| Prince George Circuit (1934–1966) Kyalami (1967–1985, 1992–1993) | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 33 |

| First held | 1934 |

| Last held | 1993 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Last race (1993) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

The South African Grand Prix was first run as a Grand Prix motor racing handicap race in 1934 at the Prince George Circuit at East London, Cape Province. It drew top drivers from Europe including Bernd Rosemeyer, Richard "Dick" Seaman, Richard Ormonde Shuttleworth and the 1939 winner Luigi Villoresi.

World War II brought an end to the race, but it was revived in 1960 as part of the Formula One circuit, entering the World Championship calendar two years later. It was a popular F1 event, but the Grand Prix was suspended right after the controversial 1985 race, due to the nation's policy of apartheid.[1] Following the end of apartheid in 1991, the race returned to the Formula One schedule in 1992 and 1993. The 1993 race was the last South African Grand Prix, as of 2023. Plans to revive the race in 2024 have been abandoned.[2]

History

Brown = 1934, Blue = 1936, Black = 1959

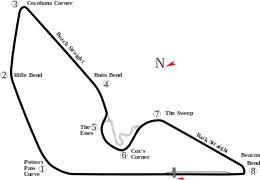

East London (1934–1966)

The first South African Grands Prix were held on a 24.4 km (15.2 mi) road course known as the Prince George Circuit, running through different populated areas of the coastal city of East London. This was shortened to 17.7 km (11.0 mi) in 1936. When racing resumed after World War II, a permanent circuit was built in 1959 that retained the name Prince George Circuit. The first World Championship F1 race in South Africa was held on 29 December 1962. In that race, Graham Hill took advantage of Jim Clark's mechanical problems with his Lotus and took race victory and the championship. The race was held at Prince George again in 1963, 1965 and 1966, the latter relegated to non-championship status as a new 3-litre formula came into effect on the same day.[3] In 1967, the race was moved to the Kyalami circuit near the high-altitude inland city of Johannesburg in the Transvaal, where it would remain as long as the South African Grand Prix was on the official Formula One calendar.

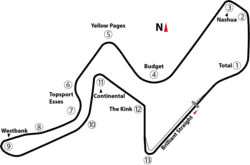

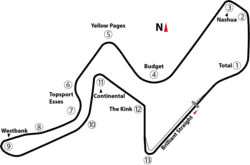

Kyalami (1967–1985,1992-1993)

The fast Kyalami circuit, which was built in the early 1960s, played host to its first South African Grand Prix in 1967, where privateer John Love nearly took victory but ran into fuel problems late in the race, and Mexican Pedro Rodríguez took victory. 1968 saw Clark take victory; he broke Juan Manuel Fangio's record for most career wins and it turned out to be his last F1 victory; he was killed at a Formula 2 race at Hockenheim later that year. 1969 saw Jackie Stewart win, and the following year 44-year-old veteran Jack Brabham won his last F1 race. 1971 saw American Mario Andretti win his maiden Grand Prix, on debut for Ferrari. 1974 saw American Peter Revson crash horribly at Barbeque Bend during testing for the race and slam head-on to the barriers; he later died from his injuries. Argentine Carlos Reutemann won for the first time at that year's event. 1975 saw South African Jody Scheckter take victory. The 1977 event was the location of one of the most gruesome crashes in history, as Tom Pryce was killed when he hit and killed track marshal Frederick Jansen Van Vuuren at full speed. Niki Lauda won the race, but the accident sent shock waves throughout the sport. 1978 saw Ronnie Peterson take a late victory from Patrick Depailler and Riccardo Patrese; the 1979 event was held in changeable weather conditions and was won by Canadian Gilles Villeneuve.

Going into the 1980s, turbo-charged cars began to dominate the Grand Prix. Because of the high altitude of the fast Kyalami circuit (approximately 6,000 feet above sea level) the forced induction turbo engines could regulate how much air went into the engine whereas the normally aspirated engines could not; the turbo-charged engines had a horsepower advantage in 1982 of 150 hp over the normally aspirated engines, and often qualified on the front row of the grid considerably faster than the normally aspirated engined cars; and the Renault team dominated both the 1980 and 1982 races; Frenchman Alain Prost won the 1982 race after he lost a wheel around mid-distance; he charged through the field and took victory from Carlos Reutemann.[4] The 1981 event was a victim of the FISA–FOCA war. As agreement could not be reached with FISA for the Grand Prix to be run as a round of the Formula One World Championship or as a non-championship Formula One race, it was officially staged as a Formula Libre event. Consequently, it was contested only by the FOCA-aligned teams, with cars which did not strictly comply with the 1981 Formula One regulations.[5] The 1983 event was the last race of that season, and it saw a three-way battle for the Drivers' Championship between Prost, Brazilian Nelson Piquet and Frenchman René Arnoux. Prost and Arnoux both went out with engine problems and Piquet took 3rd place and the Drivers' Championship; Prost made scathing comments about Renault's conservative approach to developing the car, and he was fired from the team. Piquet's Italian teammate Riccardo Patrese won the race. 1984 saw the event take place early in the season, and Prost (now driving for McLaren) started from the pit lane in the spare car after his race car didn't start. This was made legal when the first start was aborted after Briton Nigel Mansell stalled on the grid. Prost drove through the field to finish 2nd behind his teammate Niki Lauda. Briton Derek Warwick completed the podium in a Renault and Brazilian future world champion Ayrton Senna scored his first point in a Toleman, finishing 6th.

The 1985 race was mired in international controversy as nations began boycotting South African sporting events because of a state of emergency declared by the South African government in July of that year because of a surge of violence related to racial segregation in the country, called apartheid. Most people involved in Formula One were strongly against going to race in South Africa. Some governments tried to ban their drivers from going,[6] and the Ligier and Renault teams did boycott the race in line with the French Government's ban on sporting events in South Africa;[7] however French drivers Alain Prost, who had wrapped up the 1985 championship in the previous race,[8] and Philippe Streiff, both driving for British teams, did take part. British driver Nigel Mansell won his second consecutive Formula One race and his teammate Keke Rosberg stormed around the track after 2 pitstops to take 2nd, completing a 1–2 for the Williams team.[8] 1985 was the final South African Grand Prix until the end of apartheid, with FIA president Jean-Marie Balestre announcing days after the race that a Grand Prix would not return to the nation because of apartheid.[1]

After the end of apartheid in 1991, Formula One returned to Kyalami for two Grands Prix in 1992 and 1993. The 1992 event was dominated by Mansell and the 1993 running saw an intense battle between Prost, Ayrton Senna and Michael Schumacher, with Prost taking victory. In July 1993 Kyalami was sold to the South African Automobile Association, which managed to run the facility at a profit; however, running a Formula One event proved too costly and the Grand Prix did not return, that year's race having also been the last time that F1 came to the African continent.

The only South African driver to win the South African Grand Prix was Jody Scheckter in 1975. British driver Jim Clark won it 4 times and Austrian driver Niki Lauda won 3 times.

Possibility of a return

In April 2018, The South African discussed the possibility of South Africa returning to the Formula One Grand Prix calendar with Adrian Scholtz, CEO of Motorsport South Africa. He said that the main obstacles are the high costs of hosting such an event and the fact that currently no South African racetrack fulfills the FIA requirements to host a Formula One race, although Kyalami comes close.[9] In 2023, the FIA declared that the South African Grand Prix would not return to the F1 calendar for the near future due to the South African government's stance on the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[10]

Winners of the South African Grand Prix

Repeat winners (drivers)

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| Wins | Driver | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 1961, 1963, 1965, 1968 | |

| 3 | 1976, 1977, 1984 | |

| 2 | 1969, 1973 | |

| 1974, 1981 | ||

| 1985, 1992 | ||

| 1982, 1993 | ||

| Sources:[11] | ||

Repeat winners (constructors)

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

Teams in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

| Wins | Constructor | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1961, 1963, 1965, 1966, 1968, 1978 | |

| 4 | 1971, 1976, 1977, 1979 | |

| 1981, 1985, 1992, 1993 | ||

| 2 | 1934, 1939 | |

| 1960, 1967 | ||

| 1973, 1975 | ||

| 1980, 1982 | ||

| 1970, 1983 | ||

| 1972, 1984 | ||

| Source:[11] | ||

Repeat winners (engine manufacturers)

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

Manufacturers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

| Wins | Manufacturer | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | 1968, 1969, 1970, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1975, 1981 | |

| 5 | 1960, 1961, 1963, 1965, 1966 | |

| 4 | 1971, 1976, 1977, 1979 | |

| 1980, 1982, 1992, 1993 | ||

| 3 | 1934, 1939, 1967 | |

| Source:[11] | ||

* Built by Cosworth

By year

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

References

- 1 2 Compiled from wire reports by Ken Paskman (24 October 1985). "AUTO RACING". Orlando Sentinel (3 STAR ed.). Orlando, Florida. p. B.2.

- ↑ "F1 abandons South Africa GP plans, Belgium set to stay". RacingNews365. 6 June 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ↑ Tom Prankerd. "A Second A Lap: GP '66 - XII South African Grand Prix". Archived from the original on 28 December 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ↑ "YouTube". www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ↑ The one that didn't count Retrieved from forix.autosport.com on 9 February 2010

- ↑ Martin, Gordon (17 September 1985). "The Apartheid Controversy Reaches Formula 1 Racing". San Francisco Chronicle (FINAL ed.). p. 63.

- ↑ Walker, Rob (February 1986). "Tiger, Tiger". Road & Track. Vol. 37, no. 6. New York. p. 122.

- 1 2 Los Angeles Times (Home 2 ed.). Newswire. 20 October 1985. p. 20.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "Will South Africa ever host an F1 Grand Prix again?". The South African. 16 April 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ "Kyalami Grand Prix officially non-starting over SA's stance on Russia". 6 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Higham, Peter (1995). "South African Grand Prix". The Guinness Guide to International Motor Racing. London, England: Motorbooks International. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-7603-0152-4 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ There were two South African Grands Prix in 1960. Reference

External links

| External videos | |

|---|---|

- ChicaneF1 Archived 5 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine