| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

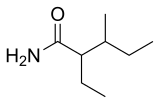

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Ethyl-3-methylpentanamide[1] | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.021.849 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | valnoctamide |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C8H17NO | |

| Molar mass | 143.230 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White crystals |

| log P | 1.885 |

| Pharmacology | |

| N05CM13 (WHO) | |

| |

| Pharmacokinetics: | |

| 94% | |

| Hepatic | |

| 10 hours | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H302 | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

760 mg kg−1 (oral, rat) |

| Related compounds | |

Related alkanamides |

Valpromide |

Related compounds |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Valnoctamide (INN, USAN) has been used in France as a sedative-hypnotic since 1964.[2] It is a structural isomer of valpromide, a valproic acid prodrug; unlike valpromide, however, valnoctamide is not transformed into its homologous acid, valnoctic acid, in vivo.[3]

Indications

In addition to being a sedative, valnoctamide has been investigated for use in epilepsy.[4][5][6]

It was studied for neuropathic pain in 2005 by Winkler et al., with good results: it had minimal effects on motor coordination and alertness at effective doses, and appeared to be equally effective as gabapentin.[7]

RH Belmaker, Yuly Bersudsky and Alex Mishory started a clinical trial of valnoctamide for prophylaxis of mania in lieu of the much more teratogenic valproic acid or its salts.[8]

Side effects

The side effects of valnoctamide are mostly minor and include somnolence and the slight motor impairments mentioned above.

Interactions

Valnoctamide is known to increase through inhibition of epoxide hydrolase the serum levels of carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide, the active metabolite of carbamazepine, sometimes to toxic levels.[9]

Chemistry

Valnoctamide is a racemic compound with four stereoisomers,[10] all of which were shown to be more effective than valproic acid in animal models of epilepsy and one of which [(2S,3S]-valnoctamide) was considered to be a good candidate by Isoherranen, et al. for an anticonvulsant in August 2003.[11]

Butabarbital can be hydrolyzed to Valnoctamide.[12]

References

- ↑ "valnoctamide - Compound Summary". PubChem Compound. USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information. 26 March 2005. Identification and Related Records. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ↑ Harl, F. M. (March 1964). "[Clinical Study Of Valnoctamide On 70 Neuropsychiatric Clinic Patients Undergoing Ambulatory Treatment]". La Presse Médicale (in French). 72: 753–754. PMID 14119722.

- ↑ Haj-Yehia, Abdullah; Meir Bialer (August 1989). "Structure-pharmacokinetic relationships in a series of valpromide derivatives with antiepileptic activity". Pharmaceutical Research. 6 (8): 683–689. doi:10.1023/A:1015934321764. PMID 2510141. S2CID 21531402.

- ↑ Mattos Nda, S. (May 1969). "[Use of Valnoctamide (nirvanil) in oligophrenic erethics and epileptics]". Hospital (Rio J) (in Portuguese). 75 (5): 1701–1704. PMID 5306499.

- ↑ Lindekens, H.; Ilse Smolders; Ghous M. Khan; Meir Bialer; Guy Ebinger; Yvette Michotte (November 2000). "In vivo study of the effect of valpromide and valnoctamide in the pilocarpine rat model of focal epilepsy". Pharmaceutical Research. 17 (11): 1408–1413. doi:10.1023/A:1007559208599. PMID 11205735. S2CID 24229165.

- ↑ Rogawski, MA (2006). "Diverse mechanisms of antiepileptic drugs in the development pipeline". Epilepsy Res. 69 (3): 273–294. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.02.004. PMC 1562526. PMID 16621450.

- ↑ Winkler, Ilan; Simcha Blotnik; Jakob Shimshoni; Boris Yagen; Marshall Devor; Meir Bialer (September 2005). "Efficacy of antiepileptic isomers of valproic acid and valpromide in a rat model of neuropathic pain". British Journal of Pharmacology. 146 (2): 198–208. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706310. PMC 1576263. PMID 15997234.

- ↑ RH Belmaker; Yuly Bersudsky; Alex Mishory; Beersheva Mental Health Center (2005). "Valnoctamide in Mania". ClinicalTrials.gov. United States National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 25 February 2006.

- ↑ Pisani, F; Fazio, A; Artesi, C; Oteri, G; Spina, E; Tomson, T; Perucca, E (1992). "Impairment of carbamazepine-10, 11-epoxide elimination by valnoctamide, a valpromide isomer, in healthy subjects". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 34 (1): 85–87. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1992.tb04114.x. PMC 1381382. PMID 1352988.

- ↑ Shimon Barel, Boris Yagen, Volker Schurig, Stephan Sobak, Francesco Pisani, Emilio Perucca and Meir Bialer. Stereoselective pharmacokinetic analysis of valnoctamide in healthy subjects and in patients with epilepsy. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 61, 442–449 (April 1997) doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90194-6

- ↑ Isoherranen, Nina; H. Steve White; Brian D. Klein; Michael Roeder; José H. Woodhead; Volker Schurig; Boris Yagen; Meir Bialer (August 2003). "Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships of (2S,3S)-valnoctamide and its stereoisomer (2R,3S)-valnoctamide in rodent models of epilepsy". Pharmaceutical Research. 20 (8): 1293–1301. doi:10.1023/A:1025069519218. PMID 12948028. S2CID 20755032.

- ↑ Freifelder, Morris; Geiszler, Adolph O.; Stone, George R. (1961). "Hydrolysis of 5,5-Disubstituted Barbituric Acids". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 26 (1): 203–206. doi:10.1021/jo01060a048. ISSN 0022-3263.