilities in the world.

It is little surprise therefore that the Hampton Roads region's economic base is largely port-related, including shipbuilding, ship repair, naval installations, cargo transfer and storage, and manufacturing related to the processing of imports and exports. Associated with the ports' military role are almost 50,000 federal civilian employees.

The harbor of Hampton Roads is an important highway of commerce, especially for the cities of Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Newport News.[18]

Huntington Ingalls Industries (formerly Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company), was created in 2008 as a spinoff of Northrop Grumman Newport News and is the world's largest shipyard. It is located a short distance up the James River. In Portsmouth, a few miles up the Elizabeth River, the historic Norfolk Naval Shipyard is located. BAE Systems, formerly known as NORSHIPCO, operates from sites in the City of Norfolk. There are also several smaller shipyards, numerous docks and terminals.

Massive coal piers and loading facilities were established in the late 19th and early 20th century by the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O), Norfolk and Western Railway (N&W), and Virginian Railway (VGN). The latter two were predecessors of the Norfolk Southern Railway, a Class I railroad which has its headquarters in Norfolk, and continues to export coal from a large facility at Lambert's Point on the Elizabeth River. CSX Transportation now serves the former C&O facility at Newport News. (The VGN's former coal facility at Sewell's Point has been gone since the 1960s, and the property is now part of the expansive Norfolk Navy Base).

Federal impact

Almost 80% of the region's economy is derived from federal sources. This includes the large military presence, but also NASA and facilities of the Departments of Energy, Transportation, Commerce and Veterans Affairs. The region also receives a substantial impact in government student loans and grants, university research grants, and federal aid to cities.

The Hampton Roads area has the largest concentration of military bases and facilities of any metropolitan area in the world. Nearly one-fourth of the nation's active-duty military personnel are stationed in Hampton Roads, and 45% of the region's $81B gross regional output is Defense-related.[32][33] All five military services' operating forces are there, as well as several major command headquarters: Hampton Roads is a chief rendezvous of the United States Navy, and the area is home to the Allied Command Transformation, which is the only major military command of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on U.S. soil. Langley Air Force Base is home to Air Combat Command (ACC). The Norfolk Navy Base is located at Sewell's Point near the mouth, on the site used for the tercentennial Jamestown Exposition in 1907. For a width of 500 feet (150 m) the Federal government during 1902 through 1905 increased its minimum depth at low water from 25.5 to 30 feet (8 to 9 m),[18] and the channel has now been dredged to a depth of 55 feet (17 m) in some places.

NASA's Langley Research Center, located on the Peninsula adjacent to Langley Air Force Base in Hampton, is home to scientific and aerospace technology research. The Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (commonly known as Jefferson Lab) is located nearby in Newport News.

Commercial growth

The area's experiences with commercial and retail centers began early in 1918. Afton Square, located in the Cradock naval community of Portsmouth, was the first planned shopping center in the US and has served as template for future developments throughout the nation.[34]

Hampton Roads experienced tremendous growth during and after World War II. In the 1950s, a trend in retail was the shopping center, a group of stores along a common sidewalk adjacent to off-street parking, usually in a suburban location.

In 1959, one of the largest shopping centers on the east coast of the US was opened at the northeast corner of Military Highway and Virginia Beach Boulevard on property which had formally been used as an airfield. The new JANAF Shopping Center, located in Norfolk, featured acres of free parking and dozens of stores. Backed by retired military personnel, the name JANAF was an acronym for Joint Army Navy Air Force.[35]

During the 1950s and early 1960s, other shopping centers in Hampton Roads were developed, such as Wards Corner Shopping Center, Downtown Plaza Shopping Center and Southern Shopping Center in Norfolk; Mid-City Shopping Center in Portsmouth; Hilltop Shopping Center (now known as The Shops at Hilltop) in Virginia Beach; Riverdale Shopping Center in Hampton and the Warwick-Denbigh Shopping Center in Newport News.

In the late-1960s, a new type of shopping center came to Hampton Roads: the Indoor Shopping Mall. In 1965, South Hampton Roads broke ground on its first shopping mall in Virginia Beach, known as Pembroke Mall. The mall opened in 1966, and became Hampton Road's newest indoor shopping destination. The Virginia Peninsula had its first indoor shopping mall in 1973, with Coliseum Mall. Coliseum Mall drew so much traffic from Interstate 64, that a towering flyover was built at the Mercury Boulevard and Coliseum Drive intersection, to accommodate eastbound mall traffic, from the Mercury Boulevard interchange. Coliseum Mall was demolished to make way for the open air mixed-use development Peninsula Town Center. Also in the 1970s, Tower Mall was built in Portsmouth, but was torn down and turned into the Victory Crossing shopping development. In Norfolk, Military Circle Mall on Military Highway was built across Virginia Beach Boulevard from the large JANAF Shopping Center with its own high-rise hotel right in the center. In 1981, Greenbrier Mall gave Chesapeake a shopping mall of its own as well, and Virginia Beach got the massive Lynnhaven Mall the same year.

Chesapeake Square Mall was constructed in Chesapeake, Virginia in 1989, near the border of Suffolk, Virginia, and has spawned a number of shopping centers in the surrounding areas.

MacArthur Center opened in March 1999, which made downtown Norfolk a prime shoppers destination, with the region's first Nordstrom department store anchor. MacArthur Center is compared to other downtown malls, such as Baltimore's Harborplace, Indianapolis' Circle Centre Mall, Atlanta's Lenox Square Mall and most comparably to The Fashion Centre at Pentagon City near Washington, D.C., in Arlington, Virginia.

Currently, Virginia Beach's Lynnhaven Mall is the region's largest shopping center with nearly 180 stores, and is one of the region's biggest tourist draws, with the Virginia Beach Oceanfront, Colonial Williamsburg, Busch Gardens Williamsburg and MacArthur Center.

For a long time, the indoor shopping malls were seen as largely competitive with small shopping centers and traditional downtown type areas. However, in the 1990s and since, the "big-box stores" on the Peninsula and Southside, such as Wal-mart, Home Depot, and Target have been creating a new competitive atmosphere for the shopping malls of Hampton Roads.

Several older malls such as Pembroke and Military Circle have since their grand openings been renovated, and others have been closed and torn down. Newmarket North Mall is now NetCenter, a business center. Coliseum Mall, in Hampton, has been redeveloped as Peninsula Town Center in a new style, in step with the latest commercial real estate trend: the nationwide establishment of "lifestyle centers". Additional malls which have closed include Mercury Mall in Hampton (converted to Mercury Plaza Shopping Center in the mid-1980s, then completely torn down in 2001), and Tower Mall in Portsmouth (Built in the early 1970s, then torn down in 2001).

| Shopping mall | Location | Number of stores | Area | Year opened |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lynnhaven Mall | Virginia Beach | 180 | 1,400,000 sq ft (130,000 m2) | 1981 |

| MacArthur Center | Norfolk | 140 | 1,100,000 sq ft (100,000 m2) | 1999 |

| Chesapeake Square Mall | Chesapeake | 130 | 800,000 sq ft (70,000 m2) | 1989 |

| Greenbrier Mall | Chesapeake | 120 | 809,017 sq ft (75,160 m2) | 1981 |

| Patrick Henry Mall | Newport News | 120+ | 714,310 sq ft (66,400 m2) | 1987 |

| The Gallery at Military Circle | Norfolk | 120 | 944,447 sq ft (87,742 m2) | 1970 |

| Pembroke Mall | Virginia Beach | 100 | 650,000 sq ft (60,000 m2) | 1966 |

America's first region

In late 2006, the Hampton Roads Partnership, a non-profit organization representing 17 localities (ten cities, six counties, and one town), all local universities and major military commands as well as leading businesses in southeastern Virginia, commenced a campaign aimed at branding the land area of Hampton Roads as "America's First Region".

The new title is based on events in 1607 when English Captain Christopher Newport's three ships – the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery landed at Cape Henry along the Atlantic Coast in what is today Virginia Beach. After 18 days of exploring the area, the ships and their crews arrived at Jamestown Island where they established the first English speaking settlement to survive in the New World on May 14, 1607.

Because the region's east–west boundaries (now the City of Virginia Beach and James City County) have not changed since 1607, the Partnership felt justified in labeling Hampton Roads "America's First Region". It unveiled the new brand before 800 people at the annual meeting of the Hampton Roads Chamber of Commerce on December 13, 2006. A video shown that afternoon included endorsements from mayors and county board of supervisors chairs representing Hampton, Norfolk, Virginia Beach, Williamsburg and James City County as well as the Governor of Virginia, Timothy Kaine.[36]

The mission of Hampton Roads Economic Development Alliance (HREDA) is a non-profit organization dedicated to business attraction—marketing the Hampton Roads region as the preferred location for business investment and expansion. HREDA represents the cities of Chesapeake, Hampton, Newport News, Norfolk, Poquoson, Portsmouth, Suffolk, Virginia Beach, Williamsburg and Franklin, as well as the counties of Gloucester, James City, Isle of Wight, York, and Southampton.[37]

Transportation

Historically, from the earliest times, the harbor was the key to the Hampton Roads area's growth, both on land and in water-related activities and events. The harbor and its tributary waterways were (and still are) both important transportation conduits and obstacles to other land-based commerce and travel. Yet, the community leaders learned to overcome them.

In modern times, the region has faced increasing transportation challenges as it has become largely urbanized, with additional traffic needs. In the 21st century, the conflicts between traffic on vital waterways and land-based travel continue to present the area's leaders with extraordinary transportation challenges, both for additional capacity, and as the existing infrastructure, much of it originally built with toll revenues, has aged without an adequate source of funding to repair or build replacements. The now-closed Kings Highway Bridge in Suffolk and the Jordan Bridge closed by neighboring Chesapeake in 2008 were each built in the 1920s. These were considered locally prime examples of this situation.[38][39]

In 2007, the new Hampton Roads Transportation Authority (HRTA) was formed under a controversial state law to levy various additional taxes to generate funding for major regional transportation projects, including a long-sought and costly additional crossing of the harbor of Hampton Roads (The Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel, Monitor-Merrimac Bridge Tunnel, and the James River Bridge are the existing crossings). As of March 2008, although its projects were considered to be needed, the agency's future was in some question while its controversial sources of funding were being reconsidered in light of a Virginia Supreme Court decision.[40]

Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport, located in Newport News, and Norfolk International Airport, in Norfolk, both cater to passengers from Hampton Roads. The primary airport for the Virginia Peninsula is the Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport. The Airport experienced a 4th year of record, double-digit growth through 2011, making it one of the fastest growing airports in the country.[41] In 2012 however, the airport lost its biggest carrier and has seen massive declines in passenger service, culminating in layoffs of police officers and many other staff. Norfolk International Airport (IATA: ORF, ICAO: KORF, FAA LID: ORF), serves the region. The airport is located near Chesapeake Bay, along the city limits of Norfolk and Virginia Beach.[42] Seven airlines provide nonstop services to twenty five destinations. ORF had 3,703,664 passengers take off or land at its facility and 68,778,934 pounds of cargo were processed through its facilities.[43]

The Hampton Roads Executive Airport (KPVG), located on US460/US58, is the state's 3rd busiest General Aviation airport and hosts the largest number of general aviation aircraft of any Virginia airport. The airport offers flight training, avionics services, as well as major and minor airframe and powerplant repairs. There is also a sit-down restaurant in the terminal.

The Chesapeake Regional Airport (KCPK) provides similar general aviation services and is located in the city of Chesapeake. Additionally, many local general aviation pilots fly from the nearby Suffolk (KSFQ), Wakefield (KAKQ) and Franklin (KFKN) airports.

Amtrak serves the region with Northeast Regional trains to its Norfolk, Williamsburg and Newport News stations. The lines run west to Richmond then north to Washington, D.C., and major cities north to Boston. Connecting buses are available between the Norfolk and Newport News stations and from both stations to Virginia Beach. A high-speed rail connection at Richmond to both the Northeast Corridor and the Southeast High Speed Rail Corridor are also under study.[44][45]

Intercity bus service is provided by Greyhound Lines (Carolina Trailways) with bus stations in Newport News, Hampton, and Norfolk.[46] Transportation within Hampton Roads is served by a regional bus service, Hampton Roads Transit.[47] Local routes serving Williamsburg, James City County, and upper York County is operated by Williamsburg Area Transit Authority.[48]

A light rail service known as The Tide was constructed in Norfolk. It began service in August 2011.[49] Operated by Hampton Roads Transit, it is the first light rail service in the state. It is projected to have a daily ridership of between 7,130 and 11,400 passengers a day.[50] There has also been a light rail study in the Hampton – Newport News areas.[51] In the 2016 election, a referendum was on the ballot in Virginia Beach to kill the planned, and mainly state-funded extension of the Tide to the commercial center of Virginia Beach and ultimately to the oceanfront. The ballot initiative won, cancelling the project. The transit authority and the state were left with new light rail cars and major infrastructure for the extension to be disposed of. There are no further plans for light rail mass transit initiatives within Virginia Beach.

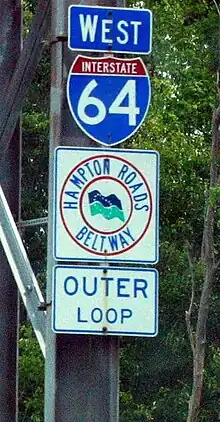

The Hampton Roads area has an extensive network of Interstate Highways, including the Interstate 64, the major east–west route to and from the area, and its spurs and bypasses of I-264, I-464, I-564, and I-664.

The Hampton Roads Beltway extends 56 miles (90 km) on a long loop through the region, crossing the harbor on two toll-free bridge–tunnel facilities. These crossings are the Hampton Roads Bridge–Tunnel between Phoebus in Hampton and Willoughby Spit in Norfolk and the Monitor–Merrimac Memorial Bridge–Tunnel between Newport News and Suffolk. The Beltway connects with another Interstate highway and three arterial U.S. Highways at Bower's Hill near the northeastern edge of the Great Dismal Swamp. Other major east–west routes are U.S. Route 58, U.S. Route 60, and U.S. Route 460. The major north–south routes are U.S. Route 13 and U.S. Route 17.

There are also two other tunnels in the area, the Midtown Tunnel, and the Downtown Tunnel joining Portsmouth and Norfolk, as well as the 17-mile (27 km)-long Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, a toll facility which links the region with Virginia's Eastern Shore which carries US 13.[52] The original Downtown Tunnel in conjunction with the Berkley Bridge were considered a single bridge and tunnel complex when completed in 1952, perhaps stimulating the innovative bridge-tunnel design using man-made islands when the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel was planned, first opening in 1957. The George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge is a major toll bridge connecting U.S. Highway 17 on the Peninsula at Yorktown with Virginia's Middle Peninsula region. Another major crossing of waterways is the James River Bridge, carrying US 17 US 258, and SR 32 from Newport News to Isle of Wight County.[53]

The region is notable in that it has 2 types of public transport services via ferries. A passenger ferry is operated on the Elizabeth River between downtown areas of Norfolk and Portsmouth by HRT.[54] The Jamestown Ferry (also known as the Jamestown-Scotland Ferry) is an automobile ferry system on the James River connecting Jamestown in James City County with Scotland in Surry County. It carries State Route 31. Operated by VDOT, it is the only 24-hour state-run ferry operation in Virginia and has over 90 employees. It operates four ferryboats, the Pocahontas, the Williamsburg, the Surry, and the Virginia. The facility is toll-free.[55]

Demographics

According to the 2010 Census, the overall racial composition of Hampton Roads was as follows:[56]

- White or Caucasian: 59.6%

- Black or African American: 31.3%

- American Indian: 0.4%

- Asian: 3.5%

- Some other race: 1.7%

- Two or more races: 3.4%

In addition, 5.4% of the population were Hispanic or Latino (of any race). 57.2% of the population were of non-Hispanic White background.

Religious

A small minority of Virginians in the Hampton Roads region believe in pantheism.[57]

Immigration status

In 2014-2018, there were 106,682 immigrants in the region, making up 7% of the population.[58]

Ethnic groups

In 2010 around 40,000 people of Filipino origin lived in that region.[59]

Chinese immigration to Norfolk occurred after 1885, and in 1995 300 families were members of that city's Chinese Community Association.[60]

Culture

The area is most often associated with the larger American South. People who have grown up in the Hampton Roads area have a unique Tidewater accent which sounds different from a stereotypical Southern accent. Vowels have a longer pronunciation than in a regular southern accent.[61]

Flag

In 1998, a flag representing the Hampton Roads region was adopted. The design of the flag was created by a contest. The winner, sixteen-year-old Andrew J. Wall of Frank W. Cox High School in Virginia Beach, raised the new regional flag for the first time on the mast of a ship moored in the harbor.

As conceived by student Andrew Wall and embellished by the selection committee, his flag is highly symbolic:

- The ring of sixteen white stars stands for the cities and counties that comprise the region of Hampton Roads. The blue upper panel refers to the sea and sky, recalling the first European settlers at Jamestown in 1607, the first battle between ironclad ships in 1862, the importance of shipbuilding and ship repair in the area, as well as maritime commerce, fishing, recreational boating, and the major military and government installations around the area's shores. Agriculture, the environment, tourism, industry, and a healthy quality of life are suggested by the lower panel of green. The wavy white central band with three crests suggests past, present, and future. The wave also recalls the surf and sand dunes of the area as seen from the sea. Water is the central theme. It touches all the components and binds them together.[62]

Sites of interest

Parks and recreation

The Norfolk Botanical Garden, opened in 1939, is a 155-acre (0.6 km2) botanical garden and arboretum located near the Norfolk International Airport. It is open year-round.[63]

The Virginia Zoological Park, opened in 1900, is a 65-acre (26 ha) zoo with hundreds of animals on display, including the critically endangered Siberian tiger and threatened white rhino.[64]

First Landing State Park and False Cape State Park are both located in coastal areas in Virginia Beach. Both offer camping facilities, cabins, and outdoor recreation activities in addition to nature and history tours. First Landing is the site of Cape Henry while False Cape is located at the southeastern end of Virginia Beach.[65][66]

Newport News Park is located in the northern part of the city of Newport News. The city's golf course also lies within the park along with camping and outdoor activities. There are over 30 miles (48 km) of trails in the Newport News Park complex. The park has a 5.3-mile (8.5-km) multi-use bike path. The park offers bicycle and helmet rental, and requires helmet use by children under 14. Newport News Park also offers an archery range, disc golf course, and an "aeromodel flying field" for remote-controlled aircraft, complete with a 400 ft (120 m) runway.[67]

The region also has amusement parks which attract tourists and locals alike. The Virginia Beach Oceanfront has Atlantic Fun Park (formerly called "Virginia Beach Amusement Park"). Virginia Beach also has Ocean Breeze Waterpark, Shipwreck Golf, and Motor World which were formerly combined into one as "Ocean Breeze Fun Park". As separate parks, they provide miniature golf, go-karts, water slides, pools, climbing wall, paintball area, and kiddie rides.[68][69] Busch Gardens Williamsburg and Water Country USA are the major theme parks in Williamsburg.

Historic Triangle

The Historic Triangle is located on the Virginia Peninsula and includes the colonial communities of Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Yorktown. The sites are linked by a scenic roadway, the National Park Service's Colonial Parkway.

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent English settlement in the Americas. It was established by the Virginia Company of London as "James Fort" on May 4, 1607, and was considered permanent after brief abandonment in 1610. It followed several failed attempts, including the Lost Colony of Roanoke. Jamestown served as the capital of the colony of Virginia for 83 years, from 1616 until 1699.

Historic Jamestowne is the archaeological site on Jamestown Island and is a cooperative effort by Jamestown National Historic Site (part of Colonial National Historical Park) and Preservation Virginia. Jamestown Settlement, a living history interpretive site, is operated by the Jamestown Yorktown Foundation, a state agency of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Williamsburg was founded in 1632 as Middle Plantation, a fortified settlement on high ground between the James and York rivers. The city served as the capital of the Colony of Virginia from 1699 to 1780 and was the center of political events in Virginia leading to the American Revolution. The College of William & Mary, established in 1693, is the second-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and the only one of the nine colonial colleges located in the South; its alumni include three U.S. presidents as well as many other important figures in the nation's early history.

The city's tourism-based economy is driven by Colonial Williamsburg, the restored Historic Area of the city. Modern Williamsburg is also a college town, inhabited in large part by William & Mary students and staff.

Yorktown is one of the eight original shires formed in colonial Virginia in 1682. The town is most famous as the site of the siege and subsequent surrender of General Charles Cornwallis to General George Washington and the French Fleet during the American Revolutionary War on October 19, 1781. Although the war would last for another year, this British defeat at Yorktown effectively ended the war. Yorktown also figured prominently in the American Civil War (1861–1865), serving as a major port to supply both northern and southern towns, depending upon who held Yorktown at the time. It is the eastern terminus of the Colonial Parkway connecting these locations. Yorktown is also the eastern terminus of the TransAmerica Trail, a bicycle touring route created by the Adventure Cycling Association.

Peninsula museums

The Mariners' Museum, founded in 1930 by Archer and Anna Huntington, is an institution dedicated to bringing maritime history to the world. It is currently home to the USS Monitor Center where 210 tons of artifacts recovered from the USS Monitor are held, including the gun turret. The museum also consists of a 550-acre park and the Mariners' Lake, through which is the five-mile Noland Trail. The permanent collection at the museum totals about 32,000 objects, equally divided between works of art and three-dimensional objects. The Mariners' Museum Library and Archive, now located in the Trible Library at Christopher Newport University, consists of over 78,000 books, 800,000 photographs, films and negatives, and over one million archival pieces, making it the largest maritime library in the Western Hemisphere.[70]

The Virginia War Museum covers American military history. The museum's collection includes, weapons, vehicles, artifacts, uniforms and posters from various periods of American history. Highlights of the museum's collection include a section of the Berlin Wall and the outer wall from Dachau Concentration Camp.[71]

The Virginia Living Museum, first established in 1966, combines the elements of a native wildlife park, science museum, aquarium, botanical preserve, and planetarium. The exhibits are themed on the geographic regions of Virginia, from the Appalachian Mountains to the offshore waters of the Atlantic Ocean, and includes more than 245 different animal species.[72]

The Peninsula Fine Arts Center in Newport News contains a rotating gallery of art exhibits. The center also contains a Studio Art School of private and group instruction for all ages. It maintains a permanent "Hands on For Kids" gallery designed for children and families to interact in what the center describes as "a fun, educational environment that encourages participation with art materials and concepts."[73]

The Hampton University museum was established in 1868 in the heart of the historic Hampton University campus. The museum is the oldest African American museum in the United States and one of the oldest museums in the State of Virginia. It contains over 9,000 objects, including African American fine arts, traditional African, Native American, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Island, and Asian art.[74]

The Charles H. Taylor Arts Center is Hampton's public access arts center. It offers a series of changing visual art exhibitions as well as a quarterly schedule of classes, workshops and educational programs.[75]

The Downing-Gross Cultural Arts Center in SE Newport News contains a community-based art gallery, as well as arts classrooms and the Ella Fitzgerald Theater.[76]

The Casemate Museum (where former Confederate President Jefferson Davis was imprisoned) is at Fort Monroe in the historic Phoebus area at Old Point Comfort in Hampton.[77]

NASA Langley Research Center is in Hampton, the original training ground for the Mercury Seven, Gemini, and Apollo Astronauts. Visitors are able to learn about the region's aviation history at the Virginia Air and Space Center in Hampton.[78]

Air Power Park is an outdoor on-site display of various aircraft and a space capsule. It is located on Mercury Boulevard at the intersection of LaSalle Blvd, near the AF Base.

The Biblical Art Gallery at Ivy Farms Baptist Church is Virginia's largest collection of pre-1900s religious art.

South Hampton Roads

The Chrysler Museum of Art, located in the Ghent district of Norfolk, is the region's foremost art museum and is considered by The New York Times to be the finest in the state.[79] Of particular note is the extensive glass collection and American neoclassical marble sculptures.

Nauticus, the National Maritime Center, opened on the downtown waterfront in 1994. It features hands-on exhibits, interactive theaters, aquaria, digital high-definition films and an extensive variety of educational programs. Since 2000, Nauticus has been home to the battleship USS Wisconsin, one of the last battleships to be built in the United States. It served briefly in World War II and later in the Korean and Gulf Wars.[80] The General Douglas MacArthur Memorial, located in the 19th-century Norfolk court house and city hall in downtown, contains the tombs of the late General and his wife, a museum and a vast research library, personal belongings (including his famous corncob pipe) and a short film that chronicles the life of the famous General of the Army.[81]

Also in downtown Norfolk and inside Nauticus is the Hampton Roads Naval Museum, an official U.S. Navy museum that focuses on the 220 plus year history of the Navy within the region.

The Children's Museum of Virginia in Portsmouth has one of the largest collection of model electric trains and other toys.

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth is one of the oldest shipyards and has the first dry dock on display.

Rivers Casino Portsmouth, in Portsmouth, boasts a 50,000-square-foot (4,600 m2) casino floor with slots, table games, poker tables, and a sportsbook.

The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge (in Suffolk and Chesapeake) is accessed from U.S. Route 17 in Chesapeake.

The Suffolk-Nansemond Museum is in the restored Seaboard and Virginian Railway passenger train station in Suffolk.

The Isle of Wight Museum is in Smithfield.

The Contemporary Art Center of Virginia located in Virginia Beach features the significant art of our time.

Music and venues

The Hampton Roads region has a thriving music scene, with a heavy concentration thereof in the Virginia Beach, Chesapeake, and Norfolk areas. Many clubs, venues, and festivals exist within the region, all playing host to a wide variety of musical styles. There are a few hundred bands that play routinely in the region, spanning multiple genres. There are also twenty to thirty musical acts based in the region that perform throughout Hampton Roads and its surrounding areas on a "full-time" basis.

In addition, plenty of well known acts have come from the area. Some of the major rock/pop artists include Bruce Hornsby, Gary "U.S." Bonds, Juice Newton, Mae, Seven Mary Three, Gene Vincent, Keller Williams, and Steve Earle. Ella Fitzgerald is the most recognizable jazz musician from the area. Robert Cray and Ruth Brown are both prominent blues and R&B artists. Tommy Newsom is another famous jazz musician. Many prominent rap and hip hop artists come from the area including Chad Hugo, Clipse, Magoo, Missy Elliott, Nicole Wray, Pharrell Williams, Quan, Teddy Riley, and Timbaland.

The region has a number of venues hosting live music and performances. Several of the larger (in order of maximum seating capacity) are:

- Veterans United Home Loans Amphitheater in Virginia Beach (seating 20,000)

- Norfolk Scope Arena in Norfolk (seating 13,800)

- Hampton Coliseum in Hampton (seating 13,800)

- Kaplan Arena in Williamsburg (seating 10,175)

- Ted Constant Convocation Center at Old Dominion University in Norfolk (seating 9,500)

- Portsmouth Pavilion in Portsmouth (seating 7,500)

- Le Palais Royal Theatre at Busch Gardens Williamsburg in James City County (seating 5,600)

- Ferguson Center for the Arts in Newport News (seating 1,725 and 453 in 2 separate concert halls)

- Lake Matoaka Amphitheatre at The College of William & Mary in Williamsburg (seating 1,700)

- The NorVa in Norfolk (standing 1,500)

Dozens of much smaller commercial establishments offer live music and other entertainment such as comedy shows and mystery dinner-theater throughout the region.

Other notable Hampton Roads "firsts"

America's first free public schools, the Syms and Eaton free schools (later combined as Syms-Eaton Academy), were established in Hampton in 1634 and 1659 respectively. The Syms-Eaton Academy was later renamed Hampton Academy and in 1852 became part of the public school system, thus Hampton High School lays claim to being the oldest public school in the United States.[82] The trust fund created from the Syms and Eaton donations has remained intact since the 17th century and was incorporated into support for the Hampton public school system.[83]

In 1957, the Hampton Roads Bridge–Tunnel was the first bridge–tunnel complex in the world, to be followed by the area's much longer Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel in 1963. This was followed by the Monitor–Merrimac Memorial Bridge–Tunnel in 1992.

Education

Hampton Roads' individual cities and counties administer their own K-12 education for their localities. In addition to public education, area residents have many private and religious school options.

The area also has a number of higher education options for area residents. Some offer only associates and technical degrees and certificates, while others award advanced degrees, including doctorates. Some are publicly funded, but the region also has a number of private and for-profit colleges. Additionally, a number of universities have established satellite campuses in the region.

Higher education

Public universities:

The College of William & Mary in Williamsburg was founded in 1693 and has served as the second oldest institution of higher education in the United States.[84] Old Dominion University, founded as the Norfolk Division of the College of William and Mary in 1930, became an independent institution in 1962 and now offers degrees in 68 undergraduate and 95 (60 masters/35 doctoral) graduate degree programs. Norfolk's Eastern Virginia Medical School, founded as a community medical school by the surrounding jurisdictions in 1973, is noted for its research into reproductive medicine[85] and is located in the region's major medical complex in the Ghent district. Norfolk State University is the largest majority black university in Virginia and offers degrees in a wide variety of liberal arts.[86] Christopher Newport University serves as a public university and is located in Newport News.[87]

Private universities:

Regent University, a private university founded by Christian evangelist, television host and leader Pat Robertson, has historically focused on graduate education but is attempting to establish an undergraduate program as well.[88] Atlantic University, associated with the Edgar Cayce organization's Association for Research and Enlightenment (ARE), offers instruction in New Age subjects and an M.A. in Transpersonal Studies.[89] Virginia Wesleyan University is a small private liberal arts college on the border of Norfolk and Virginia Beach.[90] Hampton University, a private HBCU university, has a long history serving Hampton.[91]

Universities with satellite campuses:

Several universities based outside Hampton Roads offer a limited selection of classes in the area. Virginia Tech and University of Virginia have established a joint teaching center in Newport News. George Washington University and Averett University also maintain campuses there. Troy University, Florida International University, and Saint Leo University offer classes, primarily connected to one or more of the area's military bases.

University consortia:

The National Institute of Aerospace (NIA) is a consortium of member universities: Georgia Tech, Hampton University, North Carolina A&T, North Carolina State, Old Dominion University, University of Virginia, Virginia Tech, the College of William and Mary, and Christopher Newport University. Their unique approach allows students pursuing M.S. and PhD degrees the opportunity to take classes from any member university taught at the institute.

Technical education:

Area residents also have options for training for technical professions. The Apprentice School was founded in 1919 and offers four/five-year programs in mechanical and technical fields associated with the shipbuilding industry. Graduates from the Apprentice School go on to work at the Newport News Shipbuilding.[92] Technology-focused ECPI University has campuses in Virginia Beach and Newport News[93] while ITT Technical Institute has a campus in Norfolk. Bryant & Stratton College has campuses in Virginia Beach Town Center and Peninsula Town Center.[94] The Culinary Institute of Virginia[95] is located in Norfolk. The Art Institute of Virginia Beach offers programs in the media arts, design and culinary arts fields.

Two-year colleges:

Three institutions in the Virginia Community College System offer affordable higher education options for area residents. Tidewater Community College in Norfolk, Virginia Beach, Chesapeake, and Portsmouth, Paul D. Camp Community College in Suffolk, Franklin, and Smithfield, and Virginia Peninsula Community College in Hampton and Williamsburg offer two-year degrees and specialized training programs.[96][97]

Religious education

Bible training schools include Hampton University and Regent University, but also Canaan Theological College & Seminary, Bethel College and Victory Baptist Bible College and Seminary in Hampton, Tabernacle Baptist Bible College & Theological Seminary, Central Baptist Theological Seminary in Virginia Beach, Providence Bible College & Theological Seminary in Norfolk and the Hampton Roads campus of the John Leland Center for Theological Studies.

Media

Newspapers

Three daily newspapers serve Hampton Roads: The Virginian-Pilot in the Southside, the Daily Press on the Peninsula, and the six days a week Suffolk News-Herald that serves Suffolk and Franklin.[98] Smaller publications include the Williamsburg-James City County area's twice-weekly Virginia Gazette (the state's oldest newspaper[99]), the New Journal and Guide, and Inside Business, the area's only business newspaper.

Newspapers serving the Hampton Roads area include:

- Daily Press – Newport News

- The Virginian-Pilot – Norfolk

- Suffolk News-Herald – Suffolk

- The Flat Hat – student newspaper of the College of William & Mary

- Inside Business – Norfolk (business news)

- The New Journal and Guide – Norfolk

- Tidewater News – Franklin

- The Virginia Gazette – Williamsburg

Magazines

Coastal Virginia Magazine is one of the region's city and lifestyle magazine. The publication is published eight times a year and covers all of Hampton Roads and the Eastern Shore of Virginia.[100] Coastal Virginia Magazine was formerly known as Hampton Roads Magazine.

Hampton Roads Times serves as an online magazine for the region.

Suffolk Living Magazine is another of the region's city and lifestyle magazines. The publication is published four times a year and covers the City of Suffolk. Suffolk Publications also produces Virginia-Carolina Boomers, a regional guide for Boomers in the area, which comes out twice a year.[101]

Television

The Hampton Roads designated market area (DMA) is the 42nd largest in the U.S. with 712,790 homes (0.64% of the total U.S.).[102] The major network television affiliates are WTKR-TV 3 (CBS), WAVY 10 (NBC), WVEC-TV 13 (ABC), WGNT 27 (CW), WTVZ 33 (MyNetworkTV), WVBT 43 (Fox), and WPXV 49 (Ion Television). WHRO-TV 15 serves as the region's primary member station of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS); WUND 2 – an Edenton, North Carolina-based satellite of PBS North Carolina, a state network of PBS member stations owned by the University of North Carolina – serves as a secondary PBS outlet for the area. Area residents also can receive independent stations, such as WSKY broadcasting on channel 4 from the Outer Banks of North Carolina, WGBS-LD broadcasting on channel 11 from Hampton, and WTPC 21, a TBN affiliate out of Virginia Beach.

Cable television service in most Hampton Roads localities is provided by Cox Communications. Suffolk, Franklin, Isle of Wight, and Southampton are served by Charter Communications.[103] Verizon Fios service is currently available in parts of the region and continues to expand, offering a non-satellite alternative to Cox. DirecTV and Dish Network are also popular as an alternative to cable television.

Radio

Norfolk is served by a variety of radio stations on the FM and AM dials, with towers located around the Hampton Roads area. These cater to many different interests, including news, talk radio, and sports, as well as an eclectic mix of musical interests.[104]

Sports

The Virginia Beach-Norfolk, VA-NC Combined Statistical Area is one of the largest statistical areas in the United States without a professional sports franchise in one of the five major North American sports leagues (NFL, MLB, NBA, NHL, MLS).

Team sports

Norfolk serves as home to two professional franchises, the Norfolk Tides of the International League and the Norfolk Admirals of the ECHL.[105] The Tides play at Harbor Park, seating 12,067 and opened in 1993. The Admirals play at the Norfolk Scope arena, seating 8,725 or 13,800 festival seating, which opened in 1971. Hampton Roads was formerly home to the ABA Virginia Squires, alternating between Norfolk and Hampton, as well as Richmond and Roanoke. The Squires folded in 1976, after the league merged with the NBA.

Lionsbridge FC competes in USL League Two, the top pre-professional men's soccer league in North America. The club began play in 2018 and was named USL League Two Franchise of the Year in 2019. They play home games on the campus of Christopher Newport University. The Peninsula Pilots play in the Coastal Plain League, a summer baseball league. The Pilots play in Hampton at War Memorial Stadium seating 5,125 and opened in 1948.[106]

On the collegiate level, four Division I programs—two on the Southside and two on the Peninsula—field teams in many sports, including football, basketball, and baseball; three currently play football in the second-tier FCS, while ODU recently moved up to the FBS football. The Southside boasts the Old Dominion Monarchs and the Norfolk State Spartans, both in Norfolk, while the Peninsula features the William & Mary Tribe in Williamsburg and Hampton Pirates in Hampton. W&M is a member of the Colonial Athletic Association. Norfolk State and Hampton, both historically black institutions, compete in the Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference and CAA respectively.[107][108][109][110] ODU joined Conference USA, an FBS football conference, as a full FBS member in 2015. The area also has two Division III programs, one in each subregion—the Virginia Wesleyan Marlins on the border of Virginia Beach and Norfolk,[111] and the Christopher Newport University Captains in Newport News. The Captains sponsor fourteen sports and currently compete in the USA South Athletic Conference,[112] but will move to the Capital Athletic Conference in July 2013.

Virginia Beach served as home to one soccer team, the Hampton Roads Piranhas, a women's team in the W-League from 1995 to 2013.[113] The Piranhas played at the Virginia Beach Sportsplex. The Virginia Beach Sportsplex, seating 11,541 and opened in 1999, contains the central training site for the U.S. women's national field hockey team.[114] The Sportsplex was expanded to accommodate the Virginia Destroyers, a franchise in the United Football League which relocated from Orlando. The Destroyers played in Virginia Beach from 2011 to 2012, and won the 2011 league championship. The North American Sand Soccer Championships, a beach soccer tournament, is held annually on the beach in Virginia Beach.

The Norfolk Nighthawks were a charter member of the Arena Football League's minor league, af2. They ceased operations in 2003 after their fourth season. Also, the Virginia Beach Mariners of soccer's USL First Division were active from 1994 until 2006.

Hampton Roads is 130 miles (210 km) from the nearest major sports teams in Washington, D.C., and Raleigh, North Carolina. Another significant issue with the area as a sports market is internal transportation. The metropolitan area is split into two distinct parts by its eponymous harbor; as of 2012, the harbor has only three widely separated road crossings (the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel, and James River Bridge), each with two lanes of traffic in each direction. In addition, the area has two other major tunnels, plus several drawbridges on key highway corridors.

Hampton Roads previously hosted a successful franchise in the American Basketball Association, although it was never a full-time home for that team. Its highest-ranking teams as of 2015 are the Norfolk Admirals of the ECHL, the Norfolk Tides of the IL, and Lionsbridge FC of USL League Two. Virginia is also the most populous state without a major league team playing within its borders, though its northern reaches are served by the Washington clubs — two of which, the NHL's Capitals and NFL's Washington Commanders, have their operational headquarters and practice facilities in Virginia. Washington Commanders owner Daniel Snyder, through a separate company, owns two radio stations, WXTG and WXTG-FM, in the Norfolk market. The Hampton Roads television market is ranked 42nd in the U.S.

There have been several failed projects to attract major league teams to Hampton Roads:

- In 1997, Norfolk presented a proposal to bring an expansion hockey team to Hampton Roads, but that initiative failed. The team was going to be called the Hampton Roads Rhinos.

- In 2002, Norfolk presented a proposal to bring the Charlotte Hornets basketball team to southeastern Virginia, but New Orleans won the bid for the team, renaming it the New Orleans Hornets.

- In 2004, Norfolk presented a proposal to bring the Montreal Expos baseball team to the metro area, but Washington, D.C. won the bid for the team, renaming it the Washington Nationals.

- In 2012, there were talks of the Sacramento Kings of the NBA moving to a proposed new arena in Virginia Beach near the Oceanfront.[115]

Individual sports

The Hampton Coliseum, seating 10,761 to 13,800 festival seating, hosts the annual Virginia Duals wrestling events, and the annual Hampton Jazz Festival. The arena opened in 1970 and has previously hosted Hampton University basketball along with NBA and NHL preseason exhibition games.

Virginia Beach is home to the East Coast Surfing Championships, an annual contest of more than 100 of the world's top professional surfers and an estimated 400 amateur surfers. This is North America's oldest surfing contest, and features combined cash prizes of $40,000.[116]

Langley Speedway in Hampton, seating 6,500, hosts stock car races every weekend during spring, summer, and early fall.[117]

The Kingsmill Championship, an event on the LPGA Tour, is contested annually on Mother's Day weekend at Kingsmill Resort near Williamsburg.

In 1998, 2001, 2006, 2010, and 2015 the Hampton Roads Sports Commission hosted the AAU Junior Olympics.[118]

Professional wrestling

Hampton Roads has hosted many professional wrestling events throughout the years. The Norfolk Scope has served as the site of these events, including Total Nonstop Action Wrestling's Destination X, World Championship Wrestling's Starrcade (1988), World War 3 1995 and 1996, and WWF/WWE's The Great American Bash (2004) and the 2011 Slammy Awards.[119] Norfolk Scope was also the site of an infamous episode of WCW Monday Nitro, where several members of the World Wrestling Federation stable D-Generation X literally drove a tank to the entryway of the Scope, thus "invading" the competition. The Hampton Coliseum has also hosted many events, including RAW, in April 1998, August 2005, May 2007, January 2008, and July 2011, as well as SmackDown! and for ECW on Sci Fi in December 2006. In January 2008, WWE broadcast its first television show taped in high definition from Hampton, Virginia.

The Hampton Roads area is also home to at least one professional wrestling promotion, Vanguard Championship Wrestling, which holds events throughout the region, and has a weekly television show on the local Fox affiliate.

See also

References

- ↑ "Total Gross Domestic Product for Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC (MSA)". fred.stlouisfed.org.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map, accessed April 1, 2011

- ↑ "Norfolk Development – Norfolk Development". Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ↑ Bureau, US Census. "2020 Population and Housing State Data". Census.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ↑ "Combined Metropolitan Areas (Tibet) (USA): Combined, Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas - Population Statistics, Charts and Map". citypopulation.de. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ↑ "LIS > Bill Tracking > HB1580 > 2009 session". lis.virginia.gov.

- ↑ "the definition of road". Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- 1 2 "What's in a name? – Hampton Roads". Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2017.