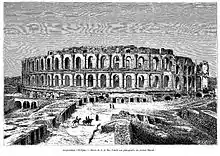

Thysdrus's huge amphitheater | |

Shown within Tunisia | |

| Location | Tunisia |

|---|---|

| Region | Mahdia Governorate |

| Coordinates | 35°17′24″N 10°42′29″E / 35.29000°N 10.70806°E |

Thysdrus was a Carthaginian town and Roman colony near present-day El Djem, Tunisia. Under the Romans, it was the center of olive oil production in the provinces of Africa and Byzacena and was quite prosperous. The surviving amphitheater is a World Heritage Site.

Name

The Punic name of the town was ŠṬPŠR (𐤔𐤈𐤐𐤔𐤓).[1] The Latin name Thysdrus has Berber roots.[2]

History

Thysdrus began as a small Carthaginian and Berber village.[2]

Following the Punic Wars, it was refounded as a Roman town[2] and probably received some of Julius Caesar's veterans as settlers in 45 BC. Punic culture remained long predominant, with the city minting bronze coins as late as Augustus with Punic inscriptions. Some bore Astarte's head obverse and a lyre reverse; others bore "Poseidon"'s head obverse and a capricorn reverse.[1]

Roman Africa was less arid than modern Tunisia, and Thysdrus and the surrounding lands in Byzacena were an important center of olive oil production and export. Its greatest importance occurred under the Severan dynasty in the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries. Septimius Severus was a native of Roman Africa and bestowed a great deal of imperial favor upon it. He raised Thysdrus to municipality status (Latin: municipium) with partial Roman citizenship.[3]

By the early 3rd century when its huge amphitheater was built, Thysdrus rivaled Hadrumetum (present-day Sousse) as the second city of Roman North Africa, after Carthage (near present-day Tunis). The city had even a huge racetrack (circus), nearly as large as the Circus Maximus at Rome and capable of accommodating about 30,000 spectators.

In AD 238, Thysdrus was at the center of a struggle to control the Roman Empire. After Maximinus Thrax killed Emperor Alexander Severus at Moguntiacum in Germania Inferior and assumed the throne,[4] his oppressive rule resulted in universal discontent. Maximinus's procurator in Africa, in particular, sought to extract the maximum level of taxation and fines possible, including falsifying charges against the local aristocracy.[5] A riot among the 50,000 Thysdrians ended with the death of the procurator, after which they turned to Gordian and demanded that he accept the dangerous honor of the imperial throne.[6] After protesting that he was too old for the position, he eventually yielded to the popular clamor of the Thysdrians and assumed both the purple and the epithet Africanus ("the African") on March 22.[7] According to Edward Gibbon:

An iniquitous sentence had been pronounced against some opulent youths of [Africa], the execution of which would have stripped them of far the greater part of their patrimony. (…) A respite of three days, obtained with difficulty from the rapacious treasurer, was employed in collecting from their estates a great number of slaves and peasants blindly devoted to the commands of their lords, and armed with the rustic weapons of clubs and axes. The leaders of the conspiracy, as they were admitted to the audience of the procurator, stabbed him with the daggers concealed under their garments, and, by the assistance of their tumultuary train, seized on the town of Thysdrus, and erected the standard of rebellion against the sovereign of the Roman empire. (...) Gordianus, their proconsul, and the object of their choice [as emperor], refused, with unfeigned reluctance, the dangerous honour, and begged with tears that they should suffer him to terminate in peace a long and innocent life, without staining his feeble age with civil blood. Their menaces compelled him to accept the Imperial purple, his only refuge indeed against the jealous cruelty of Maximin (...).[8]

Due to his advanced age, he insisted that his son M. Antonius Gordianus be acclaimed as his coruler.[6] A few days later, Gordian entered the city of Carthage with the overwhelming support of the population and local political leaders.[9] Meanwhile, in Rome, Maximinus's praetorian prefect was assassinated and the rebellion seemed to be successful.[10] Gordian in the meantime had sent an embassy to Rome under the leadership of P. Licinius Valerianus[11] to obtain the Senate's support for his rebellion.[10]

The senate confirmed the new emperor on 2 April and many of the provinces gladly sided with Gordian.[12]

Opposition would come from the neighboring province of Numidia.[13] Its governor Capelianus, a loyal supporter of Maximinus and a stalwart opponent of Gordian,[12] renewed his alliance to the emperor and invaded the province of Africa with the only legion stationed in the region and other veteran units.[14] Gordian II, at the head of a militia army of untrained soldiers mostly from Thysdrus and surroundings, lost the Battle of Carthage and was killed.[12] Gordian killed himself in his villa near Carthage by hanging himself with his belt.[15] The Gordians had "reigned" only thirty-six days.[16]

Following this abortive revolt, Capelianus's troops sacked Thysdrus. Thysdrus was subsequently raised to the level of a colony (colonia) by Gordian III in AD 244. It was the seat of a Christian diocese, which is included in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees.[17][18] All the same, it never really recovered.

Later history

Around 695, the Romano-Berber queen Kahina destroyed most of the olive trees of the Thysdrus area in her final attempt to stop the Arab invasion. She made her final stand at the amphitheater, but was defeated.

Similar to the Colosseum of Rome and to the theatre of Bosra, the amphitheatre was turned into a fortress where local tribes tried to check the Arab invasion of the region after the Byzantines had been defeated at Sufetula in 647. In 670 the Arabs founded Kairouan, forty miles north of Thysdrus, and made it the capital of the country. This fact, associated with the arrival of Arab nomadic tribes which led to the abandonment of farming, caused the decline of Thysdrus.

— Roberto Piperno[19]

In the next centuries, Thysdrus largely disappeared from the record, with a worsening arid climate apparently damaging its olive oil production. By the 10th century, many of Thysdrus's buildings had been dismantled for use in construction at Kairouan. In the 19th century, French colonizers found only a small village named El Djem, with a few hundred inhabitants living around the remains of the amphitheater and barely eking out enough production from their farms to survive.

Buildings

The Amphitheatre of El Jem was built around AD 238 and it is one of the best preserved stone Roman ruins in the world. It was named a World Heritage Site in 1979.

Religion

Thysdrus's bishops attended the councils of 393, 411, and 641. The Donatist schism had a hold in the city around 411.[20]

References

Citations

- 1 2 Head & al. (1911).

- 1 2 3 Thysdrus's History. (in Italian)

- ↑ JSTOR: Thysdrus

- ↑ Potter, pg. 167

- ↑ "Herodian 7.3 - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- 1 2 Southern, pg. 66

- ↑ Herodian, 7:5:8

- ↑ Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. I, Ch. 7

- ↑ Herodian, 7:6:2

- 1 2 Potter, pg. 169

- ↑ Zosimus, 1:11

- 1 2 3 Potter, pg. 170

- ↑ Southern, pg. 67

- ↑ Herodian, 7:9:3

- ↑ "Herodian 7.9 - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ↑ Meckler, Gordian I

- ↑ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 992

- ↑ Titular Episcopal See of Thysdrus at GCatholic.org.

- ↑ Thysdrus history and photos

- ↑ Stillwell, Richard. MacDonald, William L. McAlister, Marian Holland THYSDRUS (El Djem) Tunisia, The Princeton encyclopedia of classical sites. Princeton, N.J. Princeton University Press. 1976.

Bibliography

- Gibbon, Edward, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

- Head, Barclay; et al. (1911), "Byzacene", Historia Numorum (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 876.

- Herodian, Roman History, Book 7.

- Southern, Pat (2001), The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Syme, Ronald (1971), Emperors and Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Potter, David Stone (2004), The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180-395, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Birley, Anthony (2005), The Roman Government in Britain, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-925237-4.

- Zosimus, A New History.

%252C_Algeria_04966r.jpg.webp)