| Second Battle of St. Michaels | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

George Cockburn Thomas Sydney Beckwith | Perry Benson | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Royal Navy * 1st Bn Royal Marines * 2nd Bn Royal Marines British Army * 102nd Regiment of Foot |

12th Maryland Brigade * 4th Maryland Regiment * 26th Maryland Regiment * 9th Cavalry District | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Land: 2,100 | Land: 500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | 14 captured | ||||||

The Second Battle of St. Michaels was a raid conducted on Maryland's Eastern Shore by British soldiers during the War of 1812. The raid occurred on August 26, 1813, at points between Tilghman Island and the town of St. Michaels, Maryland. Local militia defended against the raiders.

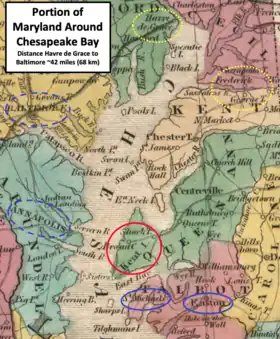

The Maryland Eastern Shore communities had access to the Chesapeake Bay, which was the main shipping route to important American cities such as Baltimore and Washington, D.C. St. Michaels was one of the communities with access to the bay, and was a target for the British because of its shipbuilding. About two weeks earlier, the town was successfully defended by artillerists from the local militia when British forces attacked on August 10 in the Battle of St. Michaels.

A large British force landed on the shore at Auld's Point early in the morning on August 26. After marching to the main road, the force split into a small group of 300 and a large group of about 1,800. The small group moved toward Tilghman Island in pursuit of a militia company. Two merchant vessels were burned and a small number of militiamen were captured. Most of the militia fled to safety. The larger group of British moved toward St. Michaels. They were confronted by Maryland militia numbering less than one third of the size of the British force. After a short exchange of artillery and musket fire, the British mysteriously withdrew.

Background

On June 17, 1812, the United States Senate approved a resolution passed by the United States House of Representatives that declared war against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (a.k.a. Great Britain). President James Madison signed the resolution into law on June 18.[1][2] The country was not united in its feelings toward Great Britain. Many members of the Federalist political party, a coalition of bankers and businessmen, were opposed to the war.[3][4] Contrary to the Federalists, members of the Democratic-Republican Party, who had a numerical superiority, believed a war was justified.[5]

After the declaration of war, the British government declared the ports of the United States to be in a state of blockade.[6] They began stricter enforcement of the blockade in 1813, when ships were sent to close the port of New York and others further south, including those on the Chesapeake Bay. Early in February 1813, British ships under the command of Rear Admiral George Cockburn took possession of Hampton Roads at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, which stopped traffic in and out of the bay. This effectively closed major ports such Norfolk in Virginia and the Port of Baltimore in Maryland.[6]

Beginning in spring, Cockburn conducted raids on towns along the Chesapeake. The raids involved the destruction or removal of property including crops and livestock.[7] On May 3, Cockburn burned most of Havre de Grace, Maryland.[8][Note 1] More Maryland coastal towns, Georgetown and Fredericktown, were burned on May 6.[11] First Lady Dolley Madison called Cockburn's raids "savage", and Cockburn threatened to capture and parade her through London.[7][Note 2] Cockburn established a policy that if a town kept no guns or militia, he would leave them unharmed.[13]

Opposing forces

Great Britain

Vice Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren was appointed commander of North America and the West Indies during the summer of 1812, and in January 1813 Cockburn reported to Warren in HMS Marlborough.[14] Cockburn led the August 26 raid that began on Auld's Point (Wades Point) near St. Michaels. He had eight ships, plus the First and Second battalions of Royal Marines. He also had the 102nd Regiment of Foot, which was an army regiment.[15] He used about 2,100 men who came ashore in 60 barges.[Note 3] Cockburn led 300 Royal Marines while Colonel Thomas Sydney Beckwith led a larger group of 1,800 men.[17]

United States

Talbot County, which contains the towns Easton, St. Michaels, and other smaller communities, was defended mostly by state militia in 1813. Maryland's militia was organized into three divisions with a total of 12 brigades and 11 cavalry districts.[18] Much of the Talbot County militia was formed in 1807 after the attack on the American USS Chesapeake by the British HMS Leopard.[19] Brigadier General Perry Benson, who was a veteran of the American Revolutionary War, commanded the 12th Maryland Brigade, which consisted of militia from Talbot, Caroline, and Dorchester counties.[20] His force at the battle consisted of the 4th and 26th Maryland infantry regiments, plus several companies of cavalry from the 9th Cavalry District. This force totaled to about 500 men.[17] The 4th Maryland Regiment consisted of men mostly from Easton, and had an artillery company.[21] The 26th Maryland Regiment had companies from the St. Michaels area including Bayside.[22] The 9th Cavalry District included companies from Easton, St. Michaels, and Trappe.[22]

Prelude

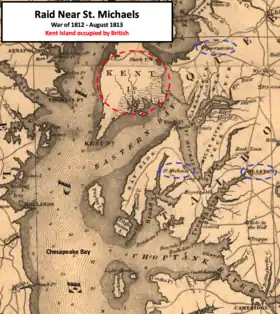

The British captured Maryland's Kent Island during early August 1813. The island is located north of St. Michaels and across the bay from the Maryland state capital, Annapolis. The British landed about 3,000 men on the island, but faced no resistance because most of the inhabitants fled when they learned of the invasion.[23][Note 4] The island had food and fresh water, and provided a base for operations against Maryland's Eastern Shore, Annapolis, Baltimore, and Washington.[25] The town of Easton, the largest city on Maryland's Eastern Shore, was also a potential target.[26]

During this time, the British had ships in Eastern Bay between Kent Island and St. Michaels, causing alarm in Queenstown, St. Michaels, Easton, and the surrounding area.[26] St. Michaels was a target because of its shipbuilding, and had already been attacked on August 10. At that time, artillerists from Talbot County's Maryland Militia prevented the British from destroying the town and its shipbuilding wharfs.[27][Note 5] St. Michaels is located on the St. Michaels River, which is a water route near Kent Island that could be used to get close to Easton.[Note 6] The Eastern Shore's only armory was located in Easton, as was a bank and plenty of goods for the British to plunder. As a precaution, Easton's bank sent its specie to Lancaster, Pennsylvania.[32] A second water route to Easton, Treadhaven Creek, was protected by a six-gun battery called Fort Stokes.[20][Note 7] Queenstown, which is less than 20 miles (32 km) from Easton and close to Kent island, was attacked on August 13.[34]

The British return to Talbot County

Much of the Talbot County militia was sent home after the repulse of the British attack on St. Michaels on August 10.[35] However, the August 13 attack on Queenstown, and rumors that the entire British fleet was planning to sail up the Choptank River, put the county on alert again.[35] The Choptank River could be used to attack St. Michaels via a branch of Broad Creek, and the Choptank could also be used to get close to Easton via Treadhaven Creek. Militia members were recalled from their homes and prepared for a British invasion of southern Talbot County.[36]

Brigadier General Benson waited near St. Michaels with 500 to 600 militiamen.[Note 8] At 3:00 am on August 26, the British sent 60 barges of troops to Auld's point (also known as Wade's Point) at Bayside.[38] HMS Conflict remained nearby in the bay. At the same time, HMS Highflyer and three schooners were moving toward the St. Michaels River from Eastern Bay.[38] Eleven more barges landed at Hamilton's Point northwest of St. Michaels.[38] Locals were informed by the British that more troops would land soon—and if the locals remained in their houses, their property would be safe.[36] Around dawn, Benson's videttes observed the British near Auld's point, which is about six miles (9.7 km) away from St. Michaels.[36] Rear Admiral Cockburn landed about 2,100 men with artillery.[17]

Cockburn's plan was to attack a militia camp he believed was located between St. Michaels and Tilghman Island.[39] He marched his men approximately two miles (3.2 km) to the main Tilghman Island–St. Michaels road, where they split into two forces. A force of 300 Royal Marines went with Cockburn southwest toward Tilghman Island.[17][Note 9] A second force, led by Colonel Thomas Sydney Beckwith, totaled to about 1,800 men and moved southeast toward St. Michaels.[17] Cockburn hoped to advance past the militia camp and then drive it toward Beckwith.[39] He was also looking for a party of deserters known to have taken a barge to the Bayside shore.[37]

Battle

Cockburn

The militia camp was not found by Cockburn because it did not exist. A small company of militia, led by Captain John Caulk, patrolled the Bayside and Tilghman's Island area.[37] Once Caulk's men discovered that their route to other militia forces near St. Michaels was blocked by Cockburn, they dispersed. Most of them escaped by crossing Harris Creek.[37] Those that were captured were taken from their homes. Two small vessels were burned, and a large amount of plunder was taken.[40] The boat used by some deserters from the British army had already been sunk, and the deserters and their sunken boat were not found.[37]

Beckwith

Beckwith marched his men along the Tilghman Island–St. Michaels road toward St. Michaels to a point where Porter Creek and Broad Creek are not far from each other. Here, he formed a line across the road. He was about two miles (3.2 km) from St. Michaels, and close to Benson's militia. Benson's men were positioned in a wooded area, making it difficult for any intruder to determine the size of the militia force.[37] Benson had three artillery pieces in the middle of his line, surrounded by infantry and cavalry.[38] Eventually the two sides exchanged fire, but what the U.S. National Park Service calls "the largest Eastern Shore battle" of the War of 1812 lasted for only a few artillery shots and musket volleys.[41] The British "mysteriously withdrew", and the reason for their withdrawal is still unknown.[42]

Aftermath

The British withdrew with their prisoners and plunder, and both forces were back aboard their ships by 5:00 PM after departing from Auld's (Wade's) Point.[39][Note 10] The ships on the St. Michaels River, and barges at Hamilton's Point, did not engage.[37][38] The only known casualties were 14 militiamen captured by Cockburn.[36] The prisoners were paroled on the next day.[43] On August 30, the British fleet was observed sailing down (south) the bay, so most of the militia was sent home.[44]

The British determined that attacks on Annapolis and Baltimore would be ill-advised because those American cities had received substantial reinforcements. They also wished to leave the region before the start of hurricane season.[45] By September, Cockburn had departed for Bermuda, and a small "skeleton force" was stationed at the Virginia Capes for blockade purposes.[46] Almost exactly one year after the Second Battle of St. Michaels, the British burned the United States Capitol and President's Mansion (White House) in Washington, DC.[47] While Easton and Annapolis were not attacked during the war, Baltimore fought off the British during September 1814 in the Battle of Baltimore.[48]

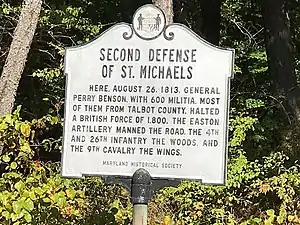

Today (2021), the Maryland Historical Trust maintains a historic marker near the spot where Benson placed his militia.[49] Little else remains from the battle, and most discussion about the War of 1812 near St. Michaels revolves around the artillery duel on August 10.[41] The St. Michaels Museum at St. Mary's Square is a small museum near the place Benson and his infantry waited during the August 10 battle.[50] A larger exhibition hall is the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, which is located on the north side of the St. Michaels harbor at Navy Point.[51]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Cockburn said his original intention at Havre de Grace was to destroy the iron works, but he burned the town because four men were killed and one wounded when he landed with a flag of truce.[9] Another source says that from Cockburn's point of view, the burning of Havre de Grace was justified because the town had an artillery battery and because the town practiced dishonorable warfare by shooting from behind trees and houses.[10]

- ↑ In mid-August 1814, Cockburn was involved in the siege and burning of Washington—a highlight of his career.[7] Dolley Madison became famous for her efforts to remove and save priceless artifacts from the White House prior to the arrival of the British troops.[12]

- ↑ A barge, or row galley, typically used oars and small sails to move men. They had a small draft in the water, and carried one long cannon.[16]

- ↑ Another source says the British occupying force on Kent Island consisted of 2,000 troops and 25 to 30 ships.[24]

- ↑ The British report that discussed the first attack on St. Michaels stated that its mission had been accomplished because it disabled a battery and did not find any ships under construction.[28] The Americans were happy with the outcome of this skirmish, since the British did not occupy the town, none of the ships in the wharfs were damaged, the town had little damage, and there was "no injury to any human being."[29]

- ↑ The St. Michaels River, also called Michaels River, is now called Miles River.[30] It is believed that the name change came from the local Quakers refusing to use the term "Saint", and therefore calling the river the "Michaels River". Over time, "Michaels" became "Miles".[31]

- ↑ Treadhaven Creek, a.k.a. Third Haven Creek, is now called Tred Avon River.[33]

- ↑ Sheads describes Benson's force as "some 500", while Tilghman produces an account that says "about six hundred".[17][37]

- ↑ As second source says the group of 300 men was from the 102nd Regiment of Foot, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Charles J. Napier.[39]

- ↑ Sheads says the British left by 9:00 AM.[17] Tilghman says the British re-embarked on their barges at 6:00 PM.[43]

Citations

- ↑ "Declaration of War with Great Britain, 1812". United States Senate. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 143–144

- ↑ "Ohio History Central - Federalist Party". Ohio History Connection. Archived from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ↑ "Federalists oppose Madison's War". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 144

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 148

- 1 2 3 "The first step was plunder without distinction". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ↑ "War of 1812 Timeline". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ↑ Marine 1913, p. 54

- ↑ Morriss 1997, p. 92

- ↑ "Kitty Knight". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ↑ "Dolley Madison". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ↑ Morriss 1997, p. 93

- ↑ Morriss 1997, p. 87

- ↑ Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 25

- ↑ Dudley 1992, pp. 374–375

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 49

- ↑ Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 17

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 146

- 1 2 Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 44

- ↑ Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 21

- 1 2 Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 22

- ↑ Marine 1913, p. 53

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 161

- ↑ Dudley 1992, p. 382

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 162

- ↑ Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 45

- ↑ Dudley 1992, p. 381

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 169

- ↑ "Miles River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 316

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 150

- ↑ "Tred Avon River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- ↑ Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 48

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 172

- 1 2 3 4 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 173

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 175

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sheads & Turner 2014, pp. 50–51

- 1 2 3 4 Whitehome 1997, p. 83

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 173–174

- 1 2 "The Town that Fooled the British?". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ↑ Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 50

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 174

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 176

- ↑ Dudley 1992, pp. 382–383

- ↑ Dudley 1992, p. 384

- ↑ "United States Senate - Burning of Washington, 1814". United States Senate. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ↑ Sheads & Turner 2014, pp. 8–9

- ↑ "Maryland's Historical Markers - Second Defense of St. Michaels". Maryland Historical Trust. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ↑ "St. Michaels Museum at St. Mary's Square". St. Michaels Museum. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum". Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

References

- Dudley, William S., ed. (1992). Naval War of 1812; A Documentary History - Volume II. Washington, District of Columbia: Naval Historical Center, Department of Navy. ISBN 978-0-16002-042-1. OCLC 12834733. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- Marine, William Matthew (1913). Dielman, Louis Henry (ed.). The British Invasion of Maryland, 1812-1815. Baltimore, Maryland: Society of the War of 1812 in Maryland. ISBN 978-0-80630-760-2. OCLC 3120839. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023.

- Morriss, Roger (1997). Cockburn and the British Navy in Transition: Admiral Sir George Cockburn, 1772-1853. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-253-0. OCLC 1166924740.

- Sheads, Scott S.; Turner, Graham (2014). The Chesapeake Campaigns 1813-15: Middle Ground of the War of 1812. Oxford, Oxfordshire, England: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-852-0. OCLC 875624797.

- Tilghman, Oswald; Harrison, Samuel A. (1915). History of Talbot county, Maryland, 1661-1861, Volume II. Baltimore, Maryland: Williams and Wilkins Company. OCLC 1541072. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- Whitehome, Joseph W.A. (1997). The Battle for Baltimore. Baltimore, Maryland: Nautical and Aviation Publishing Company of America. ISBN 978-1-87785-323-4. OCLC 1011626918.

Further reading

- Neimeyer, Charles P.; Center of Military History United States Army (2014). The Chesapeake Campaign 1813-1814 (PDF). Washington, District of Columbia: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-50564-644-3. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

External links

- The Town That Fooled the British, St Michaels MD - YouTube

- St. Michaels Harbor - YouTube (31 seconds)

- War of 1812 Chesapeake Campaign... - U.S. Army