| |

Volubilis ruins | |

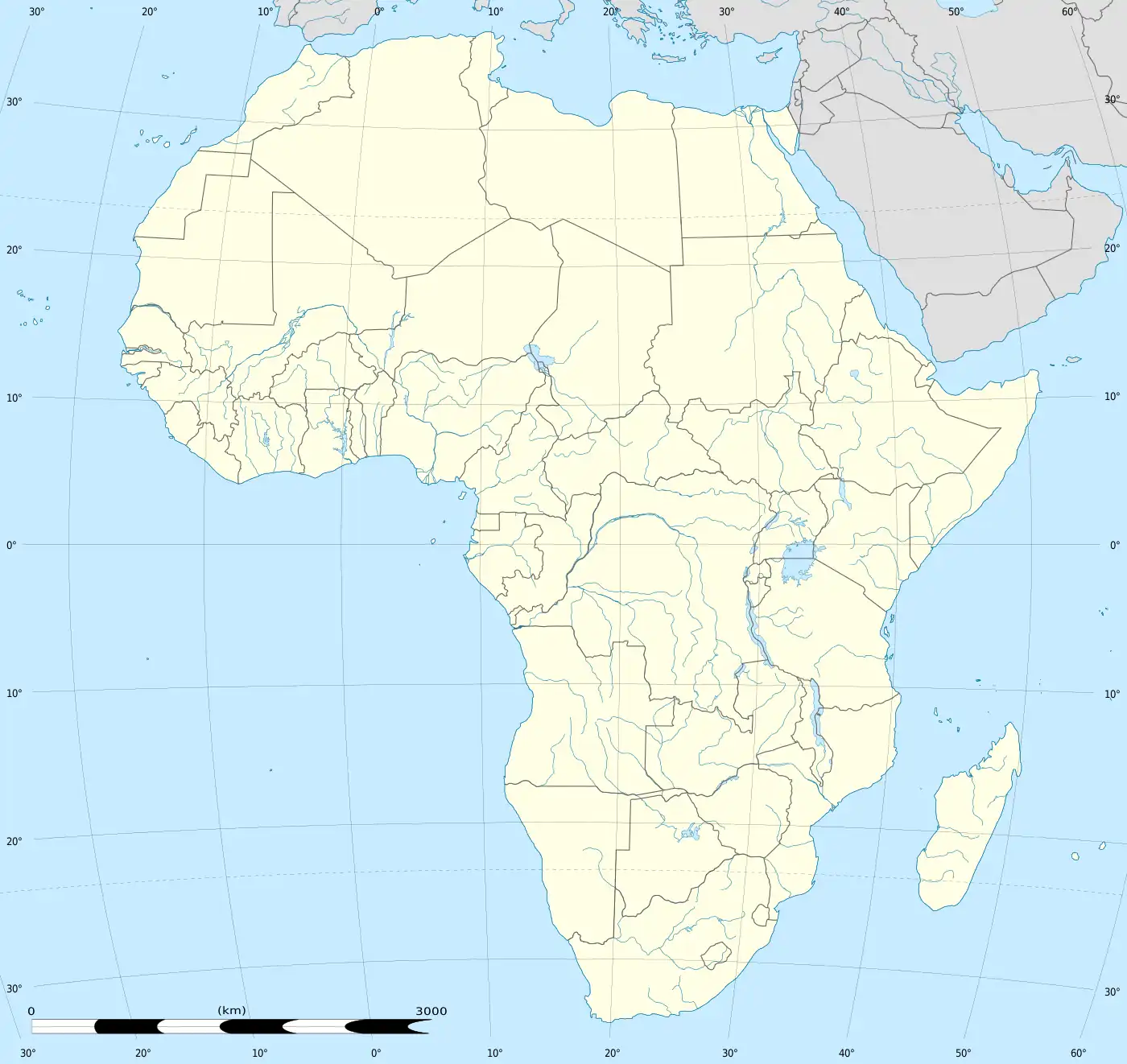

Shown within Morocco  Volubilis (Africa) | |

| Location | Meknès Prefecture, Fès-Meknès, Morocco |

|---|---|

| Region | Mauretania |

| Coordinates | 34°04′16″N 05°33′13″W / 34.07111°N 5.55361°W |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | 3rd century BC |

| Abandoned | 11th century AD |

| Cultures | Phoenician, Carthaginian, Mauretanian, Roman, Idrisids |

| Official name | Archaeological Site of Volubilis |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 1997 (21st session) |

| Reference no. | 836 |

| Region | North African States |

Volubilis (Latin pronunciation: [wɔˈɫuːbɪlɪs]; Arabic: وليلي, romanized: walīlī; Berber languages: ⵡⵍⵉⵍⵉ, romanized: wlili) is a partly-excavated Berber-Roman city in Morocco situated near the city of Meknes that may have been the capital of the Kingdom of Mauretania, at least from the time of King Juba II. Before Volubilis, the capital of the kingdom may have been at Gilda.[1][2]

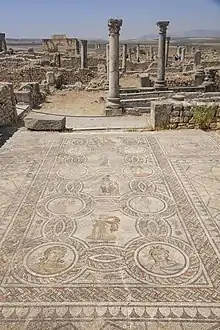

Built in a fertile agricultural area, it developed from the 3rd century BC onward as a Berber, then proto-Carthaginian, settlement before being the capital of the kingdom of Mauretania. It grew rapidly under Roman rule from the 1st century AD onward and expanded to cover about 42 hectares (100 acres) with a 2.6 km (1.6 mi) circuit of walls. The city gained a number of major public buildings in the 2nd century, including a basilica, temple and triumphal arch. Its prosperity, which was derived principally from olive growing, prompted the construction of many fine town-houses with large mosaic floors.

The city fell to local tribes around 285 and was never retaken by Rome because of its remoteness and indefensibility on the south-western border of the Roman Empire. It continued to be inhabited for at least another 700 years, first as a Latinised Christian community, then as an early Islamic settlement. In the late 8th century it became the seat of Idris ibn Abdallah, the founder of the Idrisid dynasty of Morocco. By the 11th century Volubilis had been abandoned after the seat of power was relocated to Fes. Much of the local population was transferred to the new town of Moulay Idriss Zerhoun, about 5 km (3.1 mi) from Volubilis.

The ruins remained substantially intact until they were devastated by an earthquake in the mid-18th century and subsequently looted by Moroccan rulers seeking stone for building Meknes. It was not until the latter part of the 19th century that the site was definitively identified as that of the ancient city of Volubilis. During and after the period of French rule over Morocco, about half of the site was excavated, revealing many fine mosaics, and some of the more prominent public buildings and high-status houses were restored or reconstructed. Today it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, listed for being "an exceptionally well preserved example of a large Roman colonial town on the fringes of the Empire".

Name

The origins of its name are unknown but may be a Latinisation of the Amazigh word Walilt, meaning oleander, which grows along the sides of the valley.[3] It could also be seen as a direct translation of the Amazigh name if this one was related to the root WLLY meaning "to turn, to spin".[4]

The Lewis & Short Latin dictionary gives the Latin meaning of "volubilis" as "that [which] is turned round or (more freq.) that [which] turns itself round, turning, spinning, whirling, circling, rolling, revolving."[5] The word is mentioned in Horace's Epistles (I, 2, 43): labitur, et labetur in omne volubilis aevum ("It flows and will flow, swirling on forever.")[5][6] In Classical Latin, the "v" in "volubilis" was pronounced like a "w", making the pronunciation closer to modern Amazigh and Arabic pronunciations.[7]

Charles-Joseph Tissot (1828–1884) discovered that what some sources in Arabic referred to as "Qasr Fara'on" (قصر فرعون Pharaoh's Palace) corresponded with Volubilis.[8] This term is still used nowadays by the locals, sometimes shortened as لقصر El Ksar, meaning "The Palace".[9]

Foundation and Roman occupation

Built on a shallow slope below the Zerhoun mountain, Volubilis stands on a ridge above the valley of Khoumane (Khuman) where it is met by a small tributary stream called the Fertassa.[10] It overlooks a rolling fertile alluvial plain north of the modern city of Meknes.[10] The area around Volubilis has been inhabited at least since the Late Atlantic Neolithic, some 5,000 years ago; archaeological excavations at the site have found Neolithic pottery of design comparable to pieces found in Iberia.[11] By the third century BC, the Carthaginians had a presence there, as evidenced by the remains of a temple to the Punic god Baal and finds of pottery and stones inscribed in the Phoenician language.[12]

The city lay within the kingdom of Mauretania, which became a Roman client state following the fall of Carthage in 146 BC.[12] The Punic influence lasted for a considerable time afterwards, as the city's magistrates retained the Carthaginian title of suffete long after the end of Punic rule.[14] Juba II of Numidia was placed on the Mauretanian throne by Augustus in 25 BC and turned his attention to building a royal capital at Volubilis.[15] Educated in Rome and married to Cleopatra Selene II, the daughter of Mark Antony and Cleopatra, Juba and his son Ptolemy were thoroughly Romanised kings, although of Berber ancestry; their preference for Roman art and architecture was clearly reflected in the city's design.[12]

After Claudius annexed Mauretania in 44 AD, the city grew substantially due to its wealth and prosperity, derived from the fertile lands of the province which produced valuable export commodities such as grain, olive oil and wild animals for gladiatorial spectacles. At its peak in the late 2nd century, Volubilis had around 20,000 inhabitants – a very substantial population for a Roman provincial town[16] – and the surrounding region was also well inhabited, to judge from over 50 villas discovered in the area.[17] It was mentioned by the 1st century AD geographer Pomponius Mela, who described it in his work De situ orbis libri III as one of "the wealthiest cities, albeit the wealthiest among small ones" in Mauretania.[18] It is also mentioned by Pliny the Elder, and the 2nd century Antonine Itinerary refers to its location and names it as Volubilis Colonia.[19] Its population was dominated by Romanised Berbers.[20]

.jpg.webp)

The city remained loyal to Rome despite a revolt in 40–44 AD led by one of Ptolemy's freedmen, Aedemon, and its inhabitants were rewarded with grants of citizenship and a ten-year exemption from taxes.[17] The city was raised to the status of a municipium and its system of governance was overhauled, with the Punic-style suffetes replaced by annually elected duumvirs, or pairs of magistrates.[20] However, the city's position was always tenuous; it was located on the south-eastern edge of the province, facing hostile and increasingly powerful Berber tribes. A ring of five forts located at the modern hamlets of Aïn Schkor, Bled el Gaada, Sidi Moussa, Sidi Said and Bled Takourart (ancient Tocolosida) were constructed to bolster the city's defence.[17] Sidi Said was the base for the Cohors IV Gallorum equitata, an auxiliary cavalry unit from Gaul, while Aïn Schkor housed Hispanic and Belgic cohorts. Sidi Moussa was the location of a cohort of Parthians, and Gallic and Syrian cavalry were based at Toscolosida.[21] Rising tensions in the region near the end of the 2nd century led the emperor Marcus Aurelius to order the construction of a 2.5 km (1.6 mi) circuit of walls with eight gates and 40 towers.[17] Volubilis was connected by road to Lixus and Tingis (capital city of the Roman province of Mauretania Tingitana, modern Tangier) but had no eastwards connections with the neighbouring province of Mauretania Caesariensis, as the territory of the Berber Baquates tribe lay in between.[17] A Jewish community existed in Volubilis in the third century, as evident from several Hebrew, Greek and Latin funeral inscriptions and Menorah-shaped lamps. It is the most south-western location where ancient Hebrew inscription has been found.[22]

Rome's control over the city ended following the chaos of the Crisis of the Third Century, when the empire nearly disintegrated as a series of generals seized and lost power through civil wars, palace coups and assassinations. Around 280, Roman rule collapsed in much of Mauretania and was never re-established. In 285, the emperor Diocletian reorganised what was left of the province to retain only the coastal strip between Lixus, Tingis and Septa (modern Ceuta). Although a Roman army was based in Tingis, it was decided that it would simply be too expensive to mount a reconquest of a vulnerable border region.[17] Occupation of the city continued, however, as fine mosaics such as that of a chariot race conducted by animals in the House of Venus can not have been created earlier than the fourth century. The end of the Roman city probably came in the form of an earthquake towards the end of the century, which buried numerous bronze statues in the wreckage of the houses.[23]

After the Romans

Volubilis continued to be inhabited for centuries after the end of Roman control. It was certainly reoccupied by the Eastern Roman Empire in the sixth and seventh century, when three Christian inscriptions are dated by the provincial year.[24] By the time the Arabs had arrived in 708,[16] the city's name was changed to Oualila or Walīlī, and it was inhabited by the Awraba, a Berber tribe that originated in Libya. Much of the city centre had been abandoned and was turned into a cemetery, while the centre of habitation had moved to the southwest of the city, where a new wall was built to contain the abridged Roman town.[25]

Volubilis remained the capital of the region well into the Islamic period. Islamic coins dating to the 8th century have been found on the site, attesting to the arrival of Islam in this part of Morocco.[20] They are concentrated outside the city walls, which suggests that Arab settlement remained distinct from the Berber settlement inside them. It was here that Moulay Idriss established the Idrisid dynasty of Morocco in 787-8. A direct descendant of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, he escaped to Morocco from Syria following the Battle of Fakhkh in 787. He was proclaimed "imam" in Volubilis, occupied by the Awraba, under Ishaq ibn Mohammad. He married Kanza, from the Awraba, and fathered a son, Idris II, who was proclaimed imam in Volubilis. He, too, lived outside the walls of the city, along the banks of the Wadi Khoumane, where a complex has recently been excavated that may be identified with his headquarters.[26] Idriss I conquered most of Northern Morocco during the three years of his reign, founding the city of Fes. He was assassinated in Volubilis in 791 on the orders of the caliph of Baghdad, Harun al-Rashid.[27][20] On his majority Idriss II removed to Fes which served as his new capital, depriving Volubilis of its last vestiges of political significance.[27]

A Muslim group known as the Rabedis, who had revolted in Córdoba in Al-Andalus (Andalusia in modern Spain), resettled at Volubilis in 818.[20] Although people continued to live in Volubilis for several more centuries, it was probably almost deserted by the 14th century. Leo Africanus describes its walls and gates, as well as the tomb of Idris, guarded only by two or three castles.[28] His body was subsequently removed to Moulay Idriss Zerhoun, 3 km (1.9 mi), where a great mausoleum was built for it. The name of the city was forgotten and it was termed Ksar Faraoun, or the "Pharaoh's Castle", by the local people, alluding to a legend that the ancient Egyptians had built it.[29] Nonetheless, some of its buildings remained standing, albeit ruined, until as late as the 17th century when Moulay Ismail ransacked the site to provide building material for his new imperial capital at Meknes. An earthquake in 1755 caused further severe destruction. However, English antiquarian John Windus had sketched the site in 1722.[27] In his 1725 book A Journey to Mequinez, Windus described the scene:

One building seems to be part of a triumphal arch, there being several broken stones that bear inscriptions, lying in the rubbish underneath, which were fixed higher than any part now standing. It is 56 feet long and 15 thick, both sides exactly alike, built with very hard stones, about a yard in length and half a yard thick. The arch is 20 feet wide and about 26 high. The inscriptions are upon large flat stones, which, when entire, were about five feet long, and three broad, and the letters on them above 6 inches long. A bust lay a little way off, very much defaced, and was the only thing to be found that represented life, except the shape of a foot seen under the lower part of a garment, in the niche on the other side of the arch. About 100 yards from the arch stands a good part of the front of a large square building, which is 140 feet long and about 60 high; part of the four corners are yet standing, but very little remains, except these of the front. Round the hill may be seen the foundation of a wall about two miles in circumference, which inclosed these buildings; on the inside of which lie scattered, all over, a great many stones of the same size the arch is built with, but hardly one stone left upon another. The arch, which stood about half a mile from the other buildings, seemed to have been a gateway, and was just high enough to admit a man to pass through on horseback.[30]

Visiting 95 years later in 1820, after the 1755 earthquake had flattened the few buildings left standing, James Gray Jackson wrote:

Half an hour's journey after leaving the sanctuary of Muley Dris Zerone, and at the foot of Atlas, I perceived to the left of the road, magnificent and massive ruins. The country, for miles round, is covered with broken columns of white marble. There were still standing two porticoes about 30 feet high and 12 wide, the top composed of one entire stone. I attempted to take a view of these immense ruins, which have furnished marble for the imperial palaces at Mequinas and Tafilelt; but I was obliged to desist, seeing some persons of the sanctuary following the cavalcade. Pots and kettles of gold and silver coins are continually dug up from these ruins. The country, however, abounds with serpents, and we saw many scorpions under the stones that my conductor turned up. These ruins are said by the Africans to have been built by one of the Pharaohs: they are called Kasser Farawan.[31]

- Volubilis before its excavation and restoration

The ruins of the triumphal arch, photographed in 1887 by Henri Poisson de La Martinière

The ruins of the triumphal arch, photographed in 1887 by Henri Poisson de La Martinière Remnants of the basilica as seen in 1887 before its later restoration

Remnants of the basilica as seen in 1887 before its later restoration

Walter Burton Harris, a writer for The Times, visited Volubilis during his travels in Morocco between 1887 and 1889, after the site had been identified by French archaeologists but before any serious excavations or restorations had begun. He wrote:

There is not very much remains standing of the ruins; two archways, each of great size, and in moderately good preservation, alone tell of the grandeur of the old city, while acres and acres of land are strewn with monuments and broken sculpture. A few isolated pillars also remain, and an immense drain or aqueduct, not unlike the Cloaca Maxima at Rome, opens on to the little river below.[32]

Excavation, restoration and UNESCO listing

Much of Volubilis was excavated by the French during their rule over French Morocco between 1912 and 1955, but the excavations at the site began decades earlier. From 1830, when the French conquest of Algeria began the process of extending French rule over much of northern, western and central Africa, archaeology was closely associated with French colonialism. The French army undertook scientific explorations as early as the 1830s and by the 1850s it was fashionable for French army officers to investigate Roman remains during their leave and spare time. By the late 19th century French archaeologists were undertaking an intensive effort to uncover northwest Africa's pre-Islamic past through excavations and restorations of archaeological sites.[33]

The French had a very different conception of historic preservation to that of the Moroccan Muslims. As the historian Gwendolyn Wright puts it, "The Islamic sense of history and architecture found the concept of setting off monuments entirely foreign", which "gave the French proof of the conviction that only they could fully appreciate the Moroccan past and its beauty." Emile Pauty of the Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines criticised the Muslims for taking the view that "the passage of time is nothing" and charged them with "let[ting] their monuments fall into ruin with as much indifference as they once showed ardour in building them."[34]

The French programme of excavation at Volubilis and other sites in French-controlled North Africa (in Algeria and Tunisia) had a strong ideological component. Archaeology at Roman sites was used as an instrument of colonialist policy, to make a connection between the ancient Roman past and the new "Latin" societies that the French were building in North Africa. The programme involved clearing modern structures built on ancient sites, excavating Roman towns and villas and reconstructing major civic structures such as triumphal arches. Ruined cities, such as Timgad in Algeria, were excavated and cleared on a massive scale. The remains were intended to serve, as one writer has put it, as "the witness to an impulse towards Romanization".[35]

This theme resonated with other visitors to the site. The American writer Edith Wharton visited in 1920 and highlighted what she saw as the contrast between "two dominations look[ing] at each other across the valley", the ruins of Volubilis and "the conical white town of Moulay Idriss, the Sacred City of Morocco". She saw the dead city as representing "a system, an order, a social conception that still runs through all our modern ways." In contrast, she saw the still very much alive town of Moulay Idriss as "more dead and sucked back into an unintelligible past than any broken architrave of Greece or Rome."[36] As Sarah Bird Wright of the University of Richmond puts it, Wharton saw Volubilis as a symbol of civilisation and Moulay Idriss as one of barbarism; the subtext is that "in ransacking the Roman outpost, Islam destroyed its only chance to build a civilised society".[37] Fortunately for Morocco, "the political stability which France is helping them to acquire will at last give their higher qualities time for fruition"[38]—very much the theme that the French colonial authorities wanted to get across.[39] Hilaire Belloc, too, spoke of his impression being "rather one of history and of contrast. Here you see how completely the new religion of Islam flooded and drowned the classical and Christian tradition."[40]

The first excavations at Volubilis were carried out by the French archaeologist Henri de la Martinière between 1887 and 1892.[41] In 1915 Hubert Lyautey, the military governor of French Morocco, commissioned the French archaeologists Marcel and Jane Dieulafoy to carry out excavations in Volubilis. Although Jane's ill-health meant that they were unable to carry out the programme of work that they drew up for Lyautey,[42] the work went ahead anyway under Louis Chatelain.[41] The French archaeologists were assisted by thousands of German prisoners of war who had been captured during First World War and loaned to the excavators by Lyautey.[33] The excavations continued on and off until 1941, when the Second World War forced a halt.[41]

Following the war, excavations resumed under the French and Moroccan authorities (following Morocco's independence in 1955) and a programme of restoration and reconstruction began. The Arch of Caracalla had already been restored in 1930–34. It was followed by the Capitoline Temple in 1962, the basilica in 1965–67 and the Tingis Gate in 1967. A number of mosaics and houses underwent conservation and restoration in 1952–55. In recent years, one of the olive-oil production workshops in the southern end of the city has been restored and furnished with a replica Roman oil press.[43] These restorations have not been without controversy; a review carried out for UNESCO in 1997 reported that "some of the reconstructions, such as those on the triumphal arch, the capitolium, and the oil-pressing workshop, are radical and at the limit of currently accepted practice."[43]

From 2000 excavations carried out by University College London and the Moroccan Institut National des Sciences de l'Archéologie et du Patrimoine under the direction of Elizabeth Fentress, Gaetano Palumbo and Hassan Limane revealed what should probably be interpreted as the headquarters of Idris I just below the walls of the Roman town to the west of the ancient city centre. Excavations within the walls also revealed a section of the early medieval town.[44] Today, many artefacts found at Volubilis can be seen on display in the Rabat Archaeological Museum.

UNESCO listed Volubilis as a World Heritage Site in 1997. In the 1980s, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) organised three conferences to assess possible nominations to the World Heritage List for sites in North Africa. It was unanimously agreed that Volubilis was a good candidate for the list and in 1997 ICOMOS recommended that it be inscribed as "an exceptionally well preserved example of a large Roman colonial town on the fringes of the Empire",[45] which UNESCO accepted.

City layout and infrastructure

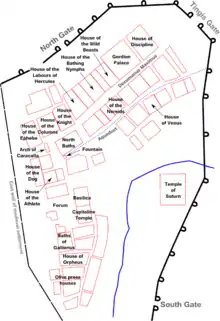

Prior to the Roman occupation, Volubilis covered an area of about 12 hectares (30 acres), built on a V-shaped ridge between the Fertassa and Khoumane wadis on a roughly north–south axis. It was developed on a fairly regular pattern typical of Phoenician/Carthaginian settlements and was enclosed by a set of walls.[46] Under the Romans, the city was expanded considerably on a northeast–southwest axis, increasing in size to about 42 hectares (100 acres). Most of the city's public buildings were constructed in the older part of the city. The grand houses for which Volubilis is famous are in the newer part, behind the Decumanus Maximus (main street), which bisected the Roman-era part of the city.[41] The decumanus was paved, with footways on either side, and was lined with arcaded porticoes on either sides, behind which were dozens of shops.[47] The Arch of Caracalla marks the point at which the old and new cities merge. After the aqueduct fell into disrepair with the end of the Roman occupation, a new residential area was constructed to the west near the Wadi Khoumane.[46]

The city was supplied with water by an aqueduct that ran from a spring in the hills behind the city.[48] The aqueduct may have been constructed around 60–80 AD and was subsequently reconstructed on several occasions.[49] An elaborate network of channels fed houses and the public baths from the municipal supply and a series of drains carried sewage and waste away to the river to be flushed.[48] The aqueduct ran under the Decumanus Secundus, a street that ran parallel with the Decumanus Maximus, and terminated at a large fountain in the city centre near the Arch of Caracalla.[12]

- Infrastructure in Volubilis

The Decumanus Maximus, looking north-east

The Decumanus Maximus, looking north-east The Tingis Gate, looking back down the Decumanus Maximus

The Tingis Gate, looking back down the Decumanus Maximus Interior of the North Baths, fed by the aqueduct

Interior of the North Baths, fed by the aqueduct

Most of the original pre-Roman city wall was built over or destroyed, but a 77-metre (250 ft) stretch of the original wall, which was made of mud bricks on a stone foundation, can still be seen near the tumulus.[20][49] The Roman city walls stretch for 2.6 km (1.6 mi) and average 1.6 m (5.2 ft) thick. Built of rubble masonry and ashlar, they are mostly still extant.[41][49] The full circuit of walls had 34 towers, spaced at intervals of about one every 50 metres (160 ft), and six main gates that were flanked by towers.[47] A part of the eastern wall has been reconstructed to a height of 1.5 metres (4.9 ft).[41] The Tingis Gate, also reconstructed, marks the northern-eastern entrance to Volubilis.[46] It was constructed in 168/169 AD – the date is known due to the discovery of a coin of that year that was deliberately embedded in the gate's stonework by its builders.[47]

An early medieval wall stands to the west of the Arch of Caracalla; it was built after the end of the Roman occupation, apparently some time in the 5th or 6th centuries, to protect the eastern side of the city's new residential area. It was oriented in a north–south direction and was constructed using stone looted from ruined buildings elsewhere in the abandoned areas of the city.[17][49]

Commerce

During Roman times, Volubilis was a major producer of olive oil. The remains of buildings dedicated to olive pressing are still readily visible, as are the remains of the original presses and olive mills. One such building has been reconstructed with a full-size replica of a Roman olive press.[50] Olive oil was central to the life of the city, as it was not just a foodstuff but was also used for lamps, bathing and medicines, while the pressed olives were fed to animals or dried out and used as fuel for the bathhouses. For this reason, even some of the grandest mansions had their own olive presses.[51] Fifty-eight oil-pressing complexes have so far been discovered in Volubilis. They housed a standard set of elements: a mill, used to crush the olives, a decantation basin to catch the oil from pressed olives, and a press that comprised a counterweight, a prelum or cross-bar and the wooden supports within which the prelum was fixed. The olives were first crushed into a paste, then put into woven baskets that were subjected to pressing. The olive oil ran out into the decantation basin, to which water was periodically added to make the lighter oil float to the surface. This was then scooped out of the basin and poured into amphorae.[49] There is also substantial evidence of the city being a lively commercial centre. No fewer than 121 shops have been identified so far, many of them bakeries,[52] and judging from the number of bronzes found at the site it may also have been a centre for the production or distribution of bronze artworks.[53]

Notable buildings

Although only about half of Volubilis has been excavated, a number of prominent public buildings are still visible and some, notably a basilica and a triumphal arch, have been reconstructed. Many private buildings, including the mansions of the city's elite, have also been uncovered. They are especially notable for the fine mosaics that have been discovered in a number of buildings and which are still in situ in the houses where they were laid.[16] The buildings were mostly made from locally quarried grey-blue limestone.[41] Very little remains of the original Punic settlement, as it lies under the later Roman buildings.[20]

A large tumulus of uncertain origin and purpose stands approximately in the middle of the excavated area, between the old and new parts of the city. Various theories have been advanced to explain it, such as that it was a burial site, a religious structure of some kind, a funerary monument or a monument to a Roman victory. However, these remain unproven hypotheses.[20]

Public buildings

Two major public buildings are readily visible at the centre of the city – the basilica and the Capitoline Temple. The basilica was used for the administration of justice and the governance of the city. Completed during the reign of Macrinus in the early 3rd century, it is one of the finest Roman basilicas in Africa[54] and is probably modelled on the one at Leptis Magna in Libya.[55] The building is 42.2 m (138 ft) long by 22.3 m (73 ft) wide and originally had two storeys.[49] Its interior is dominated by two rows of columns framing the apses at each end of the building where the magistrates sat. The outer wall of the basilica, which is faced with columns, overlooks the forum where markets were held. Small temples and public offices also lined the 1,300 m2 (14,000 sq ft) forum,[54] which would have been full of statues of emperors and local dignitaries, of which only the pedestals now remain.[49] Not much is known about the public buildings which existed in Volubilis prior to the start of the 3rd century, as the buildings currently visible were built on the foundations of earlier structures.[56]

The Capitoline Temple stands behind the basilica within what would originally have been an arcaded courtyard. An altar stands in the courtyard in front of 13 steps leading up to the Corinthian-columned temple,[54] which had a single cella.[49] The building was of great importance to civic life as it was dedicated to the three chief divinities of the Roman state, Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. Civic assemblies were held in front of the temple to beseech the aid of the gods or to thank them for successes in major civic undertakings such as fighting wars.[54] The layout of the temple, facing the back wall of the basilica, is somewhat unusual and it has been suggested that it may have been built on top of an existing shrine.[57] An inscription found in 1924 records that it was reconstructed in 218. It was partly restored in 1955 and given a more substantial restoration in 1962, reconstructing 10 of the 13 steps, the walls of the cella and the columns. There were four more small shrines within the temple precinct, one of which was dedicated to Venus.[49]

There were five other temples in the city, of which the most notable is the so-called "Temple of Saturn" that stood on the eastern side of Volubilis.[49] It appears to have been built on top of, or converted from, an earlier Punic temple, which may have been dedicated to Baal.[58] It is a sanctuary with a surrounding wall and a three-sided portico. In its interior was a small temple with a cella built on a shallow podium.[49] The temple's traditional identification with Saturn is purely hypothetical and has not generally been accepted.[59]

- Public buildings in Volubilis

Exterior of the Basilica at Volubilis

Exterior of the Basilica at Volubilis Interior of the Basilica

Interior of the Basilica The Capitoline Temple

The Capitoline Temple

Volubilis also possessed at least three sets of public baths. Some mosaics can still be seen in the Baths of Gallienus, redecorated by that emperor in the 260s to become the city's most lavish baths.[51] The nearby north baths were the largest in the city, covering an area of about 1,500 m2 (16,000 sq ft). They were possibly built in the time of Hadrian.[57]

Triumphal arch

The Arch of Caracalla is one of Volubilis' most distinctive sights, situated at the end of the city's main street, the Decumanus Maximus. Although it is not architecturally outstanding,[50] the triumphal arch forms a striking visual contrast with the smaller Tingis Gate at the far end of the decumanus. It was built in 217 by the city's governor, Marcus Aurelius Sebastenus, to honour the emperor Caracalla and his mother Julia Domna. Caracalla was himself a North African and had recently extended Roman citizenship to the inhabitants of Rome's provinces. However, by the time the arch was finished both Caracalla and Julia had been murdered by a usurper.[57]

The arch is constructed from local stone and was originally topped by a bronze chariot pulled by six horses. Statues of nymphs poured water into carved marble basins at the foot of the arch. Caracalla and Julia Domna were represented on medallion busts, though these have been defaced. The monument was reconstructed by the French between 1930 and 1934.[57] However, the restoration is incomplete and of disputed accuracy. The inscription on the top of the arch was reconstructed from the fragments noticed by Windus in 1722, which had been scattered on the ground in front of the arch.[49]

- The Arch of Caracalla at Volubilis

North side of the Arch of Caracalla

North side of the Arch of Caracalla Dedicatory inscription

Dedicatory inscription South side of the Arch of Caracalla

South side of the Arch of Caracalla

The inscription reads (after the abbreviations have been expanded):

IMPERATORI CAESARI MARCO AVRELLIO ANTONINO PIO FELICI AVGVSTO PARTHICO MAXIMO BRITTANICO MAXIMO GERMANICO MAXIMO

PONTIFICI MAXIMO TRIBVNITIA POTESTATE XX IMPERATORI IIII CONSVLI IIII PATRI PATRIAE PROCONSVLI ET IVLIAE AVGVSTAE PIAE FELICI MATRI

AVGVSTI ET CASTRORVM ET SENATVS ET PATRIAE RESPVBLICA VOLVBILITANORVM OB SINGVLAREM EIVS

ERGA VNIVERSOS ET NOVAM SVPRA OMNES RETRO PRINCIPES INDVLGENTIAM ARCVM

CVM SEIVGIBVS ET ORNAMENTIS OMNIBVS INCOHANTE ET DEDICANTE MARCO AVRELLIOSEBASTENO PROCVRATORE AVGVSTI DEVOTISSIMO NVMINI EIVS A SOLO FACIENDVM CVRAVIT

or, in translation:

For the emperor Caesar, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus [Caracalla], the pious, fortunate Augustus, greatest victor in Parthia, greatest victor in Britain, greatest victor in Germany, Pontifex Maximus, holding tribunician power for the twentieth time, Emperor for the fourth time, Consul for the fourth time, Father of the Country, Proconsul, and for Julia Augusta [Julia Domna], the pious, fortunate mother of the camp and the Senate and the country, because of his exceptional and new kindness towards all, which is greater than that of the principes that came before, the Republic of the Volubilitans took care to have this arch made from the ground up, including a chariot drawn by six horses and all the ornaments, with Marcus Aurelius Sebastenus, procurator, who is most deeply devoted to the divinity of Augustus, initiating and dedicating it.

Houses and palaces

The houses found at Volubilis range from richly decorated mansions to simple two-room mud-brick structures used by the city's poorer inhabitants.[56] The city's considerable wealth is attested by the elaborate design of the houses of the wealthy, some of which have large mosaics still in situ. They have been named by archaeologists after their principal mosaics (or other finds):

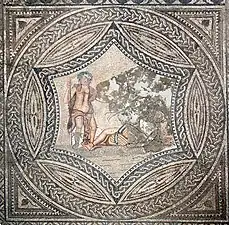

- The House of Orpheus in the southern part of the city thus takes its name from the large Orpheus mosaic, showing the god playing his harp to an audience of trees, animals and birds.[51] As Paul MacKendrick puts it, the mosaic is rather artlessly executed, as the animals are all of different sizes and face in different directions with no relationship to Orpheus. It appears that the mosaicist simply copied patterns from a book without attempting to integrate the different elements.[47] The mosaic is situated in the triclinium, the dining room, where the diners would have reclined on couches set against the walls and admired the central mosaic. Other mosaics can be seen in the atrium, which has a depiction of Amphitrite in a chariot pulled by a seahorse and accompanied by other sea creatures, and in the bathing rooms. One room off the main courtyard has a mosaic of a dolphin, considered by the Romans to be a lucky animal.[51]

- The House of the Athlete or Desultor, located near the forum, contains a humorous mosaic of an athlete or acrobat riding a donkey back to front while holding a cup in his outstretched hand.[57] It may possibly represent Silenus.[60] The most prestigious houses in the city were situated adjoining the Decumanus Maximus, behind rows of shops that lined the street under an arcade. They were entered from side streets between the shops.

- The House of the Ephebe was named after a bronze statue found there. It has a prominent interior courtyard leading to a number of public rooms decorated with mosaics, including a depiction of Bacchus in a chariot being drawn by leopards.

- The House of the Knight next door also has a mosaic of Bacchus, this time shown coming across the sleeping Ariadne, who later bore him six children.[57] The house takes its name from a bronze statue of a rider found here in 1918 that is now on display in the archaeological museum in Rabat.[61] It was a large building, with an area of about 1,700 m2 (18,000 sq ft), and incorporated a substantial area dedicated to commercial activities including eight or nine shops opening onto the road and a large olive-pressing complex.[62]

- Mosaics in Volubilis

Mosaic of Bacchus encountering the sleeping Ariadne from the House of the Knight

Mosaic of Bacchus encountering the sleeping Ariadne from the House of the Knight Mosaic of the Four Seasons in situ in the House of the Labours of Hercules

Mosaic of the Four Seasons in situ in the House of the Labours of Hercules Mosaic of the Labours of Hercules

Mosaic of the Labours of Hercules Mosaic of Diana and her nymph surprised by Actaeon while bathing, from the House of Venus

Mosaic of Diana and her nymph surprised by Actaeon while bathing, from the House of Venus_(4).jpg.webp) Mosaic of Diana in the House of Venus

Mosaic of Diana in the House of Venus Mosaic of the Labours of Hercules

Mosaic of the Labours of Hercules Mosaic in the House of the Athlete

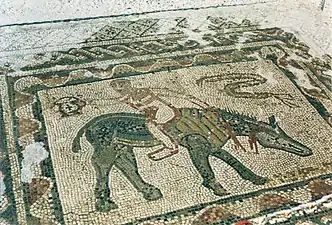

Mosaic in the House of the Athlete_(5).jpg.webp) Mosaic in the House of Wild Beasts

Mosaic in the House of Wild Beasts

- The House of the Labours of Hercules is named for the mosaic depicting the twelve tasks that the demigod had to perform as penance for killing his wife and children. It is thought to have been created during the reign of the emperor Commodus, who identified himself with Hercules. Jupiter, his lover Ganymede and the four seasons are depicted in another mosaic in the house.[63] The house was of palatial size, with 41 rooms covering an area of 2,000 m2 (22,000 sq ft).

- A building dubbed the Gordian Palace is located further up the Decumanus Maximus. It was the largest building in the city and was probably the residence of the governor, rather than the emperor Gordian III; it was rebuilt during Gordian's reign in the mid-3rd century. It combined two separate houses to create a complex of 74 rooms with courtyards and private bathhouses serving both domestic and official functions.[64] It also incorporated a colonnaded front with a dozen shops behind the colonnade, and an oil factory consisting of three oil presses and an oil store in the north-east corner of the complex.[53] The decoration of the Gordian Palace is today quite plain with only a few scanty mosaics remaining.[64] Despite its presumed high status, the floors seem to have been mostly rendered with opus sectile rather than decorated with mosaics.[52] Inscriptions found in the palace testify to the city's decline and eventual fall. They record a series of treaties reached with the local Berber chieftains, increasing in number as the city became more vulnerable and the tribesmen pressed harder. By the time of the final treaty, just a few years before the fall of the city, the chieftains were being treated as virtual equals of Rome – an indication of how much Roman power in the area had declined.[64] The last two inscribed altars, from 277 and 280, refer to a foederata et diuturna pax (a "federated and lasting peace"), though this proved to be a forlorn hope, as Volubilis fell soon afterwards.[21]

- The House of Venus, towards the eastern side of the city under a prominent cypress tree, was one of the most luxurious residences in the city. It had a set of private baths and a richly decorated interior, with fine mosaics dating from the 2nd century AD showing animal and mythological scenes. There were mosaics in seven corridors and eight rooms.[52] The central courtyard has a fanciful mosaic depicting racing chariots in a hippodrome, drawn by teams of peacocks, geese and ducks. The mosaic of Venus for which the house is named has been removed to Tangier, but in the next-door room is a still-extant mosaic showing Diana and a companion nymph being surprised by Actaeon while bathing. Actaeon is depicted with horns beginning to sprout from his head as he is transformed by the angry goddess into a stag, before being chased down and killed by his own hunting dogs.[65] The house appears to have been destroyed some time after the city's fall around 280; a mosaic depicting Cupids feeding birds with grain has been charred by what appears to have been a fire burning directly on top of it, perhaps resulting from the building being taken over by squatters who used the mosaic as the site of a hearth.[53]

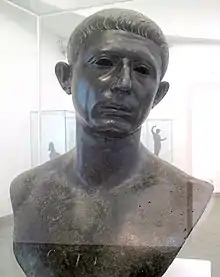

The same building was also the site of the discovery in 1918 of a bronze bust of outstanding quality depicting Cato the Younger. One of the most notable artefacts discovered at Volubilis, it is now on display in the Archaeological Museum in Rabat. It was still on its original pedestal when it was found by archaeologists. The bust has been dated to the time of Nero or Vespasian and may be a copy of a bust created in Cato's lifetime or shortly thereafter. Its inscription identifies its subject as the orator.[52] Another outstanding bust, depicting a Hellenistic prince, was discovered in a bakery across the street. It seems to have been made at the same time as the Cato bust and may well have come from the House of Venus, where an empty pedestal in another room suggests that the Cato had a companion piece. The bust, which is also on display in Rabat, is usually identified as Juba II but other possibilities include Hiero II of Syracuse, Cleomenes III of Sparta, Juba I or Hannibal.[66]

Headquarters of Idris I

Just outside the walls of the city, on the floodplain of the Oued Khoumane, was found a series of interlocking courtyard buildings, of which the largest contained a hammam, or bath. This is an L-shaped structure, with a cold room paved with flagstones and benches running along the sides. At the end is found a plunge pool with three steps leading into it. From the cold room one moved to a vestibule at the corner of the building, decorated with a relief of a shield taken from the Arch of Caracalla. From there, one moved into the warm room, still covered by a vault, and finally into the hot room. The vault of this has now been restored, but it is possible to see the channels in the floor through which the hot air passed. Beyond this a furnace heated the room, as well as the hot water which would have flowed into basins in the corners. The courtyard of which this hammam formed the western limit was large, and contained numerous large silos for grain storage. To the south of this courtyard was one evidently designed for reception, with long narrow rooms to the east and west, one of which was painted red, with a low bench or divan at one end. Further south a third courtyard, only partially excavated, seems to have been devoted to domestic use. The plan, with its large courtyards and narrow rooms, is very different from the contemporary one or two-roomed structures inside the walls, probably inhabited by the Berbers of the Awraba tribe. It is dated by coins and pottery to the reign of Idris I, and has been identified as his headquarters.[26]

Footnotes

- ↑ "Rirha/Gilda". INSAP (in French). 17 June 2020.

- ↑ "Archaeological Site of Volubilis".

- ↑ "Archaeological Site of Volubilis". African World Heritage Fund. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ↑ Haddadou, Mohand Akli (2006). Dictionnaire des racines berbères communes (in French). Algeria: Haut Commissariat à l'Amazighité. ISBN 978-9961-789-98-8.

- 1 2 "Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, vŏlūbĭlis". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ↑ Kreeft, Peter; Tacelli, Ronald K. (2009-09-20). Handbook of Christian Apologetics. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-7544-3.

- ↑ Getting started on Classical Latin. The Open University. 2015-08-07. ISBN 978-1-4730-0108-4.

- ↑ "وليلي أو قصر فرعون". زمان (in Arabic). 2014-11-14. Archived from the original on 2020-06-10. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ↑ "Description of the Medieval city, from the Museum of Volubilis". 9 March 2022.

- 1 2 Publishers, Nagel (1977). Morocco. Nagel Publishers. ISBN 978-2-8263-0164-6.

- ↑ Carrasco 2000, p. 128.

- 1 2 3 4 Rogerson 2010, p. 236.

- ↑ Février, James Germain (1966). "Inscriptions puniques et néopuniques". Études d'Antiquités africaines. 1 (1): 88–89, Pl. II.

- ↑ Parker 2010, p. 491.

- ↑ Davies 2009, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 Davies 2009, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rogerson 2010, p. 237.

- ↑ Romer 1998, p. 131.

- ↑ Löhberg 2006, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Volubilis Project – History.

- 1 2 MacKendrick 2000, p. 312.

- ↑ Andreeva, Fedorchuk & Nosonovsky 2019.

- ↑ Fentress & Limane 2010, p. 107.

- ↑ Conant 2012, p. 294.

- ↑ Akerraz 1985.

- 1 2 Fentress & Limane 2010, p. 103–122.

- 1 2 3 Rogerson 2010, p. 238.

- ↑ Leo Africanus trad. A. Épaulard, I, p. 245

- ↑ Windus 1725, p. 86.

- ↑ Windus 1725, p. 86–9.

- ↑ Shabeeny & Jackson 1820, p. 120–1.

- ↑ Harris 1889, p. 69–70.

- 1 2 Raven 1993, p. xxxi.

- ↑ Wright 1991, p. 117.

- ↑ Dyson 2006, p. 173–4.

- ↑ Wharton 1920, p. 45.

- ↑ Wright 1997, p. 136.

- ↑ Wharton 1920, p. 158.

- ↑ Dean 2002, p. 39.

- ↑ Parker 2010, p. 494.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 UNESCO September 1997, p. 73.

- ↑ Gran-Aymerich 2006, p. 60.

- 1 2 UNESCO September 1997, p. 74.

- ↑ Reports on these excavations, as well as a detailed plan of the site, can be found at http://www.sitedevolubilis.org.

- ↑ UNESCO September 1997, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 UNESCO September 1997, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 4 MacKendrick 2000, p. 304.

- 1 2 Raven 1993, p. 116.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Volubilis Project – Map.

- 1 2 Davies 2009, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 Rogerson 2010, p. 239.

- 1 2 3 4 MacKendrick 2000, p. 305.

- 1 2 3 MacKendrick 2000, p. 311.

- 1 2 3 4 Rogerson 2010, p. 240.

- ↑ Raven 1993, p. xxxiii.

- 1 2 Grimal 1984, p. 292.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rogerson 2010, p. 241.

- ↑ Rogerson 2010, p. 244.

- ↑ Roller 2003, p. 153 fn. 181.

- ↑ MacKendrick 2000, p. 303.

- ↑ Davies 2009, p. 43.

- ↑ Volubilis Project – House of the Cavalier.

- ↑ Rogerson 2010, p. 242.

- 1 2 3 Rogerson 2010, p. 243.

- ↑ Rogerson 2010, pp. 243–4.

- ↑ MacKendrick 2000, p. 310-11.

Bibliography

- Akerraz, Aomar, ed. (1985). "Note sur l'enceinte tardive de Volubilis". Bulletin Archéologique du Comité des Travaux Historiques. pp. 429–436.

- Andreeva, Sofia; Fedorchuk, Artem; Nosonovsky, Michael (2019). "Revisiting Epigraphic Evidence of the Oldest Synagogue in Morocco in Volubilis". Arts. Vol. 8. p. 127.

- Carrasco, J. L. Escacena (2000). "Archaeological relationship between North Africa and Iberia". In Arnaiz-Villena, Antonio; Martínez-Laso, Jorge; Gómez-Casado, Eduardo (eds.). Prehistoric Iberia: Genetics, Anthropology, and Linguistics. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-306-46364-4.

- Conant, Jonathan (2012). Staying Roman: Conquest and Identity in Africa and the Mediterranean, 439–700. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19697-0.

- Davies, Ethel (2009). North Africa: The Roman Coast. Chalfont St Peter, Bucks: Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-287-3.

- Dean, Sharon L. (2002). Constance Fenimore and Edith Wharton: Perspectives On Landscape and Art. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-57233-194-5.

- Dyson, Stephen L. (2006). In Pursuit of Ancient Pasts. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11097-5.

- Gran-Aymerich, Eve (2006). "Jane Dieulafoy". In Cohen, Getzel M.; Joukowsky, Martha Sharp (eds.). Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists. London: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-03174-0.

- Fentress, Elizabeth; Limane, Hassan (2010). "Excavations in Medieval Settlements in Volubilis 2000-2004". Quadernos de Madinat Zahra. No. 7p.

- Fentress, Elizabeth; Limane, Hassan (2018). Volubilis après Rome. Fouilles 2000-2004. Brill.

- Grimal, Pierre (1984) [1954]. Roman Cities [Les villes romaines]. Translated by G. Michael Woloch. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-08934-4.

- Harris, Walter (1889). The Land of an African Sultan: Travels in Morocco. London: S. Low. OCLC 249376810.

- Löhberg, Bernd (2006). Das "Itinerarium provinciarum Antonini Augusti": Ein kaiserzeitliches Strassenverzeichnis des Römischen Reiches. Berlin: Frank & Timme GmbH. ISBN 978-3-86596-085-6.

- MacKendrick, Paul Lachlan (2000). The North African Stones Speak. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4942-2.

- Parker, Philip (2010). The Empire Stops Here: A Journey along the Frontiers of the Roman World. London: Random House. ISBN 978-0-224-07788-0.

- Raven, Susan (1993). Rome in Africa. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-08150-4.

- Rogerson, Barnaby (2010). Marrakesh, Fez and Rabat. London: Cadogan Guides. ISBN 978-1-86011-432-8.

- Roller, Duane W. (2003). The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene. New York: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-30596-9.

- Romer, Frank E. (1998). Pomponius Mela's Description of the World. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08452-4.

- Shabeeny, El Hage abd Salam; Jackson, James Grey (1820). An account of Timbuctoo and Housa. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown. OCLC 165576157.

- "UNESCO Advisory Body Evaluation" (PDF). UNESCO. September 1997. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- Windus, John (1725). A journey to Mequinez, the residence of the present emperor of Fez and Morocco. London: Jacob Tonson. OCLC 64409967.

- Wharton, Edith (1920). In Morocco. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. OCLC 359173.

- Wright, Gwendolyn (1991). The Politics of Design in French Colonial Urbanism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-90848-9.

- Wright, Sarah Bird (1997). Edith Wharton's Travel Writing: The Making of a Connoisseur. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-15842-2.

- "The History of Volubilis". Volubilis Project. 25 September 2003. Archived from the original on April 24, 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "The House of the Cavalier". Volubilis Project. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- "Map of Volubilis". Volubilis Project. Archived from the original on February 21, 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

External links

- The Volubilis Project

- Volubilis on the UNESCO Website

- Images of Volubilis in the Manar al-Athar digital heritage archive

%252C_Algeria_04966r.jpg.webp)